Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(2):91-98

Related editorial: Closing Primary and Prenatal Care Gaps to Prevent Congenital Syphilis

Related letter: Broad Screening Is Needed for All Patients at Risk of Syphilis

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Rates of primary, secondary, and congenital syphilis are increasing in the United States, and reversing this trend requires renewed vigilance on the part of family physicians to assist public health agencies in the early detection of outbreaks. Prompt diagnosis of syphilis can be challenging, and not all infected patients have common manifestations, such as a genital chancre or exanthem. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for syphilis in all patients at increased risk, particularly those who reside in high-prevalence areas, sexually active people with HIV infection, and men who have sex with men. Other groups at increased risk include males 29 years or younger and people with a history of incarceration or sex work. All pregnant women should be screened for syphilis at the first prenatal visit, and those at increased risk should be screened throughout the pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the traditional screening algorithm for most U.S. populations. Penicillin is the preferred treatment across all stages of syphilis, although limited research suggests a possible role for other antibiotics in penicillin-allergic patients with primary or secondary syphilis. Pregnant women with syphilis who are allergic to penicillin should undergo penicillin desensitization before treatment.

Syphilis is a chronic bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. This disease has been known for hundreds of years, and its predictable clinical stages and well-established treatments made it a candidate for global eradication at several points during the 20th century. However, the incidence in the United States is currently increasing.1,2 Control efforts have been hindered by clinicians' lack of familiarity with clinical presentations, diagnosis, and treatment options. Additionally, the stigma associated with syphilis makes timely diagnosis and partner notification a challenge.

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

In the United States, rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased nearly every year since 2001, with the 35,063 cases reported in 2018 representing a 71% increase from 2014.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, more than 5 million new cases of syphilis are diagnosed each year, with most occurring in low- to middle-income countries.3,4 In the United States, rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased nearly every year since 2001, and the 35,063 cases reported in 2018 represented a 71% increase from 2014.2 Although the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis has increased in both sexes across all regions, men account for more than 90% of cases. Men who have sex with men account for 82% of cases in men.5 Syphilis is closely associated with HIV infection; genital ulcers in people with syphilis are densely infiltrated with lymphocytes and serve as sources of both entry and transmission of HIV.6 Congenital syphilis cases have more than doubled in recent years, reaching a 20-year high in 2017.7 This increase parallels rates in reproductive-aged women during the same period.

In the United States, syphilis tends to be transmitted within social networks, and 15% to 20% of diagnoses occur in people who have had the infection previously.8,9 This transmission pattern makes surveillance a challenge because pockets of outbreaks can occur while overall rates in the general population remain relatively constant.

Stages

The clinical course of untreated syphilis is that of chronic infection with highly variable clinical manifestations over different stages (Table 1).1 Because lesions are typically asymptomatic, syphilis is not always diagnosed early, and not all patients have typical signs at each stage of infection. Syphilis is most infectious in the primary and secondary stages, and congenital transmission is possible in the latent stage.8,10

| Stage | Duration | Manifestations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Uncommon | ||

| Primary | 10 to 90 days | Chancre | Local lymphadenopathy |

| Secondary | 1 to 3 months | Arthralgias, condylomata lata, fatigue, generalized lymphadenopathy, headache, hepatosplenomegaly, maculopapular/papulosquamous exanthema, myalgias, nephrotic syndrome, pharyngitis | Annular syphilis, iritis, pustular syphilis, pyrexia, syphilitic alopecia, ulceronodular syphilis |

| Early latent | After primary and secondary stages, up to 1 year of no symptoms | None | Secondary symptoms can recur |

| Late latent | More than 1 year of no symptoms | None | None |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Late neurosyphilis* | Cardiovascular or gummatous syphilis |

PRIMARY

Primary syphilis classically manifests as a solitary, nontender genital chancre or ulcer at the site of inoculation two to three weeks after exposure. Although chancres are most commonly seen in men on the distal penis, they can present on nearly any part of the body, including the vagina, cervix, and rectum. Multiple lesions are also possible11 (Figure 11). Without treatment, the primary lesions resolve in about three to six weeks without scarring; with treatment, they can resolve within days.6

