Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(2):106-112

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

The swollen red eyelid is a common presentation in primary care. An understanding of the anatomy of the orbital region can guide care. Factors that guide diagnosis and urgency of care include acute vs. subacute onset of symptoms, presence or absence of pain, identifiable mass within the eyelid vs. diffuse lid swelling, and identification of vision change or ophthalmoplegia. Superficial skin processes presenting with swollen red eyelid include vesicles of herpes zoster ophthalmicus; erythematous irritation of contact dermatitis; raised, dry plaques of atopic dermatitis; and skin changes of malignancies, such as basal or squamous cell carcinoma. A well-defined mass at the lid margin is often a hordeolum or stye. A mass within the midportion of the lid is commonly a chalazion. Preseptal and orbital cellulitis are important to identify, treat, and differentiate from each other. Orbital cellulitis is more often marked by changes in ability of extraocular movements and vision as opposed to preseptal cellulitis where these characteristics are classically normal. Less commonly, autoimmune processes of the orbit or ocular tumors with mass effect can create an initial impression of a swollen eyelid.

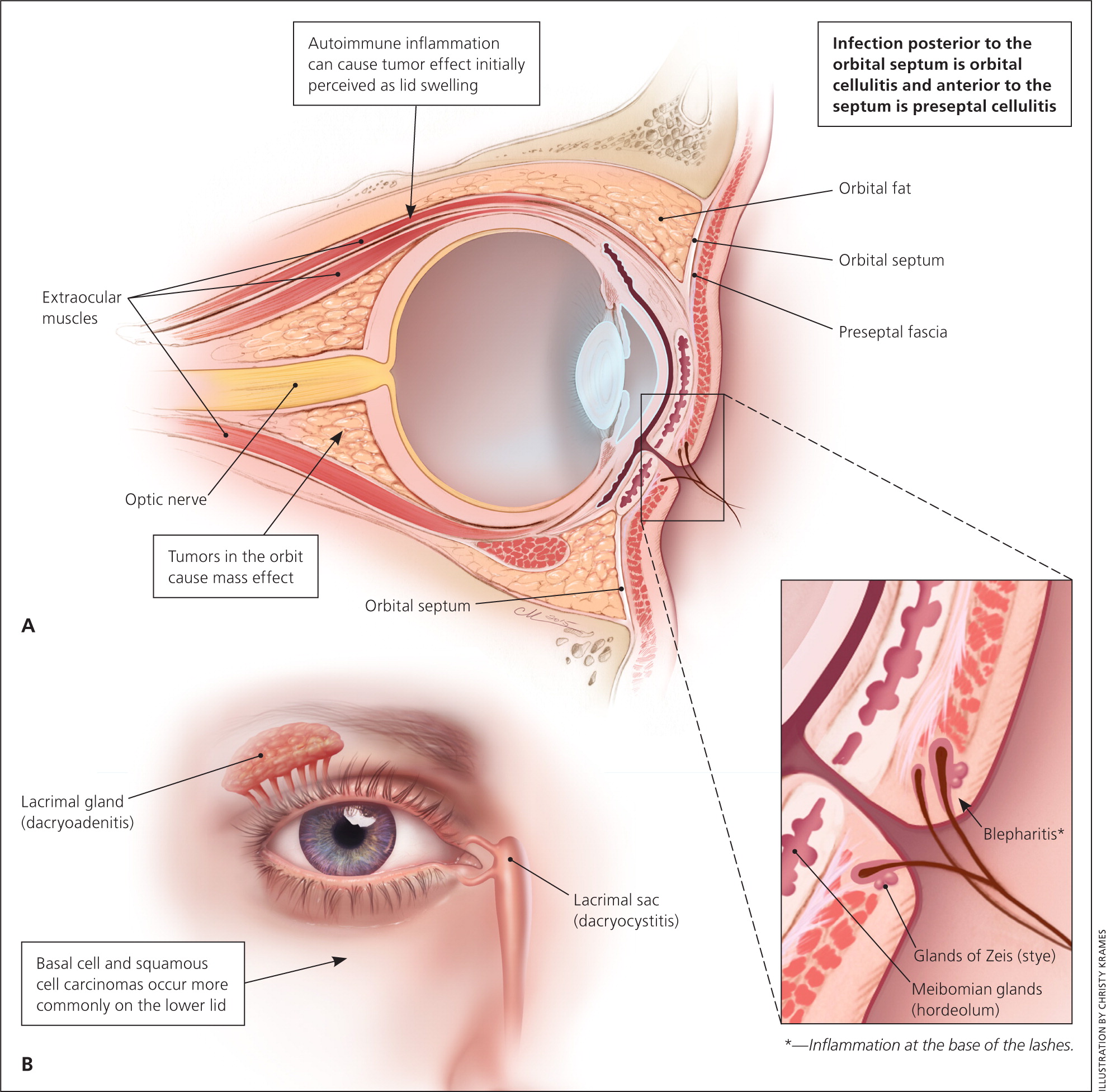

The eyelid contains multiple glandular structures and tissue connections that protect and contribute to function of the eye. Understanding the anatomy of the orbital region guides the awareness of pathology and diagnosis of conditions presenting with a swollen red eyelid (Table 1). Issues affecting the skin elsewhere on the body, such as atopic dermatitis, insect bites, cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis, can occur on the skin of the eyelid. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization and infections can also affect the eyelid. Systemic processes, such as autoimmune disease, metastatic cancer, heart failure, and nephrotic syndrome, can manifest in the orbital region.1–3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate imaging of the orbits and ophthalmology consultation are warranted for patients presenting acutely with vision changes, decreased extraocular movements, or penetrating trauma. | C | 1, 6, 8, 27, 31 |

| Patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus should be treated promptly with antiviral medication to avoid adverse outcomes to the cornea and to the patient's vision. | C | 12 |

| In patients with preseptal or orbital cellulitis, clinicians may consider empiric antibiotic coverage for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, depending on local bacterial prevalence. | C | 1 |

| Disease | Pathophysiology | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Superficial skin processes | ||

