Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(1):27-34

Patient information: See related handout on hip pain, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Hip pain is a common and disabling condition that affects patients of all ages. The differential diagnosis of hip pain is broad, presenting a diagnostic challenge. Patients often express that their hip pain is localized to one of three anatomic regions: the anterior hip and groin, the posterior hip and buttock, or the lateral hip. Anterior hip and groin pain is commonly associated with intra-articular pathology, such as osteoarthritis and hip labral tears. Posterior hip pain is associated with piriformis syndrome, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, lumbar radiculopathy, and less commonly ischiofemoral impingement and vascular claudication. Lateral hip pain occurs with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Clinical examination tests, although helpful, are not highly sensitive or specific for most diagnoses; however, a rational approach to the hip examination can be used. Radiography should be performed if acute fracture, dislocations, or stress fractures are suspected. Initial plain radiography of the hip should include an anteroposterior view of the pelvis and frog-leg lateral view of the symptomatic hip. Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed if the history and plain radiograph results are not diagnostic. Magnetic resonance imaging is valuable for the detection of occult traumatic fractures, stress fractures, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Magnetic resonance arthrography is the diagnostic test of choice for labral tears.

Hip pain is a common presentation in primary care and can affect patients of all ages. In one study, 14.3% of adults 60 years and older reported significant hip pain on most days over the previous six weeks.1 Hip pain often presents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. The differential diagnosis of hip pain (eTable A) is broad, including both intra-articular and extra-articular pathology, and varies by age. A history and physical examination are essential to accurately diagnose the cause of hip pain.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Initial plain radiography of the hip should include an anteroposterior view of the pelvis and a frog-leg lateral view of the symptomatic hip. | C | 4 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging should be used for detection of occult hip fractures, stress fractures, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. | C | 23, 30, 33 |

| Magnetic resonance arthrography is the diagnostic test of choice for labral tears. | C | 6, 19 |

| Ultrasonography is a helpful diagnostic modality for patients with suspected bursitis, joint effusion, or functional causes of hip pain (e.g., snapping hip), and can be employed for therapeutic imaging-guided injections and aspirations around the hip. | C | 8, 9 |

| Diagnosis | Pain characteristics | History/risk factors | Examination findings | Additional testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior thigh pain | ||||

| Meralgia paresthetica | Paresthesia, hypesthesia | Obesity, pregnancy, tight pants or belt, conditions with increased intra-abdominal pressure | Anterior thigh hypesthesia, dysesthesia | None |

| Anterior groin pain | ||||

| Athletic pubalgia (sports hernia) | Dull, diffuse pain radiating to inner thigh; pain with direct pressure, sneezing, sit-ups, kicking, Valsalva maneuver | Soccer, rugby, football, hockey players | No hernia, tenderness of the inguinal canal or pubic tubercle, adductor origin, pain with resisted sit-up or hip flexion | Radiography: No bony involvement |

| MRI: Can show tear or detachment of the rectus abdominis or adductor longus | ||||

| Anterolateral hip and groin pain (C sign) | ||||

| Femoral neck fracture/stress fracture | Deep, referred pain; pain with weight bearing | Females (especially with female athlete triad), endurance athletes, low aerobic fitness, steroid use, smokers | Painful ROM, pain on palpation of greater trochanter | Radiography: Cortical disruption |

| MRI: Early bony edema | ||||

| Femoroacetabular impingement | Deep, referred pain; pain with standing after prolonged sitting | Pain with getting in and out of a car | FADIR and FABER tests are sensitive | Radiography: Cam or pincer deformity, acetabular retroversion, coxa profunda |

| Hip labral tear | Dull or sharp, referred pain; pain with weight bearing | Mechanical symptoms, such as catching or painful clicking; history of hip dislocation | Trendelenburg or antalgic gait, loss of internal rotation, positive FADIR and FABER tests | MRI: Can show a labral tear |

| Magnetic resonance arthrography: offers added sensitivity and specificity | ||||

| Iliopsoas bursitis (internal snapping hip) | Deep, referred pain; intermittent catching, snapping, or popping | Ballet dancers, runners | Snap with FABER to extension, adduction, and internal rotation; reproduction of snapping with extension of hip from flexed position | Radiography: No bony involvement |

