A more recent article on diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(7):455-462

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most commonly diagnosed systemic inflammatory arthritis, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 1% worldwide. Women, smokers, and those with a family history of the disease are most often affected. Rheumatoid arthritis should be considered if there is at least one joint with definite swelling that is not better explained by another disease. In a patient with inflammatory arthritis, the presence of a rheumatoid factor and/or anti-citrullinated protein antibody, elevated C-reactive protein level, or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate is consistent with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis may impact organs other than the joints, including lungs, skin, and eyes. Rapid diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis allows for earlier treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, which is associated with better outcomes. The goal of therapy is to initiate early medical treatment to achieve disease remission or the lowest disease activity possible. Methotrexate is typically the first-line agent for rheumatoid arthritis. Additional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologic agents should be added if disease activity persists. Comorbid conditions, including hepatitis B or C or tuberculosis infections, must be considered when choosing medical treatments. Although rheumatoid arthritis is often a chronic disease, some patients can taper and discontinue medications and remain in long-term remission.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common autoimmune inflammatory arthritis, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 1% worldwide.1 It has a significant impact on occupational and daily activities, as well as mortality.2–4 This article reviews common questions on the diagnosis and management of RA, and presents evidence-based answers.

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC

The 2015 American College of Rheumatology guidelines continue to recommend methotrexate as the first-line treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, unless contraindications (e.g., frequent alcohol use, preexisting liver disease) are present.

In a randomized trial of patients who were on stable disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) regimens and in clinical remission for at least six months, 84% of patients who continued full DMARD treatment remained in remission after 12 months, compared with 61% who tapered DMARDs by 50%, and with 48% of those who stopped all DMARDs.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate should be the first-line disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with rheumatoid arthritis unless there are contraindications. | A | 16–18 |

| Patients with rheumatoid arthritis should be treated as early as possible to have the best chance of remission. | A | 19–25 |

| Patients should be screened for chronic infections, including latent tuberculosis, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus, before starting rheumatoid arthritis treatment. | C | 16, 27, 28 |

| Patients who are in remission from rheumatoid arthritis for more than six months and on stable medication regimens are candidates for tapering or discontinuing disease-modifying antirheumatic drug or biologic treatment. | B | 35, 36 |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not prescribe biologics for rheumatoid arthritis before a trial of methotrexate (or other conventional nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs). | American College of Rheumatology |

What Is the Typical Presentation of RA, and How Is It Diagnosed?

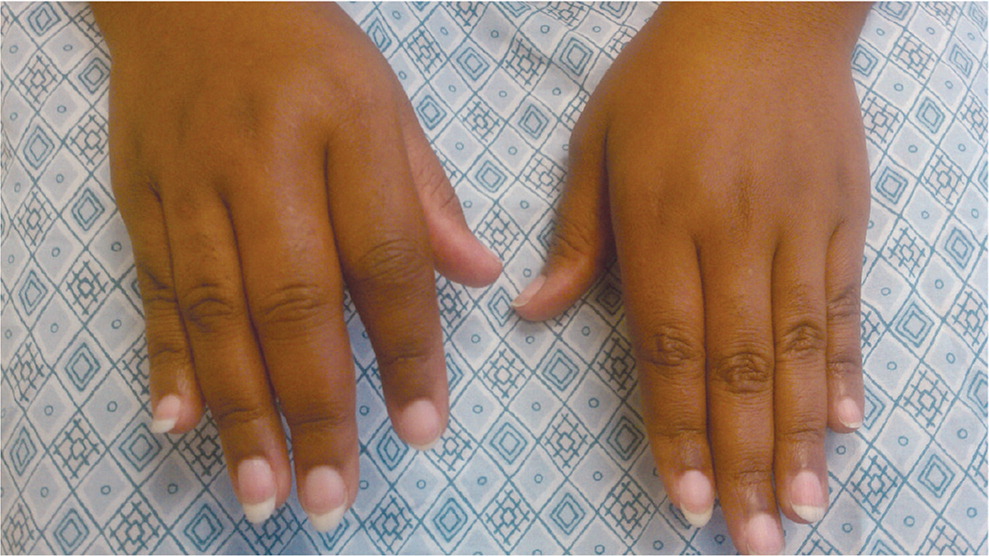

RA onset can occur at any age, but it peaks between 30 and 50 years of age. Women, smokers, and those with a family history of the disease are at higher risk. RA typically presents with pain and stiffness in multiple joints, most often the wrists, proximal interphalangeal joints, and metacarpophalangeal joints. The distal interphalanges and lumbar spine are not typically impacted by RA. Morning stiffness lasting more than one hour suggests an inflammatory etiology. Patients may also present with systemic symptoms of fatigue, weight loss, and anemia. Boggy swelling caused by synovitis may be visible (Figure 15 ), or subtle synovial thickening may be palpable on joint examination.

