Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(1):24-33

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Common anorectal conditions include hemorrhoids, perianal pruritus, anal fissures, functional rectal pain, perianal abscess, condyloma, rectal prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Although these are benign conditions, symptoms can be similar to those of cancer, so malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis. History and examination, including anoscopy, are usually sufficient for diagnosing these conditions, although additional testing is needed in some situations. The primary treatment for hemorrhoids is fiber supplementation. Patients who do not improve and those with large high-grade hemorrhoids should be referred for surgery. Acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoids should be excised. Perianal pruritus should be treated with hygienic measures, barrier emollients, and low-dose topical corticosteroids. Capsaicin cream and tacrolimus ointment are effective for recalcitrant cases. Treatment of acute anal fissures with pain and bleeding involves adequate fluid and fiber intake. Chronic anal fissures should be treated with topical nitrates or calcium channel blockers, with surgery for patients who do not respond to medical management. Patients with functional rectal pain should be treated with warm baths, fiber supplementation, and biofeedback. Patients with superficial perianal abscesses not involving the sphincter should undergo office-based drainage; patients with more extensive abscesses or possible fistulas should be referred for surgery. Condylomata can be managed with topical medicines, excision, or destruction. Patients with rectal prolapse should be referred for surgical evaluation. Biofeedback is a first-line treatment for fecal incontinence, but antidiarrheal agents are useful if diarrhea is involved, and fiber and laxatives may be used if impaction is present. Colostomy can help improve quality of life for patients with severe fecal incontinence.

Anorectal conditions are commonly seen in primary care settings.1 Although the differential diagnosis is broad, a history coupled with an external examination (with and without straining), a digital rectal examination, and anoscopy can often provide the correct diagnosis.2 This article focuses on common benign anorectal conditions (Table 12–15), but clinicians must keep in mind that benign and malignant diseases often present with similar symptoms.3

| Symptom | Differential diagnosis | Key points |

|---|---|---|

| Anal bleeding | Anal fissures Anal polyps Hemorrhoids Upper or lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding | Hemorrhoids are the most common cause and often resolve with fiber supplementation; grade III and IV hemorrhoids are more likely to benefit from surgical therapies Evaluate for malignancy in patients 50 years and older who have not had screening per U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines2–4 |

| Incontinence | Fecal impaction Fistula Neurologic disease Rectal prolapse Sphincter defect | If etiology is unknown after history and examination, anal sphincter imaging may aid with the diagnosis; biofeedback is an effective treatment5,6 |

| Mass | Abscess Anal polyps Condyloma Hemorrhoids Pilonidal cysts Rectal prolapse | Topical therapies are often effective for condyloma, but patients with large condylomata or those not initially responsive to treatment should be referred for surgical removal7,8 |

| Pain | Abscess Anal fissures Fistula Proctalgia fugax Proctitis Rectal prolapse Thrombosed external hemorrhoids Unspecified functional rectal pain | Surgery is generally recommended for abscesses, fistulas, prolapse, and thrombosed hemorrhoids (within 72 hours of symptoms); anal fissures may benefit from conservative treatment in the first 12 months2,3,9–12 |

| Pruritus | Dermatologic condition Excessive hygiene External hemorrhoids Infection Medication Pruritus ani | Topical hydrocortisone can be effective for pruritus ani; skin biopsy should be considered for patients without a clear etiology13–15 |

Hemorrhoids

Bleeding is the most common anorectal presenting symptom in primary care.1 Although hemorrhoids are the most common benign condition that causes anal bleeding, clinicians should consider a workup for other causes such as malignancy, colitis, anal fissures, and angiodysplasias in patients with symptoms or risk factors suggesting those conditions, even if hemorrhoids are present. Screening for colon cancer should be considered for patients with a family history of colorectal cancer and those older than 50 years who are not current on recommended screening.2,4 Cancer screening can also be considered for symptomatic patients 40 to 49 years of age because of increasing rates of cancer in this age group.16

A comprehensive review of the anatomy, diagnostic approach, and treatment of hemorrhoids was previously published in American Family Physician.17 Treatment is briefly discussed here.

