A more recent article on multiple sclerosis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(9):644-652

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common permanently disabling disorder of the central nervous system in young adults. Relapsing remitting MS is the most common type, and typical symptoms include sensory disturbances, Lhermitte sign, motor weakness, optic neuritis, impaired coordination, and fatigue. The course of disease is highly variable. The diagnosis is clinical and involves two neurologic deficits or objective attacks separated in time and space. Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in confirming the diagnosis and excluding mimics. Symptom exacerbations affect 85% of patients with MS. Corticosteroids are the treatment of choice for patients with acute, significant symptoms. Disease-modifying agents should be initiated early in the treatment of MS to forestall disease and preserve function. Two immunomodulatory agents (interferon beta and glatiramer) and five immunosuppressive agents (fingolimod, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, natalizumab, and mitoxantrone) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of MS, each with demonstrated effectiveness and unique adverse effect profiles. Symptom management constitutes a large part of care; neurogenic bladder and bowel, sexual dysfunction, pain, spasticity, and fatigue are best treated with a multidisciplinary approach to improve quality of life.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common permanently disabling disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) in young adults. The prevalence varies by geographic region, ranging from 110 cases per 100,000 persons in the northern United States to 47 per 100,000 in the southern United States.1 Women, smokers, and persons residing at higher latitudes or with a family history of MS are at increased risk of disease. Those with increased exposure to sunlight and higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are at decreased risk.2 Total costs associated with MS may exceed $50,000 per person annually.3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis requiring two neurologic deficits or objective attacks separated in time and space. | C | 13, 14 | If clinical criteria are not met, magnetic resonance imaging can be used to make the diagnosis. |

| Corticosteroids are the treatment of choice for patients with multiple sclerosis and significant, acute symptoms. | A | 18 | No significant difference has been found between parenteral and oral formulations. |

| The disease-modifying agents interferon beta, glatiramer (Copaxone), fingolimod (Gilenya), teriflunomide (Aubagio), and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) have been shown to decrease the frequency of exacerbations and progression of disease in patients with multiple sclerosis. | A | 20–24, 27, 28 | Each agent has a unique adverse effect profile making it more or less suitable for individual patients. |

Pathophysiology

The most common type of MS is relapsing remitting MS (Table 1).4–6 In the acute attack, T cells, B cells, and macrophages interact with adhesion molecules on blood vessel surfaces to traverse a blood-brain barrier weakened by matrix metalloproteinases. Once through, T cells and B cells release inflammatory mediators and immunoglobulins targeting the myelin sheath, while macrophages expose axonal surfaces and release harmful nitrous oxygen and oxygen free radicals. This cascade of events leads to demyelination and axonal injury.7

| Type | Disease course |

|---|---|

| Relapsing remitting (90% of cases) | Discrete attacks that evolve over days to weeks, followed by some degree of recovery over weeks to months; the patient has no worsening of neurologic function between attacks |

| Secondary progressive* | Initial relapsing remitting disease, followed by gradual neurologic deterioration not associated with acute attacks |

| Primary progressive and progressive relapsing (10% of cases) | Characterized by steady functional decline from disease onset; these types cannot be distinguished during early stages until attacks occur (progressive relapsing) or fail to occur (primary progressive); progressive relapsing is rarer than primary progressive |

Clinical Presentation

Typical symptoms of MS include sensory disturbances, motor weakness, optic neuritis (monocular visual impairment with pain), Lhermitte sign (electrical sensation down the spine on neck flexion), fatigue, and impaired coordination. Patients may also present with or develop pain, depression, sexual dysfunction, bladder urgency or retention, and bowel dysfunction8,9 (Table 28,10 ).

| Symptoms |

| Depressed mood |

| Dizziness or vertigo |

| Fatigue |

| Hearing loss and tinnitus |

| Heat sensitivity |

| Incoordination and gait disturbances |

| Pain |

| Sensory disturbances (dysesthesias, numbness, paresthesias) |

| Urinary symptoms |

| Visual disturbances (diplopia, oscillopsia) |

| Weakness |

| Signs |

| Ataxia |

| Decreased sensation (pain, vibration, position) |

| Decreased strength |

| Hyperreflexia, spasticity |

| Nystagmus |

| Visual defects (internuclear ophthalmoplegia, optic disc pallor, red color desaturation, reduced visual acuity) |