SECONDARY

The secondary stage is the most commonly recognized clinical syndrome in syphilis. It occurs approximately six to eight weeks after the primary infection. This stage is associated with a painless maculopapular rash, often on the face or trunk and typically also involving the palms or soles (Figure 2).1 The secondary syphilis exanthem can be widespread or localized, pustular or scaly, and can involve mucous membranes or skin. Because of this variable presentation, the exanthem is commonly misdiagnosed as pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, a drug eruption, or another dermatologic condition. Lesions on mucous membranes can present as mucous patches (Figure 31) or verrucous lesions known as condylomata lata. Other signs and symptoms that can occur during the secondary stage include fatigue, headache, myalgias, sore throat, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and nephrotic syndrome. Without treatment, the manifestations of secondary syphilis gradually resolve within weeks to months.10,12

LATENT

Without diagnosis and treatment, syphilis eventually progresses to a latent stage characterized by a lack of symptoms. During the latent stage, the disease can be detected only through serologic testing. This stage is categorized into early and late latent syphilis to differentiate the risk of sexual transmission. The risk is highest in the first year of latency, when about 25% of people again manifest symptoms of secondary syphilis and become infectious to sex partners.1,10,12 After one year, they enter the late latency phase and remain asymptomatic.1,5

TERTIARY

Approximately one-third of patients with untreated latent syphilis eventually develop clinical manifestations of tertiary syphilis, which can occur years or even decades after the primary infection.1,12 During the tertiary stage, chronic low levels of infection can trigger a deleterious immune response, which causes the clinical constellations of cardiovascular syphilis, gummatous (late benign) syphilis, or late neurosyphilis. Cardiovascular syphilis targets large vessels and can present as ascending aortic aneurysm, aortic valve insufficiency, or coronary artery disease.13 Gummatous syphilis is characterized by a granulomatous process that can occur at virtually any location and causes symptoms through local inflammation or mass effect.8

NEUROSYPHILIS

Central nervous system involvement can occur at any stage of syphilis and manifests in a variety of ways. Ocular involvement causing uveitis or cranial nerve palsies can occur at any time in the disease course. People with secondary syphilis can present with aseptic meningitis. Meningovascular involvement can cause hemiplegia, aphasia, or seizures secondary to inflammation of the middle cerebral artery and its branches. Late in the disease course, chronic central nervous system infection can cause general paresis, a syndrome consisting of progressive dementia, seizures, and psychiatric symptoms. The other manifestation of late neurosyphilis, tabes dorsalis, is caused by involvement of the posterior columns and spinal nerve roots. This condition is associated with severe, unprovoked radicular pain, as well as ataxia caused by loss of proprioception.14,15

Congenital Syphilis

The incidence of congenital syphilis has been increasing since 2009.16,17 Most newborns with congenital syphilis (60% to 90%) are asymptomatic at birth.16,18 From birth to 48 months of age, syphilis is most commonly characterized by a morbilliform rash, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and signs of neurosyphilis (e.g., seizures, bulging fontanelle, cranial nerve abnormalities). When infants remain untreated beyond 48 months, they may develop late signs of the disease, most commonly tooth abnormalities, saddle nose deformity, and frontal bossing. Infants of mothers who test positive for syphilis during pregnancy should be evaluated for congenital syphilis through clinical examination and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing, with further testing as indicated.19

Screening

Screening for syphilis is recommended at least annually for high-risk groups. Sexually active people with HIV infection and men who have sex with men are at highest risk and should be screened more frequently. Evidence suggests that screening every three months detects more cases in these populations.20,21 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that when assessing a patient's risk of syphilis, clinicians should consider other factors associated with increased prevalence (Table 2).20,21 The optimal screening frequency is not well defined; clinicians should consider recent data and trends for specific populations and geographic areas when making individual screening decisions.20,21

| Current HIV infection |

| Geography: metropolitan areas, southern and western United States, areas of increasing prevalence according to public health data |

| History of incarceration |

| History of sex work |

| Males 29 years and younger |

| Men who have sex with men |

| Race and ethnicity (Blacks, Hispanics, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Hawaii Natives, and Pacific Islanders) |