| MRI: Bursitis and edema of the iliotibial band | ||||

| Ultrasonography: Tendinopathy, bursitis, fluid around tendon | ||||

| Dynamic ultrasonography: Snapping of iliopsoas or iliotibial band over greater trochanter | ||||

| Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease | Deep, referred pain; pain with weight bearing | 2 to 12 years of age, male predominance | Antalgic gait, limited ROM or stiffness | Radiography: Early small femoral epiphysis, sclerosis and flattening of the femoral head |

| Loose bodies and chondral lesions | Deep, referred pain; painful clicking | Mechanical symptoms, history of hip dislocation or low-energy trauma, history of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease | Limited ROM, catching and grinding with provocative maneuvers, positive FADIR and FABER tests | Radiography: Can show ossified or osteochondral loose bodies |

| MRI: Can detect chondral and fibrous loose bodies | ||||

| Osteoarthritis of the hip | Deep, aching pain and stiffness; pain with weight bearing | Older than 50 years, pain with activity that is relieved with rest | Internal rotation < 15 degrees, flexion < 115 degrees | Radiography: Presence of osteophytes at the acetabular joint margin, asymmetrical joint-space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis and cyst formation |

| Osteonecrosis of the hip | Deep, referred pain; pain with weight bearing | Adults: Lupus, sickle cell disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, corticosteroid use, smoking, and alcohol use; insidious onset, but can be acute with history of trauma | Pain on ambulation, positive log roll test, gradual limitation of ROM | Radiography: Femoral head lucency and subchondral sclerosis, subchondral collapse (i.e., crescent sign), flattening of the femoral head |

| MRI: Bony edema, subchondral collapse | ||||

| Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | Deep, referred pain; pain with weight bearing | 11 to 14 years of age, overweight (80th to 100th percentile) | Antalgic gait with foot externally rotated on occasion, positive log roll and straight leg raise against resistance tests, pain with hip internal rotation relieved with external rotation | Radiography: Widened epiphysis early, slippage of femur under epiphysis later |

| Septic arthritis | Refusal to bear weight, pain with leg movement | Children: 3 to 8 years of age, fever, ill appearance Adults: Older than 80 years, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, recent joint surgery, hip or knee prostheses | Guarding against any ROM; pain with passive ROM | Hip aspiration guided by fluoroscopy, computed tomography, or ultrasonography; Gram stain and culture of joint aspirate |

| MRI: Useful for differentiating septic arthritis from transient synovitis | ||||

| Transient synovitis | Refusal to bear weight | Children: 3 to 8 years of age, sometimes fever and ill appearance | Pain with extremes of ROM | |

| Lateral pain | ||||

| External snapping hip* | Pain with direct pressure, radiation down lateral thigh, snapping or popping | All age groups, audible snap with ambulation | Positive Ober test, snap with Ober test, pain over greater trochanter | Radiography: No bony involvement |

| MRI: Bursitis and edema of the iliotibial band | ||||

| Ultrasonography: Tendinopathy, bursitis, fluid around tendon | ||||

| Greater trochanteric bursitis* | Pain with direct pressure, radiation down lateral thigh | Runners, middle-aged women | Pain over greater trochanter | Dynamic ultrasonography: Snapping of iliopsoas or iliotibial band over greater trochanter |

| Greater trochanteric pain syndrome | Pain with direct pressure, radiation down lateral thigh | Associated with knee osteoarthritis, increased body mass index, low back pain; female predominance | Proximal iliotibial band tenderness, Trendelenburg gait is sensitive and specific | |

| Posterolateral pain | ||||

| Gluteal muscle tear or avulsion* | Pain with direct pressure, radiation down lateral thigh and buttock | Middle-aged women | Weak hip abduction, pain with resisted external rotation, Trendelenburg gait is sensitive and specific | MRI: Gluteal muscle edema or tears |

| Iliac crest apophysis avulsion | Tenderness to direct palpation | History of direct trauma, skeletal immaturity (younger than 25 years) | Iliac crest tenderness and/or ecchymosis | Radiography: Apophysis widening, soft tissue swelling around iliac crest |