Differential Diagnosis

Multiple diseases may be confused with MS (Table 3).8–12 CNS pathologies to consider include other inflammatory, demyelinating, or degenerative diseases; infections; neoplasms; and migraines. Genetic diseases, nutritional deficiencies, and psychiatric diseases may also present in a manner similar to MS. The diagnosis of MS should be questioned in the presence of abrupt/transient symptoms, prominent cortical features (seizures, aphasia), peripheral neuropathy, and other organ (cardiac, hematologic) involvement, because these are not typical of MS.8–12

| Disease | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Central and peripheral nervous system disease | ||

| Degenerative disease | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease | |

| Demyelinating disease | Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | |

| Infection | Human immunodeficiency virus infection, Lyme disease, mycoplasma, syphilis | |

| Inflammatory disease | Behçet syndrome, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Structural disease | Arteriovenous malformation, herniated disk, neoplasm | |

| Vascular disease | Cerebrovascular accident, diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disease, migraine, vasculitis | |

| Genetic disorder | Leukodystrophy, mitochondrial disease | |

| Medication and illicit drug effects | Alcohol, cocaine, isoniazid, lithium, penicillin, phenytoin (Dilantin) | |

| Nutritional deficiency | Folate deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, vitamin E deficiency | |

| Psychiatric disease | Anxiety, conversion disorder, somatization | |

Diagnostic Criteria

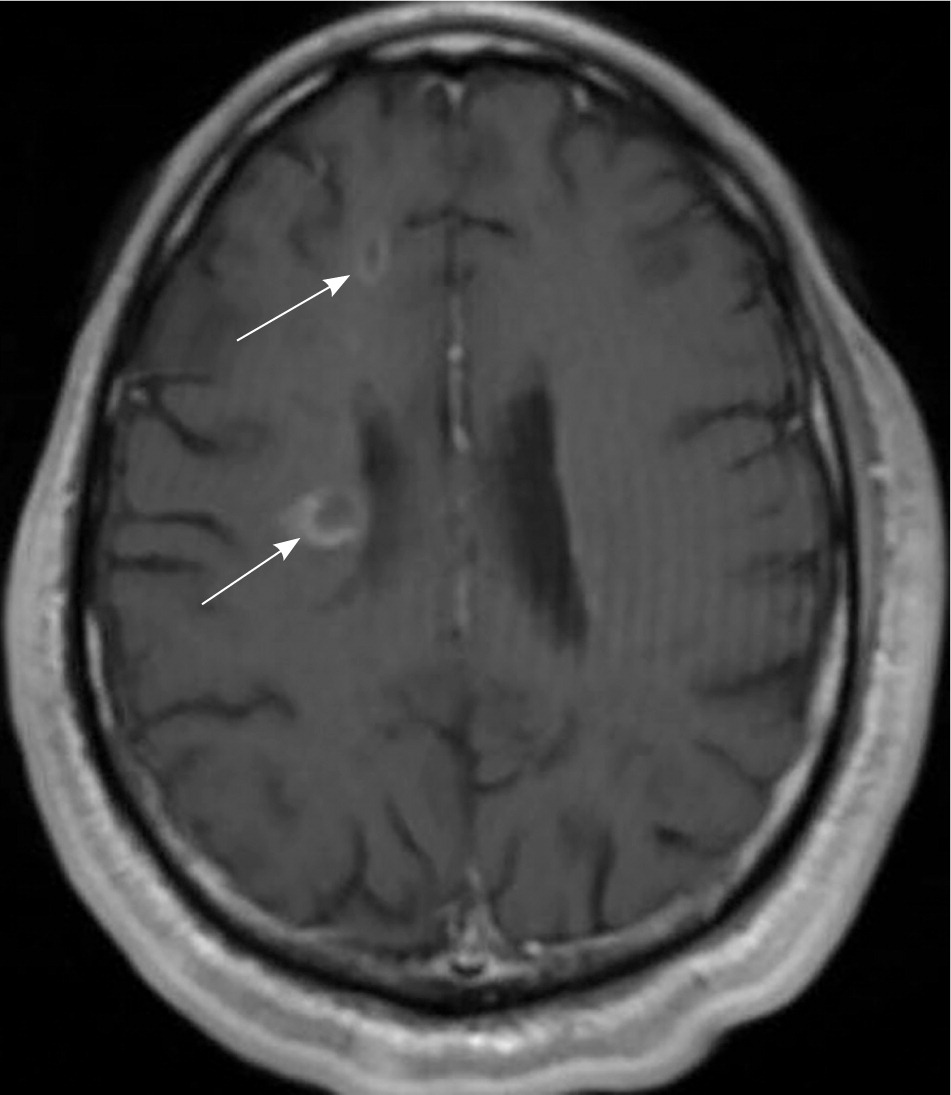

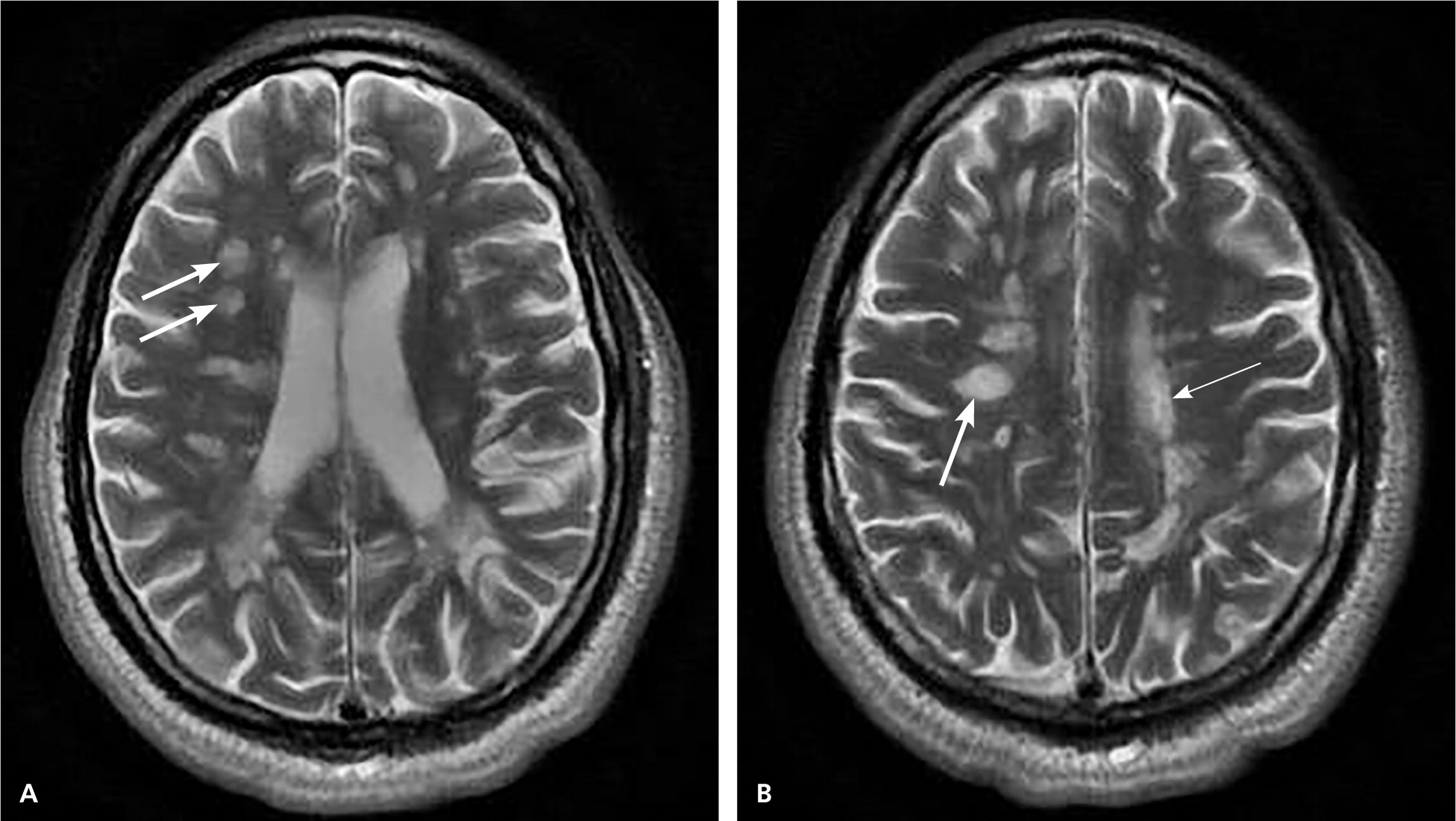

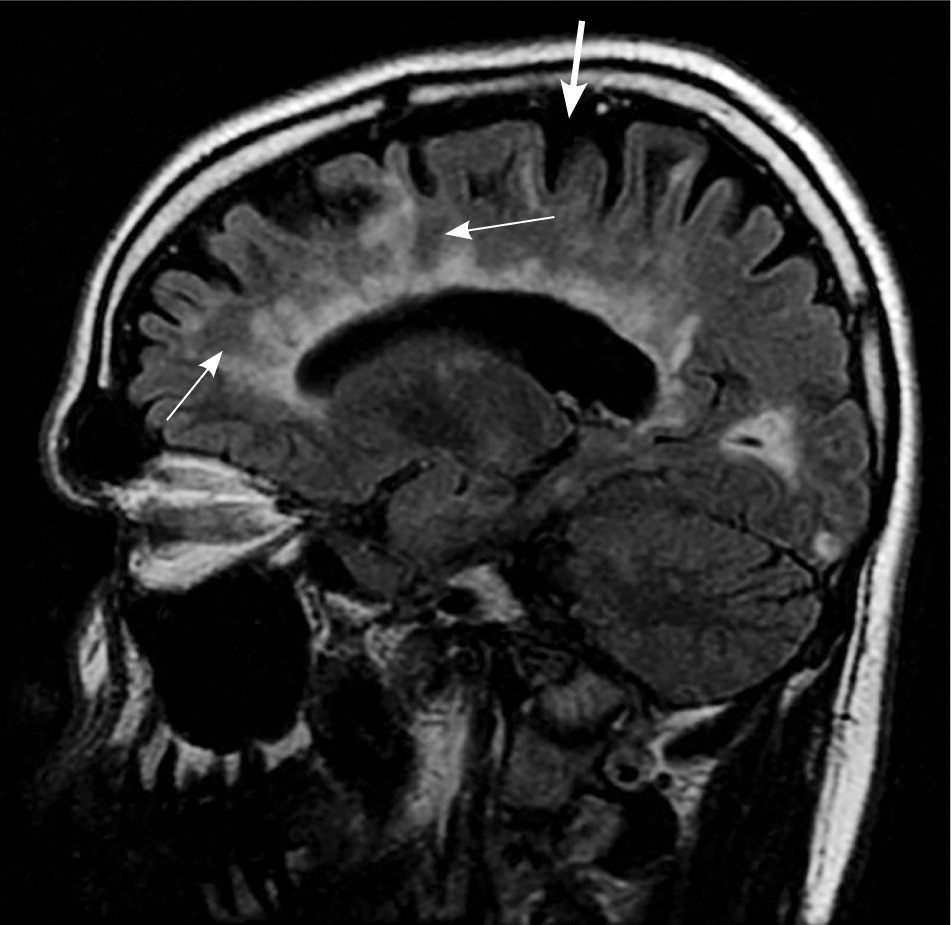

MS is a clinical diagnosis. Two neurologic deficits (e.g., focal weakness, sensory disturbances) separated in time and space, in the absence of fever, infection, or competing etiologies, are considered diagnostic.13,14 Attacks may be patient-reported or objectively observed, and must last for a minimum of 24 hours. Corroborating magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the diagnostic standard13 (Figure 1).

MRI is highly sensitive for CNS white matter lesions and can be used to diagnose MS in cases not meeting the threshold for clinical diagnosis13,14 (Figures 2 through 4; Table 413 ).However, other diseases (e.g., vasculopathies, leukoencephalopathy) also may present with white matter lesions that may initially be interpreted as consistent with MS.

| Clinical presentation | Additional data needed for MS diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 2 attacks*; objective clinical evidence of ≥ 2 lesions or objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion with reasonable historical evidence of a prior attack† | None‡ | ||

| ≥ 2 attacks*; objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion | Dissemination in space, demonstrated by: | ||

| ≥ 1 T2 lesion in at least 2 of 4 MS-typical regions of the CNS (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, or spinal cord)§; or | |||

| Await a further clinical attack* implicating a different CNS site | |||

| 1 attack*; objective clinical evidence of ≥ 2 lesions | Dissemination in time demonstrated by: | ||

| Simultaneous asymptomatic gadolinium-enhancing and nonenhancing lesions at any time; or | |||

| A new T2 and/or gadolinium-enhancing lesion(s) on follow-up MRI, irrespective of its timing with reference to a baseline scan; or | |||

