This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(9):595-602

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Women often see their primary care physicians for common acute conditions during pregnancy. These conditions may be caused by pregnancy (obstetric problems) or worsened by pregnancy (obstetrically aggravated problems), or they may require special consideration during pregnancy because of maternal or fetal risks (nonobstetric problems). Primary care physicians should know the differential diagnosis for common conditions during pregnancy and recognize the important findings of obstetric and urgent nonobstetric problems. The family physician can evaluate and treat most nonobstetric problems, although obstetric problems require referral to a primary maternity care clinician. A tiered approach, including routinely looking for all-cause red flag symptoms and signs, while remaining aware of estimated gestational age, allows for high-quality care and shared decision making between the family physician and the pregnant patient. When treating common causes of nausea and epigastric pain/gastroesophageal reflux, lifestyle modifications are considered the safest and first-choice therapy, followed by well-established low-risk therapies, such as vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) and doxylamine for nausea, and antacids not containing salicylates (found in bismuth combination products) for gastroesophageal reflux. Other common conditions during pregnancy are best treated with low-risk therapies, such as using antihistamines or topical steroids for rashes, first-generation cephalosporins or amoxicillin for cystitis, and physical therapy and acetaminophen for low back pain and headaches.

Women often see their primary care physicians for common acute conditions during pregnancy, even if they are not the primary maternity care clinician. Some conditions are caused directly by pregnancy (obstetric problems) or are worsened by pregnancy (obstetrically aggravated problems), and others require special consideration during pregnancy because of maternal or fetal risks (nonobstetric problems).1 Table 1 outlines the causes of common symptoms during pregnancy.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy should begin with lifestyle modifications. Other treatments, including P6 acupressure, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), doxylamine, and prescription antiemetics, can be added as needed. | B | 7, 8, 10 |

| Pregnant women with more than 100,000 colony-forming units of one bacterial species on urine culture should be treated with antibiotics to prevent pyelonephritis. | A | 32 |

| Initial choices for treating musculoskeletal back pain in pregnancy include exercise and physical therapy, but additional therapy with acetaminophen, warm baths, acupuncture, support devices, or epidural steroids may be needed. | C | 36, 37 |

| Pregnant women with new-onset headaches or a new type of headache should be further evaluated to distinguish urgent or emergent causes (e.g., meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage) from common preexisting conditions (e.g., sinusitis, tension or migraine headaches). Preeclampsia must be ruled out if headaches occur after 20 weeks' gestation. | C | 40, 42 |

| Symptom | Important accompanying signs and symptoms | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea and vomiting | General: weight loss, dehydration, high-normal or high serum creatinine level, occurring before four weeks (nonobstetric causes) or persisting after 12 weeks estimated gestational age (molar pregnancy) | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: gastroenteritis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, thyroid disease, kidney stones, gallbladder problems |

| Nonobstetric: diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, neck/thyroid pain or enlargement | Obstetric: nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, hyperemesis gravidarum, molar pregnancy, multiple gestation | |

| Obstetric: vaginal bleeding, large uterus for estimated gestational age, refractory | ||

| Abdominal pain | General: nausea and vomiting, epigastric/right upper quadrant pain, weight loss, dehydration, high-normal or high serum creatinine level | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, cholecystitis, cystitis, pyelonephritis, appendicitis, kidney stones, constipation, gastritis |

| Nonobstetric: change with eating and drinking, blood in stool or emesis, melena, fever, jaundice | Obstetric: preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, abruption, intrauterine fetal demise, round ligament strain, preterm labor | |

| Obstetric: headaches, vision changes, low platelet counts, swelling | ||

| Cough | General: dyspnea, hypoxemia | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: acute/chronic asthma, viral upper respiratory tract infection (including influenza), allergic rhinitis, pneumonia, pertussis |

| Nonobstetric: wheeze, hemoptysis, fever, myalgia, purulent nasal discharge or sputum | Obstetric: physiologic rhinitis of pregnancy | |

