Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(3):282-291

Patient information: See related handout on lung nodules, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Pulmonary nodules are often incidentally discovered on chest imaging or from dedicated lung cancer screening. Screening adults 50 to 80 years of age who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit smoking within the past 15 years with low-dose computed tomography is associated with a decrease in cancer-associated mortality. Once a nodule is detected, specific radiographic and clinical features can be used in validated risk stratification models to assess the probability of malignancy and guide management. Solid pulmonary nodules less than 6 mm warrant surveillance imaging in patients at high risk, and nodules between 6 and 8 mm should be reassessed within 12 months, with the recommended interval varying by the risk of malignancy and an allowance for patient-physician decision-making. A functional assessment with positron emission tomography/computed tomography, nonsurgical biopsy, and resection should be considered for solid nodules 8 mm or greater and a high risk of malignancy. Subsolid nodules have a higher risk of cancer and should be followed with surveillance imaging for longer. Direct physician-patient communication, clinical decision support within electronic health records, and guideline-based management algorithms included in radiology reports are associated with increased compliance with existing guidelines.

The incidental discovery of pulmonary nodules on imaging studies of the chest or through dedicated screening programs for the detection of lung cancer is common. It is estimated that 1.57 million nodules are detected incidentally every year, 5% of which are malignant.1 The incidence of pulmonary nodules in lung cancer screening programs has been reported at approximately 27%, with 1.1% of patients diagnosed with lung cancer.2 Guidelines have been published to aid physicians in managing these nodules.3–5 Examples of benign causes of pulmonary nodules are listed in Table 1.6 All patients with a pulmonary nodule and a history of malignancy, with multiple nodules but no dominant nodule, with any pulmonary mass (i.e., lung opacity of greater than 3 cm in diameter), or who are immunocompromised should be referred to a pulmonologist for further workup.7

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Benign tumor | Chondroma Hamartoma Lipoma |

| Congenital | Arteriovenous malformation Bronchogenic cyst |

| Immune-mediated disease | Rheumatoid arthritis Sarcoidosis |

| Infectious | Infectious granuloma* Coccidioidomycosis Histoplasmosis Mycobacterium tuberculosis Lung abscess |

| Other | Amyloidosis Endoparenchymal lymph node |

What Nodule and Patient Characteristics Suggest a Malignant Cause?

