Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(7):419-428

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Most frequent headaches are typically migraine or tension-type headaches and are often exacerbated by medication overuse. Repeated headaches can induce central sensitization and transformation to chronic headaches that are intractable, are difficult to treat, and cause significant morbidity and costs. A complete history is essential to identify the most likely headache type, indications of serious secondary headaches, and significant comorbidities. A headache diary can document headache frequency, symptoms, initiating and exacerbating conditions, and treatment response over time. Neurologic assessment and physical examination focused on the head and neck are indicated in all patients. Although rare, serious underlying conditions must be excluded by the patient history, screening tools such as SNNOOP10, neurologic and physical examinations, and targeted imaging and other assessments. Medication overuse headache should be suspected in patients with frequent headaches. Medication history should include nonprescription analgesics and substances, including opiates, that may be obtained from others. Patients who overuse opiates, barbiturates, or benzodiazepines require slow tapering and possibly inpatient treatment to prevent acute withdrawal. Patients who overuse other agents can usually withdraw more quickly. Evidence is mixed on the role of medications such as topiramate for patients with medication overuse headache. For the underlying headache, an individualized evidence-based management plan incorporating pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies is necessary. Patients with frequent migraine, tension-type, and cluster headaches should be offered prophylactic therapy. A complete management plan includes addressing risk factors, headache triggers, and common comorbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes that can impair treatment effectiveness. Regular scheduled follow-up is important to monitor progress.

Patients with increasingly frequent headaches can develop disabling symptoms. Biochemical, metabolic, and other changes induced by frequent headaches and/or medication are thought to cause central sensitization and neuronal dysfunction that results in inappropriate response to innocuous stimuli, lowered thresholds to trigger pain response, exaggerated response to stimuli, and persistence of pain after removal of inciting factors.1–4 Together, these changes result in increasingly frequent—and often daily—headache and related symptoms. Each year, 3% to 4% of patients with episodic migraine or tension-type headaches (TTH) escalate to chronic forms.5,6

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not recommend prolonged or frequent use of over-the-counter pain medications for headache. | American Headache Society |

| Do not prescribe opioid or butalbital-containing medications as first-line treatment for recurrent headache disorders. | American Headache Society |

| Do not perform neuroimaging studies in patients with stable headaches that meet criteria for migraine. | American Headache Society |

| Do not perform computed tomography imaging for headache when magnetic resonance imaging is available, except in emergency settings. | American Headache Society |

An estimated 2% to 4% of U.S. adults have chronic headaches, and more than 30% of these report daily symptoms.6–8 Once central sensitization occurs, headaches are difficult to treat and cause substantial morbidity. The mean annual cost of chronic migraine (including lost productivity and medical care) is more than three times the cost of episodic migraine (approximately $8,250 vs. $2,650).9,10 This article aims to assist physicians in identifying patients at risk of escalating to chronic headache and presents an approach to preventing such escalation. Although the literature focuses on migraine, the approach is applicable to other types of headache.

Risk Factors for Escalation from Episodic to Chronic Headache

Identifying patients with risk factors for escalating from episodic to chronic headaches can help physicians and patients be alert for early signs of escalation and aware of the need to address modifiable risk factors, especially medications.

The strongest predictive factors for headache progression are frequent headache episodes at baseline and medication overuse11 (Table 12,7,8,11). Definitions of chronic migraine and TTH specify that symptoms be present on at least 15 days per month, but central sensitization may occur at lower frequencies.5 Migraine may have a threshold for central sensitization of four episodes per month.1,11 Symptoms predictive of migraine escalation are pulsating quality, severe pain, photophobia, phonophobia, and attacks lasting longer than 72 hours.12 Long attack duration and nausea are predictive of development of chronic TTH.13 Cutaneous allodynia is strongly associated with chronification and may be a marker of central sensitization.13,14 The highest medication-associated risk is with opioids, followed by triptans, ergotamines, and nonopioid analgesics.7,11

| Risk factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Headache days per month* | — | |

| 0 to 4 | 1.00 (referent) | |

| 5 to 9 | 7.6 (2.2 to 26.1); P = .001 | |

| 10 to 15 | 25.4 (7.6 to 84.5); P = .001 | |

| Medication overuse* † | — | |

| Opioids | 4.4 (0.3 to 59.7) | |

| Triptans | 3.7 (0.8 to 16.4) | |

| Ergotamines | 2.9 (0.4 to 23.0) | |

| Analgesics | 2.7 (0.6 to 11.7) | |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg per m2) | 5.53 (1.4 to 21.8) | May explain other associations (e.g., sleep disorders) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.34 (0.96 to 12.3); P = .059 | Not significant after adjusting for BMI and baseline headache frequency |

| Arthritis | 3.29 (1.03 to 10.5); P < .05 | Not significant after adjusting for BMI and baseline headache frequency |

| Head or neck injury | Males: 3.3 (1.0 to 19.8) Females: 2.4 (1.0 to 10.8) | No relationship with severity or time since injury |