| Await a second clinical attack* | |||

| 1 attack*; objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion (clinically isolated syndrome) | Dissemination in space and time, demonstrated by: | ||

| For DIS: | |||

| ≥ 1 T2 lesion in at least 2 of 4 MS-typical regions of the CNS (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, or spinal cord)§; or | |||

| Await a second clinical attack* implicating a different CNS site; and | |||

| For DIT: | |||

| Simultaneous presence of asymptomatic gadolinium-enhancing and nonenhancing lesions at any time; or | |||

| A new T2 and/or gadolinium-enhancing lesion(s) on follow-up MRI, irrespective of its timing with reference to a baseline scan; or | |||

| Await a second clinical attack* | |||

| Insidious neurological progression suggestive of MS (PPMS) | 1 year of disease progression (retrospectively or prospectively determined) plus 2 of 3 of the following criteria§: | ||

| 1. Evidence for DIS in the brain based on ≥ 1 T2 lesions in the MS-characteristic (periventricular, juxtacortical, or infratentorial) regions | |||

| 2. Evidence for DIS in the spinal cord based on ≥ 2 T2 lesions in the cord | |||

| 3. Positive CSF (isoelectric focusing evidence of oligoclonal bands and/or elevated IgG index) | |||

In addition to MRI, evoked potentials (visual, auditory, and somatosensory) may provide objective evidence of deficits consistent with MS. Visual evoked potentials are especially helpful for persons with vision-related symptoms.8,13 Cerebrospinal fluid may be obtained, although this is not routinely recommended; analysis typically demonstrates oligoclonal bands and an increased immunoglobulin G concentration. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis is more useful in ruling out MS mimics and in diagnosing primary progressive MS than in diagnosing relapsing remitting MS.13 Serologic testing is performed to exclude other diseases (Table 5).8,11

| Test | Conditions that may mimic multiple sclerosis |

|---|---|

| Performed routinely | |

| Antinuclear antibody titers | Rheumatologic disease, systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Borrelia titers | Lyme disease |

| Complete blood count | Infection, inflammation, neoplasm |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Infection, inflammation |

| Rapid plasma reagin | Syphilis |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone level | Hypothyroidism |

| Vitamin B12 level | Vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Performed when appropriate to the clinical situation | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme level | Sarcoidosis |

| Autoantibody assays* (e.g., antineutrophil cytoplasmic, anticardiolipin, antiphospholipid, anti–SS-A, and anti–SS-B antibodies) | Behçet syndrome, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis |

| Human immunodeficiency virus screening | Human immunodeficiency virus infection |

| Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I screening | Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I |

| Very long chain fatty acid levels | Adrenoleukodystrophy |

Exacerbations

Exacerbations affect 85% of patients with MS12; infections and stress may play a role. For those with significant, acute symptoms, corticosteroids are the treatment of choice and have strong evidence of benefit.15 Although parenteral steroids build up to peak concentrations faster than oral preparations, a Cochrane review indicates no difference in effectiveness (as measured by clinical or radiologic markers) or safety between oral and parenteral preparations.16–18 If the disease is unresponsive to steroids, plasmapheresis may be performed. Plasma exchanges are relatively well tolerated and are usually performed every other day for 14 days.16

Disease-Modifying Agents

The goal of disease-modifying therapy is to forestall disease, preserve function, and sustain healthy immune function while suppressing the T-cell autoimmune cascade thought to be responsible for demyelination and axonal damage. Early treatment at or before the diagnosis of clinically confirmed MS may delay damage to the CNS.19 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved seven agents for the treatment of MS: interferon beta, glatiramer (Copaxone), fingolimod (Gilenya), teriflunomide (Aubagio), dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), natalizumab (Tysabri), and mitoxantrone (Table 6).19–30 Because of the chronic nature and evolving treatment of MS, disease-modifying treatment is typically managed by a neurologist with expertise in prescribing these potentially toxic agents.

