Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(6):350-356

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common diagnosis in childhood acute sick visits. By three years of age, 50% to 85% of children will have at least one episode of AOM. Symptoms may include ear pain (rubbing, tugging, or holding the ear may be a sign of pain), fever, irritability, otorrhea, anorexia, and sometimes vomiting or lethargy. AOM is diagnosed in symptomatic children with moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane or new-onset otorrhea not caused by acute otitis externa, and in children with mild bulging and either recent-onset ear pain (less than 48 hours) or intense erythema of the tympanic membrane. Treatment includes pain management plus observation or antibiotics, depending on the patient's age, severity of symptoms, and whether the AOM is unilateral or bilateral. When antibiotics are used, high-dose amoxicillin (80 to 90 mg per kg per day in two divided doses) is first-line therapy unless the patient has taken amoxicillin for AOM in the previous 30 days or has concomitant purulent conjunctivitis; amoxicillin/clavulanate is typically used in this case. Cefdinir or azithromycin should be the first-line antibiotic in those with penicillin allergy based on risk of cephalosporin allergy. Tympanostomy tubes should be considered in children with three or more episodes of AOM within six months or four episodes within one year with one episode in the preceding six months. Pneumococcal and influenza vaccines and exclusive breastfeeding until at least six months of age can reduce the risk of AOM.

Acute otitis media (AOM) is commonly diagnosed in children in primary care offices. It is also a leading contributor to antibiotic prescriptions and medical costs in children.1 This article provides a summary and review of the best, most recent evidence to guide the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children two to 12 years of age with nonsevere symptoms if the observation option is reasonable. | American Academy of Family Physicians |

Epidemiology

AOM is the most common diagnosis in childhood acute sick visits, accounting for 13.6 million office visits among children annually.1

The incidence of AOM peaks between six and 15 months of age.2

AOM is marginally more common in boys than in girls.2

By three years of age, 50% to 85% of children experience at least one episode of AOM. However, after 24 months of age, the risk decreases with increasing age.2,3

Risk factors for AOM are shown in Table 1.2,4 The most common causative bacterial species are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.5,6

| Nonmodifiable risk factors |

| Age younger than five years |

| Craniofacial abnormalities |

| Family history of ear infections |

| Low birth weight (less than 2.5 kg [5 lb, 8 oz]) |

| Male sex |

| Premature birth (before 37 weeks of gestation) |

| Prior ear infections |

| Recent viral upper respiratory tract infection |

| White ethnicity |

| Potentially modifiable risk factors |

| Exposure to tobacco smoke or environmental air pollution |

| Factors increasing crowded living conditions (e.g., cold seasons, low socioeconomic level, day care/school) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Lack of breastfeeding |

| Pacifier use after six months of age |

| Supine bottle feeding (bottle propping) |

Diagnosis

In addition to ear pain, AOM is commonly associated with fever, irritability, otorrhea, anorexia, and sometimes vomiting or lethargy.2

The diagnosis is made clinically using common symptoms and findings on examination of the tympanic membrane.7

