Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(1):72-80

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Acute diarrheal disease accounts for 179 million outpatient visits annually in the United States. Diarrhea can be categorized as inflammatory or noninflammatory, and both types have infectious and noninfectious causes. Infectious noninflammatory diarrhea is often viral in etiology and is the most common presentation; however, bacterial causes are also common and may be related to travel or foodborne illness. History for patients with acute diarrhea should include onset and frequency of symptoms, stool character, a focused review of systems including fever and other symptoms, and evaluation of exposures and risk factors. The physical examination should include evaluation for signs of dehydration, sepsis, or potential surgical processes. Most episodes of acute diarrhea in countries with adequate food and water sanitation are uncomplicated and self-limited, requiring only an initial evaluation and supportive treatment. Additional diagnostic evaluation and management may be warranted when diarrhea is bloody or mucoid or when risk factors are present, including immunocompromise or recent hospitalization. Unless an outbreak is suspected, molecular studies are preferred over traditional stool cultures. In all cases, management begins with replacing water, electrolytes, and nutrients. Oral rehydration is preferred; however, signs of severe dehydration or sepsis warrant intravenous rehydration. Antidiarrheal agents can be symptomatic therapy for acute watery diarrhea and can help decrease inappropriate antibiotic use. Empiric antibiotics are rarely warranted, except in sepsis and some cases of travelers’ or inflammatory diarrhea. Targeted antibiotic therapy may be appropriate following microbiologic stool assessment. Hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, and food and water safety measures are integral to preventing infectious diarrheal illnesses.

Acute diarrheal disease is a common cause of clinic visits and hospitalizations. In the United States, diarrhea accounts for an estimated 179 million outpatient visits, 500,000 hospitalizations, and more than 5,000 deaths annually, resulting in approximately one episode of acute diarrheal illness per person per year.1–5

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not order a comprehensive stool ova and parasite microscopic examination on patients presenting with diarrhea lasting less than seven days who have no immunodeficiency and no history of living in or traveling to endemic areas where gastrointestinal parasitic infections are prevalent. If symptoms of infectious diarrhea persist for seven days or more, start with molecular or antigen testing and next consider a full ova and parasite microscopic examination if other result is negative. | American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science |

Diarrhea is the passage of three or more loose or watery stools in 24 hours.5–7 Acute diarrhea is when symptoms typically last fewer than two weeks; however, some experts define acute as fewer than seven days, with seven to 14 days considered prolonged.2 Diarrhea lasting 14 to 30 days is considered persistent, and chronic diarrhea lasts longer than one month.2,5,7,8

Diarrhea can be categorized as inflammatory or noninflammatory. Inflammatory diarrhea, or dysentery, typically presents with blood or mucus and is often caused by invasive pathogens or processes. Noninflammatory or watery diarrhea is caused by increased water secretion into the intestinal lumen or decreased water reabsorption.2

Differential Diagnosis

| Noninflammatory diarrhea | Inflammatory diarrhea | |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Infectious: often viral, but may be bacterial and, less likely, parasitic Noninfectious: dietary, psychosocial stressors | Infectious: frequently invasive or toxin-producing bacteria Noninfectious: Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, radiation enteritis |

| History and examination | Infectious: nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort Noninfectious: nausea, abdominal discomfort, frequently without vomiting | Infectious: fever, abdominal pain, tenesmus, systemic signs and symptoms Noninfectious: abdominal pain, tenesmus, fatigue, weight loss |

| Laboratory findings | Infectious: often not performed; positive PCR or NAAT result Noninfectious: negative PCR or NAAT result, positive specific laboratory testing (e.g., antitissue transglutaminase antibody) | Infectious: positive PCR or NAAT result Noninfectious: negative PCR or NAAT result; positive for fecal calprotectin* |

| Common infectious pathogens | Bacterial: enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Clostridium perfrin-gens, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio cholerae Viral: Rotavirus, Norovirus Parasitic: Giardia, Cryptosporidium | Bacterial: Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli, entero-invasive E. coli, Clostridioides difficile, Yersinia Parasitic: Entamoeba histolytica |

Infectious inflammatory diarrhea is more severe and is typically caused by invasive or toxin-producing bacteria, although viral and parasitic causes exist.12 Bloody stools, high fever, significant abdominal pain, or duration longer than three days suggests inflammatory infection. The most identified inflammatory pathogens in North America are Salmonella, Campylobacter, Clostridioides difficile, Shigella, and Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.2,12

Specific pathogenic causes differ based on location, travel or food exposures; work or living circumstances (e.g., health care, long-term care settings); and comorbidities, such as HIV or other immunocompromised states.

