Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(3):172-179

Patient information: A handout on hemorrhoids is available.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Many Americans between 45 and 65 years of age experience hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoidal size, thrombosis, and location (i.e., proximal or distal to the dentate line) determine the extent of pain or discomfort. The history and physical examination must assess for risk factors and clinical signs indicating more concerning disease processes. Internal hemorrhoids are traditionally graded from I to IV based on the extent of prolapse. Other factors such as degree of discomfort, bleeding, comorbidities, and patient preference should help determine the order in which treatments are pursued. Medical management (e.g., stool softeners, topical over-the-counter preparations, topical nitroglycerine), dietary modifications (e.g., increased fiber and water intake), and behavioral therapies (sitz baths) are the mainstays of initial therapy. If these are unsuccessful, office-based treatment of grades I to III internal hemorrhoids with rubber band ligation is the preferred next step because it has a lower failure rate than infrared photocoagulation. Open or closed (conventional) excisional hemorrhoidectomy leads to greater surgical success rates but also incurs more pain and a prolonged recovery than office-based procedures; therefore, hemorrhoidectomy should be reserved for recurrent or higher-grade disease. Closed hemorrhoidectomy with diathermic or ultrasonic cutting devices may decrease bleeding and pain. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy elevates grade III or IV hemorrhoids to their normal anatomic position by removing a band of proximal mucosal tissue; however, this procedure has several potential postoperative complications. Hemorrhoidal artery ligation may be useful in grade II or III hemorrhoids because patients may experience less pain and recover more quickly. Excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids can greatly reduce pain if performed within the first two to three days of symptoms.