Chronic pain, especially musculoskeletal pain, and obesity are strongly associated with chronification.15 Associations with snoring, sleep disorders, diabetes mellitus, and arthritis lose significance when controlling for body mass index and headache frequency.11 Several psychiatric conditions (e.g., major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, anxiety) are associated with headache frequency and disability. It is unclear if these are risk factors or comorbidities, or if they share etiologies with chronic headaches. 6,16 Stressful life events are associated with increasing headache frequency, especially in middle age.17

Approach to the Patient with Frequent Headaches

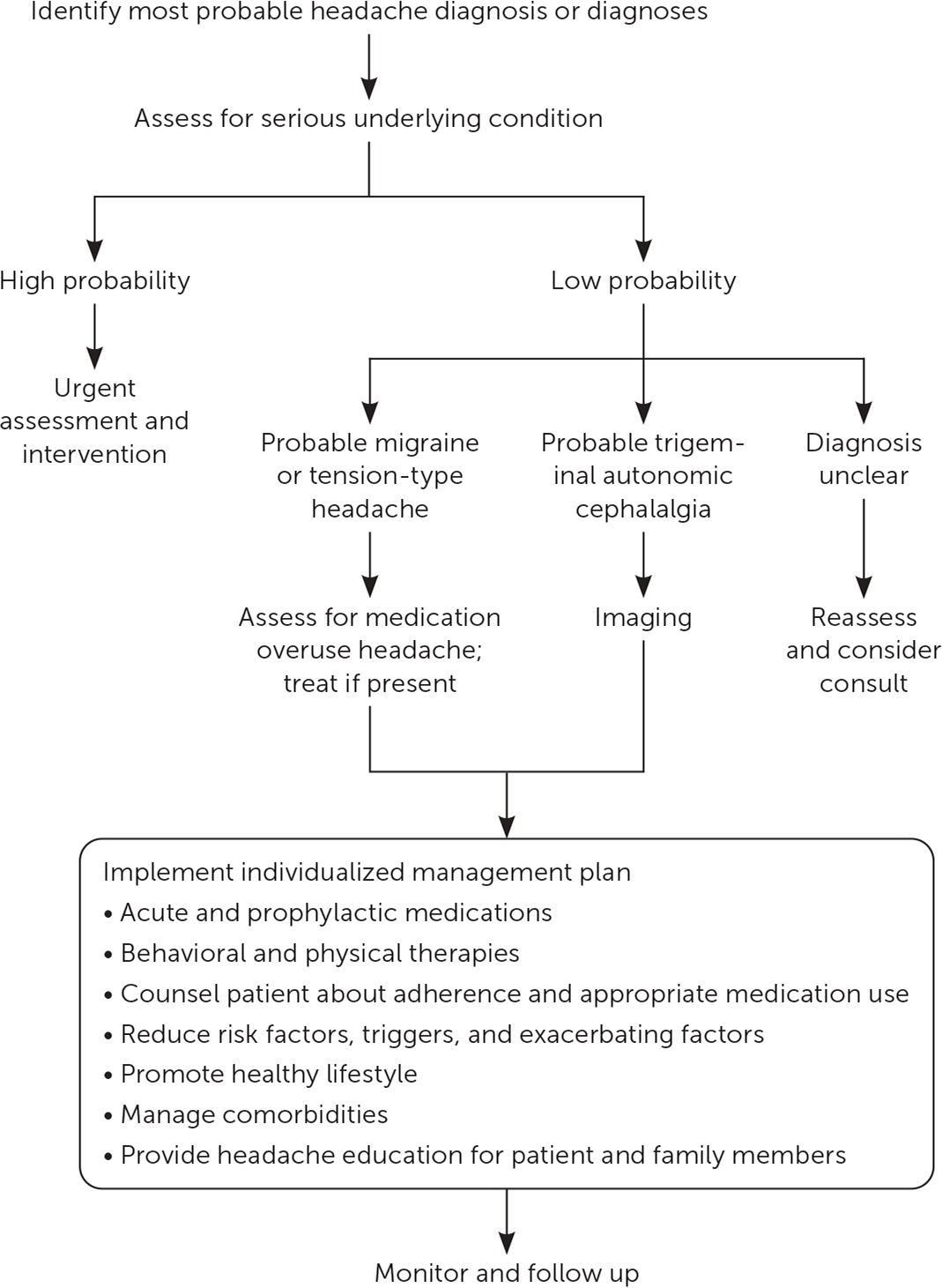

An algorithm for the evaluation of patients with frequent headaches is presented in Figure 1.

Clarify Headache Type and Pattern

A full assessment to clarify headache frequency, type, and severity takes time, but it is an investment in successful management and may avoid multiple patient visits and requests for medication (Table 2).18–21 Every effort should be made to accurately diagnose each headache using criteria from the International Headache Society (eTable A, eTable B, eTable C, eTable D, and eTable E) that define different primary (e.g., migraine, TTH, cluster headaches) and secondary headaches (e.g., those due to trauma, vascular malformations, infection, or cerebrospinal fluid pressure disorders). Individual patients may not completely match criteria for a specific headache diagnosis and may have more than one type of headache.5 The POUND mnemonic can be useful in the diagnosis of migraine22,23 (Table 322).

| Headache history |

| Associated symptoms (especially nausea, vomiting, fatigue, photo- or phonophobia, head or neck tenderness, autonomic symptoms, or allodynia) |

| Beliefs about cause, appropriate management, and prognosis; goals for management |

| Coping mechanism, effects on quality of life, and support system |

| Duration of episodes |

| Exacerbating and relieving factors (e.g., activity, light and noise avoidance, sleep) |

| Frequency of episodes and change in pattern |

| Intensity of pain (1 to 10 scale) |

| Medications used and effectiveness (name and dosage for all prescription and nonprescription medications) |