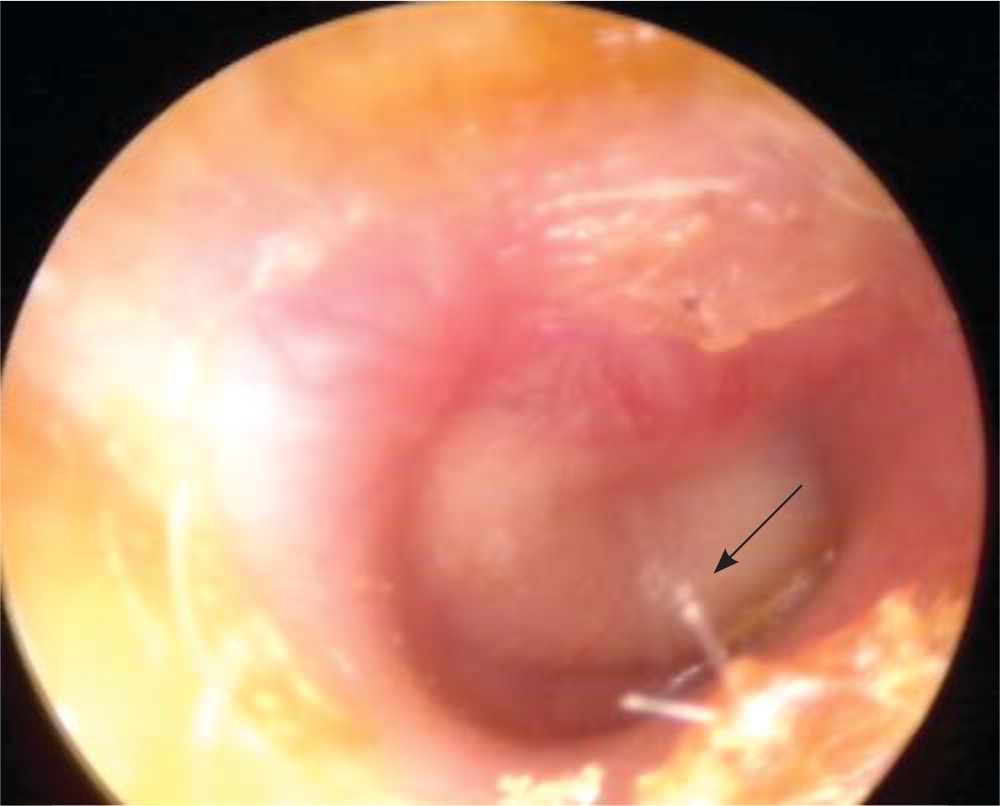

AOM should be diagnosed in symptomatic children with moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane (Figure 14) or new-onset otorrhea not caused by otitis externa.7 It can also be diagnosed in children with mild bulging and either recent-onset ear pain (less than 48 hours) or intense erythema of the tympanic membrane. Ear pain can be assumed in fussy, nonverbal children who hold, tug, or rub the ear.7

AOM should not be diagnosed without evidence of middle ear effusion on pneumatic otoscopy or tympanometry.7

Otitis media with effusion is often misdiagnosed as AOM. Otitis media with effusion can be distinguished on physical examination by a neutral or retracted (not bulging) tympanic membrane with an amber or blue (not white or pale yellow) hue. Air fluid levels, however, may be present in both conditions.8

Pneumatic otoscopy should be used for the assessment of the tympanic membrane.4,7 Pneumatic otoscopy is up to 94% sensitive and 90% specific for identifying middle ear effusion.4,9

Tympanometry can be used as an adjunct to pneumatic otoscopy. Tympanometry is also 70% to 94% sensitive and 90% specific for identifying middle ear effusion.4,9

Tympanocentesis is the diagnostic standard for identifying the causative bacteria in the middle ear fluid. However, this procedure is impractical in a primary care clinic, and it rarely changes initial management because the common bacterial pathogens are predictable.5 However, tympanocentesis may be considered to guide treatment in children with ongoing severe symptoms despite treatment with multiple antibiotics by identifying the offending pathogen and its antibiotic susceptibility.7

Treatment

| Examination findings | Treatment |

|---|---|

| AOM with otorrhea | Antibiotic therapy |

| AOM with severe symptoms* or if follow-up cannot be guaranteed | Antibiotic therapy |

| Bilateral AOM without otorrhea | Six months to two years of age: antibiotic therapy |

| Two years and older: antibiotic therapy or observation without initial antibiotic treatment† | |

| Unilateral AOM without otorrhea | Antibiotic therapy or observation without initial antibiotic treatment† |

ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

The resolution rate of AOM in children is 81% without antibiotic treatment vs. 93% with antibiotic treatment.1 Thus, antibiotics have limited benefits compared with the potential adverse effects, such as rash, vomiting, or diarrhea.10

Antibiotic treatment of AOM in children does not decrease early pain (before 24 hours), hearing loss at three months, or recurrence within 30 days.10