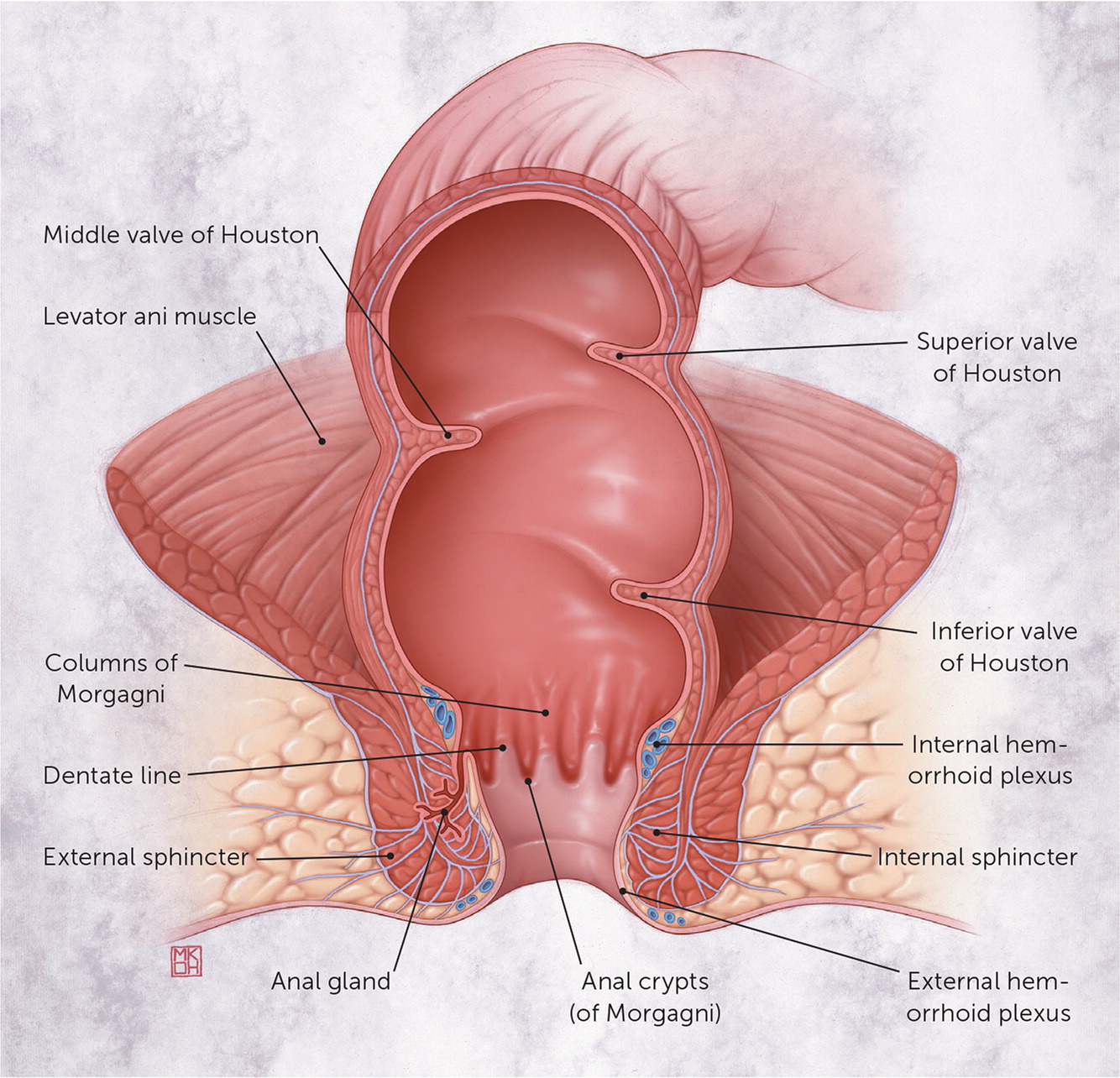

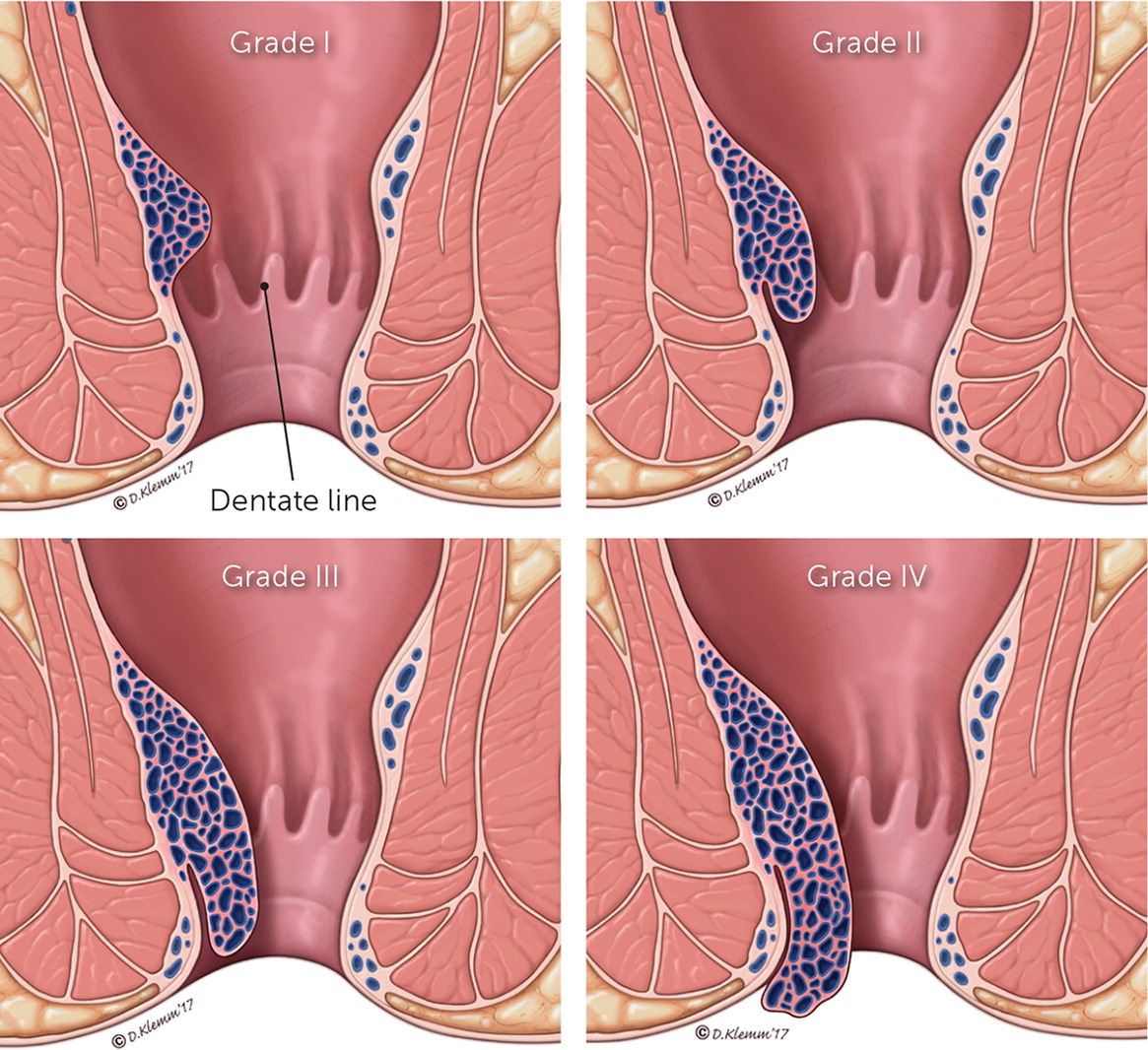

Hemorrhoids develop when the venous drainage of the anus is altered, causing the venous plexus and connecting tissue to dilate, creating an outgrowth of anal mucosa from the rectal wall. However, the exact pathophysiology is unknown. Hemorrhoids occur above or below the dentate line where the proximal columnar transitions to the distal squamous epithelium (Figure 11). The anus is approximately 4 cm long in adults, with the dentate line located roughly at the midpoint.2 Hemorrhoids developing above the dentate line are internal. They are painless because they are viscerally innervated. External hemorrhoids develop below the dentate line and can become painful when swollen. The extent of prolapse of internal hemorrhoids can be graded on a scale from I to IV, which guides effective treatment (Figure 2). This grading system is incomplete, however, because it focuses exclusively on the extent of prolapse and does not consider other clinical factors, such as size and number of hemorrhoids, amount of pain and bleeding, and patient comorbidities and preferences.3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing fiber intake is an effective first-line, nonsurgical treatment for hemorrhoids. | A | 7, 9–12 |

| Most patients who undergo excision of thrombosed hemorrhoids within two to three days of symptom onset achieve symptom relief. | B | 7, 10, 19–22 |