| Agent | Dosage | Cost (yearly)* | Evidence (95% confidence interval) | Adverse effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interferon beta | $62,000 to $67,000 | Decrease in relapses: RR = 0.80; (0.73 to 0.88)20 | Injection site reactions (e.g., edema, inflammation, pain); influenza-like symptoms; leukopenia; elevated liver enzyme levels; depression and suicidal thoughts (increased with preexisting depression, neutralizing antibodies) | ||

| Interferon beta-1a IM (Avonex) | Intramuscular, weekly | Decrease in progression: RR = 0.69; (0.55 to 0.87)20 | |||

| Interferon beta-1a SC (Rebif) | Subcutaneous, three times per week | ||||

| Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) | Subcutaneous, every other day | ||||

| Glatiramer (Copaxone) | Subcutaneous, daily | $70,000 | Decrease in relapses: MD = 0.51; (0.22 to 0.81)21 | Injection site reactions, facial flushing, chest tightness, palpitations | |

| Decrease in disability at two years: MD = 0.33; (0.08 to 0.58)21 | |||||

| Fingolimod (Gilenya) | Oral, daily | $67,000 | Annualized relapse rate vs. placebo: 0.18 vs. 0.4022 | Bradycardia (contraindicated in recent heart disease or arrhythmia); elevated liver enzyme levels | |

| Decrease in progression at two years: HR = 0.70; (0.55 to 0.87)22 | Melanoma, macular edema, herpes encephalitis (only occurs at higher doses) | ||||

| Teriflunomide (Aubagio) | Oral, daily | $63,000 | Annualized relapse rate vs. placebo: 0.37 vs. 0.5423 | Alopecia, diarrhea, nausea, decreased white blood cell count, elevated liver enzyme levels, peripheral neuropathy | |

| Decrease in progression: HR = 0.76; (0.51 to 0.97)23 | |||||

| Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) | Oral, daily | $68,000 | Annualized relapse rate vs. placebo: 0.17 vs. 0.3624 | Flushing, abdominal pain, lymphocytopenia, elevated liver enzyme levels | |

| Decrease in progression: HR = 0.62; (0.44 to 0.87)24 | |||||

| Natalizumab (Tysabri) | Intravenous, once per month | $61,000 | Decrease in relapses: RR = 0.57; (0.47 to 0.69)25 | Infusion reactions, headache, fatigue, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | |

| Decrease in progression at two years: RR = 0.74; (0.62 to 0.89)25 | |||||

| Mitoxantrone | Intravenous, every three months | $900 | Decrease in relapses: MD = 0.85; (0.23 to 1.47)26 | Myelosuppression, elevated liver enzyme levels, decreased cardiac function, leukemia | |

| Decrease in progression: OR = 0.30; (0.09 to 0.99)26 | |||||

INTERFERON BETA

Interferon beta, an immunomodulatory agent with more than 20 years of safety data, is effective in decreasing exacerbations and the progression of relapsing remitting MS.20 Interferon beta is available in three injectable formulations. Common adverse effects include local reactions and influenza-like symptoms. Interferon treatment may be associated with suicidal thoughts, so other agents should be considered in patients with depression.28

GLATIRAMER

Glatiramer is an alternative immunomodulatory daily injection for relapsing remitting MS with a good safety record. Glatiramer decreases relapse and progression of disability at two years.21 Common adverse effects include local and systemic injection reactions (e.g., chest tightness, palpitations). Glatiramer should be avoided in persons with known hypersensitivity to this agent.28

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS

Fingolimod is the first oral agent that is FDA approved for disease modification in relapsing remitting MS. A study of 1,272 patients between 18 and 55 years of age with relapsing remitting MS compared fingolimod with placebo, and demonstrated a decrease in annual exacerbations and progression of disease at two years.22 Bradycardia is a known adverse effect; patients should be observed for six hours after taking their first dose, and the medication is contraindicated in those with recent heart disease or arrhythmia.22,28

The FDA has approved two additional oral agents. Teriflunomide, approved in September 2012, has been shown to decrease relapse rates compared with placebo. Adverse effects include elevated transaminase levels, alopecia, and diarrhea.23,27 Teriflunomide carries an FDA warning for hepatic toxicity. Dimethyl fumarate, approved in March 2013, has been shown to decrease relapses and disease progression. Adverse effects include flushing, abdominal pain, decreased lymphocyte counts, and elevated transaminase levels.24,28 All of these oral agents suppress the immune system and put patients at risk of opportunistic infections. Because of this, these agents are typically used when the disease does not respond to, or the patient is unable to tolerate, an immunomodulatory agent.