Noninfectious causes of diarrhea include dietary intolerance, adverse medication effects, abdominal surgical processes such as appendicitis or mesenteric ischemia, thyroid or other endocrine abnormalities, and gastrointestinal diseases, such as Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis10,12 (Table 28,10,12). Although many of these processes are chronic, they can present acutely and should be included in the differential diagnosis of acute diarrhea.

| Potential causes | Examples |

|---|---|

| Abdominal processes | Appendicitis, ischemic colitis, malignancy |

| Dietary | Alcohol, caffeine, celiac disease (autoimmune), FODMAP malabsorption, lactose intolerance, nondigestible sugars |

| Endocrine abnormalities | Adrenal dysfunction, bile acid malabsorption, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, thyroid dysfunction |

| Functional | Irritable bowel syndrome, mental health comorbidities, overflow diarrhea due to fecal impaction |

| Inflammatory | Crohn disease, microscopic colitis, radiation enteritis, ulcerative colitis |

| Medication effects | Antibiotics, antineoplastic drugs, behavioral health medications (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors), hypoglycemic agents, magnesium-containing products |

Initial Evaluation

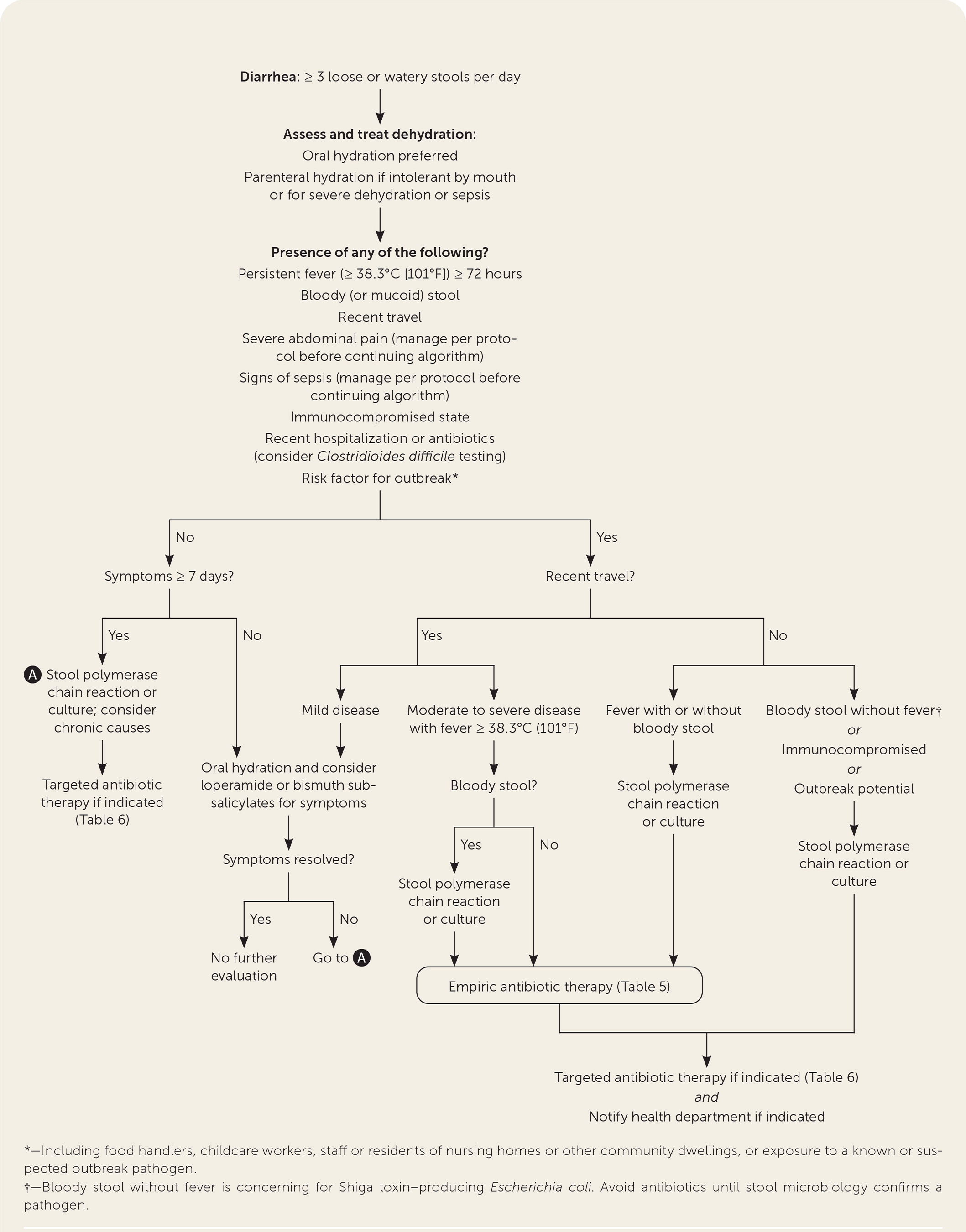

In countries with adequate food and water sanitation, most episodes of acute diarrhea are uncomplicated and self-limited, requiring only an initial evaluation and supportive treatment.2,6,12 The history and physical examination in patients with acute diarrhea should assess symptom severity, potential disease etiology, and personal risk factors for complications and should guide additional workup and treatment decisions.2 Figure 1 provides an approach to the evaluation and management of acute diarrhea.2,5

HISTORY

Additional exposure history can help suggest potential etiology and the need for further evaluation. Physicians should ask about recent travel, food or water exposures, known contacts with sick people, occupations, residence, recent medical history (e.g., illnesses, hospitalizations, antibiotics, other medications), and sexual history.2,9,12

| Finding | Significance | Further measures indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Associated signs and symptoms | ||

| Bloody stool Mucoid stool Persistent fever Severe abdominal pain | Inflammatory process | Stool studies (culture or multiplex polymerase chain reaction with reflex culture) Shiga toxin, if not included in polymerase chain reaction* |

| Confusion Decreased urine output Dizziness Syncope | Dehydration Possible sepsis | Restore volume status If septic, obtain blood cultures and stool studies |

| Symptoms lasting ≥ 7 days | Less reassuring for acute, self-limited process | Consider stool studies |

| Vomiting | Reassuring for likely viral etiology | None, unless otherwise indicated below |