| Rash | General: pustules, vesicles/blisters, erythema, pruritus | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: acne, eczema, psoriasis, cellulitis/abscess, herpes zoster, human papillomavirus infection, fungal infection, scabies, impetigo, folliculitis |

| Nonobstetric: condyloma, scaling, lichenification, ulcers, secondary rash on preexisting condition (e.g., eczema, moles) | Obstetric: physiologic pigment change (melasma, linea nigra), striae gravidarum, PUPPP, intrahepatic cholestasis, pustular psoriasis (impetigo herpetiformis), pemphigoid gestationis, atopic eruption of pregnancy (prurigo of pregnancy) | |

| Obstetric: pigmented patches/lines, pruritus with or without papules/blisters, spares the umbilicus (PUPPP) | ||

| Dysuria | General: dehydration, uterine contractions | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: cystitis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, pyelonephritis, sexually transmitted urethritis, herpes genitalis, urolithiasis, recurrent urinary tract infection |

| Nonobstetric: other urinary symptoms; vulvovaginal discharge, itching, or burning; fever; nausea or vomiting; costovertebral angle tenderness; colicky flank pain; gross hematuria; prior urinary tract infection | ||

| Obstetric: nonspecific (urinary frequency and incontinence common) | ||

| Low back pain | General: poor function, deconditioning | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: musculoskeletal strain, loosening of sacroiliac joint, disc herniation, cauda equina syndrome, sciatic nerve/lumbar plexus pressure, pyelonephritis, urolithiasis, sacroiliitis, joint laxity, herniated nucleus pulposus Obstetric: abruption, intrauterine fetal demise, preterm or term labor |

| ||

| Obstetric: history or evidence of an accident/fall/trauma, vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal pain, change in fetal movement, loss of fluid, uterine tenderness, uterine contractions, urinary tract symptoms | ||

| Headache | General: new-onset headache or new headache type, rapidly increasing frequency of headaches | Nonobstetric or obstetrically aggravated: tension or migraine headache, meningitis, sinusitis (viral, allergic, bacterial), subarachnoid hemorrhage, brain tumor |

| Nonobstetric: purulent nasal discharge, nausea and vomiting, focal neurologic signs or symptoms, fever, neck pain/stiffness, sudden thunderclap headache | Obstetric: preeclampsia | |

| Obstetric: visual disturbance (scotomata), proteinuria, hypertension |

General Considerations for Pregnant Patients

To ensure appropriate evaluation and treatment, an accurate calculation of the estimated gestational age is essential. Some symptoms are trimester-specific, whereas others (e.g., abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding) may present throughout the pregnancy (Table 2). Symptoms and signs may vary in importance depending on whether they are caused by pregnancy or are simply common acute findings that may be unrelated to the pregnancy.

| Symptom | Possible obstetric causes by estimated gestational age | Nonobstetric causes |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 0 to 20 weeks

20 to 40 weeks

| Appendicitis Cholecystitis Constipation Cystitis Gastritis Gastroesophageal reflux disease Kidney stones Peptic ulcer disease Pyelonephritis |

| Headache | 20 to 40 weeks

| Brain tumor Meningitis Sinusitis Subarachnoid hemorrhage Tension or migraine headache |

| Vaginal bleeding | 0 to 20 weeks

20 to 40 weeks

| Cervicitis Nonvaginal sources (hemorrhoid, anal fissure, vulvar varicosity) |

Physiologic changes in pregnancy lead to predictable problems that may impact the patient's function and health, such as musculoskeletal aches and pains, nasal congestion, and nausea. Given the potential risks of some treatments to the fetus, as well as possible maternal adverse effects, the decision of whether and how to treat is based on benefits vs. potential harms.2