NONSURGICAL TREATMENT

In most cases, the initial treatment of hemorrhoids is nonsurgical2 (Table 23,18,19). Adequate intake of insoluble fiber (25 to 35 g per day) and water reduces bleeding and other symptoms; the goal should be to pass a daily soft stool without straining.18 Evidence also supports using sitz baths to treat hemorrhoids in pregnant women, and they may also be beneficial in other populations.20 Topical medications such as steroids, analgesics, and antiseptics are commonly used but lack supporting evidence. 2 A Cochrane review suggests that phlebotonics such as flavonoids (a supplement not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration) and calcium dobesilate (not available in the United States) may help with symptoms of itching, bleeding, or leakage.19

| Adequate insoluble fiber (25 to 35 g per day) and water intake (1.5 to 2 L per day) |

| Behavior modification: avoid straining and prolonged periods on toilet, limit fatty foods and alcohol, perineal hygiene, weight loss |

| Calcium dobesilate (not available in the United States) |

| Flavonoids (not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; examples include diosmin, micronized purified flavonoid fraction, and rutosides) |

| Sitz baths or warm water sprays |

| Stool softeners |

| Topical analgesics, antiseptics, steroids, or vasoactive agents |

SURGICAL TREATMENT

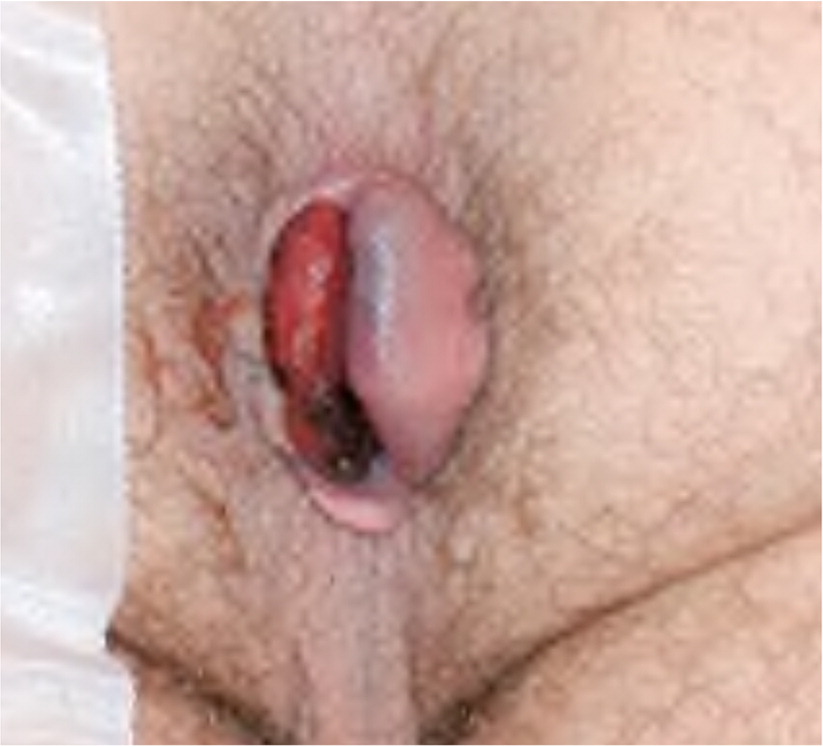

Table 3 describes surgical procedures used for treating hemorrhoids and other anal conditions, along with their success and complication rates.2,10,17,21–25 There are several indications for hemorrhoid surgery. One is surgical excision of painful thrombosed external hemorrhoids (Figure 126) that present within 72 hours of symptom onset. Surgical excision results in faster symptom resolution than conservative management or simple evacuation of the thrombus (3.9 days for excision vs. 24 days for conservative management). The recurrence rate at one year after excisional hemorrhoidectomy is 6.4% vs. 25.4% with conservative therapy.2,27