| Pain location |

| Pattern and rate of onset, peaking, and resolution of symptoms |

| Precipitating or associated events (triggers, prodromes) |

| Previous assessments, diagnoses, and treatments |

| Quality of pain (e.g. throbbing, pulsating, squeezing, splitting) |

| Additional history |

| Evidence of common comorbidities (e.g., depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance or alcohol misuse, chronic pain) |

| Risk factors for conversion to chronic headache (Table 1) |

| Signs or symptoms of serious secondary headache (Table 4) |

| Physical examination |

| General impression, vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature) |

| Head: temporal artery firmness/tenderness (in older patients), sinus tenderness |

| Neck: posture, range of motion, muscle tenderness |

| Neurologic: general assessment of mental status; cranial nerve examination, including fundoscopy; pupils; eye movements; visual fields; facial power and sensation; soft palate and tongue movements; limb power; tone; coordination; reflexes; gait, including heel-toe walking (tandem gait); plantar responses |

| Other assessments as indicated by symptoms, medical history, or risk factors |

| Diagnostic testing |

| Imaging: not recommended unless patient has red flag symptoms (Table 4), trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, or atypical headache, or to diagnose specific suspected underlying disorder |

| Laboratory testing as indicated to identify underlying condition in patients with secondary headache (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate for temporal arteritis) |

| Other assessments |

| Headache diaries |

| Measures of headache effects and disability (e.g., Headache Impact Test* ) to assess quality of life and track progress |

| Screening tools for comorbidities (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression†, CAGE questionnaire for alcohol use‡) |

Acute (episodic)

|

Chronic

|

Infrequent episodic

|

| Frequent episodic |

| At least 10 episodes occurring on 1 to 14 days per month on average for > 3 months (≥ 12 and < 180 days per year) and fulfilling criteria B to E for infrequent episodic tension-type headache |