| Rubber band ligation is considered the preferred choice in the office-based treatment of grades I to III hemorrhoids because of effectiveness compared with other office-based procedures. | A | 7, 10, 21, 23, 37 |

| Excisional (conventional) hemorrhoidectomy is effective for the treatment of grade III or IV, recurrent, or highly symptomatic hemorrhoids. | A | 7, 9, 10, 21, 23, 32–35 |

| The use of Ligasure during conventional hemorrhoidectomy leads to decreased pain in the immediate postoperative period. | A | 32, 34 |

| Compared with conventional hemorrhoidectomy, stapled hemorrhoidopexy results in more frequent recurrence of symptoms and prolapse. | A | 10, 35–37 |

| Hemorrhoidal artery ligation is an emerging therapy with early outcomes similar to conventional hemorrhoidectomy for grade II or III hemorrhoids. | C | 28, 37 |

Epidemiology

Hemorrhoids are common. The exact prevalence is unknown because most patients are asymptomatic and do not seek care from a physician.4 A study of patients undergoing routine colorectal cancer screening found a 39% prevalence of hemorrhoids, with 55% of those patients reporting no symptoms.5 Hemorrhoids are more prevalent in persons 45 to 65 years of age.5,6 Although the precise cause is not well understood, hemorrhoids are associated with conditions that increase pressure in the hemorrhoidal venous plexus, such as straining during bowel movements secondary to constipation. Other associations include obesity, pregnancy, chronic diarrhea, anal intercourse, cirrhosis with ascites, pelvic floor dysfunction, and a low-fiber diet.6,7