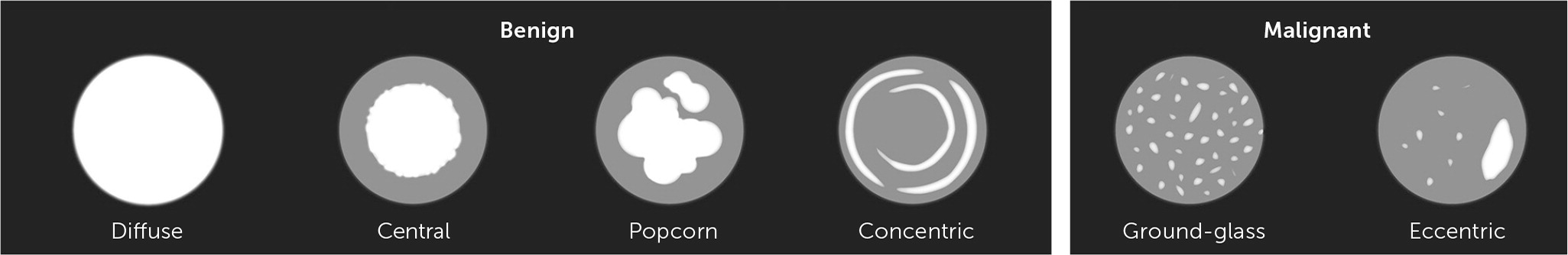

The risk of malignancy is higher in solid nodules that are large, have irregular borders, have asymmetric calcifications, have a volume doubling time between one month and one year, or are in the upper lung lobes. Subsolid nodules are more likely to be cancerous than solid nodules. Increasing age and history of cigarette smoking are associated with a higher risk of lung cancer.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Malignancy is more common in solid nodules that are 6 mm or greater in diameter.3 Other nodule characteristics associated with cancer include location in the upper lung lobes, irregular or spiculated borders, ground-glass appearance, or punctate or eccentric calcifications7 (Figure 18). Nodules with a volume doubling time of more than 30 days to less than 400 days are also associated with malignancy because nodules that grow rapidly over days to weeks are more likely to be infectious or inflammatory, and aggressive cancers can double in volume every three to four months (Table 2).7 Significant growth found on follow-up imaging is presumptive evidence of malignancy and requires consultation with a pulmonary subspecialist or more frequent monitoring. Subsolid nodules include pure ground-glass and part-solid nodules. Although less common than solid nodules (21% vs. 79% in one lung cancer screening study), part-solid nodules are associated with a higher risk of slow-growing cancer.9 Increasing age, greater than 20-pack-year smoking history among current smokers or those who have quit within the past 15 years, a family history of lung cancer, and exposure to asbestos, uranium, or radium are associated with an increased risk of pulmonary malignancy.3

| Feature | Suggests benign etiology | Suggests malignant etiology |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Concentric, central, diffuse, or popcorn-like calcifications | Eccentric calcifications, noncalcified, or ground-glass |

| Border | Smooth | Spiculated (higher risk) or irregular |

| Density | Solid | Subsolid |

| Location | Perifissural, subpleural | Upper lobes |

| Multiple nodules | Dominant nodule present | No dominant nodule present |

| Size | < 6 mm | ≥ 6 mm |

| Volume doubling time | Less than 30 days or greater than 400 days | Between 30 and 400 days |

What Is the Evidence for Screening Asymptomatic People for Lung Cancer?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (CT) in adults 50 to 80 years of age who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or quit smoking within the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or a willingness to have curative lung surgery (USPSTF Grade B recommendation).10

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The National Lung Screening Trial compared annual low-dose CT to chest radiography for three consecutive years in patients at high risk (defined as 55 to 74 years of age with at least a 30-pack-year smoking history who were current smokers or had quit within the previous 15 years). After 6.5 years of follow-up, there was a 20% reduction in lung cancer–related mortality and a 6.7% decrease in overall mortality in the low-dose CT group.11 A more recent meta-analysis of more than 96,000 people that included the National Lung Screening Trial data demonstrated that screening people at high risk with low-dose CT decreased lung cancer–related mortality by 1.8% to 2.2% over five to 10 years but did not change overall mortality.12 In 2014, the USPSTF recommended the use of low-dose CT for lung cancer screening in people at high risk13; this recommendation was updated in 2021 based on data from additional studies and screening models showing benefits for a larger age range (50 to 80 years of age) and shorter smoking history (20-pack-year smoking history) and is endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians.10,14 Screening patients at high risk of lung cancer with low-dose CT is also recommended by the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) and the American Cancer Society, with screening starting at 55 years of age for patients with a 30-pack-year smoking history who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.15,16

What Is the Recommended Management of a Nodule Identified During Lung Cancer Screening?

Repeat low-dose CT is recommended for benign or probably benign nodules; the screening interval depends on the morphology and size of the initial lesion. Additional imaging or referral for biopsy should be considered for patients with very suspicious large solid nodules (15 mm and greater or 8 mm and greater that are new or growing) and subsolid nodules with large solid components (8 mm or greater or 4 mm and greater that are new or growing).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The American College of Radiology Lung-RADS score provides management recommendations for pulmonary nodules found during lung cancer screening and is recommended by pulmonary societies3,5,15 (Table 35). Patients with a negative screening result or benign-appearing nodules should continue routine annual low-dose CT screening. Probably benign lesions should be reimaged with low-dose CT in six months. Suspicious lesions should be reimaged with low-dose CT in three months.

| Category descriptor | Lung-RADS | Findings | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Estimated population prevalence: ~ 1% | 0 | Prior chest CT examination being located for comparison (see note 9) Part or all of lungs cannot be evaluated Findings suggestive of an inflammatory or infectious process (see note 10) | Comparison to prior chest CT Additional lung cancer screening CT imaging needed 1- to 3-month LDCT |

| Negative Estimated population prevalence: 39% | 1 | No lung nodules OR Nodule with benign features: complete, central, popcorn, or concentric calcifications OR fat-containing | 12-month screening LDCT |