| Personal risk factors | ||

| Age ≥ 65 years | Increased risk of severe disease | Keep higher concern for dehydration or invasive disease and evaluate as indicated |

| Childcare workers Community or nursing home workers or residents Food handlers | Increased risk of potential outbreak | Public health reporting as indicated Stool studies |

| History of pelvic radiation | Radiation enteritis | Consider specialty consultation |

| Immunocompromised | Increased risk of severe or invasive disease | Stool studies† |

| Known autoimmune disorders | Concern for flare-up or new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease | Additional measures based on suspicion for inflammatory bowel disease; consider specialty consultation |

| Recent hospitalization or antibiotic use | Concern for Clostridioides difficile | C. difficile testing per guidelines‡ |

| Recent travel | Increased concern for enteric fever or other location-specific pathogens | No additional measures unless indicated by symptoms above, persistent diarrhea, or associated with recent antibiotic use |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The initial physical examination should focus on disease severity and hydration status. Clinicians should take note of general appearance, fever, tachycardia, and hypotension. Peripheral pulses, skin turgor, and capillary refill may also assist in assessing volume status. The abdominal examination should evaluate for an acute abdomen requiring potential surgical intervention.2,12,13

Additional Evaluation

Further diagnostic evaluation is indicated for patients with inflammatory diarrhea or severe symptoms, including sepsis, or for those whose history includes risk factors for complications or potential outbreaks (e.g., patients who are immunocompromised, food handlers, health care or child-care workers, and community or nursing home residents).

STOOL TESTING

Most patients who are immunocompetent with acute, nonbloody diarrhea without systemic symptoms do not require stool testing.2,5,6,12,13 Stool studies should be obtained in patients with acute bloody diarrhea, fever, severe abdominal pain, signs of sepsis, or duration of seven days or greater, and patients with occupational or residential risk factors for an outbreak. Molecular, or culture-independent studies, also known as multiplex polymerase chain reaction or nucleic acid amplification tests, are generally preferred over traditional stool cultures.2,5,15 These methods allow for rapid detection of bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens concurrently. Multiplex testing in inflammatory diarrhea should include Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, C. difficile, and Shiga toxin. Specific exposures and travel history may dictate the need to test for additional pathogens. For example, patients who report swimming in brackish water or consuming undercooked shellfish warrant evaluation for Vibrio species.2