| Condition | Procedure | Description | Commonly performed by family physicians? | Potential complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal fissures10,21 | Lateral internal sphincterotomy | Incision at the internal sphincter under anoscopy; effectiveness of 88% to 100%; remains effective for chronic fissures | No | Fecal incontinence (8% to 30%) |

| Fecal incontinence22 | Injection of bulking agents | Injection of several options such as dextranomer/hyaluronic acid gel; effectiveness of 52% at six and 36 months | No | Fecal impaction |

| Sphincteroplasty | Repair of defect in the sphincter muscle fibers; 85% initial improvement, but 86% to 90% of patients will have recurrence within five years | No | Fecal impaction, infection, outlet obstruction | |

| Fistula23,24 | Endoanal advancement flap | Initial curettage of the fistula tract and closure with proximal mucosal flap; 66% to 87% initial healing rate | No | Incontinence (35%) |

| Endoscopic ablation | Cautery of the sinus tract under endoscopy with closure of the internal opening; 68% to 84% healing rate | No | Infection, drainage; no increased risk of incontinence | |

| Fistulectomy | Simple removal of the fistula tract with mucosal closure; 90% healing rate | No | Incontinence (28% to 42%), rectovaginal fistula | |

| Hemorrhoids2,17 | Excision of throm-bosed external hemorrhoid | Excision of thrombosed hemorrhoid under local anesthesia; decreases time to symptom resolution to 3.9 days vs. 24 days with conservative management | Yes | Bleeding, initial increased pain |

| Hemorrhoid artery ligation | Endoanal ultrasonography is used to identify and then ligate the hemorrhoidal artery; 3% to 60% recurrence rate | No | Increased pain and urinary retention compared with rubber band ligation | |

| Hemorrhoidectomy | Open or closed hemorrhoidectomy, encompassing multiple techniques; 14% recurrence rate at one year | No | Bleeding (1% to 2%), urinary retention (1% to 15%) | |

| Infrared coagulation | Directed infrared waves cause necrosis of a hemorrhoid; effectiveness of 81% with 28% recurrence rate at six months | No | Bleeding and discharge (13%) | |

| Rubber band ligation | Application (in the office) of a rubber band around base of hemorrhoid to cause necrosis; effectiveness of 93% but recurrence rate of 11% to 49% at one year | No | Bleeding (2.9%) | |

| Sclerotherapy | Injection of sclerosing agent (e.g., 5% phenol) into hemorrhoid; effectiveness of 20% to 88% | No | Mucosal ulceration, transient bacteremia (8%) | |

| Stapled hemorrhoidopexy | Circular stapling device that creates an anastomosis across a hemorrhoid; 32% recurrence rate at one year and increased complications | No | 16.1% total complication rate; rectal perforation, rectovaginal fistula | |

| Rectal prolapse25 | Multiple approaches | Transabdominal and perineal approaches with anchoring of the rectum using sutures with or without mesh; 3% to 29% recurrence rate | No | Anastomotic leak, large bowel obstruction, mesh erosion, ureteral injury, rectovaginal fistula |

Referral for surgery should also be considered for grade I, II, and smaller grade III hemorrhoids that are not responsive to conservative measures over six weeks. Rubber band ligation is more effective than injection sclerotherapy or infrared coagulation for these hemorrhoids.2 These office-based procedures are well tolerated but have higher recurrence rates than other surgical procedures.28

Excisional hemorrhoidectomy is the most effective surgical treatment for grade III and IV hemorrhoids, but it has higher rates of postoperative pain and longer recovery time than transanal hemorrhoid artery ligation and stapled hemorrhoidopexy.29,30 Randomized trials have found that topical diltiazem or topical baclofen decreases pain after hemorrhoid surgery.31,32

