Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(3):173-180

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Acute pyelonephritis is a bacterial infection of the kidney and renal pelvis and should be suspected in patients with flank pain and laboratory evidence of urinary tract infection. Urine culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing should be performed in all patients and used to direct therapy. Imaging, blood cultures, and measurement of serum inflammatory markers should not be performed in uncomplicated cases. Outpatient management is appropriate in patients who have uncomplicated disease and can tolerate oral therapy. Extended emergency department or observation unit stays are an appropriate option for patients who initially warrant intravenous therapy. Fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole are effective oral antibiotics in most cases, but increasing resistance makes empiric use problematic. When local resistance to a chosen oral antibiotic likely exceeds 10%, one dose of a long-acting broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotic should also be given while awaiting susceptibility data. Patients admitted to the hospital should receive parenteral antibiotic therapy, and those with sepsis or risk of infection with a multidrug-resistant organism should receive antibiotics with activity against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms. Most patients respond to appropriate management within 48 to 72 hours, and those who do not should be evaluated with imaging and repeat cultures while alternative diagnoses are considered. In cases of concurrent urinary tract obstruction, referral for urgent decompression should be pursued. Pregnant patients with pyelonephritis are at significantly elevated risk of severe complications and should be admitted and treated initially with parenteral therapy.

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

Pyelonephritis

As of 2014, Escherichia coli resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones in the United States exceeded 35% and 10%, respectively.

A systematic review of 8 randomized controlled trials (N = 2,515) demonstrated equivalent clinical success rates in treating uncomplicated acute pyelonephritis with a 5- to 7-day course of fluoroquinolones compared with a 14-day course.

In the male subgroup of a 2017 randomized controlled trial, a 7-day course of ciprofloxacin was inferior to a 14-day course with respect to short-term cure rates with no differences in long-term outcomes.

Epidemiology and Microbiology

The highest incidence is among otherwise healthy women 15 to 29 years of age.3

Escherichia coli accounts for approximately 90% of uncomplicated pyelonephritis cases4,5; factors that define complicated pyelonephritis are listed in Table 1.6,7

Other causative organisms are more prevalent in complicated cases, but E. coli remains predominant4,5 (eTable A).

As of 2014, E. coli resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones in the United States exceeded 35% and 10%, respectively.5

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing uropathogenic organisms demonstrate resistance to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins and are increasingly prevalent in the United States and globally.5

Risk factors for infection with multidrug-resistant organisms are listed in Table 2.5,7

| Abnormal urinary tract anatomy or function; obstruction Chronic catheterization or recent urinary tract instrumentation Immunosuppression Increased risk of multidrug-resistant organisms (Table 2) Male sex* Older age, frailty Pregnancy Significant comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, organ transplant, sickle cell disease) |

| Uropathogen | Total (n = 521) | Uncomplicated (n = 286) | Complicated* (n = 235) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 86.9% | 95.1% | 77.0% |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4.8% | 1.4% | 8.9% |

| Enterococcus | 2.3% | 0% | 5.1% |

| Pseudomonas | 1.3% | 0% | 3.0% |

| Enterobacter | 1.0% | 0.3% | 1.7% |

| Proteus | 0.8% | 1.0% | 0.4% |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0.8% | 0% | 1.7% |

| Group B streptococcus | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0% |

| Other | 1.0% | 0.7% | 1.3% |

| Antimicrobial use within the past 3 months (particularly fluoroquinolones and antipseudomonal penicillins) |

| History of multidrug-resistant urinary isolate (e.g., extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms) |

| Hospitalization or institutionalization within the past 3 months |

| Indwelling urinary catheters |

| Travel outside the United States within the past 30 days |

| Urologic abnormalities |

Diagnosis

Flank pain and tenderness in the presence of pyuria are highly suggestive of pyelonephritis and differentiate it from other urinary tract infections.4,6,8,9

Fever is typically present but is not a universal symptom. Lower urinary tract symptoms (e.g., frequency, urgency, dysuria) may be absent in as many as 20% of patients.4,6,8,9

Other potential signs and symptoms of pyelonephritis include the following 4,6,8,9:

– Constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, chills, malaise)

– Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain

– Abdominal or suprapubic tenderness

– Tachycardia or hypotension

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Urine culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing should be performed in all patients; when clinically reasonable, urine culture should be performed before the patient receives antibiotics.7

Several studies demonstrate no reduction in contamination rates with preparatory cleansing or midstream catch; catheterization is not necessary for specimen collection.10–13

A basic metabolic profile and complete blood count help evaluate severity and can identify complications, particularly renal failure.9,14

Serum inflammatory markers have not been shown to assist in the diagnosis or treatment of pyelonephritis.14–18