A limitation of molecular testing is that it identifies the presence of an organism but does not indicate clinical significance. Molecular methods are also of limited use in patients whose symptoms are related to an outbreak. If a clinician suspects an outbreak requiring a public health investigation, separate stool cultures are required to assist with reporting.2,5 Nationally reportable causes of death include specific pathogens (i.e., Campylobacter, giardiasis, Listeria monocytogenes, and others), foodborne outbreaks, waterborne outbreaks, and postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome.2

C. DIFFICILE

Adult patients who were recently hospitalized for more than three days or who used antibiotics within the past 12 weeks should undergo nucleic acid amplification testing or multistep testing for C. difficile. Testing requires a fresh, nonsolid sample. Evaluation and management guidelines for C. difficile can be found in separate updates.14,16

BLOOD TESTING

Blood testing is not routinely recommended for patients with acute diarrhea.12 A chemistry panel evaluating electrolytes and kidney function is appropriate for patients with dehydration. Complete blood count with differential and blood cultures should be obtained in patients with signs of sepsis. Patients with confirmed or suspected E. coli O157 or other Shiga toxin infections are at risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome. A blood cell count and chemistry panels should be obtained in these patients to monitor for changes in hemoglobin, platelets, electrolytes, and kidney function.2

NOT RECOMMENDED

Fecal leukocytes, lactoferrin, and calprotectin are of limited utility and are not recommended in the evaluation of acute infectious diarrhea.2,5,12 Fecal leukocytes break down easily in samples, reducing sensitivity. Fecal lactoferrin is more sensitive and can be associated with severe dehydration and bacterial etiology, but it lacks the specificity to be clinically useful.2,15,17 Fecal calprotectin, a marker of inflammatory bowel disease, has shown associations with bacterial causes for acute diarrhea, including C. difficile, but results lack consistency.2,17 Fecal occult blood testing generally should not be used in the evaluation of diarrhea.18

ENDOSCOPY

Patients with HIV, AIDS, and other immunocompromised conditions are at greater risk of invasive or opportunistic infections. An endoscopic examination should be considered in patients who are immunocompromised and whose initial stool testing is nondiagnostic or whose diarrhea is functionally disabling.2,20,21

Management

Treatment of acute diarrhea depends on the suspected or determined cause. Supportive therapy with early rehydration and refeeding is recommended regardless of etiology.

REHYDRATION AND REFEEDING

Oral rehydration solution has decreased the worldwide mortality of acute diarrhea, particularly in children and older people. Oral rehydration has been shown to decrease total stool output, episodes of emesis, and the need for intravenous rehydration, by slowly releasing glucose into the gut to improve salt and water reabsorption.22 Prepackaged oral rehydration solution is available commercially, but similar recipes can be made at home with readily available ingredients (Table 4).23

| Base beverage | Recipe |

|---|---|

| Chicken broth | 2 cups liquid broth (not low sodium) 2 cups water 2 tablespoons sugar |

| Gatorade | 32 oz Gatorade G2 3/4 teaspoon table salt |

| Water | 1 quart water 1/4 teaspoon table salt 2 tablespoons sugar |

ANTIDIARRHEAL MEDICATIONS

The antisecretory properties of bismuth subsalicylates and the antimotility properties of loperamide (Imodium) make these two drugs the most useful symptomatic therapies for acute watery diarrhea and can help decrease inappropriate antibiotic use. A loperamide and simethicone combination has demonstrated faster and more complete relief of acute watery diarrhea and gas-related abdominal discomfort compared with either medication alone.25

In cases of travelers’ diarrhea (TD), adjunct loperamide therapy with antibiotics has been shown to increase the likelihood of a clinical cure at 24 and 48 hours.26

ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

Most cases of acute watery diarrhea are self-limited; therefore, antibiotics are not routinely recommended. To avoid overuse of antibiotics and related complications, empiric antibiotics should be used in specific instances, including moderate to severe TD, bloody stool with fever, sepsis, and immunocompromised states.

