Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):184-189

Patient information: See related handout on scrotal masses.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

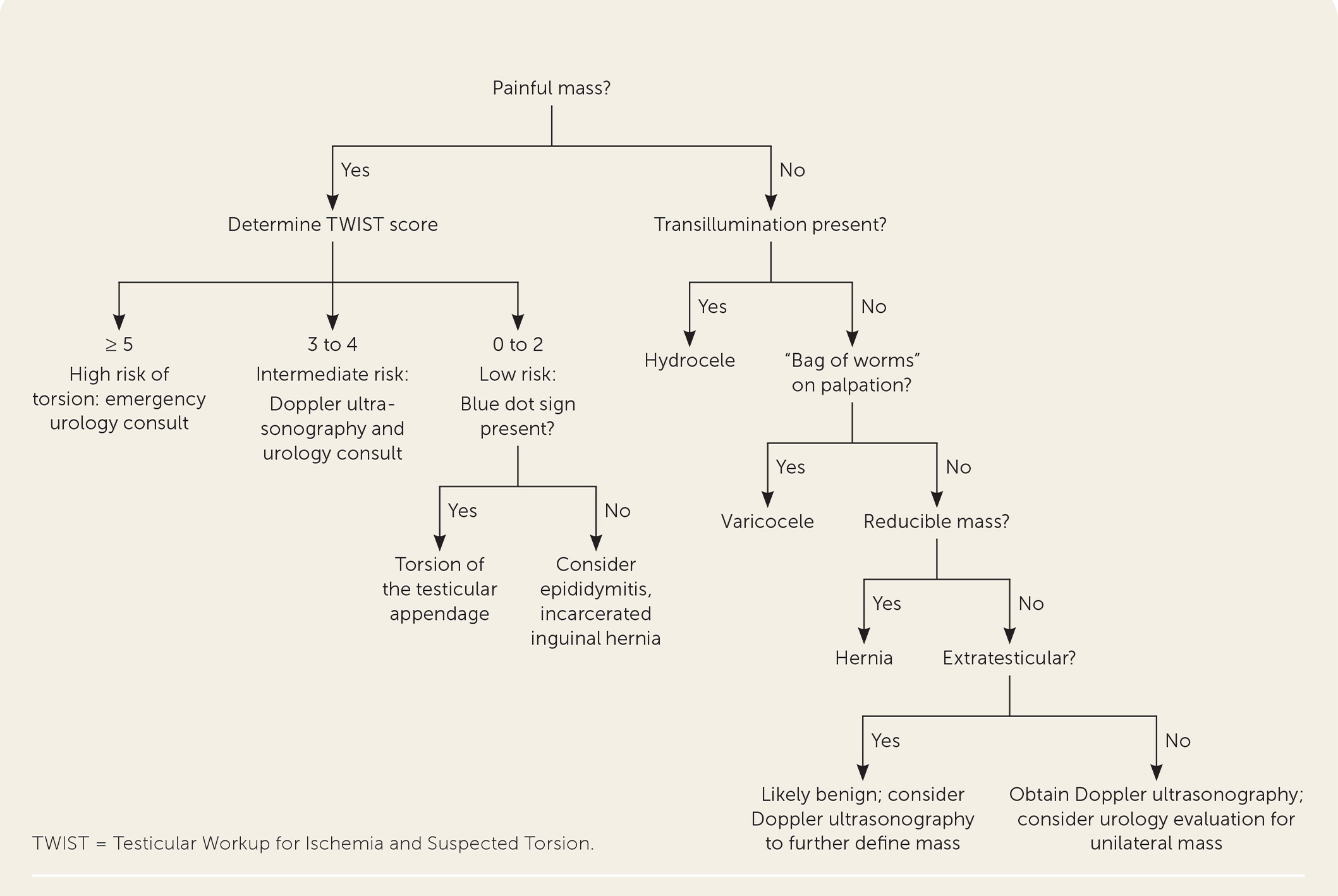

Scrotal and testicular masses can be broadly categorized into painful conditions, which include testicular torsion, torsion of the testicular appendage, and epididymitis, and painless conditions, which include hydrocele, varicocele, and testicular cancer. Testicular torsion is a urologic emergency requiring prompt surgical intervention to save the testicle, ideally within six hours of presentation when the salvage rate is about 90%. The Testicular Workup for Ischemia and Suspected Torsion score can be used to help physicians identify patients at high risk of torsion and those at lower risk who would benefit from imaging first. Torsion of the testicular appendage presents with gradual onset of superior unilateral pain, is diagnosed using ultrasonography, and is treated supportively with analgesics. Epididymitis is usually caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or enteric bacteria and is treated with antibiotics, analgesics, and scrotal support. Hydroceles are generally asymptomatic and are managed supportively. Varicoceles are also generally asymptomatic but may be associated with reduced fertility. It is uncertain if surgical or radiologic treatment of varicoceles in subfertile men improves the rate of live births. Testicular cancer often presents as a unilateral, painless mass discovered incidentally. Ultrasonography is used to evaluate any suspicious masses, and surgical treatment is recommended for suspected cancerous masses.

Scrotal and testicular masses can be broadly categorized into painful and painless presentations. Although this classification is useful, any condition discussed may cause discomfort, and the presence or absence of pain alone is insufficient to confirm or exclude a diagnosis. Family physicians should be familiar with the different types of scrotal masses to differentiate among conditions requiring emergent intervention, non-urgent treatment, and those that may be safely monitored. The anatomy of the scrotum is depicted in Figure 1.1

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not screen for testicular cancer in asymptomatic adolescent and adult males. | American Academy of Family Physicians |

Approach To Evaluation