Chronic

|

| Cluster headache | Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache |

Episodic

Chronic

Paroxysmal hemicrania Episodic

Chronic

| Episodic

Chronic

Hemicrania continua Remitting

Unremitting

|

Primary cough headache

| External-pressure headache

|

Primary exercise headache

| Primary stabbing headache

|

Primary headache associated with sexual activity

| Nummular headache

|

Primary thunderclap headache

| Hypnic headache

|

Cold-stimulus headache

| New daily persistent headache

|

General definition

|

| Diagnostic categories |

| Headache attributed to: |

| Cranial and/or cervical vascular disorder (e.g., cerebral ischemia, hemorrhage, thrombosis, arteritis, vascular malformations, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, carotid and vertebral artery conditions) |

| Disorder of homeostasis (e.g., hypoxia, hypercapnia, hypertension, fasting, dialysis, hypothyroidism, cardiac conditions) |

| Disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cranial structure (e.g., glaucoma, sinus conditions, cervical radiculopathy, temporomandibular disorder) Infection (e.g., acute and nonacute intracranial and systemic infections) |

| Nonvascular intracranial disorder (e.g., increased or decreased cerebrospinal fluid pressure, inflammatory conditions, neoplasia, seizure, type 1 Chiari malformation) |

| Psychiatric disorder (e.g., somatization or psychotic disorder) |

| Trauma or injury to the head and/or neck (e.g., acute or persistent headaches related to injury or trauma) |

| Use of or withdrawal from a substance (e.g., carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, histamine, alcohol, cocaine) |

| Pulsating or throbbing pain |

| One-day average duration |

| Unilateral location |

| Nausea or vomiting |

| Disabling |

History. As headaches become more frequent, patients often have difficulty recalling details. A headache diary can help document date, duration, symptoms, treatment, and outcome of each headache episode, in addition to suspected triggers or other patient observations.18–21,24,25 Patients with migraine are often hyperresponsive to causes of secondary headaches.5 A diary may identify an overlooked cause of secondary headaches or a recurrent trigger for migraine episodes.

The history should cover the patient's typical headaches as well as recent changes. The current headache diagnosis may be inaccurate, incomplete, or undergoing transition. In studies, migraine was the correct diagnosis in 82% of patients previously diagnosed with nonmigraine headaches and in 88% of patients diagnosed with sinus headaches.26,27 Patients often describe more than one type of headache. More than 80% of those with confirmed migraine also have TTH, and patients with any primary headache may develop superimposed secondary headaches.28

The history may detect symptoms of progression to chronic headache. Patients who develop chronic migraine typically report progressively frequent bilateral frontotemporal TTH-type symptoms with superimposed full-blown migraine attacks. Sleep and emotional disturbances are common. 12,29 Patients developing chronic TTH or medication overuse headaches (MOH) often have nonspecific headaches.

Physical Examination. Between headache episodes, physical examination is usually normal in patients with frequent migraine, TTH, and other primary headaches. Guidelines recommend neurologic assessment and physical examination of the head and neck, focusing on any potential source of secondary headaches (Table 2).18–21

Imaging. Guidelines recommend magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast in patients with trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (e.g., cluster headache, paroxysmal hemicrania, hemicrania continua, short-lasting neuralgiform headache), headaches with new features or neurologic deficits, or suspected intracranial abnormality.30–32 The American College of Radiology recommendations can help guide imaging for various headache presentations, headaches in specific locations (e.g., base of skull, orbit, sinuses), and investigation of specific conditions, and imaging in older adults, pregnant women, and patients with cancer or other immunocompromising condition.32

Decisions about imaging in patients with increasingly frequent migraine or TTH are challenging.18–21,24,30–32 U.S. headache guidelines recommend magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast for patients with progressively worsening headaches over weeks to months because of the remote possibility of subdural hematoma, hydrocephalus, tumor, or another progressive intracranial lesion.18 Nevertheless, without neurologic findings, relevant results from neuroimaging are reported in less than 1% of patients who have frequent episodic migraine.23 Other imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, electroencephalography, and transcranial Doppler ultrasonography are not recommended in patients with frequent headaches.31

