Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(11):928-934

Patient information: See related handout on genital herpes, written by the author of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Genital herpes is a common sexually transmitted disease, affecting more than 400 million persons worldwide. It is caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) and characterized by lifelong infection and periodic reactivation. A visible outbreak consists of single or clustered vesicles on the genitalia, perineum, buttocks, upper thighs, or perianal areas that ulcerate before resolving. Symptoms of primary infection may include malaise, fever, or localized adenopathy. Subsequent outbreaks, caused by reactivation of latent virus, are usually milder. Asymptomatic shedding of transmissible virus is common. Although HSV-1 and HSV-2 are indistinguishable visually, they exhibit differences in behavior that may affect management. Patients with HSV-2 have a higher risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Polymerase chain reaction assay is the preferred method of confirming HSV infection in patients with active lesions. Treatment of primary and subsequent outbreaks with nucleoside analogues is well tolerated and reduces duration, severity, and frequency of recurrences. In patients with HSV who are HIV-negative, treatment reduces transmission of HSV to uninfected partners. During pregnancy, antiviral prophylaxis with acyclovir is recommended from 36 weeks of gestation until delivery in women with a history of genital herpes. Elective cesarean delivery should be performed in laboring patients with active lesions to reduce the risk of neonatal herpes.

Genital herpes is a common sexually transmitted disease caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) and characterized by lifelong infection and periodic reactivation. HSV, a DNA virus, is named from its protein coat as HSV-1 or HSV-2. HSV-1 is the chief cause of orolabial herpes. Until recently, genital herpes was more likely to be caused by HSV-2. However, the incidence of primary genital infection with HSV-1 is now as common or more common than HSV-2 in the United States.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Type-specific laboratory confirmation of HSV is recommended in patients with clinical disease to guide counseling and management. | C | 1, 24, 29 |

| Polymerase chain reaction assay is the preferred test for confirming HSV in clinically apparent lesions. | C | 24, 26, 27, 29 |

| Type-specific serologic testing should be offered to partners of patients with HSV infection to determine the risk of HSV acquisition. | C | 15, 24, 29 |

| Suppressive therapy reduces symptom severity, duration, and recurrence in patients with genital herpes. In HIV-negative patients, it is also effective in reducing transmission to at-risk partners. | A | 24, 32 |

| In persons with HIV and HSV-2 infections, suppressive therapy does not reduce the transmission of HSV-2 to at-risk partners. | B | 24, 36 |

Epidemiology

Worldwide, more than 400 million persons have genital herpes caused by HSV-2.2 In the United States, nearly one in five adults (approximately 50 million persons) has HSV-2 infection, with 1 million new infections occurring each year.3–5 Overall seroprevalence of HSV-1 is decreasing because of less childhood exposure to orolabial herpes; however, genital acquisition rates have increased simultaneously, with HSV-1 now representing at least one-half of new cases.1,6–8 This increase has been partly attributed to changing adolescent sexual practices involving more oral-genital contact.8,9

| Risk factor | Risk increase/prevalence | |

|---|---|---|

| Black, non-Hispanic | Three to four times the prevalence of non-Hispanic whites and Mexican-Americans | |

| Female sex | Twice the prevalence of males | |

| Hormonal contraception use, bacterial vaginosis, and vaginal group B streptococcus colonization | Each factor increases OR of shedding HSV-2: | |

| Hormonal contraception increases OR to 1.5 | ||

| Bacterial vaginosis increases OR to 2.0 | ||

| Group B streptococcus increases OR to 2.3 | ||

| Number of lifetime sex partners | Increase in HSV-2 infection prevalence: | |

| 1 partner: 2% to 5% | ||

| 2 to 4 partners: 7% to 19% | ||

| 5 to 9 partners: 10% to 22% | ||

| ≥ 10 partners: 19% to 37% | ||

| Oral-genital contact | Increases risk of transmitting HSV-1 from latent or active infection at oral site to genital site of uninfected partner | |

| Presence of other sexually transmitted diseases | Increases OR of shedding to 3.1 | |

Pathophysiology

Primary HSV infection results from a previously unexposed person having close contact with someone who is actively shedding the virus from skin or secretions. There may be a prodrome of hours to days consisting of pain, tingling, itching, or burning at the site of exposure. Epithelial damage at the portal of entry leads to eruption of vesicles that open, ulcerate, and reepithelialize during an outbreak that lasts about two weeks. During initial infection, viral DNA travels by axon to the spinal cord sensory ganglion where it persists for life.8 Reactivation of HSV causes migration back through the axon, its branches, or contralateral axons to the skin and mucosa.11