In addition to the presence or absence of pain, patients should be asked about exacerbating and remitting factors, chronicity of symptoms, constitutional symptoms, abdominal pain, dysuria, and hematuria. The physical examination should include visual inspection and palpation of the testicles and spermatic cords for nodules or masses. An intact cremasteric reflex is present when pinching or stroking the inner thigh causes contraction of the cremaster muscle, pulling the ipsilateral testicle toward the inguinal canal; its absence may be associated with testicular torsion. If testicular pain improves with elevation of the testicle, this is a positive Prehn sign, which is associated with an increased risk of acute epididymitis. The inguinal canal should be palpated for evidence of a hernia. Fluid-containing masses such as hydroceles will transilluminate with a penlight.

Ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice for any suspected scrotal mass, and simultaneous Doppler imaging is used to confirm the presence or absence of adequate perfusion.2 Laboratory testing is generally restricted to cases of suspected infection or malignancy.

Painful Masses

Painful masses include testicular torsion, torsion of the testicular appendage, and epididymitis.

TESTICULAR TORSION

Testicular torsion is defined as a twisting of the spermatic cord around its longitudinal axis, causing venous congestion, reduced arterial blood flow, and eventual ischemia of the testicle. Torsion accounts for about 20% of childhood emergency department visits for acute scrotal pain.4 The incidence in males younger than 25 years is approximately one in 4,000, but torsion occurs most frequently in adolescence.5 Risk factors include a family history of torsion, a hyperactive cremasteric reflex in the setting of cold weather, antecedent trauma, and the bell-clapper deformity (excessive mobility of the testicle due to abnormal anchoring).6

Patients with torsion typically present with severe, acute, unilateral scrotal pain of less than 24 hours' duration accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and scrotal swelling.4 The affected testicle is usually high-riding and in transverse lie.4 Absence of the ipsilateral cremasteric reflex had an odds ratio of 47.6 for diagnosing torsion in one study.7 The Testicular Workup for Ischemia and Suspected Torsion score should be used during the initial evaluation of an acute scrotum to predict the risk of torsion (Table 1).8

| Score | Risk for torsion | Suggested management |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 5 | High | Urgent urologic consultation and surgical exploration |

| 3 to 4 | Intermediate | Ultrasonography, consider urologic consultation |

| 0 to 2 | Low | Ultrasonography and urologic consultation not required |

Urgent urologic consultation is recommended before imaging in cases with a high clinical suspicion of torsion.4 In intermediate-risk cases, high-resolution color Doppler ultrasonography is the test of choice to evaluate testicular blood flow, with an estimated sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 97.9% for detecting torsion.9

