This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(3):253-262

Patient information: See related handout on glaucoma, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Glaucoma is a group of eye disorders characterized by progressive deterioration of the optic nerve that can lead to vision loss. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form in the United States. The risk of POAG increases with age, family history of glaucoma, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypotension, hypothyroidism, obstructive sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, and myopia. Up to one-half of patients are undiagnosed because a diagnosis often requires monitoring over years to document changes suggesting POAG. These include a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3 or greater, intraocular pressure greater than 21 mm Hg on tonometry, nerve fiber layer defects identified on optical coherence tomography, and reproducible visual field defects. Topical intraocular pressure–lowering medications and selective laser trabeculoplasty are first-line treatments for POAG. Although POAG screening in the general adult population is not recommended, primary care physicians can help decrease POAG-related vision loss by identifying patients with risk factors and referring them for evaluation by an eye specialist. Medicare covers evaluations in patients at high risk. Primary care physicians should encourage medication adherence and identify barriers to treatment. The other type of glaucoma is angle-closure glaucoma, in which the flow of aqueous humor is obstructed. Angle-closure glaucoma can occur acutely with pupillary dilation and is an ophthalmologic emergency. The goal of treatment for acute angle-closure glaucoma is to reduce intraocular pressure quickly with medications or surgery, then prevent the recurrence of the obstruction to aqueous flow by a definitive ophthalmologic procedure.

Glaucoma is a group of eye disorders characterized by progressive deterioration of the optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber layer (i.e., the portion of the optic nerve that runs through the retina). Without treatment, this neural deterioration can result in vision loss.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing intraocular pressure is the only treatment proven to stop or slow the progression of vision loss in primary open-angle glaucoma.3,5,9,18,24,25 | A | Multiple randomized controlled trials, practice guidelines, and a Cochrane review |

| Selective laser trabeculoplasty is a first-line treatment for primary open-angle glaucoma.28 | B | Multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing selective laser trabeculoplasty with standard medical therapy for patients with primary open-angle glaucoma |

| There is insufficient evidence to recommend screening for glaucoma in the general adult population.5,9 | C | U.S. Preventive Services Task Force evidence review and practice guidelines from the American Academy of Ophthalmology |

| Primary care physicians should ask patients about barriers to adhering to their glaucoma medication and encourage the use of automated reminders.3,34,35 | C | Narrative reviews and cohort studies |

There are two forms of glaucoma: primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), in which the outflow tract is anatomically open, and angle-closure glaucoma (ACG), in which the outflow of aqueous humor from within the eye is obstructed.1–5 POAG in adults is the focus of this article because it is the most common form of glaucoma in the United States.1–3 Table 1 provides a glossary of terms related to the evaluation and treatment of patients with glaucoma.1–6

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Glaucoma suspect | Patients with eye findings that could indicate an increased risk of developing glaucoma; includes patients with an elevated intraocular pressure and a normal optic disc, retinal nerve fiber layer, and visual fields; may also include patients with an isolated suspicious optic nerve head (i.e., large cup-to-disc ratio > 0.3), retinal nerve fiber layer, or visual fields without elevated intraocular pressure |

| Gonioscopy | Measuring the angle between the iris and cornea using special lenses and slit lamp (http://www.gonioscopy.org/basic-exam-techniques.htm) |

| Lamina cribrosa | Highly organized, sieve-like structure at the opening in the sclera through which axons of the retinal ganglion cells pass from the retina to form the optic nerve; there are hundreds of openings through which roughly 1 million to 2 million nerve fibers, grouped into bundles, exit the eye, and when these axons bend and pass through the lamina cribrosa, they are sensitive to damage |

| Neuroretinal rim | Dense packing of nerve fibers and glial cells inside the optic disc, usually pink in color; damage with loss of the cells results in thinning of the rim, which is a cardinal feature of glaucoma; this thinning can happen diffusely, making the central portion of the optic disc (optic cup) appear larger, or focally, which appears as notching on the side of the rim |

| Ocular hypertension | Elevated intraocular pressure; greater than 21 mm Hg |

| Optic disc/optic nerve head | Oval structure in the posterior fundus where axons of retinal ganglion cells converge and exit the eye; some distinguish the optic nerve head as the three-dimensional structure where this occurs, whereas others use these terms interchangeably |