Diagnosis

| Diagnosis | History | Physical examination |

|---|---|---|

| Abscess | Gradual onset of pain | Tender fluctuant mass |

| Cancer | Pain, bleeding, changes in bowel movements, weight loss | Ulcerating, indurated lesion |

| Condyloma | Possible bleeding; anal intercourse | Verrucous lesions |

| Fissure | Tearing pain with bowel movements | Visible tender fissure |

| Fistula | Soiling, itching | Visible opening of fistula |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, family history | Possible fistula; colitis on anoscopy |

| Polyps | Painless bleeding | Polyps on endoscopy |

| Proctalgia fugax | Painful rectum, no bleeding | Normal examination; diagnosis of exclusion |

| Proctitis | Painful rectum, bleeding | Tenderness on digital rectal examination |

| Rectal prolapse | Mass with Valsalva maneuver | Prolapse of rectal mucosa |

| Skin tags | History of hemorrhoids, no bleeding | Tags covered with normal skin |

HISTORY

Symptomatic internal hemorrhoids often present with painless bright red bleeding, prolapse, soiling, bothersome grape-like tissue prolapse, itching, or a combination of symptoms. The bleeding typically occurs with streaks of blood on stool and rarely causes anemia.8 External hemorrhoids may present similarly to internal hemorrhoids, with the exception that they can become painful, especially when thrombosed. Patients younger than 40 years with suspected hemorrhoidal bleeding do not require endoscopic evaluation if they do not have red flags (e.g., weight loss, abdominal pain, fever, signs of anemia), do not have a personal or family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and respond to medical management.6

Risk factors for colorectal cancer include a family history of colorectal cancer, adenomatous polyps, or inherited cancer syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis (including Gardner syndrome) or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome). Close follow-up is important in patients with rectal bleeding who do not undergo endoscopy because the incidence of colorectal cancer in younger adults is rising, with patients born in 1990 having twice the lifetime risk of a patient born in 1950.9 Patients older than 40 years with rectal bleeding and younger patients with risk factors should undergo full colon evaluation by colonoscopy, computed tomographic colonography, or barium enema, unless they have had a normal colon evaluation within the previous 10 years.6,10

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

In addition to an abdominal examination, the perineal and rectal areas should be inspected with the patient at rest and while bearing down.7,11 The patient can be in the lateral decubitus, lithotomy, or prone jackknife position (i.e., patient prone with table adjusted so that hips are flexed, with head and feet at a lower level). The presence of external hemorrhoids or prolapse of internal hemorrhoids may be obvious. A digital rectal examination can detect masses, tenderness, and fluctuance, but internal hemorrhoids are less likely to be palpable unless they are large or prolapsed.

Anoscopy is an effective way to visualize internal hemorrhoids that look like purplish bulges through the anoscope. Physicians should avoid use of clock face terms to describe lesions, because the position of the patient can vary. Instead, the physician should use terms relative to the patient, such as anterior, posterior, left, or right.7 Typically, hemorrhoids develop on anatomic planes, or hemorrhoidal columns, in the left lateral, right anterior, or right posterior aspect of the anus.

Medical Treatment

First-line conservative treatment of hemorrhoids consists of a high-fiber diet (25 to 35 g per day), fiber supplementation, increased water intake, warm water (sitz) baths, and stool softeners.7,11–13 Giving patients a chart with the fiber content of common foods may help them increase their fiber intake. One list is available at https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/high-fiber-foods/art-20050948. Fiber supplementation decreases bleeding of hemorrhoids by 50% and improves overall symptoms.12 Warm water baths decrease pain temporarily.13

There are multiple topical over-the-counter hemorrhoid remedies.11 These may provide temporary relief, but most have not been studied for effectiveness or safety for long-term use. Among these include astringents (witch hazel), protectants (zinc oxide), decongestants (phenylephrine), corticosteroids, and topical anesthetics. Over-the-counter hemorrhoid preparations often combine two or more of these ingredients. Supplements containing bioflavonoids (e.g., hidrosmin, diosmin, hesperidin, rutosides) are commonly used in other parts of the world for symptomatic relief of hemorrhoids.14 Although bioflavonoids may decrease bleeding, pruritus, and fecal leakage, as well as lead to overall symptom improvement, most studies are small and heterogeneous, and bioflavonoids are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for hemorrhoid treatment.14,15

