Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):165-172

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm is a pathologic condition with progressive abdominal aortic dilatation of 3.0 cm or more that predisposes the abdominal aorta to rupture. Most abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic until they rupture, although some are detected when an imaging study is performed for other reasons. The risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm include hypertension, coronary artery disease, tobacco use, male sex, a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm, age older than 65 years, and peripheral artery disease. Abdominal ultrasonography is the preferred modality to screen for abdominal aortic aneurysm because of its cost-effectiveness and lack of exposure to ionizing radiation. Abdominal aortic aneurysm can be managed medically or surgically, depending on the patient's symptoms and the size and growth rate of the aneurysm. Medical management is appropriate for asymptomatic patients and smaller aneurysms and includes tobacco cessation and therapy for cardiovascular risk reduction. Surgical management, which includes open and endovascular aneurysm repair, is indicated when the aneurysm diameter is 5.5 cm or larger in men and 5.0 cm or larger in women. Surveillance of abdominal aortic aneurysm depends on the size and growth rate of the aneurysm. The most serious complication of abdominal aortic aneurysm is rupture, which requires emergent surgical intervention. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that men with a history of smoking who are 65 to 75 years of age should undergo one-time abdominal aortic aneurysm screening with ultrasonography.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is the abnormal dilatation of the infrarenal abdominal aorta of 3.0 cm or more.1 It occurs when the abdominal aortic wall weakens, causing it to bulge or balloon, resulting in permanent and progressive focal dilatation of the abdominal aorta2 (Figure 1). AAA is the 14th leading cause of mortality in the United States, resulting in 4,500 deaths each year.3 Approximately 45,000 surgeries for AAA repair are performed annually.1,3 AAA affects about 1.5% of men older than 60 years and 1% of women older than 64 years.4 Women are known to have worse outcomes with AAA than men. This is likely due to the lack of screening and late presentation associated with larger aneurysms that tend to grow faster and have a four times higher risk of rupture at diameters of 5.0 cm to 5.9 cm.5 The average annual risk of rupture for aneurysms that are 6.0 cm or larger is more than 10%.6 A ruptured AAA is associated with high mortality rates. Between 59% and 83% of patients die before they reach a hospital or have surgery.1

A history of smoking is responsible for 75% of AAAs.7 In 2005, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended one-time ultrasonography to screen for AAA in men 65 to 75 years of age who had ever smoked. This recommendation was updated in 2014 and 2019 and is supported by the American Academy of Family Physicians. Epidemiologic literature defines a patient with a history of smoking as someone who has smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime.8 Although the recommendations are stratified by men and women, the net benefit is driven by biological sex rather than gender identity.

Pathophysiology

AAA occurs from the degenerative process of smooth muscle cell loss and structural deterioration of the aortic wall, specifically within the elastic media and adventitia.9 Matrix metalloproteinase, a proteolytic enzyme released by T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, and other chronic inflammatory cells, destroys the elasticity and collagen of smooth muscle.10,11

Risk Factors

Cigarette smoking is the greatest risk factor for developing AAA. Other risk factors include a family history of AAA and conditions that are associated with cardiovascular disease such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and stroke (Table 1).6,12 Although diabetes mellitus alone is not a risk factor for AAA, when associated with coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease, it is linked to AAA growth and rupture.13

| Major risk factors |

| Male sex* |

| Older than 65 years* |

| Tobacco use* |

| Additional risk factors |

| Atherosclerosis |

| Cerebrovascular disease |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Family history (i.e., first-degree relatives) of abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| History of aneurysm on a peripheral vessel |