| Optical coherence tomography | Technique to provide cross-sectional images of the retina by measuring and analyzing patterns of reflected infrared light; this is analogous to ultrasonography using sound waves to visualize biologic structures and enables detailed, quantitative information about the optic nerve head, retinal nerve fiber layer, and other structures (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554044/figure/ch3.Fig15) |

| Pachymetry | Measuring corneal thickness; patients with thinner corneas are at higher risk of developing glaucoma |

| Perimetry | Visual field testing; can be performed roughly by confrontation; most often done by automatic static perimetry in which the patient pushes a button when a light stimulus is presented somewhere in their visual field (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npwVkITgvKQ) |

| Physiologic cup | Short, funnel-shaped depression at the center of the optic nerve, where vessels can be viewed; typically paler than the surrounding neuroretinal rim; enlargement in the cup (i.e., cupping) is a cardinal feature in glaucoma; progressive cupping of the optic disc is a result of compression, stretching, and remodeling of the connective tissue of the lamina cribrosa; the cup-to-disc ratio is the vertical diameter of the cup expressed as a fraction of the vertical diameter of the disc, which is abnormal if > 0.3 |

| Tonometry | Measurement of intraocular pressure; most commonly done by applanation tonometry, where intraocular pressure is determined by measuring the force required to flatten a portion of the cornea; indentation tonometry measures the force required to press into the cornea; primary care tonometry can be performed with a tonometer (requires topical anesthetic) or iCare |

