Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(1):71-78

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Infectious mononucleosis is a viral syndrome characterized by fever, pharyngitis, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. It is usually caused by Epstein-Barr virus and most often affects adolescents and young adults 15 to 24 years of age. Primary transmission is through close personal contact with a person who is infected, particularly their saliva. Cost-effective, efficient initial laboratory testing for acute infectious mononucleosis includes complete blood count with differential (to assess for greater than 40% lymphocytes and greater than 10% atypical lymphocytes) and a rapid heterophile antibody test. The heterophile antibody test has a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 91% but can have a false-negative result in children younger than five years and in adults during the first week of illness. The presence of elevated liver enzymes increases clinical suspicion for infectious mononucleosis in the setting of a negative heterophile antibody test result. Epstein-Barr viral capsid antigen-antibody testing is more sensitive and specific but more expensive and takes longer to process than the rapid heterophile antibody test. Treatment of infectious mononucleosis is supportive; routine use of antivirals and corticosteroids is not recommended. Current guidelines recommend that patients with infectious mononucleosis not participate in athletic activity for three weeks from onset of symptoms. Shared decision-making should be used to determine the timing of return to activity. Immunosuppressed populations are at higher risk of severe disease and significant morbidity. Epstein-Barr virus infection has been linked to nine types of cancer, including Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and some autoimmune diseases.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Avoid ordering abdominal ultrasonography routinely in athletes with infectious mononucleosis. | American Medical Society for Sports Medicine |

Epidemiology

Most cases of infectious mononucleosis are caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), although approximately 10% of cases are caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV).2–4 Other viruses, such as human herpesvirus 6, adenovirus, and herpes simplex, can cause an illness similar to mononucleosis.

Infection with EBV is most common in childhood and adolescence, and males and females are affected equally.5 Studies show that two-thirds of children and adolescents six to 19 years of age in the United States and more than 95% of adults 20 to 25 years of age in the United Kingdom are seropositive.6–8

In wealthier nations, infectious mononucleosis mostly affects adolescents and young adults 15 to 24 years of age (6 to 8 cases per 1,000 person-years), particularly those living in communal environments, such as dormitories or military barracks (11 to 48 cases per 1,000 person-years).2

Transmission

The primary mode of disease transmission is through close personal contact with a person who is infected, particularly their saliva, including sharing eating utensils or water bottles, kissing, or through sexual intercourse.1,9,10

The incubation period for EBV infection is 32 to 49 days, during which the patient is contagious.1 Viral replication is first detected in the oral cavity and has also been isolated in genital secretions.1,9

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis is presented in Table 1.11

Hoagland criteria, which are often used to aid in the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis, include greater than 50% lymphocytes and 10% atypical lymphocytes in the presence of fever, pharyngitis, and adenopathy, with confirmatory serologic testing.3,12

Hoagland criteria are specific but not sensitive for mononucleosis.13

Laboratory testing is crucial in confirming infectious mononucleosis.2,14

| Diagnosis | Key distinguishing features |

|---|---|

| Acute HIV infection | Mucocutaneous lesions, rash, weight loss, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting |

| Other viral pharyngitis | Throat pain; fever, adenopathy, and tonsillar exudate are less likely |

| Streptococcal pharyngitis | Throat pain without hepatomegaly or splenomegaly; fatigue is less prominent |

| Toxoplasmosis | Recent history of eating undercooked meat or cleaning a cat's litter box; toxoplasmosis can cause a false-positive heterophile antibody result; therefore, immunoglobulin M serology should be used for diagnosis |

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Table 2 shows the accuracy of symptoms and signs in the diagnosis of clinically suspected infectious mononucleosis.15

Common symptoms include pharyngitis, malaise, loss of appetite, fatigue, and upper respiratory tract symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhea, nasal congestion). Abdominal pain may occur.10

Tonsillar exudate is seen in 50% of people with infectious mononucleosis. Palatal petechiae are more suggestive of infectious mononucleosis but are less common than tonsillar exudate and may also be seen in streptococcal pharyngitis.15 Tonsillar inflammation is nonspecific.

Infectious mononucleosis classically presents as posterior cervical lymphadenopathy; however, axillary and inguinal lymphadenopathy are also common and help distinguish infectious mononucleosis from other types of infectious pharyngitis.14,15 A recent meta-analysis found that the sign or symptom that most strongly predicts infectious mononucleosis is posterior cervical lymphadenopathy (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] = 3.2).15

Less than 5% of those with infectious mononucleosis present with a maculopapular, urticarial, or petechial rash.16 The rash usually occurs with recent amoxicillin use.