Perianal Pruritus

Perianal pruritus is the second most common anorectal symptom and has many possible causes.1 Although it is typically idiopathic, secondary causes (Table 413,14) must be ruled out because infections, inflammatory conditions, neoplasms, and irritant dermatitis can cause perianal pruritus. Pinworm infections are common in school-aged children, institutionalized adults, and their caregivers. Other infectious etiologies include herpes, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.13 Hemorrhoids and anal fissures also cause perianal pruritus, as do common dermatologic disorders such as lichen planus, contact dermatitis, and irritant dermatitis. Lumbosacral radiculopathy is a possible cause in patients with chronic back pain.

| Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

| Anorectal | Constipation, fissure, hemorrhoids, incontinence, inflammatory bowel disease, prolapse, skin tags |

| Dermatologic | Atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, irritant dermatitis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosis, malignancy (e.g., Bowen disease, Paget disease, squamous cell carcinoma), psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis |

| Infection | Candida, Corynebacterium, molluscum contagiosum, parasites (e.g., enterobiasis [pinworm], scabies), sexually transmitted infection (e.g., condyloma, herpes, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia), Staphylococcus aureus |

| Medication | Chemotherapy, colchicine, neomycin, quinidine |

| Systemic | Diabetes mellitus, leukemia, lymphoma, thyroid disease |

| Other | Dietary irritants (e.g., beer, citrus fruit, coffee, dairy, spicy foods, tomatoes), excessive cleaning, lumbosacral radiculopathy, psychological conditions |

Although the history and physical examination, including anoscopy, are usually adequate to determine a secondary cause, bacterial culture of the anal area and a punch biopsy that includes affected skin and adjacent normal skin may be necessary when the diagnosis is unclear or when initial therapy is ineffective.13 Testing for herpes, gonorrhea, and chlamydia should be considered for patients who participate in receptive anal intercourse.

Effective treatment of perianal pruritus requires treating the underlying cause, if identified, and restoring the normal barrier function of the anal and perianal skin. Proper hygiene is important and involves rinsing the area with water before drying and avoiding application of other chemical products, such as fragrances, cleansers, or hygienic wipes, which may worsen irritant dermatitis. A barrier emollient such as petroleum jelly should be used to protect the area from further irritation, and loosely fitted cotton clothing can help keep the area dry.14

Although several medical therapies have evidence for treating perianal pruritus, there are no good comparisons to determine which is the most effective. Bedtime oral sedating antihistamines may prevent nocturnal scratching, but they should be avoided in older adults because of their anticholinergic properties. Low-dose topical steroids such as hydrocortisone 1% ointment reduce perianal pruritus, but they should be used for only one to two weeks to prevent tissue atrophy.15 Other effective treatments include topical capsaicin 0.006% (which requires compounding) and tacrolimus 0.1% (Protopic).33,34

Anal Fissures

Anal fissures typically present with pain and/or bleeding after defecation. Examination will show a tear of the anal mucosa from the dentate line to the anal verge, most commonly in the posterior midline (Figure 2).26 Chronic anal fissures (lasting more than eight weeks) manifest findings such as a hypertrophied anal papilla, a sentinel tag, or exposed sphincter muscle, in addition to the fissure itself. Multiple fissures or those located lateral to the midline should raise suspicion for Crohn disease, and colonoscopy is warranted. If an internal rectal examination is necessary, it should be performed under sedation to avoid pain. Treatment of anal fissures involves restoring normal bowel and anal sphincter function. Acute fissures should be managed initially with sufficient fiber and fluid intake to achieve the passage of a daily soft stool without straining.9 Sitz baths may help keep the area clean and dry.10

Topical nitroglycerin 0.4% ointment, topical calcium channel blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections are effective for chronic anal fissures of less than one year’s duration.21,35 The topical calcium channel blockers diltiazem and nifedipine are more effective than topical nitroglycerin and are less likely to cause headaches; they should be used for initial therapy.36 Although these topical agents are available only through compounding pharmacies, they are preferred over oral calcium channel blockers because they have fewer adverse effects.37