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

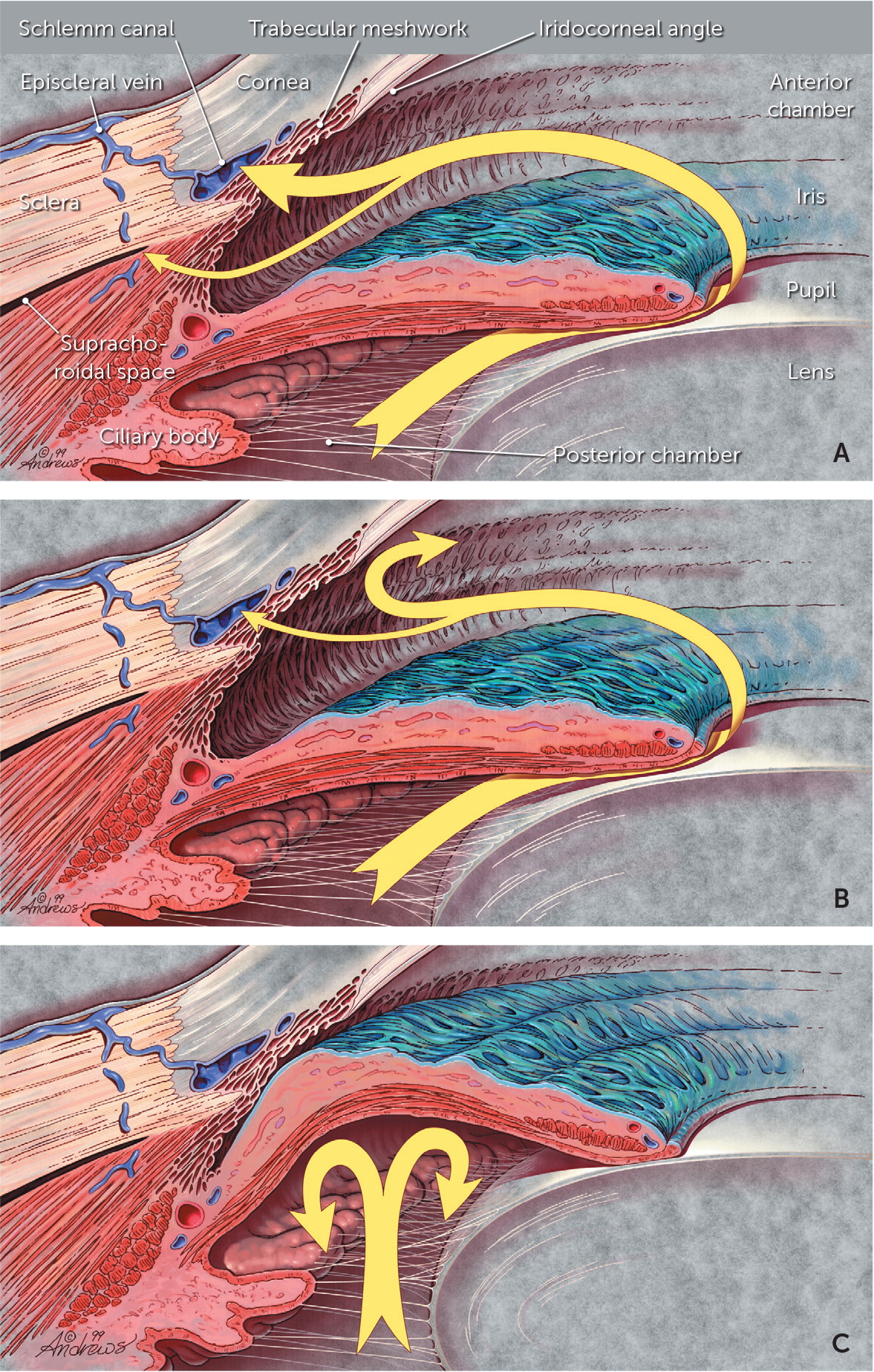

Aqueous humor is produced by the ciliary body and flows through the pupil and into the anterior chamber (Figure 1).7 The fluid drains primarily through the trabecular meshwork into the venous circulation. The balance between the rate of aqueous humor production and the rate of outflow determines intraocular pressure (IOP). Normal IOP varies with blood pressure, respiration, and time of day (lower in the evening).1–4

An elevated IOP is an important risk factor for glaucoma and can damage retinal cell axons when they pass out of the eye to form the optic nerve.1–10 However, some patients have a normal IOP and develop glaucomatous eye damage anyway. There are also patients with an elevated IOP who never develop eye damage; therefore, the pathophysiology of glaucoma is only partially understood.

The cause of POAG is multifactorial. The biomechanical theory states that there is resistance to aqueous outflow even though no obstruction is clinically identifiable, and the resulting IOP elevation directly damages the optic nerve head. The vascular theory states that decreased blood flow in vessels surrounding the optic nerve head results in ischemic damage. In the neurodegenerative theory, the cause is the primary deterioration of the optic nerve head, possibly due to autoimmunity, loss of neurotrophic factors, or failure of cellular repair mechanisms. An association with dementia has been noted in support of a neurodegenerative etiology.2,3,5,11

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Glaucoma is second only to cataracts as the top cause of blindness worldwide and is the leading cause of blindness among people of African descent in the United States. The estimated prevalence of glaucoma in people older than 40 years is 3.5%, which increases with age. This prevalence is expected to increase from approximately 60 million people worldwide to 112 million by 2040 (estimates for the United States are 3 million and are expected to increase to 6 million by 2050). Up to 50% of people with glaucoma are undiagnosed, and this proportion is likely higher in medically underserved populations.4,12

POAG accounts for approximately 75% of glaucoma cases in the United States.4,12 The prevalence of POAG in people of African and Hispanic descent in the United States is at least threefold higher than in non-Latino White people.2,3,5,13,14 The reasons behind this association are unclear and complex, and warrant more study because there are also socioeconomic factors that influence access to care and the detection and treatment of glaucoma.5,15–17

RISK FACTORS

The most important risk factor for developing POAG is an elevated IOP (i.e., ocular hypertension), usually defined as pressure above 21 mm Hg. Approximately 10% of patients with an elevated IOP develop glaucoma after five years, and 30% at 20 years. Although the risk of glaucoma progression is directly related to the degree of elevation of IOP, up to 40% of patients with glaucoma have normal IOP at initial diagnosis, and about 5% of people in the United States have ocular hypertension without glaucoma.2,5,18

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

POAG usually progresses slowly from normal vision to blindness over 25 years, although there is significant individual variation, and most patients with glaucoma do not go blind.19 Approximately 50% of people with glaucoma are unaware of their condition because visual symptoms are minimal until the disease is advanced.2,5 POAG should be suspected when a patient’s history shows past eye trauma or ocular surgery, corticosteroid use, a family history of glaucoma, or certain medical conditions (Table 22,3,5).

| Disease type | Medical conditions |

|---|---|

| Endocrine | Cushing disease Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| Inflammatory/infectious | Herpetic disease Lyme disease Rheumatoid arthritis Sarcoidosis Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Other | Migraine Obstructive sleep apnea Sickle cell disease |

PRESENTATION

Patients typically have no symptoms early in the course of POAG; however, blind spots may develop over time, and there can be a loss of contrast sensitivity, which is the ability to distinguish small objects without a clear outline from their background. Decreased central vision occurs late in the disease.