| Posterior pain | ||||

| Hamstring muscle strain or avulsion | Buttock pain, pain with direct pressure | Eccentric muscle contraction while hip flexed and leg extended Skeletal immaturity, eccentric muscle contraction (cutting, kicking, jumping) | Ischial tuberosity tenderness, ecchymosis, weakness to leg flexion, palpable gap in hamstring | Radiography: Avulsion or strain of hamstring attachment to ischium |

| Ischial apophysis avulsion | Buttock pain, pain with direct pressure | MRI: Hamstring edema and retraction | ||

| Ischiofemoral impingement | Buttock or back pain with posterior thigh radiation, sciatica symptoms | Groin and/or buttock pain that may radiate distally | None established | MRI: Soft tissue edema around quadratus femoris muscle |

| Piriformis syndrome | Buttock pain with posterior thigh radiation, sciatica symptoms | History of direct trauma to buttock or pain with sitting, weakness and numbness are rare compared with lumbar radicular symptoms | Positive log roll test, tenderness over the sciatic notch | MRI: Lumbar spine has no disk herniation, piriformis muscle atrophy or hypertrophy, edema surrounding the sciatic nerve |

| Sacroiliac joint dysfunction | Pain radiates to lumbar back, buttock, and groin | Female predominance, common in pregnancy, history of minor trauma | FABER test elicits posterior pain localized to the sacroiliac joint, sacroiliac joint line tenderness | Radiography: Possibly no findings, narrowing and sclerotic changes of the sacroiliac joint space |

Anatomy

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket synovial joint designed to allow multiaxial motion while transferring loads between the upper and lower body. The acetabular rim is lined by fibrocartilage (labrum), which adds depth and stability to the femoroacetabular joint. The articular surfaces are covered by hyaline cartilage that dissipates shear and compressive forces during load bearing and hip motion. The hip's major innervating nerves originate in the lumbosacral region, which can make it difficult to distinguish between primary hip pain and radicular lumbar pain.

The hip joint's wide range of motion is second only to that of the glenohumeral joint and is enabled by the large number of muscle groups that surround the hip. The flexor muscles include the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, pectineus, and sartorius muscles. The gluteus maximus and hamstring muscle groups allow for hip extension. Smaller muscles, such as gluteus medius and minimus, piriformis, obturator externus and internus, and quadratus femoris muscles, insert around the greater trochanter, allowing for abduction, adduction, and internal and external rotation.

In persons who are skeletally immature, there are several growth centers of the pelvis and femur where injuries can occur. Potential sites of apophyseal injury in the hip region include the ischium, anterior superior iliac spine, anterior inferior iliac spine, iliac crest, lesser trochanter, and greater trochanter. The apophysis of the superior iliac spine matures last and is susceptible to injury up to 25 years of age.2

Evaluation of Hip Pain

HISTORY

Age alone can narrow the differential diagnosis of hip pain. In prepubescent and adolescent patients, congenital malformations of the femoroacetabular joint, avulsion fractures, and apophyseal or epiphyseal injuries should be considered. In those who are skeletally mature, hip pain is often a result of musculotendinous strain, ligamentous sprain, contusion, or bursitis. In older adults, degenerative osteoarthritis and fractures should be considered first.

