Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(1):36-43

Related Letter to the Editor: Commercial Oats and Patients With Celiac Disease

Patient information: See related handout on celiac disease, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Celiac disease is an immune-mediated, multisystem disorder that affects genetically susceptible individuals who are exposed to gluten-containing grains such as wheat, barley, and rye. The condition can develop at any age. Celiac disease presents with a variety of manifestations such as diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, bloating, malabsorption, and failure to thrive. Most adult patients will present with nonclassic symptoms, including less specific gastrointestinal symptoms or extraintestinal manifestations such as anemia, osteoporosis, transaminitis, and recurrent miscarriage. Immunoglobulin A tissue transglutaminase serologic testing is the recommended initial screening for all age groups. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy with small bowel biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis in most patients, including those with a negative serologic test for whom clinical suspicion of celiac disease persists. Biopsies may be avoided in children with high immunoglobulin A tissue transglutaminase (i.e., 10 times the upper limit of normal or more) and a positive test for immunoglobulin A endomysial antibodies in a second serum sample. Genetic testing for human leukocyte antigen alleles DQ2 or DQ8 may be performed in select cases. A gluten-free diet for life is the primary treatment, and patients may benefit from support groups and education on common and hidden sources of gluten, gluten-free substitutes, food labeling, balanced meal planning, dining out, dining during travel, and avoiding cross-contamination. Patients with celiac disease who do not respond to a gluten-free diet should have the accuracy of the diagnosis confirmed, have their diet reassessed, and be evaluated for coexisting conditions. Patients with refractory celiac disease should be treated by a gastroenterologist.

Celiac disease is an immune-mediated, multi-system disorder affecting genetically susceptible individuals exposed to gluten-containing grains (i.e., wheat, barley, and rye).1 The global prevalence is increasing, with the pooled prevalence of celiac disease identified at 0.7% for cases confirmed by biopsy and 1.4% for seroprevalence.2 The prevalence is higher in women than men (0.6% vs. 0.4%; P < .001), although this could be because of underdiagnosis in men.2–4 According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the prevalence of celiac disease in the United States varies between racial and ethnic groups, with a seroprevalence of 0.2% in non-Hispanic Black people, 0.3% in Hispanic people, and 1% in White people.4–6 Celiac disease may present with a variety of manifestations, can develop at any age, and is associated with a small increase in mortality risk.7–10 This article presents evidence-based answers to common questions about the evaluation and management of celiac disease.

What Are Risk Factors for Celiac Disease?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The presence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles DQ2 and DQ8 is the most important genetic risk factor for celiac disease. Although testing for HLA alleles DQ2 and DQ8 is not routinely used in the initial diagnosis, a negative test for both essentially rules out celiac disease with a negative predictive value of more than 99%.11,12 First-degree relatives of a person with celiac disease, and to a lesser extent second-degree relatives, are at increased risk.1,11 Monozygous twins have the highest risk, followed by siblings, parents, and children of patients with celiac disease.11 Other populations at risk of celiac disease are identified in Table 1.13

| Group | Percentage (%) affected |

|---|---|

| First-degree relatives of a person with celiac disease | 10 |

| Second-degree relatives of a person with celiac disease | 3 to 6 |

| People with the following conditions | |

| Down syndrome | 8 |

| Williams syndrome | 8 |

| Turner syndrome | 6 |

| Autoimmune thyroid disorders | 3 |

| Immunoglobulin A deficiency | 2 to 8 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 2 to 5 in adults |

| 3 to 8 in children | |

| General population | 1 |

Recent randomized multicenter trials of genetically at-risk infants demonstrated that breastfeeding and delaying gluten introduction did not change the risk of disease.14,15 However, a prospective cohort study showed that the amount of gluten consumed by genetically predisposed children during the first five years of life resulted in a statistically significant increased risk of celiac disease seropositivity (hazard ratio = 1.30; 95% CI, 1.22 to 1.30; P < .001) and celiac disease (hazard ratio = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.35 to 1.66; P < .001).16

How Do Patients With Celiac Disease Typically Present?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The clinical presentation of celiac disease is varied (Table 2).1,11,17,18 The classic symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, weight loss, malabsorption, and failure to thrive in patients at any age should prompt an evaluation for celiac disease.1,9,16 One of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms at presentation is diarrhea, particularly in adults. Other common gastrointestinal symptoms include bloating, aphthous stomatitis, alternating bowel habits, constipation, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.18

| Extraintestinal Amenorrhea Arthritis/arthralgia Chronic fatigue Chronic iron deficiency anemia Decreased bone mineralization (osteopenia/osteoporosis) Delayed puberty Dental enamel defects Depression Dermatitis herpetiformis–type rash | Elevated liver enzymes Epilepsy or ataxia Failure to thrive Peripheral neuropathy Recurrent miscarriage Repetitive fractures Stunted growth or short stature Unexplained infertility Unexplained weight loss | Intestinal Abdominal bloating and distension Alternating bowel habits Chronic abdominal pain Chronic constipation Chronic or intermittent diarrhea Gastroesophageal reflux disease Recurrent aphthous stomatitis Recurrent nausea and vomiting |