Antibiotic treatment has some beneficial effect on pain after 24 hours (up to 12 days), number of tympanic membrane perforations, and contralateral otitis media.10 Children younger than two years with bilateral otitis media or otitis media with otorrhea benefit most from antibiotics.10

If antibiotics are used for AOM, high-dose amoxicillin (80 to 90 mg per kg per day in two divided doses) is first-line therapy, unless the child has taken antibiotics for AOM in the previous 30 days, has purulent conjunctivitis, or has a penicillin allergy.7

Observation for 48 to 72 hours with deferment of antibiotics should be considered in lower-risk children with AOM.7,10

Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) should be the initial antibiotic for children who have taken amoxicillin for AOM in the previous 30 days or who have purulent conjunctivitis.7

Single-dose intramuscular ceftriaxone is as effective as amoxicillin for isolated episodes of AOM. However, ceftriaxone should not be used as a first-line treatment, because there are limited options if treatment fails.7

Cefdinir or azithromycin (Zithromax) should be the first-line antibiotic in those with penicillin allergy based on risk of cephalosporin allergy.

Antibiotic treatment failure is defined as diagnosis of AOM in the 30 days following treatment initiation or severe symptoms that do not resolve within 48 to 72 hours of treatment initiation and unimproved findings on tympanic membrane examination.7

Lack of resolution of AOM is likely secondary to beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae or M. catarrhalis; amoxicillin/clavulanate should be used for treatment if amoxicillin fails.7

Duration of therapy is based on patient age and severity of symptoms. A 10-day course of antibiotics is recommended if the child is younger than two years or has severe symptoms. A five- to seven-day course is effective if the child is two years or older and does not have severe symptoms.7

Figure 2 is an algorithm for the treatment of AOM in children requiring antibiotics.7

PAIN MANAGEMENT

Pain should be treated as needed in children with AOM.7 Monotherapy with oral ibuprofen or acetaminophen provides short-term (less than 48 hours) relief of ear pain secondary to AOM. Evidence is insufficient to establish that one of these medications is superior to the other or that combined therapy provides better pain relief.11 Caregivers should be counseled on appropriate use of these pain medications.7

Topical anesthetic eardrops and naturopathic eardrops have been found to decrease pain in some small studies, but overall evidence is insufficient to recommend routine use.12,13 They should be avoided if there is any concern for tympanic membrane perforation.7

There is limited evidence for the benefit of home remedies, such as distraction, external application of heat or cold, and oil drops into the external auditory canal.7

For children younger than two years, follow-up of AOM can typically occur at the next scheduled wellness visit or three months after completing treatment to ensure resolution of middle ear fluid. For children two years and older without an upcoming visit or children with recurrent AOM, reevaluation within three months of completing treatment should be considered to ensure resolution of middle ear effusion.14

Prevention

Susceptibility to AOM is complex and not well understood, and it likely includes a combination of genetic, anatomic, and environmental factors.2

The previous heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine reduced the relative risk of AOM by 5% to 6% in high-risk children and up to 6% in low-risk children. For AOM caused specifically by pneumococcus, the relative risk reduction was 20% to 25%. It is difficult to assess the effect of the current 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar 13) on prevention of AOM, but a recent study showed that the extra six serotypes result in an 86% risk reduction of pneumococcal-specific AOM in middle ear fluid compared with the heptavalent vaccine.16 All children should receive pneumococcal vaccination according to guidelines from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.17

AOM often follows a viral upper respiratory tract infection. Influenza vaccination leads to a 4% absolute reduction in AOM episodes and a 30% to 55% reduction in AOM during the respiratory illness season.7,18 Children older than six months should receive annual influenza vaccination.19

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of AOM. Longer duration of breastfeeding provides greater protection for children younger than two years.20 Exclusive breastfeeding until six months of age reduces the risk by 43%.7,20