| Hypertension |

| Obesity |

| Peripheral artery disease |

Presentation

Most AAAs are asymptomatic until they rupture, although some may be identified during an evaluation of abdominal symptoms. AAA is often detected as an incidental finding when ultrasonography, computed tomography of the abdomen, or magnetic resonance imaging is performed for other purposes. For patients who present with unexplained abdominal discomfort, such as pain that radiates to the back, flank, and groin, abdominal palpation is reasonably accurate in diagnosing AAA and does not increase the risk of rupture.12 One study reported that the sensitivity of abdominal palpation increases significantly with AAA diameter, ranging from 29% for aneurysms 3.0 cm to 3.9 cm, 50% for those 4.0 cm to 4.9 cm, and 75% for those 5.0 cm or larger.14 The most common finding on the abdominal examination is a pulsatile mass around the umbilicus. A bruit can sometimes be heard on the pulsatile mass. Patients with popliteal artery aneurysms have a high prevalence of AAA and vice versa.15 Therefore, examining both popliteal arteries and the abdominal aorta is important when an arterial aneurysm is suspected. One study found that abdominal obesity can decrease the sensitivity of palpation.14 Physical examination has been used in practice but has low sensitivity (39% to 68%) and specificity (75%) and is not recommended for screening in patients who are obese.