Clinical Manifestations

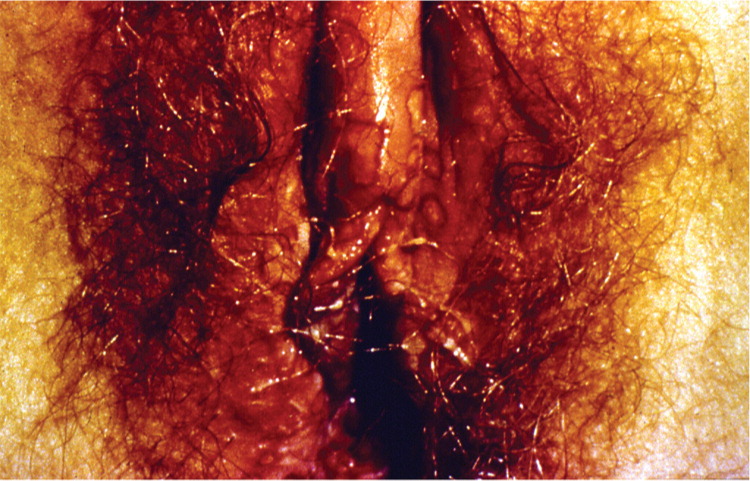

A visible outbreak consists of single or clustered vesicles on the genitalia (Figures 1 and 212 ), perineum, buttocks, upper thighs, or perianal areas that ulcerate before resolving. Primary infections may cause malaise, fever, or localized adenopathy. Subsequent outbreaks are usually milder and are caused by reactivation of latent virus.1,3 The classic presentation of HSV, whether primary infection or secondary outbreak, is absent most of the time, with many patients reporting minimal or no symptoms.8 Studies consistently report 65% to 90% of patients with genital HSV infection are unaware of its presence.1,3,13

Clinically apparent secondary outbreaks may have a prodrome anywhere along the involved axon, are milder, and usually heal within six to 12 days. Primary and secondary genital HSV-1 infections tend to be milder than HSV-2 infections. Patients with HSV-1 infection average zero to one recurrence per year, whereas HSV-2 recurs four to five times annually, with both types decreasing in recurrence over time. The wide variability in clinical expression may have greater significance to the individual's symptomatic course than the viral type.8

Asymptomatic viral shedding is common, occurring on 10% to 20% of all days and more often during the first year of infection, but continuing over the extended years studied.14–16 The frequency of subclinical infection and asymptomatic shedding facilitates HSV transmission. The first recognizable outbreak may not occur until well after the primary infection.1,17

Complications

| Acute urinary retention (particularly in women) |

| Aseptic meningitis (including a recurrent form) |

| Disseminated herpes |

| Encephalitis |

| Hepatitis |

| Neonatal infection |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Pneumonitis |

Diagnosis

Although herpes is the most common ulcerative genital disease in the United States, the coexistence of multiple etiologies must be considered. Table 3 lists the differential diagnosis.24,25 Because HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections are indistinguishable visually, suspected infection should be confirmed by type-specific testing to guide management.1,24 In the presence of active lesions, polymerase chain reaction assay is the preferred test, with sensitivity and specificity greater than 95%.24,26,27

| Infectious |

| Chancroid |

| Fungal infection |

| Genital herpes simplex |

| Granuloma inguinale |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum |

| Secondary bacterial infection |

| Syphilis |

| Noninfectious |

| Aphthous ulcers |

| Behçet syndrome |

| Fixed drug eruption |

| Neoplasms |

| Psoriasis |

| Sexual trauma |

Serologic testing may be useful if there is a history of suggestive symptoms but no lesions are present or polymerase chain reaction assay results are negative, or when the patient's partner is infected.24 Western blot is the diagnostic standard, although glycoprotein G tests are comparable (Table 4).28 Older immunoglobulin G and M antibody tests are not reliable and should not be used.28

| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| HerpeSelect 1 and 2 ELISA | 96 to 100 | 97 to 100 | Commercial |

| HerpeSelect 1 and 2 Immunoblot | 97 to 100 | 98 | Commercial |

| POCkit-HSV-2 | 93 to 100 | 94 to 97 | Point of care |

There is a window of two weeks to six months after HSV exposure to formation of detectable antibody, so repeat serologic testing may be needed to confirm recent acquisition. When the likelihood of infection is low, false-positive test results are more common. It is unclear how to counsel patients with a positive serologic test result but no history of genital herpes symptoms.29 Therefore, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend against serologic screening for genital herpes.24,30 Type-specific serologic testing should be offered to partners of patients with HSV infection to determine the risk of acquisition15,24,29 (Table 531 ).

| Patients with recurrent genital symptoms or atypical symptoms and negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction assay or culture |

| Patients with a clinical diagnosis of genital herpes but no laboratory confirmation |

| Patients who report having a partner with genital herpes |

| Patients presenting for a sexually transmitted disease evaluation (especially those with multiple sex partners) |

| Persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection |

| Men who have sex with men who are at increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus acquisition |