Splenic enlargement is nearly universal in infectious mononucleosis.17 Physical examination is unreliable for identifying splenomegaly and has a wide range of sensitivity (20% to 70%) and specificity (69% to 100%).14

Children younger than five years often present with fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy but are more likely than adolescents and adults to present with rash, palpable splenomegaly, and upper respiratory tract symptoms.18

Patients with HIV infection can develop secondary conditions caused by EBV, including lymphadenopathy, atypical lymphoproliferation, and malignant transformations of lymphoid, muscle, and epithelial cells.19

| Symptoms and signs | Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | Diagnostic odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | |||||

| Nausea or vomiting | 30 (22 to 39) | 72 (34 to 93) | 1.9 (0.54 to 6.0) | 0.99 (0.63 to 1.24) | 2.4 (0.25 to 9.3) |

| Pharyngitis* | 81 (68 to 90) | 25 (17 to 35) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 0.67 (0.41 to 1.01) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.0) |

| Headache* | 59 (40 to 76) | 37 (23 to 54) | 1.2 (1.01 to 1.4) | 0.72 (0.50 to 0.98) | 1.7 (1.03 to 2.8) |

| Malaise or fatigue | 72 (59 to 82) | 24 (11 to 43) | 1.0 (0.91 to 1.2) | 0.99 (0.67 to 1.48) | 1.09 (0.62 to 1.7) |

| Myalgias or arthralgias | 23 (9 to 49) | 39 to 59 | 0.45 to 1.35 | 0.47 to 1.39 | 0.34 to 2.8 |

| Sign | |||||

| Posterior cervical lymphadenopathy* | 67 (51 to 80) | 87 (84 to 89) | 3.2 (1.4 to 5.2) | 0.68 (0.41 to 0.93) | 5.2 (1.6 to 12.6) |

| Axillary or inguinal lymphadenopathy* | 23 (9 to 47) | 82 to 91 | 3.0 (1.85 to 4.7) | 0.67 (0.36 to 0.91) | 5.0 (2.1 to 10.5) |

| Splenomegaly* | 45 (20 to 73) | 74 (30 to 95) | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.5) | 0.66 (0.5 to 0.84) | 3.6 (1.4 to 7.8) |

| Tonsillar exudate* | 47 (30 to 64) | 78 to 84 | 1.4 to 4.1 | 0.23 to 0.93 | 1.5 to 17 |

| Palatal petechiae* | 14 (6 to 28) | 94 to 100 | 1.3 to 11.4 | 0.57 to 0.94 | 1.5 to 155 |

| Anterior cervical lymphadenopathy | 74 (59 to 85) | 43 (39 to 47) | 1.27 (0.8 to 1.6) | 0.65 (0.25 to 1.3) | 2.5 (0.63 to 6.2) |

| Any lymphadenopathy* | 93 (86 to 97) | 21 (7 to 49) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 0.37 (0.2 to 0.67) | 3.8 (1.6 to 7.6) |

| Fever (> 99.5°F [37.5°C]) | 64 (37 to 84) | 46 (17 to 79) | 1.2 (0.91 to 1.8) | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.3) | 1.45 (0.67 to 2.7) |

INITIAL DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The accuracy of diagnostic laboratory testing for infectious mononucleosis is presented in Table 3.11,15