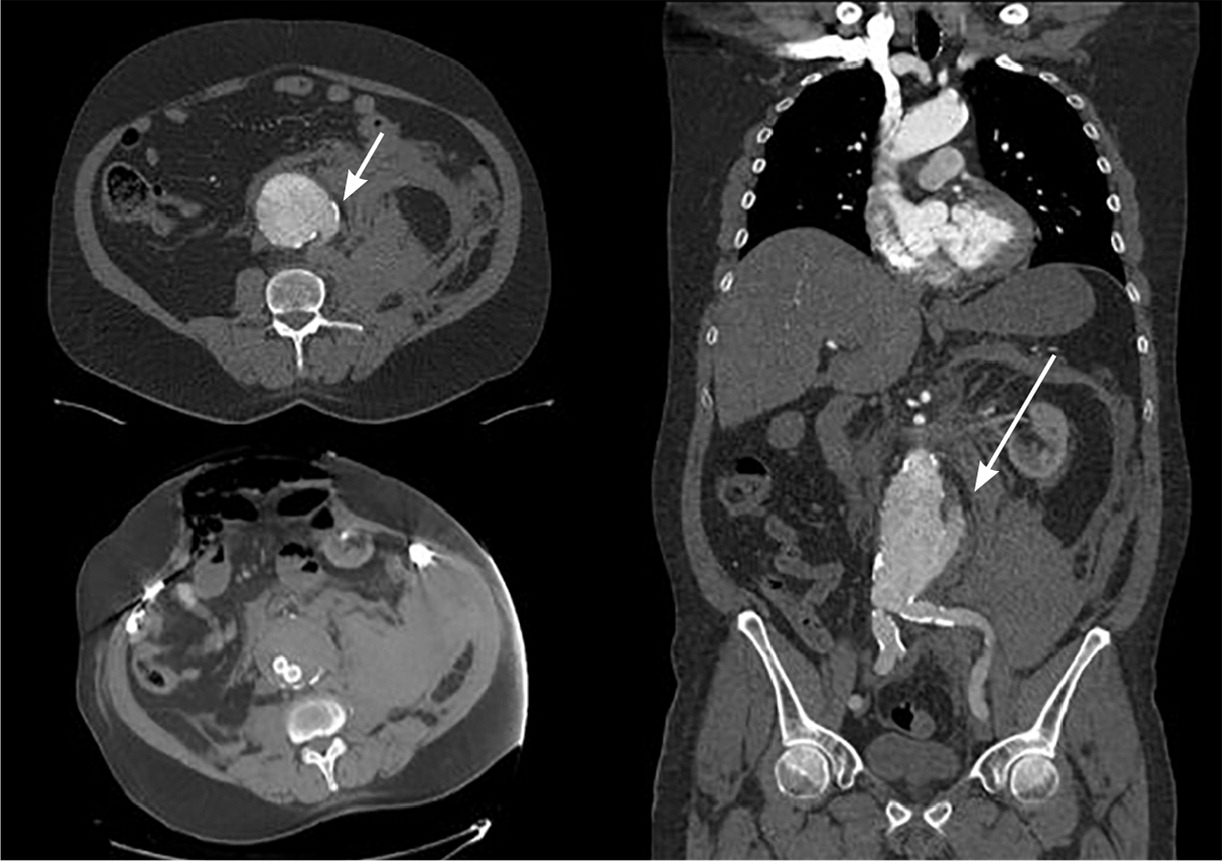

Patients with a ruptured aneurysm typically present with sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, back pain, severe hypotension, lower extremity weakness, loss of pulses on bilateral lower extremities, and a pulsatile abdominal mass. Ruptured aneurysms can also present with Grey Turner sign, which is ecchymosis or discoloration on the flanks, and Cullen sign, which is periumbilical ecchymosis.16 A ruptured aneurysm is a medical and surgical emergency. Misdiagnosis in the setting of rupture is common.17 About 50% of patients with a ruptured AAA reach the hospital alive; of those, up to 50% do not survive surgical repair.18 Figure 2 shows a computed tomography scan of a ruptured AAA.