| Benign Based on imaging features or indolent behavior Estimated population prevalence: 45% | 2 | Juxtapleural nodule: < 10 mm mean diameter at baseline or new AND solid, smooth margins; and oval, lentiform, or triangular shape Solid nodule: < 6 mm at baseline OR new < 4 mm Part-solid nodule: < 6 mm total mean diameter at baseline Nonsolid nodule (ground-glass nodule): < 30 mm at baseline, new or growing OR ≥ 30 mm stable or slow-growing (see note 7) Airway nodule, subsegmental at baseline, new, or stable (see note 11) Category 3 nodule that is stable or decreased in size at 6-month follow-up CT, OR category 3 or 4A nodules that resolve on follow-up, OR category 4B findings proven to be benign in etiology following appropriate diagnostic workup | 12-month screening LDCT |

| Probably benign Based on imaging features or behavior Estimated population prevalence: 9% | 3 | Solid nodule: ≥ 6 to < 8 mm at baseline OR new 4 to < 6 mm Part-solid nodule: ≥ 6 mm total mean diameter with solid component < 6 mm at baseline OR new < 6 mm in total mean diameter Nonsolid nodule (ground-glass nodule): ≥ 30 mm at baseline or new Atypical pulmonary cyst: (see note 12) growing cystic component (mean diameter) of a thick-walled cyst Category 4A nodule that is stable or decreased in size at 3-month follow-up CT (excluding airway nodules) | 6-month LDCT |

| Suspicious Estimated population prevalence: 4% | 4A | Solid nodule: ≥ 8 to < 15 mm at baseline OR growing < 8 mm OR new 6 to < 8 mm Part-solid nodule: ≥ 6 mm with solid component ≥ 6 to < 8 mm at baseline OR new or growing < 4 mm solid component Airway nodule, segmental or more proximal at baseline or new (see note 11) Atypical pulmonary cyst: (see note 12) thick-walled cyst OR multilocular cyst at baseline OR thin- or thick-walled cyst that becomes multilocular | 3-month LDCT; PET/CT may be considered if there is a ≥ 8 mm solid nodule or solid component |

| Very suspicious Estimated population prevalence 2% | 4B | Airway nodule, segmental or more proximal, and stable or growing (see note 11) Solid nodule: ≥ 15 mm at baseline OR new or growing ≥ 8 mm Part-solid nodule: solid component ≥ 8 mm at baseline OR new or growing ≥ 4 mm solid component Atypical pulmonary cyst: (see note 12) thick-walled cyst with growing wall thickness/nodularity OR growing multilocular cyst (mean diameter) OR multilocular cyst with increased loculation or new/increased/opacity (nodular, ground glass, or consolidation) Slow-growing solid or part-solid nodule that demonstrates growth over multiple screening exams (see note 8) | Referral for further clinical evaluation Diagnostic chest CT with or without contrast; PET/CT may be considered if there is a ≥ 8 mm solid nodule or solid component; tissue sampling; and/or referral for further clinical evaluation Management depends on evaluation, patient preference, and the probability of malignancy (see note 13) |

| Estimated population prevalence < 1% | 4X | Category 3 or 4 nodules with additional features or imaging findings that increase suspicion for lung cancer (see note 14)w | |

| Significant or potentially significant Estimated population prevalence 10% | S | Modifier: may add to category 0–4 for clinically significant or potentially clinically significant findings unrelated to lung cancer (see note 15) | As appropriate to the specific finding |

Positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) imaging is used to assess the metabolic activity of a nodule. Although malignant nodules may be more metabolically active, some inflammatory and infectious nodules also may have high uptake on PET/CT7; the reported sensitivity is 89% and specificity is 75% for detecting lung cancer.17 The Lung-RADS guidelines state that PET/CT may be used in evaluating suspicious or very suspicious lesions with a solid component of 8 mm or greater.5 Physicians should be mindful of the cumulative dose of radiation to which a patient is exposed in screening and follow-up studies, which ranges from low-dose CT (1.5 mSv), to CT of the chest (6.1 mSv), to full-body PET/CT (22.7 mSv).18

Referral to pulmonology, interventional radiology, or thoracic surgery for lung biopsy should be considered for solid nodules 15 mm or greater or new or growing nodules 8 mm or greater. Referral should also be considered for subsolid nodules if the solid component is 8 mm or greater or 4 mm or greater and is new or growing. The presence of additional features of malignancy, such as spiculation, doubling of nodule size in one year, or lymphadenopathy, may also indicate a nodule that requires biopsy.5 Lung-RADS scoring may decrease the number of subsequent unnecessary diagnostic procedures when used as part of a lung cancer screening program.19

What Tools Help Physicians Risk Stratify Incidentally Discovered Pulmonary Nodules?