Functional Rectal Pain

| Levator ani syndrome must include all of the following: Chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching Episodes last 30 minutes or longer Tenderness during traction on the puborectalis muscle (pain with posterior traction during rectal examination) Exclusion of other causes of rectal pain (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, intramuscular abscess and fissure, thrombosed hemorrhoids, prostatitis, coccygodynia, major structural alterations of the pelvic floor) |

| Proctalgia fugax must include all of the following: Recurrent episodes of pain localized to the rectum and unrelated to defecation Episodes last from seconds to minutes, with a maximum duration of 30 minutes No anorectal pain between episodes Exclusion of other causes of rectal pain (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, intramuscular abscess and fissure, thrombosed hemorrhoids, prostatitis, coccygodynia, major structural alterations of the pelvic floor) |

| Unspecified functional anorectal pain consists of the following: Chronic or recurrent episodic rectal pain that lasts more than 30 minutes Absence of tenderness during traction on the puborectalis muscle Exclusion of other causes of rectal pain (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, intramuscular abscess and fissure, thrombosed hemorrhoids, prostatitis, coccygodynia, major structural alterations of the pelvic floor) |

Levator ani syndrome is characterized by tenderness with traction on the puborectalis muscle. Proctalgia fugax is characterized by episodes of sharp pain lasting seconds to minutes. Unspecified functional anorectal pain, formerly known as chronic proctalgia, is characterized by pain lasting longer than 30 minutes and may be accompanied by disordered defecation.

Initial therapies for functional rectal pain include warm baths and fiber supplementation. Inhaled salbutamol (not available in the United States) is an effective treatment for proctalgia fugax.44 Biofeedback is also beneficial for pain and defecatory issues in all functional rectal pain syndromes and should be considered in patients who do not respond to the above treatments within one to two months.43,45 Additional treatment options include topical diltiazem, topical glyceryl trinitrate, and tricyclic antidepressants; however, tricyclics should generally be avoided in older adults because of their anticholinergic effects.45 Evidence supports the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA injections for proctalgia fugax.45

Perianal Abscess

A sensation of a mass in the anal area may be due to an abscess, hemorrhoids, condylomata, rectal prolapse, anal polyps, or anorectal cancer. Perianal abscesses commonly present with painful swelling in the rectal area.46 Examination typically reveals erythema, pain, and induration. The physical examination should focus on determining abscess size and anal sphincter involvement. An opening with or without active drainage suggests fistula formation.

Incision and drainage is the preferred treatment for perianal abscess.11 Family physicians should drain superficial abscesses that do not involve the anal sphincter in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia with epinephrine. Packing should be avoided because it likely increases pain and may delay wound healing.23 Abscesses involving the anal sphincter, fistulas, or other deeper structures should be drained in the operating room to ensure adequate drainage and preserve the anal sphincter.23 Although antibiotics have not generally been used in the absence of cellulitis or sepsis,47 a recent study suggests that routine antibiotic administration should be considered after incision and drainage because it results in a lower rate of fistula formation (odds ratio = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.96; P = .03).48 Abscesses should be followed postoperatively until healed to ensure resolution.

If the abscess fails to resolve or recurs after resolution, the patient should be evaluated for fistula tracts. Although the physical examination is often sufficient for identifying a fistula, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or endoanal ultrasonography can better define the anatomy in cases of recurrent disease or if there is suspicion for occult fistula. Magnetic resonance imaging and endoanal ultrasonography both have sensitivities of 87%, but specificity is 69% and 43%, respectively.23 Therefore, magnetic resonance imaging is generally recommended, although computed tomography can be used if other modalities are not available.

If a fistula is present, surgical fistulectomy is the preferred treatment and can be performed concomitantly with abscess drainage.23 Recurrent perianal abscesses or fistulas warrant further investigation, including evaluation for Crohn disease and HIV infection.