RULE OUT SERIOUS UNDERLYING CONDITIONS

Serious pathologic conditions are uncommon causes of frequent headaches, but they must be considered, even in patients with confirmed primary headaches. Expert groups list different red flag warning features. The SNNOOP10 mnemonic describes symptoms that should raise suspicion for serious underlying pathology in patients with headache (Table 4).33 The probability of a significant lesion is most strongly associated with cluster-type headache symptoms, abnormal neurologic examination, poorly defined headache, and headaches associated with aura, the Valsalva maneuver, or exertion.23

| Sign or symptom | Potential cause of headache |

|---|---|

| Systemic symptoms (e.g., fever, rash, myalgia, weight loss) | Intracranial infection or nonvascular condition; carcinoid tumor, pheochromocytoma |

| Neoplasm diagnosis (current or history) | Brain neoplasm or metastasis |

| Neurologic deficit or dysfunction (e.g., focal deficits, seizure, cognitive or consciousness changes) | Intracranial disorder |

| Onset sudden or abrupt* | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, cranial or cervical vascular lesion |

| Older age (> 50 years) | Giant cell arteritis, cervical or intra-cranial lesions |

| Painful eye plus autonomic features | Posterior fossa; pituitary, cavernous sinus, or ophthalmic condition; Tolosa-Hunt syndrome |

| Painkiller overuse or new medication | Medication overuse headache, medication adverse effect or incompatibility |

| Papilledema | Intracranial condition, intracranial hypertension |

| Pathology of immune system | HIV or opportunistic infection |

| Pattern: new headache or change in pattern of established headache | Intracranial condition |

| Position exacerbates or relieves pain | Intracranial hypotension or hypertension |

| Posttraumatic onset (acute or chronic) | Subdural hematoma, vascular condition |

| Precipitated by sneezing, coughing, or exercise | Posterior fossa or Arnold-Chiari malformation |

| Pregnancy or puerperium | Cranial or cervical vascular condition, hypertension/preeclampsia, cerebral sinus thrombosis, epidural-related headache |

| Progressive and atypical presentation | Nonvascular intracranial condition |

ASSESS FOR MEDICATION OVERUSE

Addressing medication overuse may be the most important intervention for increasingly frequent headaches.18–21,34 About 30% to 50% of patients who develop chronic headaches have MOH,6,8,35,36 which is defined as headache on 15 or more days per month in a patient with preexisting primary headache, developing as a consequence of regular overuse of acute or symptomatic headache medication for more than three months.5 Overuse is defined as 15 or more days per month for nonopiate analgesics and 10 or more days per month for ergotamines, triptans, opioids, and combinations of drugs from more than one class.5 MOH usually resolves after stopping overuse, but this is no longer required for diagnosis.5 MOH develops almost exclusively in patients with migraine or TTH. Nonopioid analgesics are the most commonly implicated medications because of their widespread use in headache treatment; however, triptans are an increasingly common cause of MOH in the United States. The estimated mean critical dose and duration of use for triptans are 18 doses per month and 1.7 years, compared with 114 doses per month and 4.8 years for simple analgesics.37 Although not recommended and less commonly used for headache, opioids present the greatest risk of MOH and the most difficult type to treat.35,36

MOH has no classic features. Symptoms vary among patients and over time. Patients often describe insidious onset of increasingly frequent headaches on awakening or early in the day. Headaches are of variable quality, intensity, and location. Neck pain is common, and autonomic and vasomotor symptoms such as rhinorrhea, nasal stuffiness, and vasomotor instability are reported.35,36 Patients with MOH often have sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. These disorders usually predate MOH and may contribute to the progression to chronic headaches.35,36,38 Diagnosing MOH depends on an accurate and detailed medication history. Patients may underestimate their use of nonprescription analgesics or be unwilling to disclose opiate use. Screening with the questions “Do you take a treatment for attacks more than 10 days per month?” and “Is this intake on a regular basis?” is reported to be 95.2% sensitive and 80% specific for MOH in patients with frequent migraines.39 The single-question drug screen (“How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for nonmedical reasons?”) is reported to be 100% sensitive and 74% specific for detection of a drug use disorder in the family medicine setting.34

The optimal strategy for medication withdrawal is unclear. Guidelines stress that treatment should be individualized, incorporating patient education, supportive resources, and nonpharmacologic therapies, especially in patients with associated stress and chronic pain conditions. Patient education is crucial.18–20,35 In one study, 76% of patients with MOH were no longer overusing medications and 42% no longer had chronic headache 18 months after being provided information but no other specific treatment.40 Evidence on the effectiveness of abrupt vs. tapered withdrawal is inconsistent.41–43 Rapid outpatient withdrawal is generally recommended for nonopioid analgesics (including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and aspirin), ergotamines, and triptans. Inpatient tapered withdrawal is recommended for patients taking opiates, barbiturates, or benzodiazepines; those with significant comorbidities; and those in whom previous outpatient withdrawal was ineffective.18–20,35,41 Recommendations about pharmacologic treatment for MOH are limited by study quality, limited follow-up, poor compliance with study medications, and difficulty controlling for other factors in treatment, especially patient education and support during withdrawal.35,42,43 All studies have been conducted on patients with MOH and chronic migraine; no guidelines are available for other patients with MOH. European guidelines state that topiramate (Topamax), 100 to 200 mg per day, is probably effective in MOH, and that corticosteroids (at least 60 mg per day) and amitriptyline (up to 50 mg per day) are possibly effective.41 A 2019 review found two studies reporting significant therapeutic advantage over placebo for topiramate, and one study each for onabotulinumtoxin A (Botox) and valproate (Depacon).35