Most adult patients will present with nonclassic symptoms, including extraintestinal manifestations or less specific gastrointestinal symptoms.1,11,17,19 The most frequently identified extraintestinal manifestations include osteoporosis, anemia, transaminitis, and recurrent miscarriage.18 As many as 10% of children and 21% of adults with celiac disease will have subclinical illness.18,20 Delayed puberty and short stature are extraintestinal manifestations unique to childhood.17 Although celiac disease is associated with weight loss and failure to thrive, adults and children may be overweight or obese at the time of diagnosis.21,22

Who Should Be Tested for Celiac Disease?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Testing for celiac disease should be offered to all patients with classic symptoms.1,11,23 There is no consensus on which patients with nonclassic symptoms should be evaluated for celiac disease, but several professional organizations recommend consideration of screening for these patients.1,11,23 Active case finding, which is serologic testing for celiac disease among individuals with only subtle or atypical symptoms and in high-risk groups, is preferred by some organizations to increase the detection of patients with celiac disease.1,23

Although professional organizations vary in their recommendations, most support screening asymptomatic patients who have type 1 diabetes mellitus at diagnosis or first-degree relatives with celiac disease.1,11,23 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has concluded that there is insufficient evidence on the benefits, harms, or effectiveness of screening asymptomatic patients, including asymptomatic patients at increased risk.24

What Tests Are Indicated for a Patient Suspected of Having Celiac Disease?

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) tissue transglutaminase (tTG) serologic testing is the recommended initial screening test for celiac disease in all age groups. Some patients will need additional serologic testing, but most patients will require esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with small bowel biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.1,11,17,23,25