DIAGNOSIS

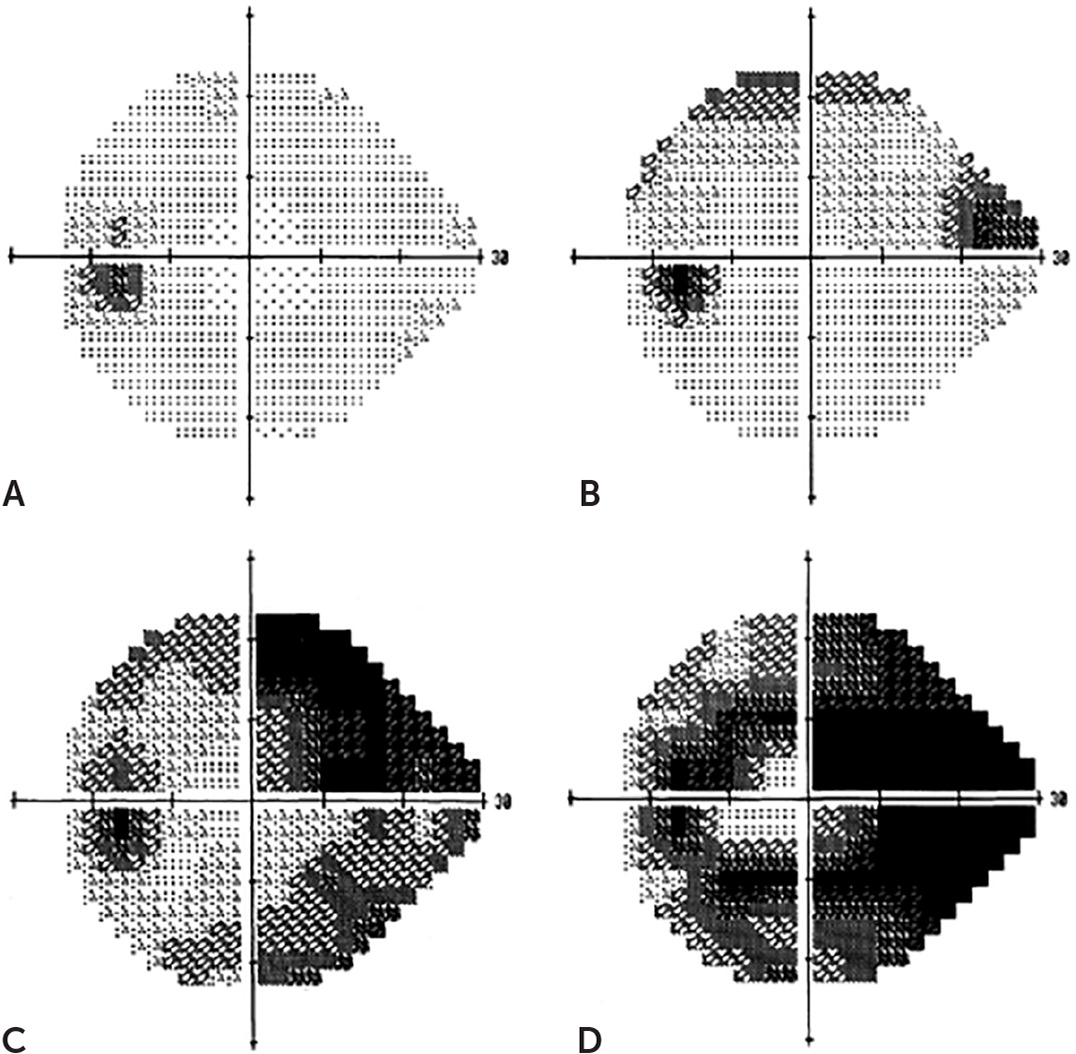

Visual field testing is also used for diagnosis, but it is not a sensitive indicator of early glaucoma because visual field defects typically do not occur until up to 50% of the retinal ganglion cells are lost. Visual field loss starts most often in the periphery and advances centrally as the disease progresses1–3,5,23 (Figure 37).