Validated risk calculators estimate the chance of malignancy for incidentally discovered pulmonary nodules. All calculators use history and nodule characteristics found on low-dose CT; some calculators use the results of PET/CT.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Although many incidentally discovered lung nodules are found on CT, nodules may also be found on plain radiography. CHEST recommends that unless nodules can be clearly classified as benign (e.g., due to a benign pattern of calcification), chest CT with thin sections is recommended due to its better sensitivity and specificity for detecting lung malignancy compared with plain radiography, and its ability to provide additional information such as size and attenuation characteristics of any lesions.4

Guidelines from the Fleischner Society and CHEST recommend using malignancy risk prediction models for patients with incidentally discovered pulmonary nodules to help determine management.3,4 Individual patient risk of malignancy can be classified as high risk (greater than 65%), intermediate risk (5% to 65%), and low risk (less than 5%).4 Validated risk prediction models have been developed and have online tools to help with their implementation into practice (Table 420–24). Physicians should choose a calculator that best represents the characteristics of the patient being assessed.7 Note that although the accuracy of these tools has been established, their clinical usefulness has not been verified and may not add much beyond the clinical expertise and interpretation provided by specialists or radiologists.7

| Characteristic | Mayo Clinic | U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs | Herder | Cleveland Clinic | PanCan (Brock University) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristic | Incidental nodule on chest radiography | Incidental nodule on chest radiography confirmed with CT | Incidental nodule on chest radiography with PET/CT performed | Incidental nodules referred for biopsy or lung resection | Nodules detected during lung cancer screening |

| Components of model | Age Extrathoracic cancer ≥ 5 years ago Nodule diameter Smoking history Spiculation Upper lobe location | Age Nodule diameter Smoking history Time since quitting smoking | Age Extrathoracic cancer ≥ 5 years ago PET/CT results Nodule diameter Smoking history Spiculation Upper lobe location | Age Presence of emphysema PET/CT results History of nonlung cancer Smoking history Solid and irregular edges Upper lobe location | Age Presence of emphysema Family history of lung cancer Location Nodule count Nodule size Nodule type Patient sex |

| Website | https://reference.medscape.com/calculator/solitary-pulmonary-nodule-risk | Available in original article23: https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(15)48320-5/fulltext | http://www.nucmed.com/nucmed/spn_risk_calculator.aspx | Available in original article24: https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(19)30689-0/fulltext | https://www.uptodate.com/contents/calculator-solitary-pulmonary-nodule-malignancy-risk-in-adults-brock-university-cancer-prediction-equation |

What Is the Recommended Management of an Incidentally Detected Solid Pulmonary Nodule?

The Fleischner Society and CHEST recommend no follow-up for small, low-risk nodules and scheduled follow-up with CT for medium-sized nodules. The Fleischner Society recommends short-term CT follow-up, PET/CT, or tissue sampling for large nodules, whereas CHEST recommends management based on the risk of malignancy.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Management of solid pulmonary nodules varies among guidelines (Table 5).3,4 The Fleischner Society recommends follow-up be performed based on nodule size (less than 6 mm, 6 to 8 mm, greater than 8 mm) and risk assessment (high, which combines the intermediate- and high-risk groups; or low).3 High-risk factors include older age, significant smoking history, larger nodule size, irregular or spiculated borders, or upper lobe location. Low-risk factors include young age, less smoking, smaller nodule size, regular margins, and location not in the upper lobes. Patients at low risk with small nodules (less than 6 mm) do not require further surveillance. Repeat CT at 12 months may be considered in patients at high risk. Short-interval imaging with CT in six to 12 months is recommended for medium-sized nodules (6 to 8 mm) regardless of the risk category, followed by more frequent surveillance. For large nodules (greater than 8 mm), physicians should consider CT in three months, PET/CT, or referral for tissue sampling.