In about 75% of patients with MOH, discontinuing the overused medication results in reversion to episodic migraine or TTH; however, the relapse rate is about 30% per year.41 Effective treatment for the underlying headache and close follow-up are essential to prevent the patient from reverting to MOH.

DEVELOP A HEADACHE MANAGEMENT PLAN

Achieving prolonged symptom-free periods may be initially unrealistic, but progress in breaking the escalating pattern of frequent headaches enables the patient and physician to focus on developing the most effective plan to manage episodic headaches and prevent recurrent escalation. Before initiating a management plan, the clinical features should be reviewed to verify the probable headache diagnosis, confirm the absence of significant underlying conditions, and identify comorbidities that could complicate management. Consultation with a neurologist is recommended if a primary headache diagnosis cannot be confirmed, red flag symptoms are detected, or headaches do not improve with appropriate treatment.18

Patients with frequent headaches require both prophylactic and acute pharmacologic treatment.18–21 Evidence-based reviews and guidelines provide a basis for selecting medications for individual patients (Table 5).20,44–53 Considerations include effectiveness, pharmacokinetics, medical history, coexisting conditions, adherence, tolerance of adverse effects, cost and insurance considerations, and patient beliefs about the selected agent.21 Patients with a history of MOH with one agent should be prescribed an alternative agent with a lower risk of overuse. Coexisting conditions, especially depression and anxiety, may impair adherence and are associated with poorer outcomes. Medications for headache prophylaxis may be helpful in treating comorbid conditions (e.g., amitriptyline for depression or chronic pain, propranolol for hypertension).

| Headache type | Acute treatments | Chemoprophylaxis* |

|---|---|---|

| Migraine | Acetaminophen, 1,000 mg | Amitriptyline, 10 to 150 mg at bedtime |

| Acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine, 500 mg/500 mg/130 mg | Atenolol, 50 to 200 mg daily | |

| Almotriptan, 12.5 mg | Candesartan (Atacand), 16 mg daily | |

| Aspirin, 900 to 1,000 mg | Divalproex (Depakote), 250 to 750 mg twice daily | |

| Eletriptan (Relpax), 20 to 80 mg | ||

| Frovatriptan (Frova), 2.5 mg | Metoprolol, 50 to 100 mg twice daily | |

| Ibuprofen, 200 to 400 mg | ||

| Naproxen, 500 to 825 mg | Nadolol (Corgard), 80 to 160 mg daily | |

| Naratriptan (Amerge), 1 to 2.5 mg | Nortriptyline (Pamelor), 10 to | |

| Rizatriptan (Maxalt), 5 to 10 mg | 100 mg at bedtime | |

| Sumatriptan (Imitrex), 25 to 100 mg orally, 10 to 20 mg intranasally, or 4 to 6 mg subcutaneously | Propranolol, 40 to 160 mg twice daily | |

| Sumatriptan/naproxen (Treximet), 85 mg/500 mg | Topiramate (Topamax), 25 to 200 mg daily | |

| Zolmitriptan (Zomig), 2.5 mg orally or 2.5 to 5 mg intranasally | Valproate (Depacon), 400 to 1,500 mg daily | |

| Tension | Acetaminophen, 1,000 mg | Amitriptyline, 10 to 75 mg at bedtime |

| Aspirin, 500 to 1,000 mg | Nortriptyline, 10 to 100 mg at bedtime | |

| Diclofenac, 12.5 to 25 mg | ||

| Ibuprofen, 200 to 800 mg | ||

| Ketoprofen, 25 mg | ||

| Naproxen, 375 to 550 mg | ||

| Cluster | Oxygen 100%, 7 to 12 L per minute for 15 minutes | Civamide (not available in the United States), 100 mcg intranasally |