Physicians must use history and physical examination findings to differentiate the inflammatory arthritis in RA from another etiology, including systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, psoriatic arthritis, sarcoidosis, crystal arthropathy, and spondyloarthropathy. Radiography may be helpful in differentiation if the typical periarticular erosions of RA are present. The updated classification criteria for RA from the American College of Rheumatology (Table 16) no longer include the presence of rheumatoid nodules or radiographic erosive changes, both of which are less likely in early presentation. Positive serology (rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibody), as well as elevated inflammatory markers, may help confirm the diagnosis.

Target population (who should be tested): patients who

Classification criteria for RA (score-based algorithm: add score of categories A through D; a score ≥ 6 out of 10 is needed for classification of a patient as having definite RA)‡ | |

| Criteria | Score |

| A. Joint involvement§ | |

| One large joint|| | 0 |

| Two to 10 large joints | 1 |

| One to three small joints¶ (with or without involvement of large joints) | 2 |

| Four to 10 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints) | 3 |

| > 10 joints (at least one small joint)** | 5 |

| B. Serology (at least one test result is needed for classification)†† | |

| Negative RF and negative ACPA | 0 |

| Low-positive RF or low-positive ACPA | 2 |

| High-positive RF or high-positive ACPA | 3 |

| C. Acute phase reactants (at least one test result is needed for classification)‡‡ | |

| Normal CRP and normal ESR | 0 |

| Abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR | 1 |

| D. Duration of symptoms§§ | |

| < 6 weeks | 0 |

| ≥ 6 weeks | 1 |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Large multicenter prospective cohorts of patients with new-onset inflammatory arthritis have shown female predominance (77% of patients in cohort).7 The mean age at onset was 48 years, and patients had an average of seven swollen and eight tender joints.7 The C-reactive protein level was elevated in 39% of patients, 44% had elevated immunoglobulin M (IgM) rheumatoid factor, and 39% had anti-citrullinated protein antibody.7 An international cohort with early RA reported similar percentages of females, rheumatoid factor, and anti-citrullinated protein antibody positivity.8 Clinical trials including more patients with long-standing RA found higher rates of positive rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibody (close to 90%).9,10

What Are the Extra-Articular Manifestations of RA, and How Common Are They?

Extra-articular manifestations of RA include keratoconjunctivitis sicca, episcleritis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary nodules, rheumatoid nodules, and pleural effusions (Table 25). The prevalence of extra-articular manifestation varies from approximately 8% to 40%, depending on the patient population and how the manifestations are defined.

| Manifestation | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Cardiac | |

| Accelerated atherosclerosis | Leading cause of death in patients with RA |

| Pericarditis | Present in 30% to 50% of persons with RA on autopsy, rarely leads to tamponade |

| Eye | |

| Episcleritis/scleritis | Acute, red, painful eye; occurs in less than 1% of patients with RA |

| Keratoconjunctivitis sicca | Secondary Sjögren syndrome, dry mouth may also occur |

| Peripheral ulcerative keratitis | More severe scleritis, if untreated can perforate anterior chamber |

| Hematologic | |

| Amyloidosis | Caused by chronic inflammation |

| Felty syndrome | Splenomegaly, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia |

| Nervous system | |

| Cervical myelopathy | Caused by C1–C2 subluxation, seen on flexion-extension radiography |

| Neuropathy | Carpal tunnel, mononeuritis multiplex (foot drop) |

| Pulmonary | |

| Caplan syndrome | Nodules and pneumoconiosis (e.g., in coal miners) |

| Interstitial lung disease | May resemble bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, patient may also have pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| Pleural effusion | Exudative effusion with markedly low glucose level |

| Pulmonary nodules | Can be asymptomatic |

| Skin | |

| Rheumatoid nodules | Firm or rubbery, located on pressure areas (e.g., olecranon) |

| Vasculitis | Poor prognosis, increased mortality, rare but occurs with severe RA (i.e., erosive, deforming, and seropositive disease) |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The prevalence of extra-articular manifestations of RA varies widely in the literature, likely because of the different populations and definitions of extra-articular disease. A study cohort in Sweden noted severe extra-articular manifestations in 8% of patients, but these excluded more common extra-articular manifestations, such as rheumatoid nodules.11 A retrospective study of an RA cohort at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota included 609 patients with RA, 41% of whom had evidence of extra-articular manifestations, most commonly skin nodules and keratoconjunctivitis sicca.12 More recent studies on multiethnic populations with RA in Korea and California noted an extra-articular manifestation prevalence of 22%.13,14 Risk factors for developing extra-articular manifestations include male sex and seropositivity (rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibody, and antinuclear antibodies). A history of smoking is also strongly associated with the development of extra-articular manifestations, especially rheumatoid nodules (odds ratio = 7.3), vasculitis, and interstitial lung disease.15

What Are the First-Line Treatments for RA?