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's new labeling system for safety of medications during pregnancy and breastfeeding no longer uses alphabetical ratings (A, B, C, D, and X) and provides more guidance on risks, including information based on gestational age and lactation and reproductive risks.3,4 After identifying the risks and benefits of treatments, family physicians can engage in shared decision making with their pregnant patients. Table 3 summarizes the evaluation and treatment of common symptoms during pregnancy.5–42

| Common symptom | Evaluation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea and vomiting | For all: weight, blood pressure, pulse, assessment of oral mucous membranes, orthostatic blood pressure measurement, abdominal examination | For nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

|

| If abdominal pain or tenderness: CBC; consider ultrasonography of gallbladder or appendix | ||

| If severe, refractory, begins before four weeks, or persists after 12 weeks estimated gestational age5,6: comprehensive metabolic panel; thyroid-stimulating hormone and beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels; transabdominal ultrasonography; consultation with primary maternity care clinician if evidence of dehydration, poor weight gain, molar pregnancy, or thyroid dysfunction | ||

| Epigastric pain/gastroesophageal reflux | For all: temperature, blood pressure, pulse, weight, assessment of oral mucous membranes, UA to check for protein | For gastroesophageal reflux of pregnancy

|

| If fever or abdominal pain: CBC, LFTs12 | For severe or refractory cases: proton pump inhibitors, only in consultation with primary maternity care clinician14–16 | |

| If nausea, vomiting, colicky pain, positive Murphy sign, or fever: CBC for white blood cell count, lipase, bilirubin, LFTs, right upper quadrant ultrasonography12 | ||

| If blood in the stool, emesis, or melena: CBC for hemoglobin and hematocrit, fecal occult blood test12 | ||

| If begins after 20 weeks estimated gestational age and there are headaches, vision changes, abdominal pain, high blood pressure, or proteinuria: CBC for platelets, LFTs, consultation with primary maternity care clinician12 | ||

| Cough | For all: vital signs with pulse oximetry; ears, nose, throat, and lung examination17 | Prevention: hand/cough hygiene, hydration, inactivated influenza and Tdap (tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis) vaccines18,19 |

| If wheezing, fever, hypoxemia, shortness of breath, hemoptysis: consider chest radiography, CBC17 | For specific causes | |

| If myalgia or fever, or it is influenza season: consider empiric influenza therapy, hospitalization, and consultation with primary maternity care clinician17 | ||

| Rash | For all: full examination of rash; note distribution, appearance, associated symptoms, and timing | Prevention: preconception varicella vaccine (contraindicated during pregnancy) |

Based on characteristics

| Continue most therapies for chronic conditions,22–27 except for methotrexate and retinoids (contraindicated in pregnancy) | |

| If diagnosis still unclear: consider biopsy | Selective use of acute therapy: topical steroids, antihistamines, topical antifungals, antibiotics | |

| Consultation with primary maternity care clinician when considering antivirals for varicella or herpes, or ursodiol (Actigall) for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy28,29 | ||

| Dysuria | For all: vital signs, assessment of mucous membranes, examination for abdominal/costovertebral angle tenderness, vulvar inspection, UA with microscopy, urine culture30,31 | For cystitis/asymptomatic bacteriuria |

| If UA results show a substantial number of epithelial cells, physiologic leukorrhea contamination should be suspected unless culture shows more than 100,000 colony-forming units of one organism32–34 | For vulvovaginal candidiasis

| |

| If no clear diagnosis and UA findings are abnormal: vaginal examination with wet mount and urinary gonorrhea/chlamydia testing, empiric antibiotics for urinary tract infection pending urine culture results | For pyelonephritis | |

| If costovertebral angle tenderness or fever: CBC, renal ultrasonography, intravenous antibiotics | ||

| Occurs at more than 20 weeks estimated gestational age: consultation with primary maternity care clinician to monitor for preterm labor and fetal well-being | ||

| If colicky flank pain or gross hematuria: renal ultrasonography, urology consultation | ||

| Low back pain | If there are urologic red flags (Table 1): UA with culture, consider renal ultrasonography and urology consultation | For musculoskeletal low back pain: low back stretching exercises, water exercises, physical therapy, job and activity modification, warm baths, lumbar traction, supportive devices (prenatal cradles, sacroiliac joint belts), acetaminophen, acupuncture36,37 |