| Atopic dermatitis | Skin manifestation of systemic allergic sensitivity | Raised, dry plaque |

| Basal cell carcinoma | Neoplastic changes | Raised, umbilicated lesion with overlying telangiectasia |

| Capillary hemangioma | Localized growth of capillaries | Flat or raised well-circumscribed erythema; increases in size with crying |

| Contact dermatitis | Local reaction to irritative agent | Irritation, erythema, and edema |

| Herpes zoster ophthalmicus | Varicella zoster virus infection | Vesicles with surrounding erythema, possible bacterial superinfection; distributed unilaterally on forehead and upper eyelid in a dermatome |

| Periorbital ecchymosis (“black eye”) | Blunt trauma to orbit resulting in disruption of blood vessels | Ecchymosis increasing in size over 48 hours, then slowly improving |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Neoplastic changes | Painless erythematous flaky plaques, nodules, or ulcers |

| Inflammatory eyelid processes | ||

| Blepharitis | Inflammation of the base of the eyelashes and/or distal aspects of the eyelids; inflammation of the lacrimal gland | Irritated lid edges or eyelash |

| Chalazion | Noninfectious obstruction of meibomian tear gland | Discrete mass within the lid present for two or more weeks |

| Dacryoadenitis | Inflammation of the lacrimal gland | Circumscribed tender mass in upper outer lid; if advanced, may appear as the diffuse inflammation of preseptal cellulitis |

| Dacryocystitis | Inflammation of the lacrimal sac and duct | Tender mass at the medial aspect of the lower eyelid; if advanced, may appear as the diffuse inflammation of preseptal cellulitis |

| Hordeolum or stye | Hordeolum: infection of the meibomian (sebaceous) glands | Papule or furuncle at distal lid margin |

| Stye: infection of the sweat gland (gland of Zeis) of the eyelid | ||

| Local infections | ||

| Orbital cellulitis | Infection of the soft tissues within the orbit, posterior to the orbital septum, often due to spread from local sinus disease | Red, swollen, tender eyelid; extraocular movements limited because of pain or muscle edema; vision changes, diplopia; in children, fever and ill appearance |

| Preseptal cellulitis | Infection of lid tissues around the orbit, often with local skin defect | Red, swollen, tender eyelid; full extraocular movements; no vision changes |

| Mass effect from the orbit | ||

| Autoimmune orbital mass effect | Edema and inflammation of ocular muscles | Subacute onset bilateral proptosis, possible limited extraocular movements |

| Cavernous sinus thrombosis | Thrombosed superior ophthalmic vein and cerebral veins | Headache, vomiting, vision changes, stupor |

| Endophthalmitis | Inflammation of the globe, often caused by penetrating trauma | Vision loss |

| Orbital neoplasm | Tumor effect causing proptosis and affecting ocular muscle function and nerve function | Subacute onset, unilateral, painless proptosis |