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

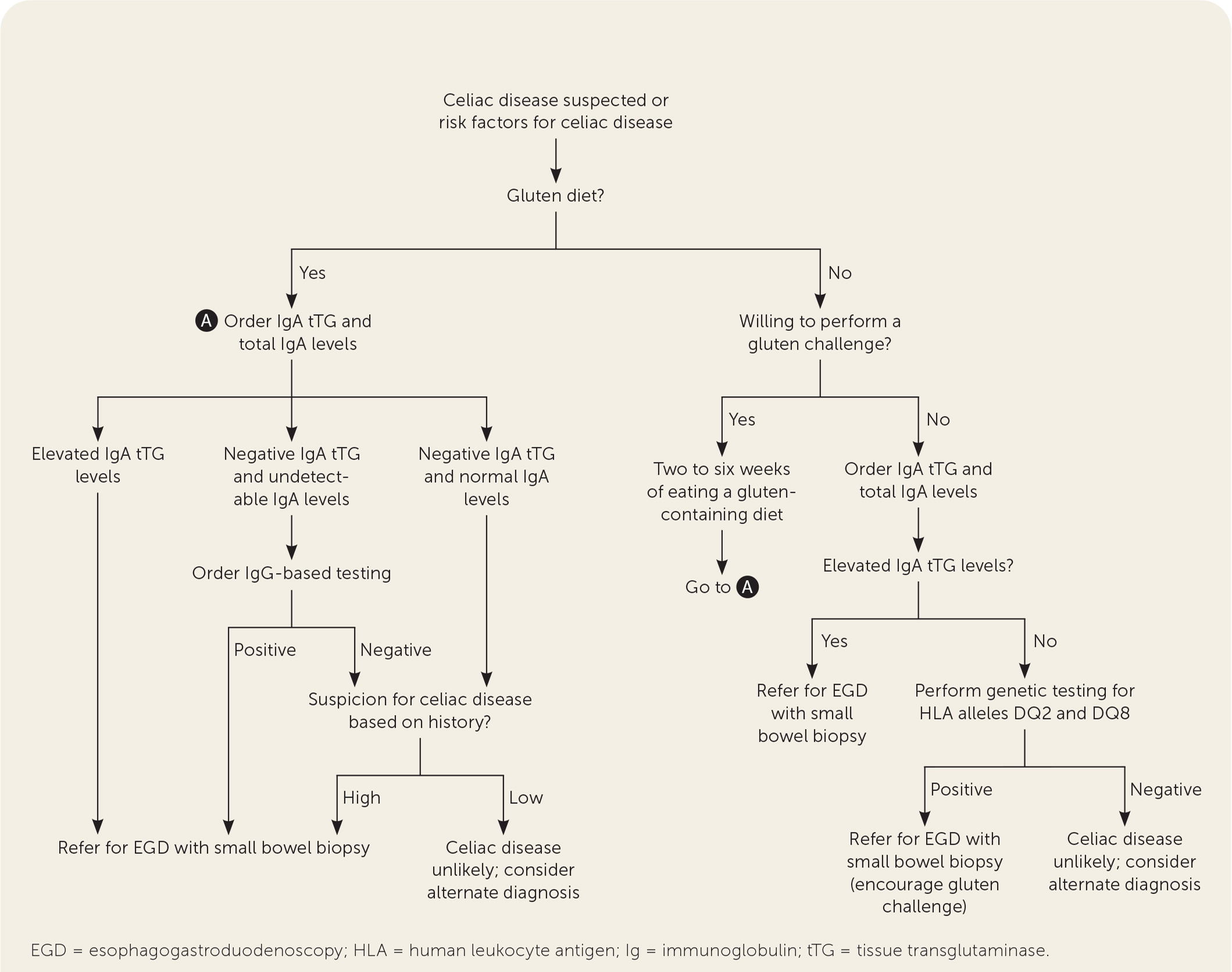

Serologic testing, EGD with small bowel biopsy, and the patient’s response to a gluten-free diet are used in combination to diagnose celiac disease (Figure 1).1,11,17,25 Initial testing should include antibody testing for IgA tTG because of its high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%).1,11 Total IgA levels should be measured in patients in whom celiac disease is strongly suspected because 2% to 3% of patients will have an IgA deficiency.11,23 In patients found to have low IgA levels or selective IgA deficiency, IgG testing (i.e., IgG deamidated gliadin peptides and IgG tTG) is the next step.1,11,17,23 The IgA endomysial antibody test is well suited for second-line confirmatory testing with a high specificity.17,25 No test has perfect sensitivity and specificity for celiac disease; therefore, some commercial panels may combine certain tests to increase diagnostic sensitivity. The use of combination testing beyond total IgA levels and IgA tTG is not recommended.11,17

EGD with small bowel biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of celiac disease, including in patients with negative serologic testing for whom clinical suspicion of disease remains.1,11,23 The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition’s 2012 guideline, updated in 2020, recommends that a no-biopsy approach is safe in children with high IgA tTG (i.e., 10 times the upper limit of normal or more) and a positive test for IgA endomysial antibodies in a second serum sample.17 Although a recent prospective cohort study demonstrated that similarly high IgA tTG levels in adults had a strong predictive value for intestinal biopsy changes diagnostic of celiac disease, supporting the potential use of a no-biopsy approach,26 current guidelines still recommend EGD with small bowel biopsy for diagnosis in adults.1,11,23

All serologic testing should be completed after the patient has been on a gluten-containing diet of 3 g of gluten per day for two to six weeks, depending on tolerability, to prevent false-negative results.1,11,17 If a patient is unwilling to attempt a gluten trial, or if there are inconclusive celiac antibodies or intestinal biopsy findings, genetic testing for HLA alleles DQ2 and DQ8 may be performed.1,11,17,23,25 A negative test makes the diagnosis of celiac disease highly unlikely.1,11,17

How Is Celiac Disease Treated?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The primary treatment of celiac disease is a lifelong gluten-free diet1,11,23,27–30 (Table 331,32). Within six to 12 months, patients who respond to being on a gluten-restricted diet will experience symptom relief and immunologic improvement on repeat laboratory testing.11,25 Several nutrients that are often deficient secondary to malabsorption will start to recover.1,11 Adherence to a gluten-free diet improves quality of life in individuals with symptomatic celiac disease.27–29,31

| Grains that should be avoided |

| Barley (includes malt), rye, wheat (includes kamut, semolina, spelt, triticale) |

| Safe grains (gluten free) |

| Amaranth, buckwheat, corn, millet, oats, quinoa, rice, sorghum, teff |

| Sources of gluten-free starches that can be used as flour alternatives |

| Cereal grains: amaranth, buckwheat, corn, millet, Montina, quinoa, sorghum, teff |

| Legumes: chickpeas, kidney beans, lentils, navy beans, pea beans, peanuts, soybeans |

| Nuts: almonds, cashews, chestnuts, hazelnuts, walnuts |

| Seeds: flax, pumpkin, sunflower |

| Tubers: arrowroot, jicama, potato, tapioca, taro |

Adherence to a gluten-free diet is challenging, particularly because of the strict limitation placed on gluten intake, with the recommendation to consume less than 10 mg per day.33,34 One slice of wheat bread contains approximately 2 g of gluten.35 Patients may benefit from consultation with a registered dietitian who has experience managing celiac disease.1,11,23 Online resources and support groups may be recommended. Dietary education should cover common and hidden sources of gluten, gluten-free substitutes, food labeling, balanced meal planning, dining out, dining during travel, and avoiding cross-contamination.23