If the affected testicle is not necrotic and does not require removal, surgical detorsion and orchiopexy are the treatments of choice. Surgery should be done within six hours of presentation when the testicular salvage rate is approximately 90%.10 The salvage rate decreases significantly at 12 hours (50%) and 24 hours (10%).11 Bilateral orchiopexy is typically done to prevent torsion of the contralateral testicle in the future.6 Although manual detorsion can be attempted, it is not considered definitive treatment, and any attempt should not delay surgical evaluation and treatment.5

TORSION OF THE TESTICULAR APPENDAGE

The testicular appendage (also known as the appendix testis), which is present in approximately 85% of children, is a remnant of the müllerian duct located at the superior pole of the testicle.12 Torsion of the testicular appendage can present with gradual onset of intense unilateral superior scrotal pain without systemic symptoms. The blue dot sign, a bluish discoloration of the skin of the superior pole of the scrotum, is considered pathognomonic for torsion of the testicular appendage but is uncommonly observed.13 Doppler ultrasonography is recommended to exclude testicular torsion, and surgical exploration is required if the diagnosis is uncertain.2 Treatment is supportive with analgesics, and resolution usually occurs in one week.13

EPIDIDYMITIS

Acute scrotal pain may be due to inflammation of the epididymis (epididymitis), testicle (orchitis), or both (epididymo-orchitis). Epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis are managed identically. Epididymitis occurs much more frequently than orchitis, is a common cause of scrotal pain, and is usually the result of a bacterial infection14; orchitis is usually due to a viral infection such as mumps.15 Risk factors for epididymitis include amiodarone use, bicycle riding, obstruction of the bladder, prolonged sitting, trauma, and urogenital abnormalities.16

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are the most common causes of epididymitis among sexually active males 14 to 35 years of age and older men who practice insertive anal intercourse. In other males, enteric organisms such as Escherichia coli are the most common causative bacteria.16

Males with acute epididymitis usually present with gradually increasing unilateral scrotal pain, tenderness, dysuria, urinary frequency, palpable swelling of the epididymis, and a normal cremasteric reflex.16 A Prehn sign may be seen in acute epididymitis, but it has insufficient sensitivity to exclude other causes of unilateral scrotal pain, such as testicular torsion.17

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published recommendations for evaluation (Table 2) and treatment (Table 3) of acute epididymitis.18 All patients should receive supportive care, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bed rest, and scrotal elevation. If C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae is isolated, patients should be tested for other sexually transmitted infections and avoid sexual intercourse until they have completed treatment. Their sex partners from the previous 60 days should also be tested and treated.18

| Assess for inflammation using a point-of-care test |

| Any of the following is considered acceptable: |

| Gentian violet stain, Gram stain, or methylene blue stain of urethral secretions showing ≥ 2 white blood cells per oil immersion field |

| Positive leukocyte esterase test on first-void urine sample |

| Microscopic examination of sediment from a spun first-void urine sample demonstrating ≥ 10 white blood cells per high-power field |

| Suspected cases due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis infection |

| Obtain urine for nucleic acid amplification testing |

| Suspected cases due to enteric bacteria infection |

| Obtain urine culture |

| Characteristics | Recommended treatment |

|---|---|

| Most likely caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis | Ceftriaxone, 500 mg IM in a single dose (1,000 mg should be used for individuals who weigh 330 lb [150 kg] or more) and Doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 10 days |

| Most likely caused by N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, or enteric organisms among men who practice insertive anal intercourse | Ceftriaxone, 500 mg IM in a single dose (1,000 mg should be used for individuals who weigh 330 lb or more) and Levofloxacin (Levaquin), 500 mg orally once daily for 10 days |

| Most likely caused by enteric organism | Levofloxacin, 500 mg orally once daily for 10 days |

Painless Masses

Painless masses include hydroceles, varicoceles, spermatoceles, inguinal hernias, and testicular cancer.