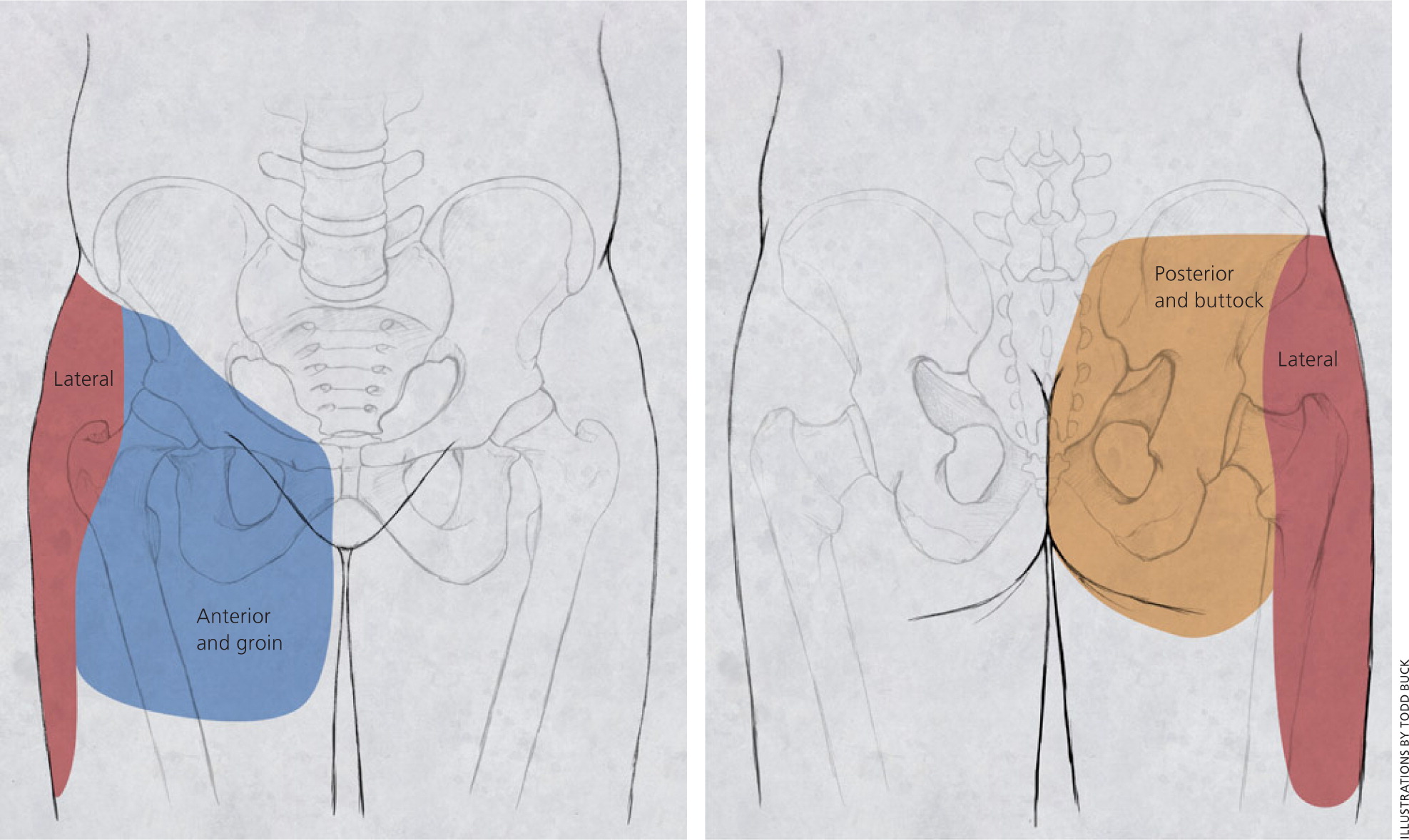

Patients with hip pain should be asked about antecedent trauma or inciting activity, factors that increase or decrease the pain, mechanism of injury, and time of onset. Questions related to hip function, such as the ease of getting in and out of a car, putting on shoes, running, walking, and going up and down stairs, can be helpful.3 Location of the pain is informative because hip pain often localizes to one of three basic anatomic regions: the anterior hip and groin, posterior hip and buttock, and lateral hip (eFigure A).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The hip examination should evaluate the hip, back, abdomen, and vascular and neurologic systems. It should start with a gait analysis and stance assessment (Figure 1), followed by evaluation of the patient in seated, supine, lateral, and prone positions (Figures 2 through 6, and eFigure B). Physical examination tests for the evaluation of hip pain are summarized in Table 1.