Prescription therapies may also be part of first-line treatment. Topical nitroglycerin as a 0.4% ointment decreases rectal pain caused by thrombosed hemorrhoids, although it is more commonly used for anal fissures.16 Topical nifedipine also has been demonstrated to be effective for pain relief, but it must be compounded by a pharmacy because there is no commercially available preparation.17 A single injection of botulinum toxin into the anal sphincter effectively decreases the pain of thrombosed external hemorrhoids.18

Surgical Treatment

Office-based and surgical procedures can effectively treat hemorrhoids refractory to medical therapies. In general, the lower the grade, the more likely an office-based procedure will be successful, whereas recurring and grade III or IV hemorrhoids are more amenable to excisional hemorrhoidectomy.

OFFICE-BASED PROCEDURES

Thrombosed external hemorrhoids can be extremely painful. Although conservative management with topical therapies is reasonable, surgical removal of the thrombus within the first two to three days leads to quicker symptom resolution, lower risk of recurrence, and a prolonged recurrence interval.11,19–22 This procedure has been previously described in American Family Physician.22

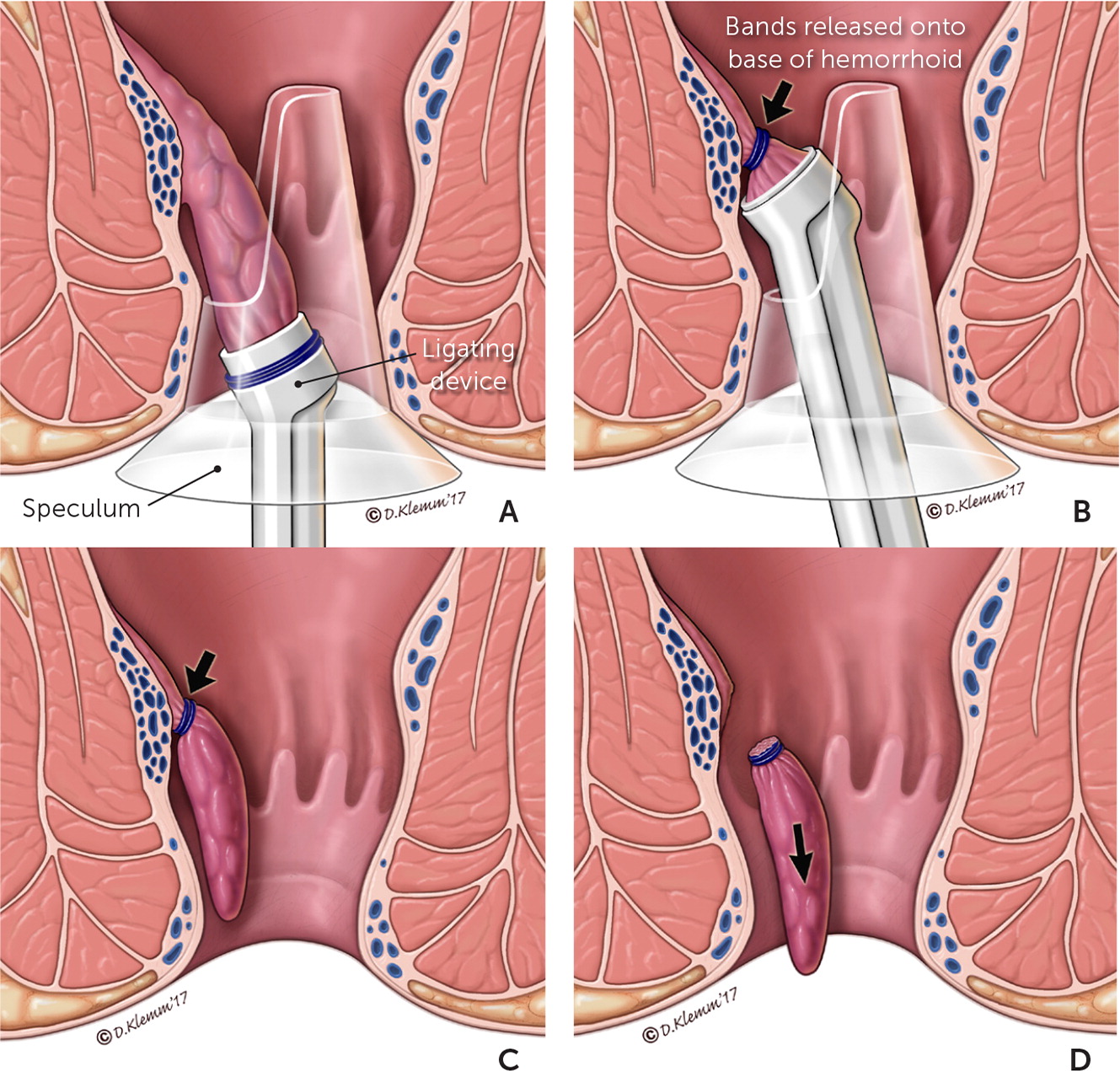

The primary office-based procedures to treat grade I to III internal hemorrhoids include banding and infrared photocoagulation. In rubber band ligation, a ligation instrument is inserted through a speculum to grasp or suction the targeted hemorrhoid to facilitate placement of a rubber band over the hemorrhoid down to its pedicle. The hemorrhoid ischemically necroses, and a virtual mucopexy occurs as the anal mucosa is pulled upward and the necrotic base puckers mucosa together, effectively elevating the more inferior anal mucosa7,10,21 (Figure 3). Infrared photocoagulation similarly stimulates necrosis to the proximal base of a hemorrhoid.7,10,11

When the two methods are compared, long-term success favors rubber band ligation, whereas pain improvement is greater with infrared photocoagulation.23 Photocoagulation is likely associated with less pain because there is no mucopexy during the procedure (i.e., pulling of the mucosal tissue and its somatic innervation upward from below the dentate line into the banding). Although rubber band ligation may be more painful