Anatomy

The eyelid is a complex, fully functioning skin tissue that consists of eyelashes, lacrimal (tear) glands, sebaceous (oil or meibomian) glands, and sweat glands (glands of Zeis or Moll).4

Figure 1 depicts the anatomy of the orbit and eyelid. These structures can develop inflammatory reactions leading to a red, swollen eyelid. The lacrimal glands produce tears that run medially over the cornea and drain into the nasolacrimal sac.4 The eyelid and conjunctivae are colonized by the usual flora of the body, including fungi and S. aureus.4,5

The orbits contain the globe, muscles for eye movement, optic nerve, arteries, veins, and surrounding fat. The orbital septum creates an anatomic barrier of connective tissue that runs from the periosteum of the skull through the eyelid. The orbital septum separates preseptal tissues from the orbital tissues. Anatomically, the eyelid is part of the preseptal tissue. Tumor effect and inflammation posterior to the orbital septum can disrupt blood flow to the globe, impede function of the optic nerve, affect vision, and limit the function of ocular muscles.6,7

The paranasal sinuses (maxillary, frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid) abut the orbit on three sides.8 The lateral aspect of the ethmoid bone is called the lamina papyracea (Latin for “layer of paper”). It forms a thin, bony separation that can allow extravasation of inflammation from the ethmoid sinus into the orbital cavity.6,8,9

The eyelid can appear swollen because of processes in the eyelid or mass effects from the tissues posterior to the orbital septum. Prompt diagnosis is vital to guide appropriate therapy and avoid vision loss. Issues that warrant immediate ophthalmology consultation include penetrating trauma through the eyelid or into the globe, a change in vision such as diplopia, and loss of extraocular movements (ophthalmoplegia).1,6,8

Figure 2 depicts a suggested approach to evaluation of the swollen red eyelid.

Superficial Skin Processes

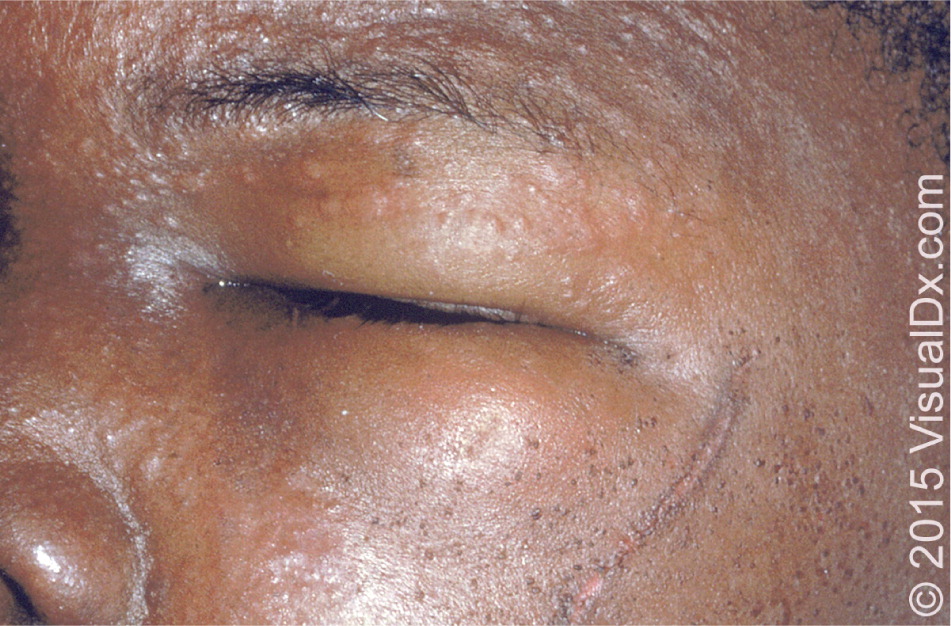

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is an infection with the varicella zoster virus. It most commonly affects the frontal nerve branch of the fifth cranial nerve. Like those found elsewhere on the body, herpes zoster lesions involve the dermal tissue, leading to erythematous macules, papules, and vesicles (Figure 3). Lesions are typically distributed on the forehead and upper eyelid, and do not cross the midline. Hutchinson sign is the presence of vesicles on the nose, and may indicate a higher risk of ocular involvement. Cutaneous complications include ptosis, lid scarring, entropion, ectropion, depigmentation, and necrosis.11 Recognition of herpes zoster ophthalmicus and treatment with antiviral therapy is important to prevent adverse effects on the cornea and vision.12