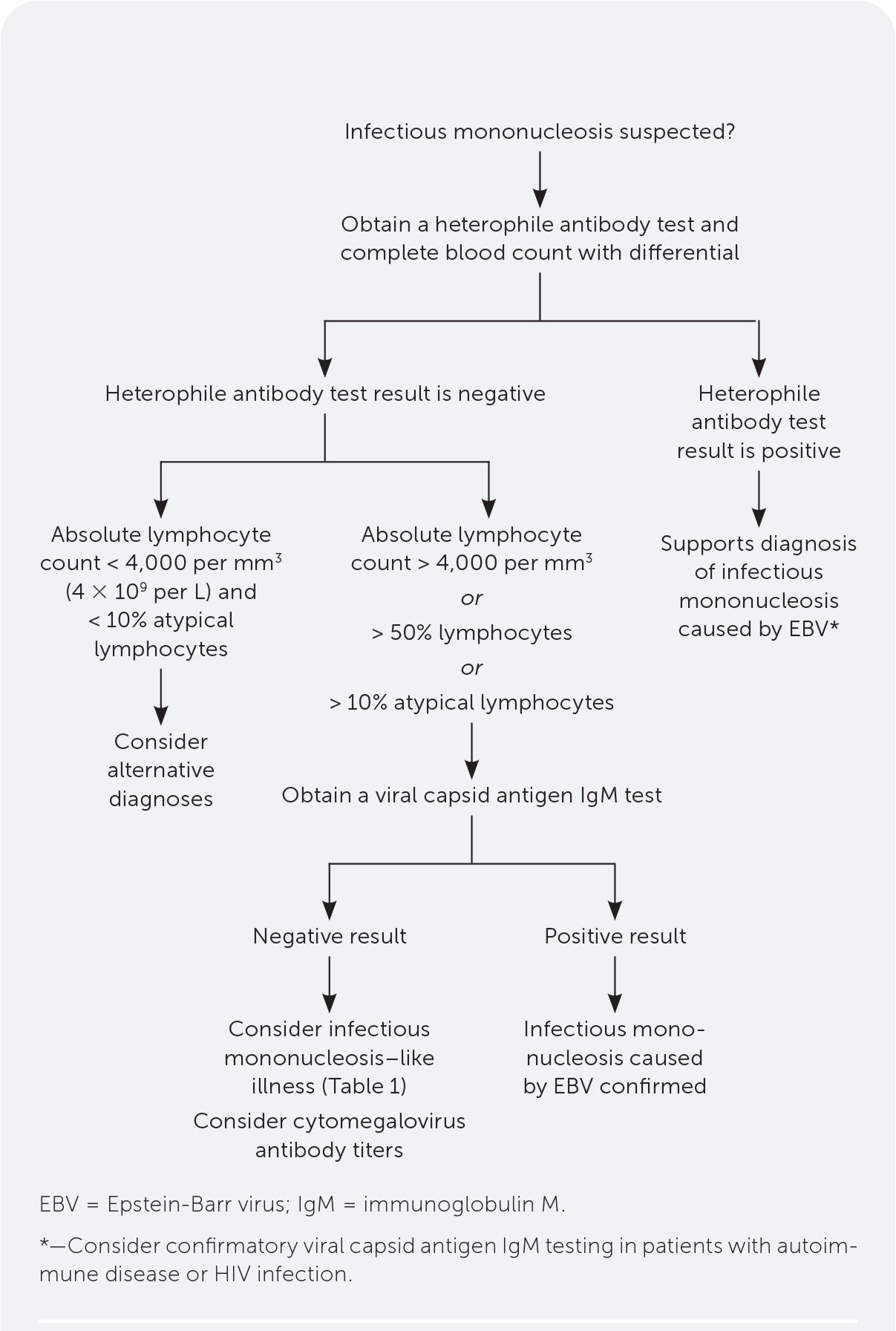

Initial testing for acute infectious mononucleosis should include complete blood count with differential and a rapid heterophile antibody test.2,14,20,21 Testing for streptococcal pharyngitis should be considered if indicated.

Parameters for atypical lymphocytes that strongly suggest infectious mononucleosis are greater than 10% (LR+ = 9.0), greater than 20% (LR+ = 28), and greater than 40% (LR+ = 50).15

The heterophile antibody latex agglutination test (monospot) is an inexpensive, rapid test with 87% sensitivity and 91% specificity reported in a systematic review.20 However, the study design likely resulted in higher sensitivity and specificity than would be seen in routine office practice, especially early in the disease course.

Heterophile antibody testing has limitations, including false-negative results in up to 25% of adults in the first week of symptoms3; high false-negative rates in children younger than five years2,21; and persistence of positive results for up to one year following initial EBV infection.22 Other conditions can cause false-positive results, including autoimmune diseases, viral hepatitis, and HIV infection.23

The absence of atypical lymphocytosis supports the accuracy of a negative heterophile antibody test result.

Hospitalized patients with infectious mononucleosis have been shown to have increased hepatic transaminase levels.24–26 Smaller outpatient studies showed more variable data; 58% to 100% of patients with infectious mononucleosis have elevated liver enzymes.27,28 The presence of elevated liver enzymes increases clinical suspicion for infectious mononucleosis in the setting of a negative heterophile antibody test result.

| Findings | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 50% lymphocytes and > 10% atypical lymphocytes | 45 | 99 | 51 | 0.58 |

| > 40% atypical lymphocytes | 25 | 100 | 50 | 0.75 |

| > 20% atypical lymphocytes | 56 | 98 | 28 | 0.45 |

| > 10% atypical lymphocytes | 55 | 94 | 9.0 | 0.48 |

| > 50% lymphocytes | 56 | 93 | 8.5 | 0.49 |

| > 40% lymphocytes | 74 | 86 | 5.3 | 0.30 |

| Heterophile antibody latex agglutination* | 87 | 91 | 9.7 | 0.14 |

| Antibody to EBV viral capsid antigen or EBV-associated nuclear antigen* | 97 | 94 | 16 | 0.03 |

FOLLOW-UP LABORATORY EVALUATION

Viral capsid antigen (VCA) immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM testing can be helpful if heterophile antibody test results are negative but clinical suspicion is high. VCA testing is more specific and sensitive than heterophile antibody testing, although it is more expensive and takes longer to process.14

VCA IgM is an early marker of infection and remains present for four to six weeks. VCA IgG appears two weeks after infection and persists for life. EBV nuclear antigen IgG antibodies typically become detectable six to eight weeks after infection.13

VCA IgM without EBV nuclear antigen antibodies is indicative of primary EBV infection. VCA IgG with EBV nuclear antigen antibodies suggests past infection.14

VCA testing may be helpful when accurate diagnosis is particularly important, such as in competitive athletes and pregnant patients.