| If there are neurologic red flags (Table 1): neurosurgical consultation, magnetic resonance imaging of spine | If refractory and no red flags: consider epidural steroids36,37 | |

| If there are obstetric red flags: consultation with primary maternity care clinician | ||

| Headache | For all: blood pressure, UA, neurologic examination, funduscopy, nasal examination38 | For sinusitis: amoxicillin |

| If headache not relieved with acetaminophen and rest, or there is scotomata, elevated blood pressure, or proteinuria: CBC, LFTs, consultation with primary maternity care clinician | For suspected meningitis: third-generation cephalosporins; consider vancomycin, acyclovir, dexamethasone39–41 | |

| If focal neurologic signs or symptoms: shielded noncontrast head CT, neurology consultation; if CT is negative, consider magnetic resonance venography or angiography39–41 | For migraine

| |

| If meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected: shielded noncontrast CT; consider lumbar puncture if CT results are normal39–41 |

Common Symptoms During Pregnancy

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

About one-half of pregnant women have nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.43 Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy increases the risk of dehydration, poor function, poor weight gain, and, if severe, acute renal failure and impaired fetal growth. Benign nausea and vomiting of pregnancy is the most common obstetric cause and tends to begin by four weeks estimated gestational age and resolve by the end of 12 weeks estimated gestational age.5 If it begins or ends outside of these intervals or is severe or refractory, less common obstetric causes (e.g., multiple gestation, molar pregnancy) and nonobstetric causes (e.g., gallbladder problems, thyroid disease) should be considered.6

Despite increased availability of prescription therapies for nausea in pregnancy, not all women require prescription antiemetics, and the safety of these therapies is not as clear as conservative treatments.7,8 First-line treatments include low-risk lifestyle modifications, such as eating frequent small meals throughout the day to keep the stomach from becoming too empty or full, and avoiding foods that further slow gastric emptying (high-protein or fatty foods) or have intense smells or tastes.7,8 If these conservative approaches are ineffective, other therapies, including vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), over-the-counter antihistamines such as doxylamine, and natural ginger (less than 1,500 mg per day), can be added in a stepwise fashion.7,9,10 There is weak evidence that P6 acupressure can also be a treatment option7 (a video of this therapy is available). [corrected]

Combination doxylamine 10 mg/pyridoxine 10 mg (Diclegis) is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. The combination may improve compliance because it includes fewer pills but can also be much more expensive than each medication alone.

Prescribed antiemetics such as metoclopramide (Reglan) and trimethobenzamide (Tigan) are reserved for severe or refractory cases.9,10 However, there are safety concerns with some prescribed antiemetics, such as promethazine, which has a risk of neonatal respiratory depression near term or during labor, and ondansetron (Zofran), which physicians should consider avoiding in the first trimester because of conflicting data on the risk of teratogenicity.9–11

EPIGASTRIC PAIN/GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is common in pregnancy and is attributed to progesterone-mediated relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, which increases the frequency and severity of gastric reflux. Other conditions that present as heartburn-like discomfort during pregnancy include peptic ulcer disease, preeclampsia (i.e., HELLP [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count] syndrome),12 cholecystitis, and acute fatty liver of pregnancy.

An elevated alkaline phosphatase level is normal during pregnancy. However, an elevated lipase, bilirubin, or transaminase level requires ultrasound evaluation for cholecystitis, especially in the presence of severe colicky abdominal pain or other suggestive findings (e.g., positive Murphy sign, leukocytosis, fever). Peptic ulcer disease should be considered if results of laboratory tests such as complete blood count, liver panel, and lipase level are normal and reflux therapies are ineffective.