Interpretation of serology results is critical to accurately counsel patients. Serology confirms infection and the viral type. Because HSV-2 is almost always genitally acquired, the presence of HSV-2 antibody implies anogenital disease, even if there is no history of symptoms.24 However, the site of HSV-1 infection cannot be identified by positive HSV-1 serology results alone.5,24 HSV-1 antibody is present in 54% of the U.S. population, primarily acquired orolabially in childhood,5 and it is often asymptomatic whether orolabial or genital. Considering the increased incidence of new genital HSV-1 infections and changing sexual practices, clinicians should counsel patients who test positive for HSV-1 antibody that they may be able to transmit HSV to uninfected partners through oral or genital sex, and that they remain at risk of acquiring HSV-2 infection.8,24

Treatment and Prevention

Episodic and suppressive treatment of herpes is aimed at reducing the severity, duration, and recurrence of symptoms, and at preventing transmission to uninfected partners.24,32 Suppressive treatment may be intermittent or continuous. Three nucleoside analogues, which work by inhibiting viral DNA, are approved and well tolerated: acyclovir, famciclovir (Famvir), and valacyclovir (Valtrex). Regimens are identical for HSV-1 and HSV-2.

Nucleoside analogues are equally effective in treating first and subsequent episodes of HSV infection, in reducing the frequency and severity of recurrence, and in decreasing viral shedding.24,33–35 However, shedding is not completely eliminated with any treatment regimen, nor does treatment eliminate latent virus or affect transmission risk or symptoms once the medication is discontinued.24 Oral regimens32 recommended in the 2015 CDC guidelines are provided in Tables 6, 7, and 8.24

| Drug and dose | Frequency | Duration | Cost† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir, 400 mg | Three times per day | 5 days | $10 |

| Acyclovir, 800 mg | Twice per day | 5 days | $10 |

| Acyclovir, 800 mg | Three times per day | 2 days | $10 |

| Famciclovir (Famvir), 125 mg | Twice per day | 5 days | $30 ($115) |

| Famciclovir, 1 g | Twice per day | 1 day | $25 ($100) |

| Famciclovir, 500 mg and 250 mg | Single dose of 500 mg on day 1, followed by 250 mg twice per day on days 2 and 3 | 3 days | $20 ($75) |

| Valacyclovir (Valtrex), 500 mg | Twice per day | 3 days | $20 ($75) |

| Valacyclovir, 1 g | Once per day | 5 days | $30 ($100) |

Treatment should be based on the patient's disease profile, sexual practices, and psychosocial needs. Persons with infrequent or mild recurrences may opt for episodic treatment. Patient-initiated episodic treatment in those with known genital herpes is safe and effective, and avoids delay in initiating treatment.38 Chronic suppression is valuable for patients with frequent recurrences and for protecting at-risk partners. Drug resistance with long-term nucleoside analogue use is rare in immunocompetent persons.39 Topical acyclovir has minimal benefit for local symptom reduction, and does not improve episode duration, recurrence, or transmission rates.24,40

| Patients should be educated on the atypical and subtle signs of herpes outbreaks because it improves recognition. They should be advised to abstain from sex with uninfected partners when active lesions or prodromal symptoms are present. |

| Patients should be counseled to inform current sex partners about genital herpes and to inform future partners before initiating a sexual relationship. |

| Patients should be informed of the high incidence of asymptomatic viral shedding and the likelihood of transmitting HSV in the absence of an active outbreak. |

| Infection with HSV increases the risk of acquiring HIV infection. |

| In patients with HSV-2 and HIV infections, episodic or suppressive treatment is not effective in preventing HSV transmission to at-risk partners. |

| In HIV-negative persons with HSV infection, suppressive therapy and sexual abstinence during apparent outbreak and prodrome reduce the risk of HSV transmission. |

| Consistent use of male latex condoms reduces the risk of HSV transmission. |

| Asymptomatic partners of patients with HSV infection should be counseled on HSV and offered type-specific serologic testing. |

Considerations in Pregnancy

One in five pregnant women is seropositive for HSV-2, and more than 60% of pregnant women are positive for HSV-1.41 Yet, neonatal herpes is uncommon, occurring once in 3,200 live births. However, maternal primary infection with HSV-1 or HSV-2 at the time of delivery carries a 60% risk of neonatal herpes.

Antiviral prophylaxis with acyclovir is recommended from 36 weeks' gestation until delivery in women with a history of genital herpes to minimize active recurrence at the time of delivery.42 All three nucleoside analogues are U.S. Food and Drug Administration category B for breastfeeding and pregnancy. Elective cesarean delivery should be performed in laboring patients with active lesions to decrease the risk of HSV transmission.42

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the key terms genital herpes, diagnosis, testing, prognosis, treatment, clinical features, pregnancy, neonatal herpes, and vaccines. Also searched were the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, Clinical Key, Clinical Evidence, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website and selected issues of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report for 2015 STD treatment guidelines and epidemiologic data. Search dates: June 2015 through March 2016.