Symptoms of primary CMV mononucleosis are almost indistinguishable from those of infectious mononucleosis caused by EBV. Positive IgM serology is the best way to diagnose CMV (heterophile-negative) mononucleosis.

Figure 1 illustrates a laboratory-based approach for the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis.29

IMAGING STUDIES

Routine imaging is not indicated in the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis.14

Ultrasonography is a reliable method for detecting and characterizing splenic enlargement.30,31 However, splenic enlargement occurs in nearly all patients with infectious mononuclesosis.17,32

Splenic injury is a rare but serious complication of infectious mononucleosis and should be considered in patients with the disease who have acute or worsening abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the preferred modality for detecting splenic injury.33

Treatment

Treatment of infectious mononucleosis is supportive, with surveillance for potential complications.2,14 Maintaining adequate hydration is important.14

Exercise is contraindicated because any exertion may cause splenic rupture.14 Current guidelines recommend three weeks of exercise restriction.14

Judicious use of acetaminophen should be considered for symptomatic relief of fever and pharyngitis.14 Patients should avoid excessive use of alcohol, acetaminophen, and other hepatotoxic medications. Aspirin should be avoided in children and adolescents.14

A Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to support the use of corticosteroids in patients with uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis.34 Corticosteroids can be considered in patients with airway obstruction and severe disease.

Another Cochrane review showed insufficient evidence to recommend routine use of antivirals in patients with uncomplicated infectious mononucleosis.35

Routine use of antibiotics is not warranted but may be considered in patients with concurrent streptococcal pharyngitis.14 Use of beta-lactam antibiotics, particularly amoxicillin, within the 10 days preceding symptoms causes a maculopapular exanthem in 90% to 100% of patients.16

Prognosis and Complications

Infectious mononucleosis is typically self-limited, with symptoms lasting for three days to eight weeks.36,37 Some patients report persistent fatigue for six months or longer.38

Hospitalization occurs in less than 1% of cases. In a French observational study, 38 patients were hospitalized for acute infectious mononucleosis complications over 14 years, including severe hepatitis (n = 12), severe dysphagia or airway obstruction (n = 15), and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (n = 5).36

Splenic injury occurs in 0.1% to 0.2% of people with infectious mononucleosis. These injuries are usually nontraumatic (80% to 86%) and have up to a 9% mortality rate.32,42 Most cases of splenic rupture occur within 21 days of symptom onset (73.8%), with 90% occurring by day 31.32 However, splenic ruptures have been diagnosed up to eight weeks after onset of illness.42

EBV infection can lead to severe and potentially fatal complications in patients with immunodeficiency, including X-linked lymphoproliferative disease.43 Transplant recipients are at increased risk of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in the setting of EBV infection, with a 50% mortality rate.44

EBV has been linked to two pre-malignant lymphoproliferative diseases and nine types of cancer.40 In the United States, EBV has been associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.41

Evidence suggests that prior EBV infection increases the risk of autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis.21,45 A recent large, prospective case-control study of U.S. military personnel found that those with prior EBV infection were 32 times more likely to develop multiple sclerosis.45

| Acute interstitial nephritis Hemolytic anemia Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Meningoencephalitis Myocarditis and cardiac conduction abnormalities | Severe dysphagia Severe hepatitis Splenic rupture Thrombocytopenia Upper airway obstruction (more common in young children) |

Return to Athletic Activity

Current guidelines advise restricting all athletic activity for three weeks following symptom onset to reduce the risk of splenic rupture. Athletes should feel clinically well and be afebrile before returning to sports. Resumption of athletic activity should be gradual, starting with light, noncontact activity.14

Shared decision-making is crucial in determining the timing of return to activity, particularly contact sports.

There is no strong evidence to support the use of ultrasonography in expediting the patient's return to sports.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Ebell11 and Womack and Jimenez.29

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms mononucleosis, infectious mononucleosis, and Epstein-Barr virus. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Cochrane database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: December 13, 2021, and September 20, 2022.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Department of Defense, or U.S. government.