No one therapy for gastroesophageal reflux has been proven superior; therefore, prioritizing therapy depends on relative risks and adverse effects.13 Initial therapies for gastroesophageal reflux of pregnancy include low-risk lifestyle interventions such as eating frequent small meals and avoiding smoking, caffeine, peppermint, and chocolate. Next choices generally include over-the-counter antacids that do not contain salicylates (found in bismuth combination products) and over-the-counter cimetidine (Tagamet), famotidine (Pepcid), or ranitidine (Zantac). Proton pump inhibitors are reserved for severe or refractory cases because of cautions advised during pregnancy and should be considered only in consultation with a primary maternity care clinician.14–16 Whatever the suspected cause, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed only for serious indications, such as significant gastrointestinal bleeding, and is safer in the second trimester compared with the first.44

COUGH

Apart from physiologic rhinitis of pregnancy, upper respiratory tract conditions are not usually caused by the normal hormonal, anatomic, and circulatory effects of pregnancy.45 In patients with preexisting chronic conditions, such as asthma, management of the condition is similar during pregnancy, although therapies can be adjusted based on safety data.46,47 Evaluation of acute cough should consider acute asthma exacerbation, allergic reaction, and viral and bacterial infections.17 Although cough alone is not indicative of pulmonary embolism, because of the increased risk of pulmonary embolism in pregnancy, the condition should be considered whenever cough is associated with chest pain or shortness of breath.

Common symptoms associated with cough include nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, pharyngitis, shortness of breath, and chest discomfort. In the absence of a concerning diagnosis, the symptoms can be treated with the usual prescription and over-the-counter therapies.20,21 Prevention of upper respiratory tract illnesses through hand/cough hygiene and the inactivated influenza and Tdap (tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis) vaccines is essential. Although a case-control study found a possible relationship between the influenza vaccine and miscarriage in a subset of patients, current evidence supports the safety of the vaccine in pregnancy.18,19

RASH

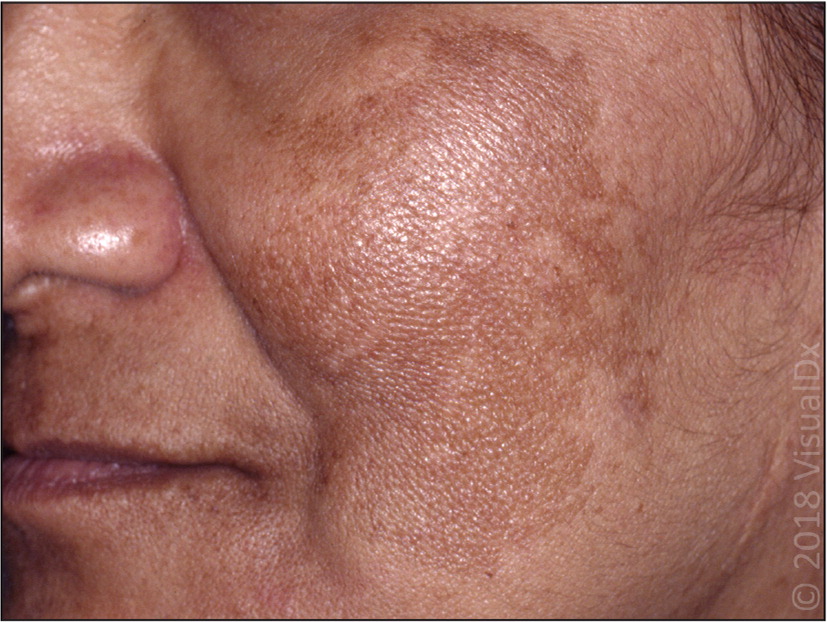

Skin conditions that arise or worsen during pregnancy can be due to hormonal and other physiologic changes of pregnancy.48,49 Most of these conditions do not impact pregnancy outcomes.50,51 Benign skin conditions of pregnancy include melasma (eFigure A) and striae gravidarum (eFigure B). Signs and symptoms of dermatoses in pregnancy include pruritus, papules, and plaques. Notably, pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy spare the umbilicus (eFigure C). Treatment of skin conditions in pregnancy typically involves antihistamines, topical steroids, or oral steroid tapers.22–27

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, which causes pruritus without a rash, has been associated with increased fetal mortality, warranting antenatal surveillance in consultation with a primary maternity care clinician. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is treated with ursodiol (Actigall) in consultation with a primary maternity care clinician, although the therapy leads to only slightly better fetal and maternal outcomes than placebo. Cholestyramine (Questran) has been used, but it only reduces pruritus.28 Delivery by 35 to 37 weeks estimated gestational age may be warranted if bile acid levels are more than 16.3 mcg per mL (40 μmol per L).29