Screening

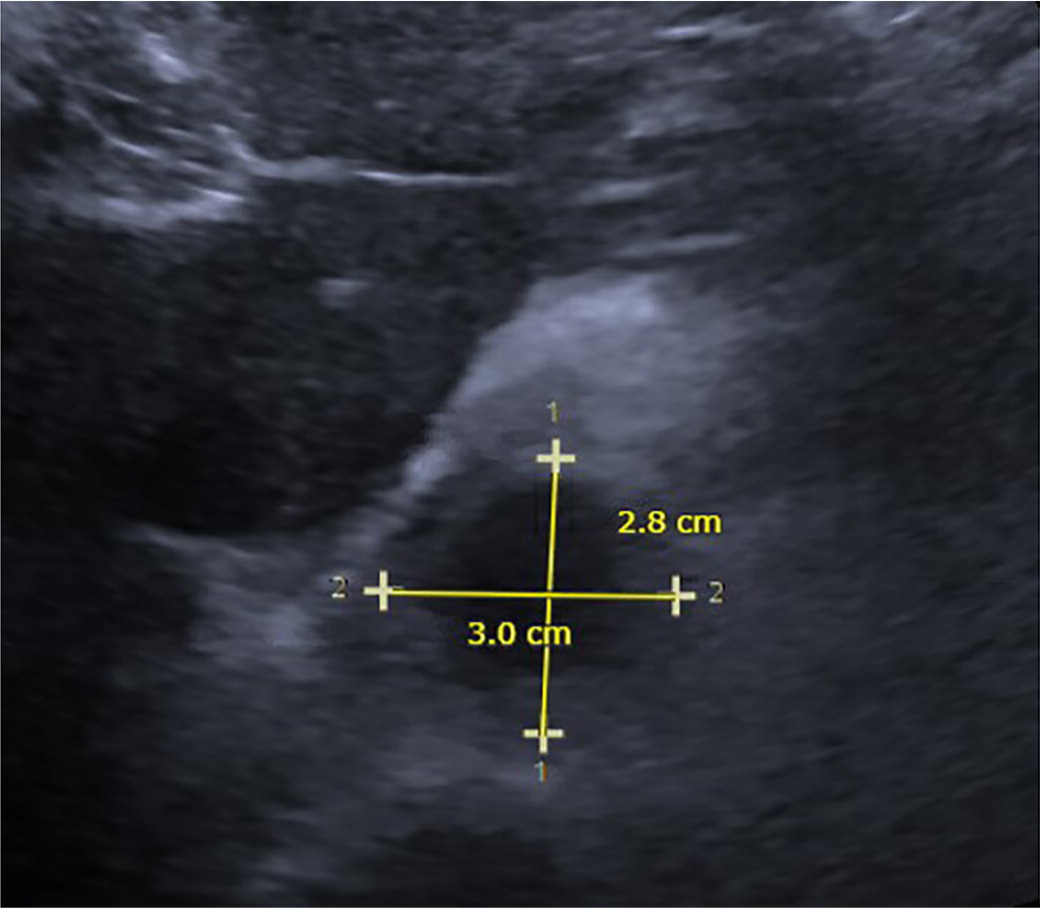

Ultrasonography has been widely used to screen for AAA (Figure 3). Based on the current USPSTF guideline, men 65 to 75 years of age who have ever smoked should have onetime screening for AAA with ultrasonography.8 The USPSTF also recommends selectively offering screening ultrasonography to men 65 to 75 years of age who have never smoked, but who have risk factors for AAA.8 The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for AAA in women who have never smoked and have no family history of the condition.8 The current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AAA in women 65 to 75 years of age who have ever smoked or have a family history of AAA.8

Ultrasonography is the preferred modality to screen for AAA and is cost-effective, nonradiating, and noninvasive. It is highly sensitive (94% to 100%) and specific (98% to 100%) for detecting AAA.19,20 However, ultrasound image quality can be attenuated by the presence of adipose tissue in people weighing more than 113.40 kg to 136.08 kg (250 lb to 300 lb).21 A small prospective observational study found that AAA screening can be safely performed by family physicians who are trained to use point-of-care ultrasound technology.22 Screening for AAA by family physicians might greatly benefit rural populations and people who have other barriers to medical care, such as lack of transportation.

Surveillance

Although definitive recommendations and evidence for AAA surveillance are lacking, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the Society for Vascular Surgery provide guidance based on the size of the aneurysm.12,23 The risk of growth increases with aneurysm size. Aneurysms with a diameter of 2.8 cm to 3.9 cm can expand 1.9 mm per year; those 4.0 cm to 4.5 cm can expand 2.7 mm per year; and those 4.6 cm to 8.5 cm can expand 3.5 mm per year (Table 2).24 The size of the diameter is crucial in determining the risk of rupture. Aneurysms 5.0 cm to 6.0 cm in diameter have a 3% to 15% risk of rupture within one year; those 6.0 cm to 7.0 cm have a 10% to 20% risk, those 7.0 cm to 8.0 cm have a 20% to 40% risk, and aneurysms larger than 8.0 cm have a 30% to 50% risk of rupture within one year (Table 3).25 Therefore, it is reasonable to repeat ultrasonography for aneurysms with a diameter of 3.0 cm to 3.9 cm every two to three years, and every six to 12 months for aneurysms 4.0 cm to 4.9 cm (Table 412,23,26). Based on the Society of Vascular Surgery recommendations, consider referral to a vascular surgeon at the time of initial diagnosis.12

| Diameter (cm) | Expansion rate (mm per year) |

|---|---|

| 2.8 to 3.9 | 1.9 |

| 4.0 to 4.5 | 2.7 |

| 4.6 to 8.5 | 3.5 |

| Aneurysm size (cm) | Risk of rupture within one year (%) |

|---|---|

| < 4.0 | 0 |

| 4.0 to 5.0 | 0.5 to 5 |

| 5.0 to 6.0 | 3 to 15 |

| 6.0 to 7.0 | 10 to 20 |

| 7.0 to 8.0 | 20 to 40 |

| > 8.0 | 30 to 50 |

| Aneurysm diameter | ACC/AHA recommendation | SVS recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Larger than 2.5 cm but smaller than 3.0 cm | No surveillance | Rescreen after 10 years but consider referral to a vascular surgeon after initial diagnosis |

| 3.0 cm to 3.9 cm | Every two to three years | Every three years |

| 4.0 cm to 5.4 cm | Ultrasonography or computed tomography every six to 12 months Consider vascular surgery referral if diameter of aneurysm is 5.0 cm or larger Elective repair is recommended for appropriate surgical candidates with aneurysms 5.0 cm or larger | Every 12 months for aneurysms 4.0 cm to 4.9 cm Every six months for aneurysms 5.0 cm to 5.4 cm Women who have an aneurysm diameter of 5.0 cm to 5.4 cm may be considered for elective surgery |

| Larger than 5.4 cm | Surgical repair | Men who have an aneurysm of 5.5 cm or larger and low surgical risk may be considered for elective surgery |