The diagnosis of glaucoma typically requires an eye specialist who follows the patient over time because of the lack of specific and sensitive findings early in the disease course. A comprehensive eye evaluation includes a dilated retinal examination with applanation tonometry, gonioscopy, a slit-lamp examination, measurement of corneal thickness (pachymetry), and a visual field test using an automated perimeter (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npwVkITgvKQ).

Another important test is optical coherence tomography, a noninvasive imaging technique used by eye specialists. Optical coherence tomography evaluates light reflected from ocular tissues to evaluate the anatomy of the optic nerve head, macula, and retinal nerve fiber layer. Thinning in the retinal nerve fiber layer typically occurs before the development of functional losses is detectable by visual field testing.1,2,5 Serial thinning of the optic nerve on optical coherence tomography is a characteristic of glaucoma.

The initial diagnosis of POAG is presumptive, and observations over years are a more accurate indicator of the disease. Persistent or worsening findings of a 0.3 or greater cup-to-disc ratio, increasing IOP greater than 21 mm Hg, nerve fiber layer defects verified with optical coherence tomography, and reproducible visual field defects all substantiate the diagnosis. The eye specialist should exclude conditions in the differential diagnosis, such as ischemic, toxic, congenital, demyelinating, and compressive causes of optic neuropathy.1,2,5,8

TREATMENT WITH TOPICAL MEDICATIONS

Reducing IOP is the only treatment proven to stop or slow the progression of vision loss in POAG.3,5,9,18,24,25 The decision to start treatment and determine the target IOP is individualized and depends on the status of the optic nerve, retinal nerve fiber layer, and rate of progression instead of the actual pressure measurement.5 In the absence of abnormalities, not all patients with ocular hypertension require treatment. Risk calculators can help guide decisions about who should be treated (https://ohts.wustl.edu/risk).

| Class | Mechanism of action | Reduction in intra-ocular pressure | Dosing*/cap color | Local adverse effects | Systemic adverse effects | Contraindications/drug interactions | Agents | Cost† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostaglandin analogues | Increase uveoscleral outflow | 25% to 35% | Once daily/teal cap | Hyperemia, burning, stinging, itching, foreign body sensation, eye pain, iris pigmentation, eye-lash lengthening, periocular skin hyperpigmentation | Rare; dyspnea, asthma are the most common | Active uveitis No interactions reported | Bimatoprost (Lumigan) Durysta (one intraocular implant) Latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta‡) Tafluprost (Zioptan) Travoprost (Travatan Z) | $26 ($230) $1,900 – ($450) – ($170) $40 ($200) |

| Beta blockers | Decrease aqueous production | 20% to 25% | Twice daily§/yellow cap | Corneal hypesthesia, burning, stinging | Cardiopulmonary, hallucinations, fatigue, malaise; can mask hypoglycemia | Severe asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bradycardia (heart rate < 55 beats per minute), second- and third-degree heart block; uncontrolled heart failure High doses of systemic beta blockers, digoxin, quinidine, diltiazem, verapamil | Betaxolol (Betoptic S) Carteolol Levobunolol (Betagan) Timolol (Timoptic) | $15 ($325) $10 $12 (−) $5 ($220) |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | Decrease aqueous production | 15% to 20% | Three times daily/orange cap | Burning, stinging, bitter taste, punctate keratitis | Few, if any, systemic adverse effects | Sickle cell disease, use caution in patients with sulfa allergy | Brinzolamide (Azopt) Dorzolamide (Trusopt) | $130 ($360) $85 ($85) |

| Alpha-adrenergic agents | Decrease aqueous production and increase outflow | 20% to 25% | Three times daily/purple cap | Burning, stinging | Dry mouth | Fatigue, drowsiness, hypotension Sedatives (especially midazolam), hydrocodone, monoamine oxidase inhibitors | Apraclonidine (Iopidine) Brimonidine (Alphagan P) | $30 ($180) $5 ($190) |