DYSURIA

Although frequency and urgency are normal as the uterus enlarges in the later stages of pregnancy, dysuria may be a result of cystitis, pyelonephritis, or sexually transmitted infections, which can lead to maternal and fetal morbidity.30,31 In pregnant women who have more than 100,000 colony-forming units of one bacterial species on urine culture, starting antibiotics early is necessary to reduce the risk of pyelonephritis, even in those who are asymptomatic.32–34

The choice of an appropriate oral antibiotic (e.g., penicillins, such as amoxicillin; first-generation cephalosporins; erythromycin; nitrofurantoin) is based on known drug risks during pregnancy, patient drug allergies, and bacterial resistance patterns.35 Nitrofurantoin is not used at term because of the risk of severe hemolytic anemia following birth. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is generally not recommended for use in pregnancy because of risks of neural tube defects in early pregnancy, as well as kernicterus in the newborn and permanent neonatal neurologic damage. [corrected] A systematic review found that of the nonantibiotic measures taken to prevent urinary tract infections during pregnancy, only genital hygiene can be recommended in practice.52

Because bacteriuria increases the risk of preterm labor, urinary cultures should be checked after treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, or pyelonephritis to ensure bacteriuria resolves and does not recur. A follow-up urinary culture should be performed for test of cure. It is prudent to repeat follow-up cultures periodically.

LOW BACK PAIN

Low back pain often occurs during pregnancy because of musculoskeletal strain from increased lordosis and soft tissue laxity. However, urologic and neurologic red flags (Table 1) should be identified and treated. Acute low back pain should be more rigorously evaluated when associated with a history of trauma, vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal pain, loss of fluid, uterine contractions, uterine tenderness, change in fetal movement, or urinary tract symptoms. This evaluation (in consultation with a primary maternity care clinician) should be focused on ruling out obstetric complications of trauma, such as abruption, combined with systematic monitoring for uterine contractions and fetal heart rate, and possibly fetal ultrasonography.36

Treatment of back pain in pregnant women targets alleviating musculoskeletal strain with exercises and physical therapy. Additional therapy such as acetaminophen, acupuncture, support devices, warm baths, or epidural steroids may be needed.36,37 A systematic review found that osteopathic manipulative treatment may improve function and reduce pelvic girdle and low back pain during and after pregnancy.53

HEADACHES

New-onset headaches or a new type of headache in pregnancy warrants further evaluation to distinguish urgent or emergent causes (e.g., meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage) from common preexisting conditions (e.g., sinusitis, tension or migraine headaches).38,40,42 Preeclampsia must be ruled out in all pregnant women with headache who are more than 20 weeks' gestation by monitoring serial blood pressures and assessing urine for protein in consultation with a primary maternity care clinician.40,42

Tension and migraine headaches can lead to significant morbidity.42 Acetaminophen is an initial, low-risk therapy. Other drugs such as sumatriptan (Imitrex), dexamethasone (brief, isolated use; avoid during the first trimester), and ketorolac (second trimester only) can be used with caution, after the potential risks are explained to the patient, for severe or refractory headaches that significantly affect the patient's nutrition, hydration, or functioning. When headaches are associated with sudden onset, focal neurologic symptoms and findings, fever, or neck stiffness, further emergent workup, initially with shielded head computed tomography and possibly lumbar puncture, is warranted.39–41

Data Sources: The authors searched the Cochrane database, National Guideline Clearinghouse, UpToDate, and Ovid/PubMed, as well as references within these sources. Key words included pregnancy, rash, skin, asthma, upper respiratory infection, infection, nonobstetric complaints, nausea, dyspepsia, heartburn, low back pain, headache, urinary tract infection, back pain, and lumbar pain. Search dates: March 1 to November 7, 2016, and June 19 to July 3, 2018.