Medical Management

AAA can be managed medically or surgically, depending on the patient's symptoms and the size and growth rate of the aneurysm. The goal of medical management is to prevent AAA rupture and avoid invasive treatment by preventing aneurysm enlargement or reducing aneurysm size. Medical management is appropriate for asymptomatic patients and smaller aneurysms. Studies suggest that smoking has been associated with AAA, and self-reported current smokers have a faster growth rate than former smokers, approximately 0.4 mm per year.24 Therefore, smoking cessation should always be encouraged in patients with known AAA.24,27

There are no recommendations for direct interventions to reduce AAA expansion and the need for repair. Administering beta blockers, such as propranolol, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, doxycycline, and roxithromycin (not available in the United States) for the purpose of reducing the risk of AAA expansion and rupture is not recommended.12 Early studies with a small sample size and limited follow-up suggested that the anti-inflammatory effects of certain antibiotics may reduce the AAA expansion rate.28–30 One recent study of doxycycline, which was previously found to lower matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels, did not reduce aneurysm growth over two years.29 Medical management of AAA predominantly involves cardiovascular risk reduction such as antihypertensive, statin, and antiplatelet therapy.28,31–33 Antihypertensive therapy should target the patient's blood pressure goal. A meta-analysis showed that statins are associated with attenuation of AAA growth by slowing the progression of atherosclerotic disease.34 Patients with AAA are at high risk of cardiovascular events, and most guidelines recommend the use of anti-platelet agents for secondary prevention, such as aspirin (81 mg) or clopidogrel (Plavix) for those intolerant of aspirin.28,31 A combination of statins and beta blockers is associated with a reduction of perioperative mortality and incidence of non-fatal myocardial infarction for patients undergoing surgery for AAA.32 Competitive sports and intense isometric exercises are usually discouraged in people who have AAA.33