HYDROCELES

A hydrocele is a collection of fluid that usually occurs between the layers of the tunica vaginalis and may communicate with the abdominal cavity.19 Hydroceles are typically painless, but large accumulations may be uncomfortable. In infants, hydroceles can be associated with inguinal hernias or undescended testicles, which require surgical repair.19 Isolated hydroceles in infants will often resolve within the first year of life without intervention.20 Hydroceles after infancy are often idiopathic but may also be associated with inflammatory conditions, injuries, or neoplasms.19,21 On physical examination, hydroceles feel smooth and fluctuant, are extratesticular, and will transilluminate.19 Ultrasonography is useful for diagnosis and classification and to exclude other pathology that might not be palpable because of the hydrocele.2 Patients with symptomatic or communicating hydroceles should be referred to a urologist for definitive treatment.19

VARICOCELES

A varicocele is abnormal dilation of the pampiniform plexus, either caused by incompetence of the gonadal vein valves or external compression of the gonadal vein.22 They more commonly occur on the left side due to drainage into the high-pressure left renal vein. Isolated right-sided varicoceles should prompt an evaluation for a retroperitoneal mass because venous drainage on the right is into the inferior vena cava.22 Patients with large varicoceles may report dull pain or scrotal heaviness. Varicoceles are found in approximately 15% of men, but prevalence increases to 35% in men with primary infertility and up to 80% in men with secondary infertility.22 Examination should be performed with the patient standing. Varicoceles are classically described as a “bag of worms” and increase in size when the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. Ultrasonography can be used to confirm the diagnosis.21 Most varicoceles do not require treatment. A 2021 Cochrane review concluded that it was uncertain if surgical or radiologic treatment of varicoceles in subfertile men improves the rate of live births.23

INGUINAL HERNIAS

Inguinal hernias usually can be diagnosed on history and physical examination when the examiner's finger is placed into the inguinal canal and the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. Evaluation and treatment of inguinal hernias are discussed in a previous American Family Physician article.24

TESTICULAR CANCER

Testicular cancer is the most common solid tumor diagnosed in men between 15 and 34 years of age, and usually presents as a firm, unilateral nodule that is often but not necessarily painless. An estimated 8,850 men are diagnosed in the United States annually, with 410 deaths per year.25 Risk factors include an undescended testicle, a personal or family history of testicular cancer, HIV infection, and carcinoma in situ of the testis. Testicular cancer is four to five times more common in White males compared with Black or Asian American males.26 Ultrasonography is recommended for men with solid testicular masses, and has a reported sensitivity of 92% to 98% and a specificity of 95% to 99.8% for detecting cancer.27 Laboratory studies for suspected cancer include a comprehensive metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase, and the tumor markers alpha fetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin.26 Patients should be urgently referred to a urologist for treatment, which is generally a radical orchiectomy following counseling concerning the potential for hypogonadism and infertility.26 Follow-up treatment and surveillance are done with a multidisciplinary team.26

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening for testicular cancer in asymptomatic average-risk adolescents and adult men because of the low prevalence of the disease and the high cure rates even in advanced cases.28 The American Cancer Society has no screening recommendation for asymptomatic men.29

OTHER MASSES

Epididymal cysts and spermatoceles (dilation of the efferent epididymal ductules) are benign lesions that may be palpated in the spermatic cord. Spermatoceles occur more commonly in men who have had a vasectomy.30 Ultrasonography is recommended to confirm the diagnosis.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Crawford and Crop,3 Tiemstra and Kapoor,1 and Junnila and Lassen.31

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms scrotal mass, acute scrotum, testicular cancer, and imaging scrotum. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Search dates: September 2021 through April 2022.