historically, the differences in reported pain are smaller in more recent studies, and the failure rate is four times less than with photocoagulation.10,23 Recognizing specific characteristics of hemorrhoids (e.g., pedunculated clearly above the dentate line vs. broad-based and near the dentate line) facilitates decision making when considering which procedure to perform.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

The three goals of surgical hemorrhoidectomy are to remove the symptomatic hemorrhoidal columns, reduce the redundant tissue that accounts for the prolapsing hemorrhoidal tissues (mucopexy), and minimize pain and complications. Generally, the more definitive the excision, the greater the pain and the longer the recovery period without a significant reduction in possible complications.7,10,24,25 As noted with rubber band ligation, the reduction in postoperative pain is usually achieved by limiting the extent of the mucopexy portion of the procedure (Table 2).7,21,23–28

| Procedure | Resolution of symptoms | Reduction of prolapsing tissue (mucopexy) | Likelihood of recurrence | Amount of post-surgical pain | Longer recovery time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banding (i.e., rubber band ligation) | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + |

| Infrared photocoagulation | + | Not applicable | +++ | + | + |

| Open hemorrhoidectomy | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| Closed hemorrhoidectomy | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| Stapled hemorrhoidopexy | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Hemorrhoidal artery ligation (without mucopexy) | ++ | Not applicable | ++ | + | + |

| Hemorrhoidal artery ligation (with mucopexy) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Surgical excision is primarily accomplished through closed hemorrhoidectomy (mucosal defect typically closed; the most common technique in the United States) or open hemorrhoidectomy (removal of hemorrhoidal tissue with mucosal defect left open).29–31 These conventional techniques are the most effective for recurrent, highly symptomatic grade III or IV hemorrhoids. Compared with office-based procedures, conventional hemorrhoidectomy is more painful and associated with more blood loss and longer recovery time, but it has significantly lower rates of recurrence.7,23,26