Surgical Management

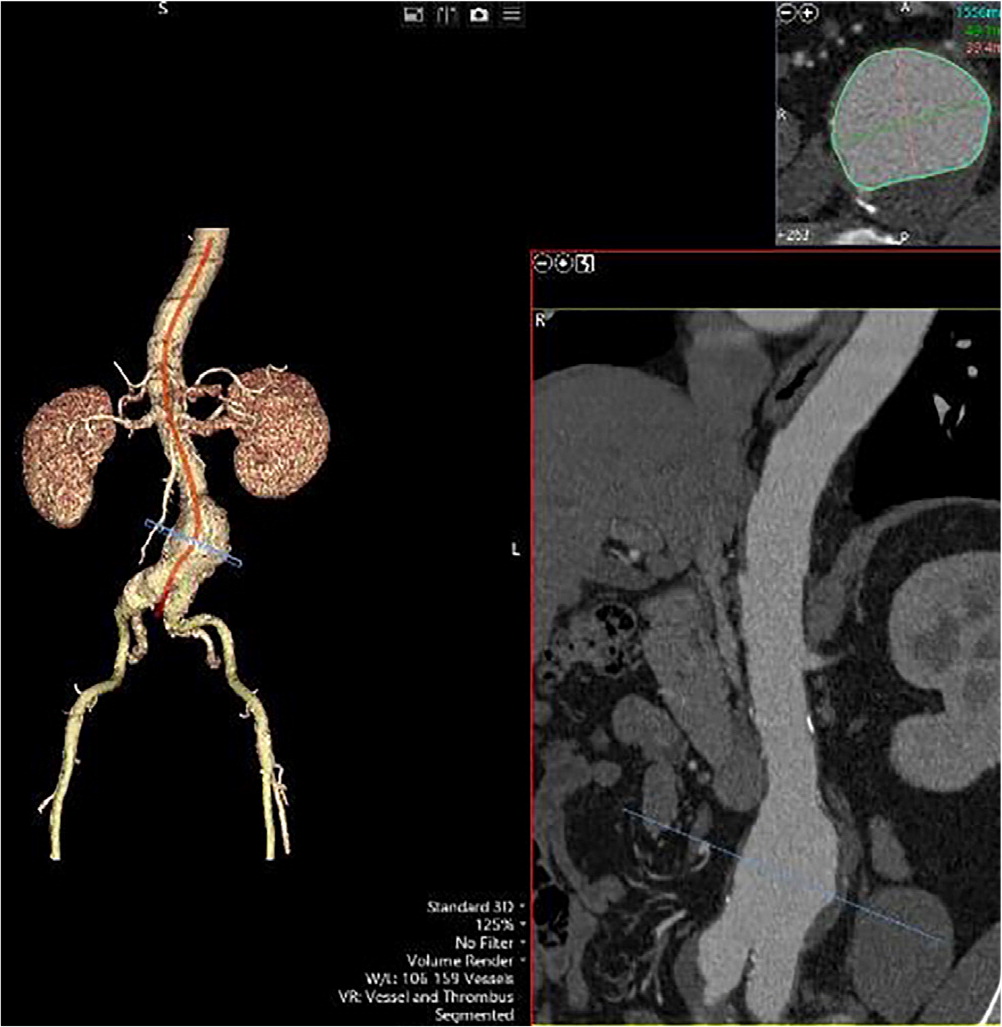

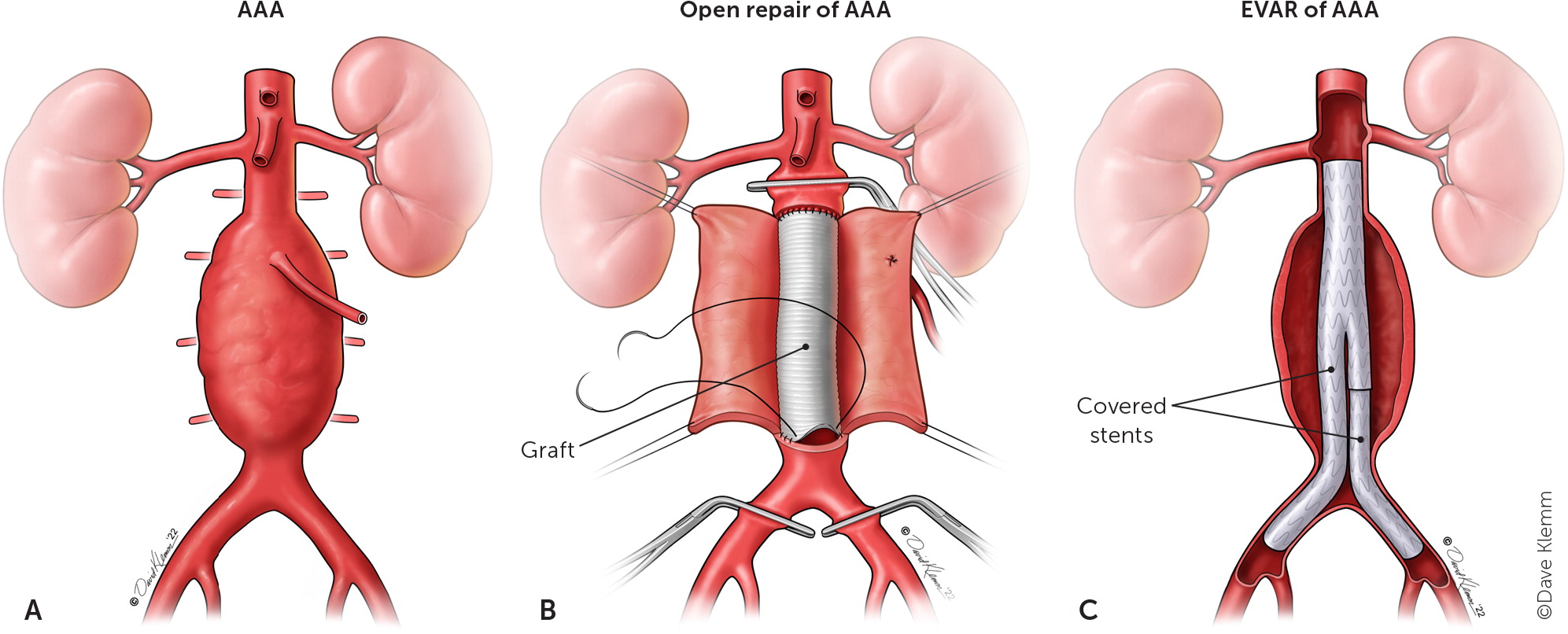

The incidence of rupture and the perioperative mortality of AAA have declined over the past two decades because of the technologic advancement with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and improvement of pre- and in-hospital care. Surgical repair of ruptured AAA is challenging, and most studies show that the perioperative mortality rates range from 40% to 60%.35 AAA can be managed using two types of surgical approaches: open repair and EVAR (Figure 4). Surgical management is indicated when the aneurysm diameter is 5.5 cm or larger for men and 5.0 cm or larger for women.

OPEN REPAIR

Traditional open repairs are done by a transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approach based on the patient's anatomy and surgeon preference.36 Bleeding control is crucial in ruptured and unruptured aneurysms during open repair. Therefore, surgeons usually place cross clamps on the proximal and distal parts of the aneurysm to adequately access and repair the aneurysmal sac.37 Open AAA repair with graft is very durable and has a low rate of late graft complications (0.4% to 2.3%).38 Imaging follow-up after an open repair is not required. A population-based observational study found that for patients who underwent open surgery for ruptured AAA and who survived the first 30 days, the survival rate is about 64% after five years and 33% after 10 years.39

ENDOVASCULAR ANEURYSM REPAIR

EVAR involves a small incision on the femoral vessels to gain vascular access to the aorta. A stent graft is deployed in the aneurysmal sac and extends into the iliac vessel. The purpose of the endograft is to decrease the pressure on the native aortic wall and prevent aneurysmal sac enlargement by excluding the aneurysm from circulatory pressures. An aortic stent graft must be reassessed at one month, six months, and then yearly to detect graft migration, evaluate for endoleaks, and monitor for expansion of the aortic aneurysmal sac.38