| Sumatriptan, 6 mg subcutaneously | Lithium, 900 to 1,200 mg daily | |

| Zolmitriptan, 5 mg intranasally | ||

| Verapamil, 240 to 960 mg daily | ||

| Rare primary headaches | May respond to indomethacin | — |

Guidelines stress that behavioral and physical therapies should be integrated with pharmacologic treatment of frequent headaches, but patient access may be limited, and evidence-based guidance is sparse.18–20,53 For migraine, relaxation training with or without thermal biofeedback, electromyographic biofeedback, and cognitive behavior therapy were strongly recommended by the U.S. Headache Consortium based on evidence from consistent findings in randomized controlled trials.53 Other guidelines recommend stress management and acupuncture. European guidelines for TTH recommend electromyographic biofeedback based on a meta-analysis of 53 studies.47 Cognitive behavior therapy, relaxation training, physical therapy, and acupuncture were given lower-grade recommendations because of lack of conclusive evidence of effectiveness.47 Patient adherence is a major barrier to behavioral treatments. Key factors in adherence are negative attitudes and beliefs, lack of motivation, poor awareness of triggers, external locus of control, poor self-efficacy, low levels of pain acceptance, and maladaptive coping styles.54 Self-management interventions such as cognitive behavior therapy, mindfulness, and education are more effective than usual care in reducing pain intensity, mood- and headache-related disability, but they may not reduce the frequency of migraine or TTH.55

Guidelines stress addressing the role of lifestyle issues such as poor sleep, lack of exercise, smoking, obesity, and caffeine use in triggering and exacerbating headaches, but the impact of these factors has not been quantified.

ENSURE FOLLOW-UP

Regularly scheduled follow-up is necessary to monitor the patient's headache pattern and make adjustments to the management plan. Patients should be instructed to report signs of reescalation of primary headaches, development of MOH, or red flags for developing serious secondary headaches. Factors associated with recurrent escalation of episodic headache are not clear, but poor prognosis in patients with chronic headache is associated with psychosocial factors, anxiety, mood disorders, poor sleep, stress, and low headache management self-efficacy. Based on lower-quality studies, other factors such as higher patient expectations, older age, older age at onset, headache frequency and intensity, BMI, disability scores, and unemployment are inconsistently predictive of treatment response.56

Several innovative medications are becoming available for prevention and acute treatment of migraine but have not yet been incorporated into evidence-based guidelines. Although these are valuable additions to migraine treatment, it is important to reconsider the diagnosis, screen for MOH, and address factors that could be driving headache escalation before prescribing new and expensive agents. The current expert consensus supports the use of small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (ubrogepant [Ubrelvy] and rimegepant [Nurtec], both of which were recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration) and the selective 5-hydroxy tryptamine receptor 1F agonist lasmiditan (Reyvow) for treatment of acute migraine in patients who have documented nonresponse to or intolerance of at least two oral triptans. Validated outcome questionnaires, such as the Migraine-Treatment Optimization Questionnaire, Migraine Assessment of Current Therapy, or Functional Impairment Scale, are recommended to document eligibility for therapy and to monitor outcomes.

Emerging treatments for migraine prophylaxis include monoclonal antibodies to the CGRP receptor (erenumab [Aimovig]) and CGRP ligands (fremanezumab [Ajovy], galcanezumab [Emgality], and eptinezumab). Other agents and oral forms are in development. Indications for use require confirmed diagnosis of frequent or chronic migraine plus inability to tolerate or inadequate response to an adequate trial of at least two prophylactic agents with established effectiveness, such as topiramate, metroprolol, divalproex (Depakote), or amitriptyline. After three to six months, therapy should be continued only if headache days per month have been reduced by 50% or significant improvement can be documented on a validated outcome measure, such as the Migraine Disability Assessment, the six-item Headache Impact Test, or the Migraine Physical Function Impact Diary.

Data Sources: Multiple PubMed searches were completed using the key words headache, frequent headache, and chronic headache. Information from Essential Evidence Plus was incorporated in literature searches. Guidelines and expert recommendations from the American Academy of Neurology, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, American Headache Society, U.S. Headache Consortium, and European Federation of Neurologic Societies were also searched. The bibliographies of relevant articles were reviewed to identify any primary sources missed in the original searches. Search dates: November 2018 and January 2019.

Editor's Note: Dr. Walling is an associate editor for American Family Physician.