Periorbital ecchymosis (i.e., a “black eye”) and the myxedematous changes of systolic heart failure can manifest in the eyelids.1

Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma account for most malignant processes of the eyelid. They are more common on the lower eyelid.13,14 Basal cell carcinoma accounts for 80% to 95% of eyelid and medial canthus malignancies, whereas squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 5% to 10%.13,15 Malignant melanoma can also involve the eyelid.13 Other less common malignancies have been reported.13,16–18

Inflammatory Eyelid Processes

HORDEOLUM

A hordeolum, or stye, is a well-defined, often painful mass at the eyelid margin, commonly caused by bacterial infection of the follicle of the eyelash.14,21 A hordeolum is an infection of the internal meibomian (sebaceous) gland, whereas a stye (external hordeolum) is an infection of the external Zeis (sweat) gland.1,21,22 These localized masses appear as papules and furuncles located distally at the lid edge.1,21,22 They typically resolve spontaneously within a few days or weeks, and warm compresses can help.1,21 Chronic hordeola can lead to chalazia.22

CHALAZION

A chalazion is a noninfectious mass surrounding the meibomian gland within the midportion of the eyelid.1,14,22 Chalazia tend to present for longer than two weeks compared with the shorter natural history of sties or internal hordeola.1 Chalazia may develop from hordeola or when sebum clogs the gland.22 The skin of the lid appears unremarkable without findings such as a papule.1 The resultant erythema of the mass effect can be confused with cellulitis; however, chalazia are not painful.14,23 Surgical intervention with incision and drainage can be considered for very large chalazia.1,14,22 Intralesional steroid injections have also been used for treatment if conservative management with time and warm compresses is ineffective.24,25

BLEPHARITIS

Blepharitis is inflammation at the base of the eyelashes that can be chronic or acute, and is associated with dry eyes, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and Demodex mite infestation. Symptoms are often worse in the morning. Treatments include warm compresses, gentle massage, washes with diluted baby shampoo, topical antibiotics, topical steroids, oral antibiotics, and combinations of these therapies.26

DACRYOADENITIS

Dacryoadenitis is inflammation of the lacrimal glands, whereas dacryocystitis is inflammation of the lacrimal sac in the inferior lid.1 Both conditions can be caused by viruses or bacteria. Bacterial infections tend to be tenderer to palpation than viral infections.1 Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and gram-negative organisms are common pathogens. Clinically, these processes may mimic preseptal cellulitis.

Cellulitis

Preseptal (periorbital) and orbital cellulitis are infections of the soft tissues of the orbit. The orbital septum separates the preseptal and orbital spaces.6 Classically, local skin trauma allows infection of the preseptal tissues, whereas extravasation of a sinus infection is associated with infection posterior to the orbital septum.5,8,10,27 The ethmoid sinus and the wafer-thin lamina papyracea are often the sources of orbital cellulitis.8,9,27 Bacterial superinfection can occur over a viral process.28

The most common causes of these infections are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Haemophilus.6,29 Immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type b has substantially reduced the incidence of infection with Haemophilus.29 Preseptal and orbital cellulitis can present with edema around the orbit, fever, and the patient's report of eye pain.