| Rho-kinase inhibitors | Increase aqueous outflow, decrease episcleral venous pressure | 10% to 20% | Once daily/white cap | Conjunctival hyperemia, blurred vision, cornea verticillata, keratitis | None reported | Active uveitis No interactions reported | Netarsudil (Rhopressa) | – ($300) |

| Parasympathomimetic agents | Increase aqueous outflow | 20% to 30% | Three to four times daily/green cap | Miosis with refractive changes, burning, stinging, headache, cataracts | Rare cholinergic adverseeffects; increased salivation | Ocular inflammation Dicyclomine | Pilocarpine | $20 |

| Combination medications|| | — | — | — | — | — | — | Brinzolamide/brimonidine (Simbrinza) Latanoprost/netarsudil (Rocklatan) Timolol/brimonidine (Combigan) Timolol/dorzolamide (Cosopt; Cosopt PF) | – ($185) – ($320) $70 ($210) $2 ($200) |

The most used topical medications are prostaglandin analogues, beta blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, parasympathomimetic agents, and alpha agonists. Two newer medications for glaucoma are latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta) and netarsudil (Rhopressa). These newer medications work by different mechanisms and complement the actions of first-line glaucoma treatments.5,9,27 The medication can be switched or a combination therapy can be used if a single drug does not lower IOP satisfactorily.1–5,27

TREATMENT WITH PROCEDURES

Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) can also be used as a first-line treatment for POAG.28 SLT uses laser energy applied to the trabecular meshwork, reducing resistance to aqueous outflow. In the Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty Versus Eye Drops for First-Line Treatment of Ocular Hypertension and Glaucoma (LiGHT) trial, patients randomized to SLT had better outcomes than those randomized to topical medications, including less rapid visual field loss and fewer adverse effects from medication, and they did not have vision-threatening complications. SLT was more cost-effective, and patients had similar quality-of-life scores. The LiGHT trial demonstrated that 75% of patients required no other therapy over three years; however, ongoing monitoring is still necessary and additional treatments may be required.28

Incisional surgery (creating a small hole in the sclera to facilitate aqueous fluid drainage) or several minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries can be used when medication or SLT is insufficient to control disease progression. Cataract surgery can also be beneficial; however, it typically results in only a slight reduction in IOP.2,3,5,29–31

ROLE OF PRIMARY CARE PHYSICIANS

It is logical to consider screening for glaucoma in primary care because diagnosis and treatment of POAG in the asymptomatic stages can prevent vision loss. However, determining the presence of early glaucoma is challenging because findings of elevated IOP and changes in the optic cup do not accurately identify patients at risk of vision loss.5,23 Additionally, measuring IOP with tonometry, performing dilated funduscopic examinations, and formal testing of the visual field are not typically done in primary care settings.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) reaffirmed that evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for POAG in the general adult population because there are no demonstrated benefits of screening on vision-related quality of life or function.5,9 The underrepresentation of people in the United States of African descent (a population group at higher risk of glaucoma) in some studies may have affected these conclusions, and the USPSTF called for studies that target populations at higher risk.9,17 The USPSTF found that screening frail, older individuals was, for unclear reasons, associated with an increased risk of falls, but this is possibly related to difficulty adapting to lenses causing substantial corrections in vision.9

Despite the USPSTF recommendation, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services covers glaucoma screening examinations by eye care professionals for people at high risk due to diabetes, family history of glaucoma, African descent and age of 50 years or older, and Hispanic heritage with an age of 65 years or older.32 [corrected] The American Academy of Ophthalmology sponsors Eyecare America, which offers no-cost glaucoma examinations and follow-up care for eligible patients.33 For patients in rural or underserved areas where access to an eye specialist is limited, primary care physicians can consider tonometry screening in high-risk patients; however, such screening is not always accurate, is not recommended by the USPSTF, and may not be covered by insurance.