The American College of Rheumatology has updated guidelines on the treatment of RA and continues to recommend methotrexate as the first-line treatment, unless contraindications are present.16 Methotrexate may not be appropriate in patients with increased risk of hepatotoxicity, such as those with frequent alcohol use or with preexisting liver disease. Other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs;Table 35) can be considered for first-line treatment, including leflunomide (Arava), hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), and sulfasalazine (Azulfidine). If disease activity is high, glucocorticoids may also be added.16 Typically, 5 to 10 mg of prednisone daily for four to six weeks is sufficient, but the lowest possible dosage for the shortest possible duration should be used as a bridge until DMARD therapy is effective.

| Drug | Mechanism for rheumatoid arthritis | Adverse effects | Typical dosage | Cost* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonbiologic† | |||||

| Methotrexate | Inhibits dihydrofolate reductase | Liver effects, teratogenesis, hair loss, oral ulcers | Up to 25 mg orally or subcutaneously every week | $60 for 40 2.5-mg tablets $10 for one 2-mL vial (25 mg per mL) | |

| Leflunomide (Arava) | Inhibits pyrimidine synthesis | Liver effects, gastrointestinal effects, teratogenesis | 10 to 20 mg orally every week | $30 ($175) | |

| Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) | Antimalarial, blocks toll-like receptors | Rare ocular toxicity | 200 to 400 mg daily | $55 ($210) | |

| Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) | Folate depletion, other mechanisms unknown | Anemia in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, gastrointestinal effects | 500 to 1,500 mg twice per day | $15 ($90) | |

| Biologic | |||||

| Anti-TNF agents | |||||

| Adalimumab (Humira) | Anti-TNF-α | TB, opportunistic infection | 40 mg subcutaneously every two weeks | NA ($4,500) | |

| Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) | Anti-TNF-α, pegylated | TB, opportunistic infection | 400 mg subcutaneously every four weeks | NA ($4,000) | |

| Etanercept (Enbrel) | Anti-TNF-α, receptor | TB, opportunistic infection | 50 mg subcutaneously every week | NA ($4,500) | |

| Golimumab (Simponi) | Anti-TNF-α | TB, opportunistic infection | 100 mg every four weeks | NA ($4,900) | |

| Infliximab (Remicade) | Anti-TNF-α | TB, opportunistic infection, infusion reaction | 3 to 5 mg per kg intravenously every six to eight weeks | NA ($2,500) for two 100-mg vials | |

| Other biologic agents | |||||

| Abatacept (Orencia) | Costimulator blocker, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 | Opportunistic infection | 125 mg subcutaneously every week, or 500 to 1,000 mg intravenously every four weeks | NA ($4,000) | |

| Anakinra (Kineret) | Anti-interleukin-1 receptor blocker | Opportunistic infection, injection site pain | 100 mg subcutaneously daily | NA ($4,000) | |

| Rituximab (Rituxan) | Anti-CD20, eliminates B cells | Infusion reaction, opportunistic infection, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | 1,000 mg intravenously every six months | NA (> $5,000‡) | |

| Sarilumab (Kevzara) | Anti-interleukin-6 receptor blocker | Opportunistic infection | 150 to 200 mg subcutaneously every two weeks | NA ($2,700) | |

| Tocilizumab (Actemra) | Anti-interleukin-6 receptor blocker | Opportunistic infection, hyperlipidemia | 4 to 8 mg per kg intravenously every four weeks, or 162 mg subcutaneously every week or every two weeks | NA ($2,000) for one 20-mL vial (20 mg per mL) | |

| Tofacitinib (Xeljanz) | Janus kinase inhibitor | TB, opportunistic infection | 5 mg daily or twice per day, or 11 mg daily extended release | NA ($2,000) NA ($4,000) for extended release | |

Disease activity can be measured with a variety of validated scoring systems, including the Disease Activity Score (http://www.4s-dawn.com/DAS28/). More costly biologic drugs, which are engineered to block specific cytokines, are typically reserved for persons with refractory disease or who cannot tolerate nonbiologic DMARDs. Women of childbearing age should be counseled on medications that are known teratogens, such as methotrexate and leflunomide.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that in early RA, use of methotrexate with glucocorticoid taper led to remission after 16 weeks of therapy in nearly three-fourths of patients.17 This is a statistically similar rate of remission compared with patients who received combination therapy with methotrexate and either sulfasalazine or leflunomide, but with fewer adverse effects.17 Other clinical trials of patients with longer duration of RA have found less robust remission rates (closer to 40%) with methotrexate monotherapy.18 For patients who do not respond adequately to methotrexate monotherapy, the addition of DMARDs or biologics is indicated.16

How Do Early Intervention and Treat-to-Target Affect the Course of RA?