Natalizumab and mitoxantrone are immunosuppressive agents reserved for disease that does not respond to first-line agents. Although both are effective, natalizumab carries an FDA warning for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and mitoxantrone carries a warning for cardiotoxicity.25,26,29 Ongoing trials are evaluating the effectiveness and safety of additional agents in the treatment of MS to include the injectable daclizumab and oral cladribine and siponimod.31–33

Symptom-Specific Treatment and Multidisciplinary Care

Multidisciplinary treatment of primary and associated symptoms is essential in enhancing the quality of life in younger and older patients with MS.

NEUROGENIC BLADDER

More than 70% of patients with MS have urinary tract dysfunction, with 10% demonstrating urinary symptoms at initial diagnosis.34 Urinary dysfunction can be classified as failure to store or empty, and can be differentiated with postvoid residual testing.35 Failure-to-store symptoms are typically treated with anticholinergic medications, although patients should be cautioned about adverse effects, such as dry mouth and confusion. Nocturia may respond to limited evening fluid intake or intranasal desmopressin; if desmopressin is prescribed, patients should be cautioned about the potential for hyponatremia. Injectable onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) may be used if symptoms do not respond to these agents. Failure-to-empty symptoms are treated with clean intermittent catheterization, although some may respond to an alpha adrenergic blocker.10,34–36

NEUROGENIC BOWEL

Up to 75% of patients with MS experience constipation, incontinence, or both.37 Treatment should include dietary fiber, bulk-forming agents, and adequate hydration. Rectal stimulants, stool softeners, and enemas may be used if needed. Colostomy is an option for patients with intolerable symptoms.35,37

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

About 50% to 90% of men and 40% to 85% of women with MS have some type of sexual dysfunction.35 Although sexual dysfunction may have a considerable negative impact on quality of life, it is often unaddressed. Men are primarily treated with peripherally acting phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. There is no established pharmacologic agent for women. Collaboration with a sex therapist or couples counselor may be beneficial.35,38

PAIN

Trigeminal neuralgia and dysesthetic (neuropathic) limb pain are common. Trigeminal neuralgia is initially treated with carbamazepine (Tegretol) and baclofen (Lioresal), as it is in persons without MS. Neuropathic pain in MS may be treated with tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.35,39 Hydrotherapy has also been shown to be helpful in pain management, and is beneficial for the spasticity associated with MS.40 Cannabinoid therapy may be helpful for pain symptoms.41

SPASTICITY

Baclofen is a first-line agent and works by decreasing alpha motor neuron activity. Oral baclofen has a short half-life and is associated with daytime sedation and muscle weakness. Intrathecal baclofen can be used to avoid daytime sedation, although muscle weakness may still occur. Diazepam (Valium) and gabapentin (Neurontin) may be used alone or in conjunction with baclofen.10,35,38 OnabotulinumtoxinA, with or without concomitant physical therapy, may also be helpful.36 Although cannabinoid therapy has been used for spasticity, the evidence for its effectiveness is mixed. The American Academy of Neurology states that patients should be counseled that these agents are probably ineffective for objective spasticity.41

FATIGUE

More than 90% of patients with MS report fatigue; one-third report it to be their most troubling symptom, and many present with it.35 Although fatigue may occur as a result of comorbid depression, it also may appear independently. Fatigue has profound impacts on quality of life and is a leading cause of disability claims.35,38

Treatment for fatigue is multifocal. After evaluating for comorbid causes of fatigue (e.g., sleep disorders, thyroid disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia), environmental manipulation, such as controlling heat and humidity levels, may help prevent flare-ups. Energy conservation measures such as napping and the use of assistive devices for mobility may be recommended based on the individual patient. Amantadine has been used off label in a limited number of trials and has been found to be beneficial for fatigue, although it is associated with insomnia and confusion.43,44 Other medications, such as modafinil (Provigil), have been tried with mixed results, and are not FDA approved for patients with MS.45

Other Issues

CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT

The prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and other vascular comorbidities in patients with MS is similar to that in the general population. The presence of these conditions may worsen the course of MS. In addition to using targeted MS and symptom-modifying therapies, physicians should also manage these comorbidities.46

INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE

Surveys show that more than 50% of patients with MS seek treatments such as acupuncture, chiropractic manipulations, massage, yoga, and herbal therapies.47,48 Physicians should ask patients if they are using integrative treatments, and should be prepared to help them find quality information on the risks and benefits of the treatments they choose. Table 7 provides information and resources on traditional and integrative treatments for MS.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the keyword and medical subject heading multiple sclerosis. The search included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, clinical trials, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, and review articles. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Search dates: January 2012 through June 2014.