Primary care physicians should encourage adherence to treatment for patients diagnosed with POAG and receiving IOP medications. Studies show that adherence to glaucoma medications is generally poor; at best, 50% of patients use topical medications consistently over four years.3,34,35 Physicians should ask patients about barriers to taking their glaucoma medication and encourage the use of automated reminders.3,34,35 The most common causes of nonadherence are cost and adverse effects. Prescriptions for generic alternatives and a return to the eye specialist for definitive surgical treatment may help address long-term barriers to adherence.3,34,35

Primary care physicians should avoid medical treatments that can affect the course of glaucoma, such as treatment for nocturnal diastolic hypotension, which may hasten visual field loss. Aggressive blood pressure lowering should be avoided in patients at high risk of glaucoma-related vision loss.5 Corticosteroids can directly contribute to ocular hypertension; therefore, referring patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy to an eye care professional is recommended.3,5,36

Angle-Closure Glaucoma

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In ACG, aqueous outflow through the trabecular meshwork becomes blocked by the iris due to a narrow angle between the iris and the lens. When this blockage happens abruptly, such as from medication-induced iris dilation, it results in a sudden increase in IOP with distortion of vision. The abrupt blockage is an ophthalmologic emergency because it can acutely damage the optic nerve and result in blindness.2,3,8,37 This blockage can also occur chronically, such as from the deposition of infiltrates or neovascularization in the anterior chamber.38

RISK FACTORS

Hyperopia (i.e., farsightedness) increases risk and medications such as anticholinergics, adrenergics, and antidepressants can cause pupillary dilation and acute angle closure (Table 42,3,37). Sulfonamide antibiotics, diuretics, and topiramate are thought to precipitate angle closure via ciliary body edema.

| Adrenergic | Naphazoline intranasal Salbutamol inhaled |

| Anticholinergic | Oxybutynin Scopolamine |

| Antidepressants | Bupropion Escitalopram Fluoxetine Tricyclics Venlafaxine |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine Promethazine |

| Antiparkinsonians | Benztropine Trihexyphenidyl |

| Antipsychotics with anticholinergic properties | Olanzapine (Zyprexa) Quetiapine Thioridazine |

| Cocaine, methamphetamine | — |

| Histamine H2 blocker | Cimetidine |

| Mefenamic acid | — |

| Neurotoxin | OnabotulinumtoxinA |

| Sulfa drugs | Acetazolamide* Methazolamide* Topiramate Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Acute ACG typically presents with sudden blurred vision, unilateral eye pain, headache (often unilateral), and nausea.2,3,28 The patient’s history may identify a precipitating condition, such as activity in low light that results in marked pupillary dilation or the recent use of common medications causing pupillary dilation. There may also be a history of similar episodes of haloes and transient blurred vision that resolved spontaneously.

TREATMENT

In acute ACG, rapid reduction of IOP is essential to preventing further damage to the optic nerve. Although the ophthalmologist may attempt the use of topical, oral, and intravenous medications to lower the pressure acutely, definitive therapy typically involves a surgical intervention to clear the obstruction and promote aqueous drainage. These procedures include laser peripheral iridotomy, lens extraction, or anterior chamber paracentesis as appropriate to decrease IOP and prevent the loss of vision.2,3,35,41

| Treatment* | Purpose/comment |

|---|---|

| Intravenous acetazolamide, 500 mg | Blocks production of aqueous humor |

| Intravenous mannitol, 1 to 2 g per kg | Rapidly reduces volume of aqueous humor |

| Topical apraclonidine 1% (Iopidine), one drop | Blocks production of aqueous humor |

| Topical pilocarpine 1% to 2%, one drop, two doses 15 minutes apart | Increases outflow of aqueous humor; use once intraocular pressure is reduced to less than 40 mm Hg because it is not effective at higher doses due to ischemic paralysis of the iris; should not be used if topiramate use is the cause of acute angle closure |

| Topical timolol 0.5% (Timoptic), one drop | Blocks production of aqueous humor |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Gupta and Chen,26 Distelhorst and Hughes,7 and Lewis, et al.42

Data Sources: A search was completed in PubMed, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, POEMS, and Ovid database. Key words searched were glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma, and angle-closure glaucoma. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, systematic reviews, and case series. The studies evaluating race and ethnicity were largely systematic reviews and were included due to the high prevalence of disease in certain populations. Search dates: January, February, June, and July 2022; and November 2022.

Figure 3 provided by Lisa Rosenberg, MD, University Eye Specialists, Chicago, Ill.