Longer duration of RA before initiating treatment is associated with a poorer prognosis. Patients who are treated early, typically within three months of symptom onset, have nearly twice the likelihood of achieving sustained remission.19 The goal of treatment is remission or the lowest disease activity possible. Medications are titrated as necessary to achieve this target, and frequent physician visits are required to monitor response to therapy.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 1995 randomized clinical trial of the gold-containing compound auranofin (Ridaura) noted that patients who received immediate treatment vs. an eight-month delay were better off after a five-year follow-up.20 A more recent observational study reported that patients who had RA with a median disease duration of three months before initial DMARD use achieved a lower disease activity score and less radiographic joint damage compared with patients being treated after a median disease duration of 12 months.21 Large cohorts have shown that patients who had symptoms less than 12 weeks before initiation of treatment were nearly twice as likely to achieve remission off medications (18.5%) than those with longer disease duration (10.5%).22 Early RA clinics at multiple centers in France and the Netherlands noted that at five-year follow-up, 5.4% to 11.5% of patients were in DMARD-free remission.23 These patients were started on treatment after a median of 18 to 21 weeks of symptoms. Ten-year follow-up of one clinical trial demonstrated that a strategy of treating to remission was effective in maintaining patients' function and limiting joint damage progression.24,25

How Do Comorbidities Impact the Management of RA?

Patients with RA may have other diseases and conditions that require consideration before initiating treatment for RA. The American College of Rheumatology recommends screening for latent tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infections before starting treatment.16 This is important because immunosuppression can reactivate infections, but also because a false-positive result on rheumatoid factor antibody testing can occur in the setting of chronic infections. Patients with congestive heart failure should avoid anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy for RA. Skin cancer screening is important in all patients with RA receiving biologic therapy.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

There is a risk of TB activation with the use of biologic therapy in patients with RA.26 It is recommended that patients be screened for latent TB infection with tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma release assay before starting biologic immunosuppression.16 Patients who are diagnosed with latent TB infection should complete at least one month of treatment for latent TB infection before initiation of biologic therapy for RA. For patients who are diagnosed with active TB infection, the complete course of anti-TB therapy should be taken before starting biologics.16

Active hepatitis B virus infection should be screened for and treated if present in patients with RA receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Even patients with occult hepatitis B virus infection (e.g., negative hepatitis B surface antigen, positive hepatitis B core antibody, negative hepatitis B surface antibody, positive hepatitis B virus DNA) are at risk of hepatitis reactivation with immunosuppressive treatment, and can benefit from antiviral treatment.27 Patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection also require monitoring and antiviral therapy with use of immunosuppression to treat RA. In a systematic review of 153 patients with hepatitis C virus infection who were treated with anti-TNF therapy, 9% of patients with RA had increased hepatitis C viral load or elevated liver enzyme levels.28

Patients with RA should be screened for skin malignancy, and those with a history of skin cancer should use nonbiologic DMARDs rather than biologic treatment.31 Studies of a Swedish RA cohort suggest that there is one additional case of squamous cell carcinoma for every 1,600 person-years of anti-TNF treatment and 20 cases of malignant melanoma for every 100,000 person-years.31,32

Can Patients with RA Taper or Discontinue Medication Use and Remain in Remission?

Tapering and discontinuing medication use while maintaining remission is possible. Patients who have been in remission for more than six months on a stable medication regimen and who test negative for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies are most likely to maintain remission without medication.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A randomized clinical trial compared remission rates at 12 months in patients who continued, tapered, or discontinued DMARD therapy. All patients in the study were on stable DMARDs and in clinical remission for at least six months at baseline. The first group of patients maintained the same DMARD regimen, the second group tapered DMARDs by 50%, and the third group tapered DMARDs for six months and then discontinued all DMARDs.35 Approximately 84% of the patients who continued full DMARD treatment remained in remission, compared with 61% in the tapering arm and 48% in the discontinuation arm.35 Patients who tested positive for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies were more likely to relapse with medication tapering.35 Another randomized clinical trial explored drug cessation in patients with early RA who achieved remission with etanercept (Enbrel) and methotrexate after nine months. Patients who received etanercept at a tapered dosage plus methotrexate were more likely to maintain remission vs. patients receiving methotrexate alone or placebo.36

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms rheumatoid arthritis, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic agents, extra-articular manifestations of RA, and tapering RA medications. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, and UpToDate. Search dates: September 2016 and October 2017.