Diagnosis

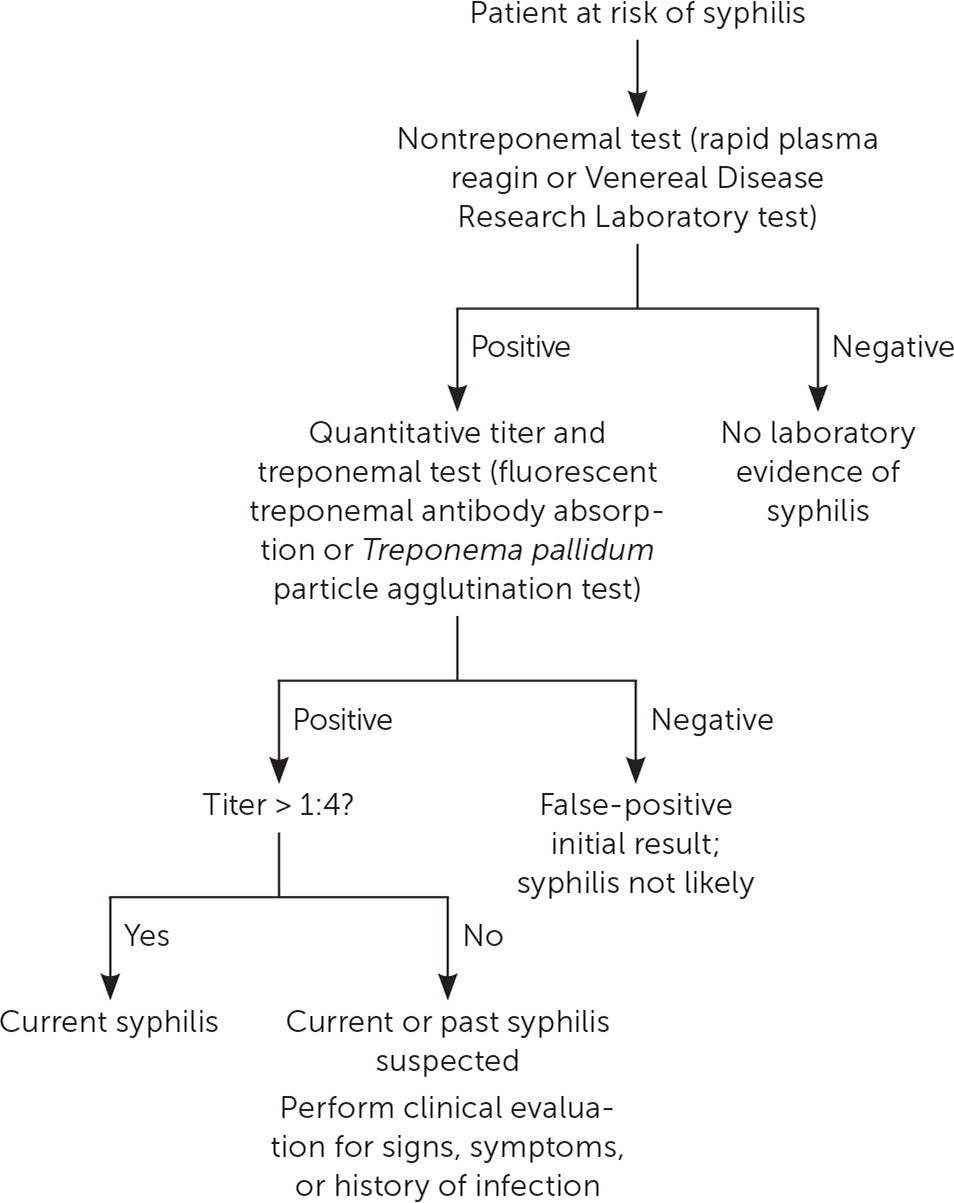

A detailed sexual history and physical examination, including genital and skin examinations, are key to the diagnosis of syphilis at all stages. The optimal choice of diagnostic testing for syphilis depends on the disease stage and symptoms, as well as the patient's history of previously treated syphilis. Current tests detect antibodies instead of directly identifying T. pallidum, and screening and diagnostic testing use a two-step approach with nontreponemal and treponemal-specific tests.

Nontreponemal tests (RPR or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL]) typically yield positive results within three weeks of primary chancre development. However, false-negative results are possible when serum antibody levels are extremely high, which can occur in primary or secondary syphilis. A positive nontreponemal test result should be quantified using a titer; these levels are used to monitor treatment response and to determine the presence of reinfection. False-positive RPR or VDRL results can occur in older or pregnant patients and in those with other infections or chronic inflammatory states.10,20,24,25

Treponemal-specific tests (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, T. pallidum particle agglutination, enzyme immunoassay, or chemical immunoassay) often yield positive results earlier than nontreponemal tests. Treponemal test results remain positive indefinitely and cannot be used to detect reinfection.10,20,24