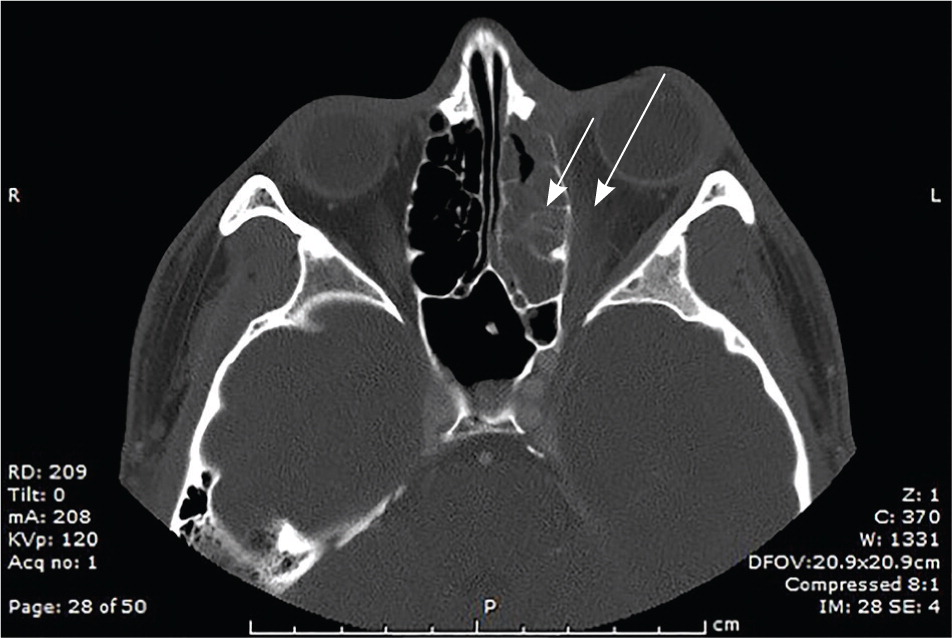

Computed tomography of the orbits with intravenous contrast media distinguishes preseptal from orbital cellulitis and can identify abscess formation.30 Imaging should be performed in patients with change in visual acuity, proptosis, decreased extraocular movement, or diplopia, or if there is an inability to examine the eye (e.g., the patient cannot open the lid).1,6,8,27,31 Computed tomography also demonstrates accompanying sinus disease that may warrant intervention (Figure 6).

Orbital cellulitis warrants consultation with an ophthalmologist and possibly an otolaryngologist, as well as inpatient therapy with intravenous antibiotics.8,9 Most cases of orbital cellulitis can be treated with a three-week course of systemic antibiotics.1,10,31 Surgical intervention may be required for patients with orbital abscesses or orbital cellulitis that does not respond to empiric antibiotic therapy.5 Preseptal cellulitis can be treated with an oral antibiotic that has anti–beta-lactamase activity (e.g., amoxicillin/clavulanate [Augmentin], cefpodoxime) on an outpatient basis if the lid and eye can be fully examined and if follow-up is assured.1

Because MRSA colonizes the skin and conjunctivae of a substantial percentage of persons,32 clinicians may consider empiric antibiotic coverage for MRSA depending on local bacterial prevalence.1 A lack of response to antibiotic therapy that does not cover MRSA should prompt consideration of MRSA infection.

A higher rate of periorbital infections has not been observed in patients with human immunodeficiency virus, but poor outcomes have been reported in patients with advanced AIDS secondary to opportunistic fungal and pseudomonal infections.33 Fungal and bacterial cultures should be obtained if there is concern of an opportunistic or atypical infection.

Orbital Mass Effect

Painless, slow onset of proptosis of the globe may initially be reported or identified as a swollen eyelid. Palpation of the lid can clarify whether it is edematous or whether there is a proptotic globe. Unilateral proptosis should trigger consideration of an orbital tumor. Bilateral proptosis should trigger consideration of inflammatory processes such as Graves disease (autoimmune thyroiditis).

Neoplasms, whether primary, metastatic, or lymphoma, can occur in the orbit. Ocular tumors such as retinoblastoma have a subacute onset and no inflammatory findings on imaging.1

Orbital pseudotumor is an idiopathic autoimmune inflammation of the orbit.34 It presents with lid swelling, erythema, eye pain, and ophthalmoplegia.1 Graves disease can present with painless, slow, insidious development of bilateral proptosis.34 Vision and extraocular movements remain intact until late in the disease process.34 Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis) has ocular muscle involvement in one-half of cases. Findings include bilateral proptosis, regional erythema, and painful or limited extraocular movements.34

Cavernous sinus thrombosis is a rare disease marked by a distended superior ophthalmic vein that is visible on imaging.30 Patients with cavernous sinus thrombosis tend to appear ill (e.g., headache, vomiting, vision changes, stupor).

Medication Effects

Medications such as glucocorticoids are known to cause periorbital cutaneous inflammation.13 Other drugs, including allopurinol, cephalosporins, corticosteroids, and valproic acid (Depakene), have reported associations with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, both of which lead to erythema, edema, and erosions of the eyelid.13 Dermatology and possible ophthalmology consultations are warranted for aggressive care of these conditions.

Data Sources: We searched PubMed using the terms cellulitis, eyelid, abscess, preseptal, and periorbital. Other sources included Essential Evidence Plus and searches of the journals Pediatrics, Archives of Ophthalmology, Ophthalmology, and Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. Selected references within relevant articles were also reviewed. Search dates: April 29, 2014, and August 29, 2014.

The authors thank CAPT John V. Hardaway, Chief of Ophthalmology Services at Tripler Army Medical Center, for review of the submitted manuscript; and Diane Kunichika, librarian at Tripler Army Medical Center, for assistance with the literature search.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.