| Nodule size* | Assigned risk† | American College of Chest Physicians | Fleischner Society |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (< 6 mm) | High risk Low risk | ≤ 4 mm: CT at 12 months (if stable, no further follow-up) > 4 to 6 mm: CT at six to 12 months (if stable, repeat CT at 18 to 24 months) ≤ 4 mm: patient discussion, with option for follow-up > 4 to 6 mm: follow-up CT at 12 months (if stable, no further follow-up) | Optional: follow-up CT in 12 months No follow-up |

| Medium (6 to 8 mm) | High risk Low risk | CT at three to six months (if stable, then nine to 12 months and 24 months) CT at six to 12 months (if stable, follow-up at 18 to 24 months) | CT in six to 12 months, then repeat CT in 18 to 24 months CT in six to 12 months, then consider repeat CT at 18 to 24 months |

| Large (> 8 mm) | High/low risk | ≥ 8 mm: calculate probability of malignancy: Pretest probability < 5%: surveillance CT in three months Pretest probability 5% to 65%: PET/CT with plan for continued surveillance, nonsurgical biopsy, or surgical biopsy/resection Pretest probability > 65%: surgical biopsy or resection after staging | Consider follow-up CT at three months, PET/CT, or tissue sampling |

The CHEST guideline makes similar recommendations for small and medium-sized nodules.4 However, for large nodules, management differs based on the risk of malignancy, which includes the use of risk prediction models. Patients at low risk (less than 5%) may be followed with low-dose CT in three months. Patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (5% to 65%) may be offered PET/CT to define the risk of malignancy further or determine the need for a biopsy. Peripherally located nodules are often more accessible by CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsies, whereas bronchoscopy may more easily reach nodules nearer to an airway.7 In one meta-analysis, transthoracic needle biopsies had a higher diagnostic yield than bronchoscopy (93% vs. 75%) but were also associated with a higher risk of bleeding and pneumothorax.25 Technological advances in bronchoscopy have improved diagnostic yield with similarly low complication rates.26

When the risk of malignancy is high (greater than 65%), surgical resection is recommended for patients who can tolerate the procedure.7 Nonsurgical options, including biopsy, stereotactic radiotherapy, or ablative therapies, may be considered for patients at very high risk of death from the resection procedure.

What Is the Recommended Management for Incidentally Detected Subsolid Nodules?

Small subsolid nodules (5 mm or less per CHEST, less than 6 mm per the Fleischner Society) do not require further imaging. Regular surveillance imaging with CT is recommended for intermediate-sized (6 to 8 mm) subsolid nodules, and larger (greater than 8 mm) subsolid nodules are managed similarly to large solid nodules.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

CHEST and Fleischner Society guidelines do not recommend further imaging for small subsolid pulmonary nodules. Larger ground-glass nodules should be followed with repeat CT at six to 12 months, then periodically for the next few years (Table 6).3,4 CHEST recommends that part-solid, 6 to 8 mm nodules be reimaged with CT at three, 12, and 24 months, then annually for five years. Nodules greater than 8 mm should have follow-up CT at three months with PET/CT, biopsy, or resection if the nodule persists. The Fleischner Society recommends repeat CT in three to six months for part-solid nodules 6 mm or greater, then annually for five years.

| Nodule size | American College of Chest Physicians | Fleischner Society |

|---|---|---|

| Small | ≤ 5 mm: no follow-up | < 6 mm: no routine follow-up for ground-glass or part-solid nodules |

| Large | > 5 mm Ground-glass: CT at 12 months, then annual CT for three years Part-solid nodule: ≤ 8 mm solid component: CT at three, 12, and 24 months, then annually for five years > 8 mm solid component: CT at three months, further evaluation with PET/CT, biopsy, or resection if nodule persists | ≥ 6 mm Ground-glass: CT at six to 12 months, then every two to five years Subsolid nodule: CT at three to six months, then annually for five years |

What Factors Are Associated With Improved Adherence to These Guidelines?

Adherence to guidelines is improved with high-quality physician-patient communication, clinical decision support tools, and radiology reports that include guideline templates.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In one study, only 55% of patients with pulmonary nodules of any type diagnosed outside of a lung cancer screening program received appropriate, guideline-based care.27 Direct physician-patient communication, clinical decision support within electronic health records, and guideline-based management algorithms included in radiology reports are all associated with increased compliance with guidelines.28–30 Conversely, inappropriate or incomplete radiology reports, receiving care at multiple facilities, and incidental detection during inpatient care or preoperative visits are associated with subsequent nonadherence to published guidelines.27

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Kikano, et al.,8 and Albert and Russell.31

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms solitary pulmonary nodule, diagnosis, management, and lung cancer screening. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Search dates: March 4, 2022 to July 15, 2022, August 20, 2022, and January 23, 2023.