A fluoroquinolone or macrolide is an appropriate first-line option when empirically treating TD, depending on local resistance patterns and recent travel history. Antibiotics can decrease the duration of TD to just over 24 hours after dosing.27,28 A single dose of antibiotics is usually sufficient, but three-day dosing is also an option (Table 5).5

| Organism | Indication for treatment | First choice | Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter | All identified cases | Azithromycin (Zithromax) | Ciprofloxacin |

| Clostridioides difficile | All identified cases | Fidaxomicin (Dificid)* | Oral vancomycin |

| Giardia | All identified cases | Tinidazole (Tindamax), nitazoxanide (Alinia) | Metronidazole (Flagyl) |

| Nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica | Consider in patients older than 50 years with immunosuppression or significant joint or cardiac disease | Ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, TMP/SMX, amoxicillin | Not applicable |

| Non- Vibrio cholerae | Invasive disease only, including bloody diarrhea or sepsis | Ceftriaxone plus doxycycline | TMP/SMX plus aminoglycoside |

| Salmonella enterica typhi or paratyphi | All identified cases | Ceftriaxone or ciprofloxacin | Ampicillin, TMP/SMX, azithromycin |

| Shigella spp. | All identified cases | Azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, or ceftriaxone | TMP/SMX, ampicillin if susceptible |

| Vibrio cholerae | All identified cases | Doxycycline | Ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, ceftriaxone |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | All identified cases | TMP/SMX | Cefotaxime (Claforan), ciprofloxacin |

STANDBY ANTIBIOTICS

Although previous guidelines recommended providing standby antibiotics to most travelers, studies have shown no significant illness reduction with self-treatment and have raised concerns about effects on the gut microbiota and antibiotic resistance. The decision to provide standby antibiotics should be individualized based on the patient’s risk of developing moderate to severe TD.5,29

PROBIOTICS

There are no formal recommendations for or against probiotics to treat acute diarrheal illness due to a lack of consistent evidence. One Cochrane review found that probiotics decrease the mean duration of acute diarrhea by one day and decrease the risk of diarrhea lasting more than four days. Another large meta-analysis found a 15% relative decrease in the risk of TD with prophylactic probiotic use.30,31 Other studies have shown inconclusive or insufficient evidence. The decision to use probiotics should be individualized for the patient and situation.30,31

Prevention

HYGIENE

Adequate handwashing, proper use of personal protective equipment, and food and water safety practices are mainstays for preventing the transmission of diarrheal illness. Proper handwashing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before rinsing shows the most benefit in reducing transmission of the more contagious pathogens (e.g., Norovirus, Shigella) and should be promoted in settings of community or institutional outbreaks. Patients who are hospitalized, including those with C. difficile colitis, may require contact precautions with appropriate personal protective equipment, including gloves and a gown.

Implementation of guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on food and water safety decreases the risk of foodborne diarrheal illness in the United States; however, the risk increases with travel. Pretravel counseling about high-risk food and beverages can be used to help prevent TD.5,9 A previous article in American Family Physician discussed foodborne illness in more detail.9

VACCINATION

Typhoid and cholera vaccines are recommended for people traveling to endemic areas or with known personal or occupational exposures.2 Vaccines for other diarrhea-causing agents continue to be investigated.

Sequelae

Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome is a common sequela of acute gastroenteritis, occurring in 4% to 36% of patients depending on the infective pathogen, with a pooled prevalence of 11% in one meta-analysis.32,33 Presenting as unexplained persistent diarrhea in the absence of an infectious agent, postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome is thought to be caused by an inability to downregulate intestinal inflammation following acute bacterial infection. Symptoms may last for months or years and are most common following Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella infection. Effective prevention and treatment of acute bacterial illness decrease the chances of developing postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome.32,33 Potential postinfectious diarrhea sequelae are listed in Table 7.2

| Erythema nodosum |

| Glomerulonephritis |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome |

| Hemolytic anemia |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| Immunoglobulin A nephropathy |

| Intestinal perforation |

| Lactose intolerance |

| Meningitis |

| Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome |

| Reactive arthritis |

COVID-19

Gastrointestinal adverse effects are common in patients with SARS-CoV-2. Symptoms vary among patients with COVID-19, and diarrhea may be the only presenting complaint for some. COVID-19–associated diarrhea is self-limited but may be severe in some patients. The overall clinical significance of COVID-19–associated diarrhea is unclear but causes concern about potential fecal-oral transmission of the virus.34

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Barr and Smith.12

Data Sources: A search was completed using PubMed, EBSCOhost, DynaMed, Essential Evidence Plus, and the Cochrane database. Key terms searched were acute diarrhea, travelers’ diarrhea, acute diarrhea evaluation, acute diarrhea testing, acute diarrhea treatment, diarrhea antibiotics, acute diarrhea prevention, postinfectious diarrhea, and COVID diarrhea. Also searched were the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization websites. Search dates: August 2021 to January 2022, and April 2022.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Army Medical Department, or the U.S. Army at large.