EVAR was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1999. Because of patient preference for EVAR compared with open repair, EVAR is the most common surgical repair for AAA.40 The long-term outcomes of EVAR vs. open repair are similar. In one EVAR randomized controlled trial (EVAR 1), EVAR demonstrated an early survival benefit, but an inferior late survival benefit compared with open repair.41 In a follow-up EVAR randomized controlled trial (EVAR 2), EVAR was compared with no repair in patients who were not eligible for open repair; it showed that EVAR does not improve life expectancy vs. no intervention, but it can reduce aneurysm-related mortality.42 The Dutch Randomised Endovascular Aneurysm Management trial found that EVAR and open repair of AAA resulted in similar rates of survival.31 Another randomized trial found that EVAR was associated with a lower risk of perioperative complications and death compared with open surgical repair, but the mortality was similar after two years.43 Studies suggest that EVAR is best suited for patients who are advanced in age or have serious comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or renal insufficiency, because these comorbidities are related to higher postoperative complications and death after open repair.38 Smoking cessation can be beneficial, and administration of pulmonary bronchodilators is recommended for patients with a history of symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or abnormal pulmonary function tests for at least two weeks before aneurysm repair.44

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Keisler and Carter.45

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms abdominal aortic aneurysm, diagnosis, pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. The Cochrane database and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and review articles. Search dates: June 10, 2021; July 5, 2021; August 3, 2021; August 6, 2021; and January 10, 2022.