Conventional hemorrhoidectomy has been modified to include two alternative energy devices, Ligasure and Harmonic Scalpel, which use diathermy and ultrasonic energy, respectively, to limit blood loss and postoperative pain as the instruments cut through tissue.32,33 A Cochrane review of 10 studies demonstrated significantly lower pain scores (using a validated visual analog scale) on postoperative day 1 in patients receiving Ligasure vs. conventional hemorrhoidectomy (weighted mean difference = −2.07; 95% confidence interval, −2.77 to −1.38).34 Additionally, the Ligasure procedure took less time to complete (11 trials; 9.15 minutes; 95% confidence interval, 3.21 to 15.09).34

An additional surgical procedure is the stapled hemorrhoidopexy.25 This is often referred to as stapled hemorrhoidectomy, which is a misnomer because the excised tissue is not the actual hemorrhoid, but rather loose proximal mucosa that has contributed to the prolapsed hemorrhoid. In this procedure, mucosal tissue 4 cm proximal to the dentate line is circumferentially removed and stapled so that the distal hemorrhoidal columns are effectively lifted back above the anal verge and attached to each other (mucopexy). A Cochrane review of 12 trials demonstrated that recurrent hemorrhoids were significantly more common after stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs. conventional excisional hemorrhoidectomy (odds ratio = 3.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.59 to 6.51).35 A 2007 meta-analysis showed no significant differences in complication rates between the two procedures, with the exception of increased rates of persistence or recurrence of hemorrhoids and prolapse at one year of follow-up in patients who had stapled hemorrhoidopexy.36 Additionally, patients undergoing stapled hemorrhoidopexy were noted to have small but significant benefits with less time to first bowel movement, shorter hospital stays, and fewer unhealed wounds at four weeks.36

Hemorrhoidal artery ligation, also known as transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization, is a promising emerging therapy for grade II or III hemorrhoids.28 In this procedure, the superficial artery directly proximal to the associated hemorrhoid is isolated and ligated. Specialized lighted anal speculums with or without Doppler probes and/or suture ports have been developed to assist with this technique. This can be performed with or without mucopexy. Early evidence suggests that hemorrhoidal artery ligation has similar outcomes to stapled hemorrhoidopexy with less postoperative pain.28,37 Hemorrhoidal artery ligation appears to have overall outcomes approaching those of conventional hemorrhoidectomy with similar postoperative pain.28,37

Postoperative pain has historically been universal with surgical hemorrhoidectomy. Pudendal and anal blocks with local anesthetics have greatly reduced the amount of post-hemorrhoidectomy pain.24 The use of a lateral internal sphincterotomy in conjunction with conventional hemorrhoidectomy has also demonstrated a reduction in postoperative pain.38

POSTPROCEDURAL CARE

Discerning postoperative complications (e.g., abscess, proctitis) from anticipated symptoms can be challenging. Pain and anal fullness are expected within the first week following hemorrhoidectomy or hemorrhoidopexy. Local medications are used to manage postoperative pain, with topical nitroglycerine ointment having the strongest evidence of effectiveness.39 Postoperative injection of botulinum toxin as well as oral or topical metronidazole (Flagyl; Metrogel) are also options, although their effectiveness is disputed.40–43

In addition to pain, common complications in the early postoperative period include bleeding, urinary retention, and thrombosed external hemorrhoids.37,44 Rare but potentially life-threatening complications that must be identified early include abscess, sepsis, massive bleeding, and peritonitis.37,45–47 Complications in the later postoperative period include recurrent hemorrhoids, anal stenosis, skin tags, late hemorrhage, constipation (often due to narcotic use), and fecal incontinence, all of which are often lesser than in the early postoperative period.37,47

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Mounsey, et al.11

Data Sources: The following evidence-based medicine resources were searched using the key words stapled hemorrhoidopexy, hemorrhoidectomy, hemorrhoids, hemorrhoid treatment, rubber band ligation hemorrhoids, hemorrhoid surgery, hemorrhoids pregnancy, and thrombosed external hemorrhoids: Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PubMed, UpToDate, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects. Search dates: June 2, 2016, and June 25, 2017.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.