| Test | Other names | Positioning | Positive findings | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait testing (C sign, Figure 1A; gait analysis, Figure 1B) | — | Standing | Antalgic gait, Trendelenburg gait, pelvic wink (rotation of more than 40 degrees in the axial plane toward the affected hip when terminally extending the hip), excessive pronation or supination of the ankles, and limps caused by differing leg lengths | Hip labral tear, transient synovitis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, SCFE |

| Modified Trendelenburg test (Figure 1C) | Single leg stance phase | Standing | 2-cm drop in the level of the iliac crest, indicating weakness on the contralateral side | Hip labral tear, transient synovitis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, SCFE |

| ROM testing (Figure 2) | — | Supine, lateral, or sitting | Pain with passive ROM, limited ROM | Pain with passive ROM: Transient synovitis, septic arthritis |

| Limited ROM: Loose bodies, chondral lesions, osteoarthritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteonecrosis | ||||

| FABER test (Figure 3) | Patrick test | Supine | Posterior pain localized to the sacroiliac joint, lumbar spine, or posterior hip; groin pain with the test is sensitive for intra-articular pathology | Hip labral tear, loose bodies, chondral lesions, femoral acetabular impingement, osteoarthritis, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, iliopsoas bursitis |

| FADIR test (Figure 4) | Impingement test | Supine | Pain | Hip labral tear, loose bodies, chondral lesions, femoral acetabular impingement |

| Log roll test (Figure 5) | Passive supine rotation, Freiberg test | Supine | Restricted movement, pain | Piriformis syndrome, SCFE |

| Straight leg raise against resistance test (Figure 6) | Stinchfield test | Supine | Weakness to resistance, pain | Athletic pubalgia (sports hernia), SCFE, femoral acetabular impingement |

| Ober test (eFigure B) | Passive adduction | Lateral | Passive adduction past midline cannot be achieved | External snapping hip, greater trochanteric pain syndrome |

IMAGING

Radiography. Radiography of the hip should be performed if there is any suspicion of acute fracture, dislocation, or stress fracture. Initial plain radiography of the hip should include an anteroposterior view of the pelvis and a frog-leg lateral view of the symptomatic hip.4

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Arthrography. Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hip can detect many soft tissue abnormalities, and is the preferred imaging modality if plain radiography does not identify specific pathology in a patient with persistent pain.5 Conventional MRI has a sensitivity of 30% and an accuracy of 36% for diagnosing hip labral tears, whereas magnetic resonance arthrography provides added sensitivity of 90% and accuracy of 91% for the detection of labral tears.6,7

Ultrasonography. Ultrasonography is a useful technique for evaluating individual tendons, confirming suspected bursitis, and identifying joint effusions and functional causes of hip pain.8 Ultrasonography is especially useful for safely and accurately performing imaging-guided injections and aspirations around the hip.9 It is ideal for an experienced ultrasonographer to perform the diagnostic study; however, emerging evidence suggests that less experienced clinicians with appropriate training can make diagnoses with reliability similar to that of an experienced musculoskeletal ultrasonographer.10,11

Differential Diagnosis of Anterior Hip Pain

Anterior hip or groin pain suggests involvement of the hip joint itself. Patients often localize pain by cupping the anterolateral hip with the thumb and forefinger in the shape of a “C.” This is known as the C sign (Figure 1A).

OSTEOARTHRITIS

Osteoarthritis is the most likely diagnosis in older adults with limited motion and gradual onset of symptoms. Patients have a constant, deep, aching pain and stiffness that are worse with prolonged standing and weight bearing. Examination reveals decreased range of motion, and extremes of hip motion often cause pain. Plain radiographs demonstrate the presence of asymmetrical joint-space narrowing, osteophytosis, and subchondral sclerosis and cyst formation.12

FEMOROACETABULAR IMPINGEMENT

Patients with femoroacetabular impingement are often young and physically active. They describe insidious onset of pain that is worse with sitting, rising from a seat, getting in or out of a car, or leaning forward.13 The pain is located primarily in the groin with occasional radiation to the lateral hip and anterior thigh.14 The FABER test (flexion, abduction, external rotation; Figure 3) has a sensitivity of 96% to 99%. The FADIR test (flexion, adduction, internal rotation; Figure 4), log roll test (Figure 5), and straight leg raise against resistance test (Figure 6) are also effective, with sensitivities of 88%, 56%, and 30%, respectively.14,15 In addition to the anteroposterior and lateral radiograph views, a Dunn view should be obtained to help detect subtle lesions.16