Blood cultures should be considered only in diagnostically ambiguous situations, when patients fail to improve within 48 to 72 hours, or when urine culture is unlikely to grow a predominant organism (e.g., indwelling catheterization, patients already taking antibiotics). Blood cultures are positive in 10% to 40% of patients with acute pyelonephritis, but the presence of bacteremia rarely affects therapy.8,19–22

Initial imaging is not recommended in uncomplicated cases of acute pyelonephritis.23

Diagnostic imaging to identify obstruction or structural abnormalities should be considered in the following circumstances23,24:

– Sepsis

– Concern for urolithiasis

– New renal insufficiency with glomerular filtration rate less than or equal to 40 mL per minute per 1.73 m2

– Known urologic abnormalities

– Failure to respond to appropriate therapy within 48 to 72 hours

When diagnostic imaging is indicated, contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis is the preferred modality.23,25

When contrast or radiation is contraindicated, such as during pregnancy, ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging may be used.23

Treatment

INPATIENT VS. OUTPATIENT TREATMENT

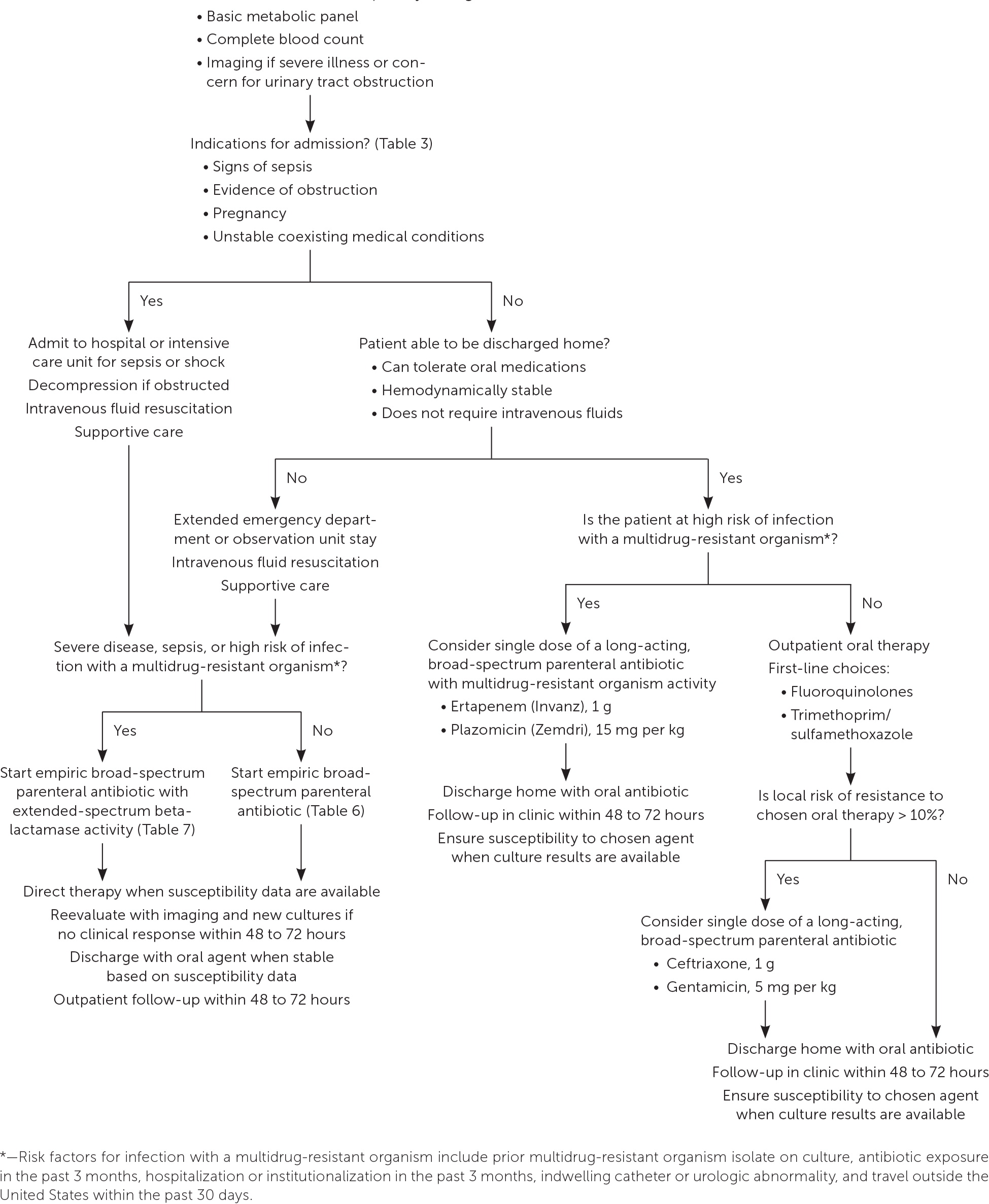

Outpatient management is appropriate in patients with uncomplicated pyelonephritis who are able to tolerate oral antibiotics and do not have clinical signs of sepsis. Indications for hospitalization are listed in Table 3.8,9