Given the high rate of coinfection, all patients diagnosed with syphilis of any stage should also be tested for HIV infection.10

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The prevalence of syphilis in a population affects the diagnostic accuracy of the test sequencing approach (traditional vs. reverse sequence). The reverse-sequence approach (eFigure A) may detect cases that would be missed using the traditional approach (Figure 4); therefore, it may be preferred in high-prevalence populations. Because of the potential for false-positive results with the reverse-screening approach,20 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the traditional screening algorithm, particularly in low-prevalence populations.10 However, some studies suggest that the reverse-screening approach may have lower false-positive rates in low-prevalence populations because of improved specificity.26–28

DIAGNOSIS OF NEUROSYPHILIS AND OCULAR SYPHILIS

Patients with syphilis and neurologic or ocular symptoms should undergo a neurologic examination, ophthalmologic assessment, and lumbar puncture for VDRL testing of cerebrospinal fluid, which is the preferred diagnostic test for neurosyphilis.10,20,24,25 RPR testing of cerebrospinal fluid should not be performed.

DIAGNOSIS OF CONGENITAL SYPHILIS

Because maternal nontreponemal and treponemal immunoglobulin G antibodies pass through the placenta to the fetus, a positive serum test result in a newborn may reflect passive maternal antibodies. An RPR or VDRL titer that is four or more times higher than the maternal titer is suggestive of congenital syphilis.10,17 Congenital syphilis is associated with a high rate of stillbirth, and women with intrauterine fetal demise after 20 weeks' gestation should be tested for syphilis.10,20

Treatment

Penicillin is the mainstay of treatment for syphilis. Specific treatment regimens depend on the stage of disease (Table 3).10 A single dose of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units, is the preferred treatment for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis. The recommended regimen for late latent syphilis, latent syphilis of unknown duration, or tertiary nonneurologic syphilis consists of three weekly doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units each. The treatment of neurosyphilis requires intravenous aqueous crystalline penicillin G.10 Alternative antibiotics (doxycycline, azithromycin [Zithromax], and ceftriaxone [Rocephin]) have been studied in penicillin-allergic patients with primary or secondary syphilis. Although some studies showed that these medications are as effective as penicillin, further research is needed, and there is concern about macrolide resistance among T. pallidum.29–35 Patients may experience an acute febrile illness in the first 24 hours after treatment. This self-limited illness (Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction) is generally treated with supportive care, which may include antipyretics and increased fluid intake.36 Penicillin desensitization is recommended for pregnant women receiving treatment for syphilis.10

| Syphilis type | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Primary and secondary | Penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units IM 1 time In people allergic to penicillin: Doxycycline, 100 mg orally 2 times per day for 14 days (preferred) or Tetracycline, 500 mg orally 4 times per day for 14 days or Ceftriaxone (Rocephin), 1 to 2 g IM or IV per day for 10 to 14 days* or Azithromycin (Zithromax), single 2-g oral dose has been effective in some populations† |

| Early latent | Penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units IM 1 time |

| Late latent or latent of unknown duration | Penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units IM at 1-week intervals for 3 weeks |

| Tertiary | Penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units IM at 1-week intervals for 3 weeks |

| Ocular or neurosyphilis | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 18 to 24 million units IV per day, given as 3 to 4 million units every 4 hours or as continuous infusion, for 10 to 14 days Alternative if compliance is ensured: Penicillin G procaine, 2.4 million units IM 1 time per day for 10 to 14 days plus Probenecid, 500 mg orally 4 times per day for 10 to 14 days |

| Syphilis during pregnancy | Penicillin regimen appropriate for infection stage (desensitization may be required) |

| Congenital | Penicillin-based regimen that differs based on probability of infection (as determined by serology and cerebrospinal fluid testing)‡ |

Repeat serologic testing is recommended at six and 12 months after treatment to determine treatment effectiveness. A fourfold reduction in the nontreponemal titer is indicative of cure, and a reduction of less than fourfold may suggest treatment failure. As many as 20% of patients treated for primary or secondary syphilis do not achieve a fourfold titer reduction, and this necessitates additional follow-up and reevaluation for HIV infection. Syphilis cases should be reported to local public health agencies for disease surveillance and partner notification.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Mattei, et al.1 ; Brown and Frank37 ; and Birnbaum, et al.38

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms syphilis and/or diagnosis and treatment. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. We also searched the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statements, the Cochrane database, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: August 28, 2019, and March 7, 2020.