Some nutritional deficiencies improve with dietary management of celiac disease; however, a gluten-free diet is often limited by low protein and fiber content, as well as high fat and salt content.36 Inadvertent gluten exposure and refractory celiac disease cause persistent micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies (e.g., iron, calcium, selenium, zinc, magnesium, vitamin B12, folate, vitamin C, vitamin D).37 Because of difficulties with dietary adherence and persistent symptoms for some patients, therapeutic approaches including endopeptidases, gluten-sequestering polymers, probiotics, tight junction modulators, HLA alleles DQ2 and DQ8 blockers, and transglutaminase inhibitors are being studied in clinical trials.38,39

What Are Barriers to Gluten-Free Diet Adherence?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Initiating and maintaining a gluten-free diet requires significant shifts in dietary habits. Rates of gluten-free diet adherence in adults and children with celiac disease range from 23% to 98%.40 Adolescents are particularly at risk for nonadherence.40 Gluten nutritional literacy, balanced meal planning, and dining out are known factors that influence adherence. Family meals, purchasing food or dining out during travel, and eating in social settings can be particularly challenging.41 Cross-contamination can lead to inadvertent nonadherence.44 The supply of gluten-free ready-made foods is increasing, but these foods are on average 183% to 242% more expensive than similar wheat-based products.42,43 There is variability in the cost of gluten-free products based on where they are sold, with traditional grocery stores being the least expensive option. Health food stores and upscale markets offer the greatest availability.43 Limited availability of gluten-free foods, cost, and unclear labeling impact dietary adherence, but patient knowledge regarding celiac disease and a gluten-free diet improves adherence.36,45

How Should Patients Be Monitored Following Diagnosis of Celiac Disease?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients with celiac disease require long-term follow-up to monitor for persistent or new symptoms and gluten-free diet adherence and to assess for complications, including nutrient deficiencies and concomitant autoimmune disorders. Close interval follow-up in the initial 12 months after diagnosis should be considered to aid in dietary compliance and symptom monitoring and then annually or biannually thereafter.1,11,23,25 At diagnosis, and annually if abnormalities were detected during the initial laboratory investigation, a complete blood count, thyroid function testing, and iron panel should be performed, and calcium, phosphate, vitamin D, folate, vitamin B12, and liver enzyme levels should be evaluated.1 Based on dietary history and symptoms, physicians may consider testing for additional micronutrient deficiencies such as zinc and copper.1,11,36 In children and adolescents, height and weight should be monitored to ensure normal growth and development.1,23,25 Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities; patients should be monitored routinely and treated appropriately.46,47

Symptom monitoring and serologic testing are critical to evaluate for adherence to a gluten-free diet. Repeat serologic testing may be performed in the first three to six months after diagnosis, then annually.1,11 A decrease in baseline values is expected within months of strict gluten-free diet adherence. Serologic monitoring appears most beneficial for its positive predictive value in detecting those with gluten in their diet.48 A repeat EGD with small bowel biopsy should be considered for patients with good adherence to a gluten-free diet who have persistently elevated titers or continued symptoms.1,9,11,23

What Steps Should Be Taken When a Patient Is Nonresponsive or Refractory to Treatment?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients with nonresponsive celiac disease have persistent or recurrent malabsorptive symptoms, positive serologic testing, or villous atrophy on EGD despite six to 12 months of gluten-free diet adherence.1,8,11 Between 7% and 30% of adult patients treated with a gluten-free diet will experience persistent symptoms.1,11 The accuracy of the diagnosis for patients experiencing persistent symptoms should be carefully reconsidered, including a review of serology and pathology. Although continued gluten ingestion is the most common cause of nonresponsive celiac disease in 35% to 50% of patients, other coexisting conditions such as lactose intolerance, bacterial overgrowth, irritable bowel syndrome, and microscopic colitis should be considered.1,11 A dietitian who specializes in celiac disease may assist in identifying potential sources of gluten ingestion.1,11,23

Patients who have persistent or recurrent symptoms with associated histologic changes (e.g., villous atrophy) on small bowel biopsy despite six to 12 months of gluten-free diet adherence and in the absence of other disorders have refractory celiac disease. These patients require intense medical management and should be treated by a gastroenterologist.1,11,23

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Nelsen49; Presutti, et al.50; and Pelkowski and Viera.13

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term celiac disease, with additional search terms of incidence, prevalence, diagnosis, therapy, prognosis, and gluten-free diet. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Cochrane database, AHRQ.gov, and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statements were also searched. Reference lists from key articles were reviewed by additional resources. Essential Evidence Plus was searched using the key terms celiac disease and gluten. Search dates: February 2021; April 2021; August 2021; and April 8, 2022.

The contents of this article are solely the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. military at large, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.