Evidence supports extended emergency department or observation unit stays as safe alternatives to immediate hospitalization for patients who warrant initial intravenous fluid resuscitation and/or are initially unable to tolerate oral agents but do not have complicating features or sepsis.7,9,26

A treatment algorithm is provided in Figure 1.

| Absolute indications Concurrent urinary tract obstruction Failure of outpatient therapy Oral antibiotic intolerance Pregnancy Sepsis Unstable coexisting medical conditions |

| Relative indications Frailty or poor social support High risk of infection with multidrug-resistant organism; hospital-acquired infection (Table 2) Severe, refractory pain Significant comorbidities or immunosuppression (e.g., diabetes mellitus, malignancy, organ transplant, sickle cell disease) Unreliable follow-up care |

SUPPORTIVE CARE

All patients should receive supportive care, as appropriate, with oral or intravenous fluid hydration, analgesics, antipyretics, and antiemetic medications.7

Patients presenting with signs of sepsis should receive intravenous crystalloid fluid resuscitation (30 mL per kg) within the first hour of presentation.27

ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY

Choice of antibiotic is informed by the clinical presentation, the patient's individual risk factors, and local resistance patterns. Therapy should be directed by urine culture susceptibility testing when available.7

Nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin (Monurol) do not attain adequate renal tissue concentration and should not be used to treat pyelonephritis.7

Options for oral antibiotic regimens for outpatients are listed in Table 4.7 Fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole have a significant evidence base that supports their use as safe and effective first-line oral therapies, with greater than 90% clinical success rates when the causative pathogens are susceptible.7

When local resistance to the chosen oral agent likely exceeds 10%, a single dose of a long-acting broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotic (e.g., ceftriaxone, ertapenem [Invanz], aminoglycosides) should also be given while awaiting susceptibility results7 (Table 57,28).

Oral beta-lactams are inferior to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and should not be used as first-line treatment of acute pyelonephritis.7

Hospitalized patients should initially receive parenteral antibiotic therapy; empiric options are listed in Table 6.7–9

Agents with activity against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms should be considered in patients with sepsis or risk factors for drug resistance (Table 7).7,9,27–29

| Agent and dosing | Length of treatment | Comments/pregnancy safety |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), 875 mg/125 mg twice daily* | 10 to 14 days | May use during pregnancy; has coverage for Enterococcus but not useful as empiric treatment for other organisms because of resistance patterns |

| Cefixime (Suprax), 400 mg once daily* | 10 to 14 days | May use during pregnancy, limited evidence for use |

| Cefpodoxime, 200 mg twice daily* | 10 to 14 days | May use during pregnancy, limited evidence for use |

| Cephalexin (Keflex), 500 mg twice daily* | 10 to 14 days | May use during pregnancy, increased resistance risk |

| Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily† | 7 days | No known risk of teratogenicity based on human and animal data |

| Ciprofloxacin extended release, 1,000 mg once daily† | 7 days | No known risk of teratogenicity based on human and animal data |

| Levofloxacin (Levaquin), 750 mg once daily† | 5 days | No known risk of teratogenicity based on human and animal data |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 160 mg/800 mg twice daily‡ | 14 days | Avoid use during pregnancy |

| Agent and dosing | Comments/pregnancy safety |

|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone, 1 g one time | May use during pregnancy |

| Ertapenem (Invanz), 1 g one time | May use during pregnancy; effective against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms |

| Gentamicin, 5 mg per kg one time | Avoid use during pregnancy*; can be nephrotoxic |

| Plazomicin (Zemdri), 15 mg per kg one time | Newer agent with activity against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms; limited evidence; cost and availability limit use; uncertain pregnancy safety |

| Agent and dosing | Comments/pregnancy safety |

|---|---|

| Cefepime, 1 to 2 g once daily | May use during pregnancy; consider dosage of 2 g every 8 hours when Pseudomonas aeruginosa is suspected |

| Ceftriaxone, 1 g once daily | May use during pregnancy |

| Ciprofloxacin, 400 mg every 12 hours | No known risk of teratogenicity based on human and animal data; good oral bioavailability; consider transition to oral dosing when tolerated |