HIP LABRAL TEAR

Hip labral tears cause dull or sharp groin pain, and one-half of patients with a labral tear have pain that radiates to the lateral hip, anterior thigh, and buttock. The pain usually has an insidious onset, but occasionally begins acutely after a traumatic event. About one-half of patients with this injury also have mechanical symptoms, such as catching or painful clicking with activity.17 The FADIR and FABER tests are effective for detecting intra-articular pathology (the sensitivity is 96% to 75% for the FADIR test and is 88% for the FABER test), although neither test has high specificity.14,15,18 Magnetic resonance arthrography is considered the diagnostic test of choice for labral tears.6,19 However, if a labral tear is not suspected, other less invasive imaging modalities, such as plain radiography and conventional MRI, should be used first to rule out other causes of hip and groin pain.

ILIOPSOAS BURSITIS (INTERNAL SNAPPING HIP)

OCCULT OR STRESS FRACTURE

Occult or stress fracture of the hip should be considered if trauma or repetitive weight-bearing exercise is involved, even if plain radiograph results are negative.21 Clinically, these injuries cause anterior hip or groin pain that is worse with activity.21 Pain may be present with extremes of motion, active straight leg raise, the log roll test, or hopping.22 MRI is useful for the detection of occult traumatic fractures and stress fractures not seen on plain radiographs.23

TRANSIENT SYNOVITIS AND SEPTIC ARTHRITIS

Acute onset of atraumatic anterior hip pain that results in impaired weight bearing should raise suspicion for transient synovitis and septic arthritis. Risk factors for septic arthritis in adults include age older than 80 years, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, recent joint surgery, and hip or knee prostheses.24 Fever, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein level should be used to evaluate the risk of septic arthritis.25,26 MRI is useful for differentiating septic arthritis from transient synovitis.27,28 However, hip aspiration using guided imaging such as fluoroscopy, computed tomography, or ultrasonography is recommended if a septic joint is suspected.29

OSTEONECROSIS

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease is an idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head in children two to 12 years of age, with a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.4 In adults, risk factors for osteonecrosis include systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, smoking, alcoholism, and corticosteroid use.30,31 Pain is the presenting symptom and is usually insidious. Range of motion is initially preserved but can become limited and painful as the disease progresses.32 MRI is valuable in the diagnosis and prognostication of osteonecrosis of the femoral head.30,33

Differential Diagnosis of Posterior Hip and Buttock Pain

PIRIFORMIS SYNDROME AND ISCHIOFEMORAL IMPINGEMENT

Piriformis syndrome causes buttock pain that is aggravated by sitting or walking, with or without ipsilateral radiation down the posterior thigh from sciatic nerve compression.34,35 Pain with the log roll test is the most sensitive test, but tenderness with palpation of the sciatic notch can help with the diagnosis.35

Unlike sciatica from disc herniation, piriformis syndrome and ischiofemoral impingement are exacerbated by active external hip rotation. MRI is useful for diagnosing these conditions.38

OTHER

Differential Diagnosis of Lateral Hip Pain

GREATER TROCHANTERIC PAIN SYNDROME

Lateral hip pain affects 10% to 25% of the general population.43 Greater trochanteric pain syndrome refers to pain over the greater trochanter. Several disorders of the lateral hip can lead to this type of pain, including iliotibial band thickening, bursitis, and tears of the gluteus medius and minimus muscle attachment.43–45 Patients may have mild morning stiffness and may be unable to sleep on the affected side. Gluteus minimus and medius injuries present with pain in the posterior lateral aspect of the hip as a result of partial or full-thickness tearing at the gluteal insertion. Most patients have an atraumatic, insidious onset of symptoms from repetitive use.43,45,46

Data Sources: We searched articles on hip pathology in American Family Physician, along with their references. We also searched the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence Reports, Clinical Evidence, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, and UpToDate. We performed a PubMed search using the keywords greater trochanteric pain syndrome, hip pain physical examination, imaging femoral hip stress fractures, imaging hip labral tear, imaging osteomyelitis, ischiofemoral impingement syndrome, meralgia paresthetica review, MRI arthrogram hip labrum, septic arthritis systematic review, and ultrasound hip pain. Search dates: March and April 2011, and August 15, 2013.