Xylitol (chewing gum, lozenges, or syrup) reduces the occurrence of AOM in children attending day care by 25%. Evidence for the benefit of xylitol in children prone to otitis media or in children with an acute respiratory infection is inconclusive. Adverse effects of xylitol include abdominal pain and rash.21 Xylitol must be used multiple times per day for the entire respiratory illness season to be effective, leading to poor compliance.22

Evidence is mixed on the benefit of zinc supplementation for the prevention of AOM in healthy children younger than five years.23

Weak evidence exists for eliminating tobacco smoke exposure, avoiding supine bottle feeding (bottle propping), and reducing or eliminating pacifier use after six months of age in the prevention of AOM and AOM recurrences. However, given the risk of tobacco smoke exposure on overall health, avoidance is recommended.7,24

Recurrent AOM

Referral to an otolaryngologist for possible tympanostomy tube placement should be considered in children with three or more episodes of AOM within six months or four episodes within one year with one episode in the preceding six months.7

Tympanostomy tubes should not be placed in children with recurrent AOM if no middle ear effusion is noted at the time of otolaryngologist evaluation.25

Possible long-term sequelae of tympanostomy tubes include structural changes to the tympanic membrane, such as focal atrophy, tympanosclerosis, retraction pockets, and chronic perforation; cholesteatoma; and chronic otorrhea.26 These risks should be weighed against the risks associated with chronic otitis media with effusion, including decreased academic performance, vestibular problems, behavioral issues, and overall decreased quality of life.25

Prophylactic antibiotics should not be prescribed to reduce the frequency of AOM episodes in children with recurrent AOM. They have not been shown to be effective and increase rates of microbial resistance.7

Special Considerations for Infants

Infants eight weeks and younger are at greater risk of severe sequelae from AOM, including sepsis, meningitis, and mastoiditis.4

Group B streptococci, gram-negative enteric bacteria, and Chlamydia trachomatis are common pathogens found in the middle ear fluid of neonates younger than two weeks, and a full sepsis workup should be completed for any neonate younger than two weeks with fever and apparent AOM.26,27 Antibiotics should be initiated for sepsis as indicated. Amoxicillin is the first-line antibiotic for neonates older than two weeks.26,27

Special Considerations for Adults

Treatment of AOM in adults is largely extrapolated from studies of treatment in children, with amoxicillin as the recommended first-line antibiotic.

There are no data on observation instead of treatment in adults with AOM. Therefore, adults should be treated with antibiotics at initial presentation to prevent complications.

Adults with recurrent AOM (more than two episodes per year) or otitis media with effusion that persists for more than six weeks should be referred to an otolaryngologist to be evaluated for mechanical eustachian tube obstruction.4

Practical Considerations

To allow visualization of the tympanic membrane, attempts should be made to safely remove cerumen obstruction/impaction using ceruminolytics, irrigation, or manual removal. No one ceruminolytic has been shown to be superior.28 If visualization remains difficult, cerumen removal should be attempted again the next day or the patient should be referred to an otolaryngologist.29 Cerumen impaction was covered previously in American Family Physician.30

Tympanometry can be difficult in young children. If adequate readings cannot be obtained, cerumen should be removed and proper fit of the device tip should be ensured, then tympanometry reattempted. If this fails, visualized insufflation may be attempted to look for movement of the tympanic membrane.

Other causes of ear pain and erythema of the tympanic membranes, including vascular engorgement from crying, viral and hemorrhagic myringitis, and aberrant tympanic membrane vessels, should be considered before diagnosing AOM.31

Parents should be counseled that fever and ear pain may persist for 48 to 72 hours after initiation of antibiotics. However, parents should seek care immediately if the child is vomiting or has a high fever, headaches, or pain behind the ear.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Harmes, et al.4 ; Ramakrishnan, et al.32 ; and Pichichero.33

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms pediatric, children, acute otitis media, evaluation, treatment, and antibiotic management. We reviewed the updated Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence Report on the management of acute otitis media, which included a systematic review of the literature through October 2018. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, Clinical Evidence, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane database. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also searched. Search dates: September to October 2018 and May 2019.

The views expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. government, Department of Defense, or Department of the Air Force.