| Gentamicin, 5 mg per kg once daily | Avoid use during pregnancy*; can be given as parenteral dose for 24 to 48 hours to augment oral regimen; can be nephrotoxic |

| Levofloxacin (Levaquin), 750 mg once daily | No known risk of teratogenicity based on human and animal data; good oral bioavailability; consider transition to oral dosing when tolerated |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), 3.375 to 4.5 g every 6 hours | May use during pregnancy; use 4.5-g dosage when P. aeruginosa is suspected |

| Agent and dosing | Comments/pregnancy safety |

|---|---|

| Ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz), 2.5 g every 8 hours | Newer agent with limited evidence; cost and availability limit usage; uncertain pregnancy safety |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa), 1.5 g every 8 hours | Newer agent with limited evidence; cost and availability limit usage; uncertain pregnancy safety |

| Ertapenem (Invanz), 1 g once daily | May use during pregnancy; useful dosing for outpatients; increased resistance among some extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms, use when susceptible |

| Imipenem/cilastatin (Primaxin), 500 mg every 6 hours | Uncertain pregnancy safety |

| Meropenem (Merrem IV), 1 g every 8 hours | Uncertain pregnancy safety |

| Meropenem/vaborbactam (Vabomere), 2 g/2 g every 8 hours | Newer agent with limited evidence; cost and availability limit usage; uncertain pregnancy safety |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), 3.375 to 4.5 g every 6 hours | May use during pregnancy; increased resistance among some extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing organisms, resistance can develop during treatment; use 4.5-g dosage when Pseudomonas aeruginosa is suspected |

| Plazomicin (Zemdri), 15 mg per kg once daily | Newer agent with limited evidence; cost and availability limit usage; uncertain pregnancy safety |

TREATMENT DURATION

A systematic review of eight randomized controlled trials (N = 2,515) demonstrated equivalent clinical success rates in treating uncomplicated acute pyelonephritis with a five- to seven-day course of fluoroquinolones compared with a 14-day course.30

There is limited evidence on the effectiveness of shorter courses (less than 14 days) of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. More studies are warranted before such treatment can be recommended.7,30

Acute pyelonephritis responds to appropriate therapy within 48 to 72 hours in more than 95% of cases.25

Patients not responding as expected (e.g., persistent fever, unimproved symptoms) should be further evaluated for alternative diagnoses, urinary tract obstruction, and/or antibiotic resistance with imaging, laboratory studies, blood cultures, and repeat urine culture.7–9,23

Special Considerations

UROLOGIC ABNORMALITIES AND/OR OBSTRUCTION

Urgent decompression is recommended in patients with acute pyelonephritis and urinary tract obstruction identified on imaging.8,9

Patients with structural urologic abnormalities or obstruction may benefit from longer antibiotic courses (10 to 14 days).23

To expedite clinical improvement, indwelling catheters that have been in place for two weeks or longer should be removed or replaced.31

PREGNANT PATIENTS

Pyelonephritis affects approximately 2% of all pregnancies, with 80% to 90% of cases occurring during the second and third trimesters.32,33

Pyelonephritis is associated with significant morbidity and mortality during pregnancy, with observed rates of septicemia and respiratory failure in 17% and 7% of patients, respectively.32,34

Because of the increased risk of serious complications, pregnant patients with pyelonephritis should be admitted to the hospital for initial parenteral antibiotic therapy and monitoring.33,35

Treatment options for pyelonephritis in pregnancy are limited because of a lack of evidence regarding antibiotic safety in utero. A Cochrane review of 10 trials (N = 1,125) found cefazolin or ceftriaxone to be effective.32

Pyelonephritis recurs in 6% to 8% of pregnant patients, and some experts have advocated for antibiotic suppression therapy with nitrofurantoin or cephalexin (Keflex) to reduce the risk of recurrence. However, data are insufficient to support this practice.36

MEN

Data are lacking on the appropriate treatment length and regimen for men with acute pyelonephritis.30

In the male subgroup of one randomized controlled trial, a seven-day course of ciprofloxacin was inferior to a 14-day course with respect to short-term cure rates, with no differences in long-term outcomes.37

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Colgan, et al.,8 and by Ramakrishnan and Scheid.6

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using Clinical Queries and medical subject headings with key terms pyelonephritis epidemiology; pyelonephritis microbiology; pyelonephritis risk factors; pyelonephritis diagnosis; pyelonephritis treatment; pyelonephritis length of treatment, hospitalization; and pyelonephritis, outpatient management of pyelonephritis. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, UpToDate, clinical guidelines and practice bulletins from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and evidence reports from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Search dates: July 3 and 27, 2019; August 6, 2019; and May 4, 2020.

The authors thank Anne Mounsey, MD, for mentorship, guidance, and review of the manuscript.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.