Condyloma

Anogenital warts should be treated with patient- or clinician-applied topical medications and/or surgical or destructive techniques. Examples of patient-applied therapies include imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara), podofilox 0.5% solution (Condylox), and sinecatechins 15% ointment (Veregen). Clinician-applied therapies include podophyllin and trichloroacetic acid. Destructive techniques include cryosurgery, electrosurgery, and surgical excision. Current evidence does not support one treatment over another.8 Treatment decisions should be guided by patient preferences, risk of harm, and physician experience.

Condylomata are a risk factor for anorectal cancer.51 There are currently no evidence-based guidelines for anal cancer screening in patients with these lesions. However, many experts recommend annual screening with digital rectal examinations and anal Papanicolaou smears for patients with HIV infection, men who have sex with men, women with a history of vulvar or cervical cancer, and transplant recipients.52–55

Rectal Prolapse

Rectal prolapse is a full-thickness intussusception of the bowel through the anus. It often presents as a mass protruding through the anus after straining (Figure 4).26 Other symptoms may include anal discharge, pain, and bleeding. The condition is most common in women, and its prevalence increases with age.25 Treatment of rectal prolapse is surgical, although a Cochrane review found no single surgical procedure to be superior.12

Fecal Incontinence

Fecal incontinence is recurrent uncontrolled passage of fecal material. It occurs in 5.9% of adults, but less than 50% of patients inform clinicians about the problem, even after direct questioning.56 The rate of fecal incontinence is considerably higher in care homes, ranging from 30% to 50%.57 There is evidence that adequate fiber intake decreases the incidence of fecal incontinence in women.58

Common causes of fecal incontinence include anal sphincter defects, impaction with overflow, neuropathy, rectal prolapse, and inflammatory bowel disease. Central nervous system disorders can also cause fecal incontinence, and incontinence from sphincter defects caused by obstetric or surgical procedures can present decades after the injury.59 With so many possible contributing causes, fecal incontinence is often multifactorial, so a history with a focus on identifying reversible causes is the first step. A focused physical examination should include an external examination with straining to evaluate for prolapse, a digital rectal examination to assess anal tone and check for impaction, and an assessment of neurologic function using a perianal pinprick test for sensation. Pinprick testing is accomplished by touching a sharp instrument to the edge of the anal verge and verifying the patient’s sensation. An anal wink consisting of involuntary contraction of the anal sphincter can concomitantly be observed to confirm an intact sacral reflex arc. If no cause is apparent, the next step is anorectal manometry, in which a balloon catheter is placed inside the rectum to measure function of the anal sphincter during rest, contraction, and simulated defecation.3,22

Initial treatment of fecal incontinence involves correcting the underlying cause, if possible. Fecal incontinence due to diarrhea should be treated with antidiarrheal agents,2,22,60 and impaction with overflow incontinence should be treated by medical or manual disimpaction. Multiple randomized controlled studies have shown that biofeedback is also effective for fecal incontinence, and it is considered a first-line treatment.5 Other treatments include fiber supplementation, fluid management, and diet and stool diaries to help guide dietary management.61 Barrier ointments such as zinc oxide and the use of pads are also helpful.60 In long-term care facilities, individualized care plans incorporating staff education, scheduled toileting, and conservative use of laxatives may reduce incontinence.60

If these treatments are ineffective, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging or endoanal ultrasonography should be considered to detect sphincter defects; if defects are present, patients should be referred for sphincteroplasty or anal bulking. Sphincteroplasty provides good short-term results, but incontinence returns in 86% to 90% of patients by five years.6 One randomized controlled trial studying the injection of anal bulking agents showed a 52% improvement in incontinence episodes, suggesting that this may be an effective treatment.62

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Fargo and Latimer,26 Pfenninger and Zainea,64 and Pfenninger and Zainea.65

Data Sources: PubMed, DynaMed, Essential Evidence Plus, TRIP, and the Cochrane database were searched for key terms regarding anorectal pathology. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Search dates: October 1, 2018, to July 29, 2019.