This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(4):415-420

Patient information: See related handout on Bell palsy.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Bell palsy should be suspected in patients with acute onset of unilateral facial weakness or paralysis involving the forehead in the absence of other neurologic abnormalities. The overall prognosis is good. More than two-thirds of patients with typical Bell palsy have a complete spontaneous recovery. For children and pregnant women, the rate of complete recovery is up to 90%. Bell palsy is idiopathic. Laboratory testing and imaging are not required for diagnosis. When other causes of facial weakness are being considered, laboratory testing may identify a treatable cause. An oral corticosteroid regimen (prednisone, 50 to 60 mg per day for five days followed by a five-day taper) is the first-line treatment for Bell palsy. Combination therapy with an oral corticosteroid and antiviral may reduce rates of synkinesis (misdirected regrowth of facial nerve fibers manifesting as involuntary co-contraction of certain facial muscles). Recommended antivirals include valacyclovir (1 g three times per day for seven days) or acyclovir (400 mg five times per day for 10 days). Treatment with antivirals alone is ineffective and not recommended. Physical therapy may be beneficial in patients with more severe paralysis.

Bell palsy is acute facial paralysis or weakness caused by peripheral cranial nerve VII (facial) dysfunction of unknown etiology. This article provides a brief overview of patient-oriented evidence for the primary care of patients with Bell palsy.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with Bell palsy should be prescribed oral corticosteroids.3,17,18 | A | Meta-analysis with high degree of certainty |

| Combination therapy with oral corticosteroids and antivirals should be considered in patients with Bell palsy to reduce rates of synkinesis.5,17,18,22 | B | Meta-analysis with moderate degree of certainty |

| Patients with Bell palsy should not be treated with antivirals alone.5,17,22 | A | Meta-analysis with high degree of certainty |

| Physical therapy should be offered to patients with severe paralysis (House-Brackmann grade V or VI) or persistent paralysis (more than three months).28,29 | B | Cochrane review of lower-quality studies; one high-quality randomized trial |

Epidemiology

The estimated incidence of Bell palsy is 20 to 30 cases per 100,000 people per year.1–4

All ages can be affected, with the highest incidence in people 15 to 45 years of age.1–4

An equal number of left-sided and right-sided cases are reported.3,5

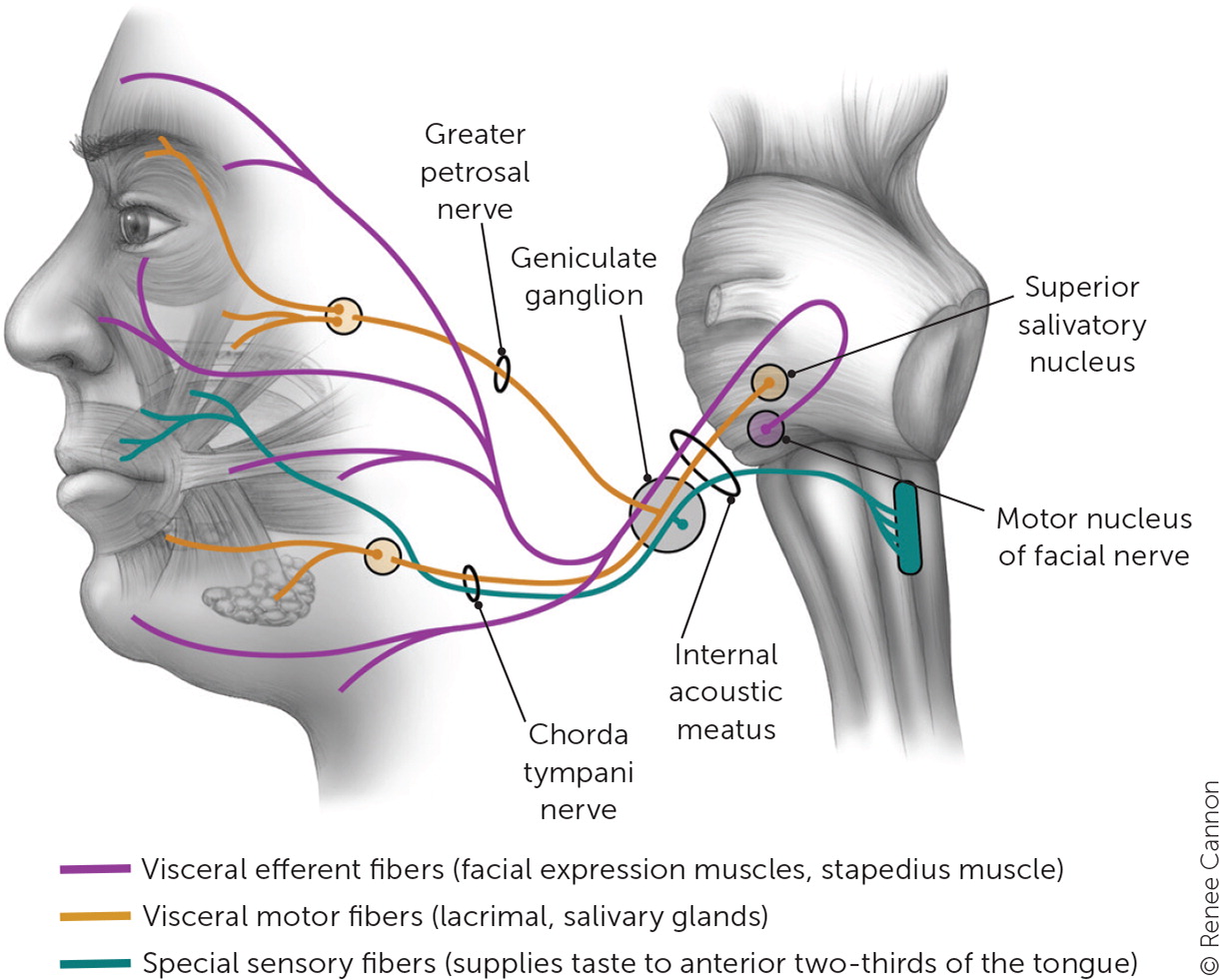

Bell palsy is associated with nerve edema and mechanical compression of cranial nerve VII.6 The anatomy of this nerve is illustrated in Figure 1.7

Based on epidemiologic studies, risk factors include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, immunosuppression, influenza A and other upper respiratory illnesses, and pregnancy.1,2,3,5,8,9

Diagnosis

Bell palsy should be suspected in patients with acute onset of unilateral facial weakness or paralysis involving the forehead in the absence of other neurologic abnormalities.4

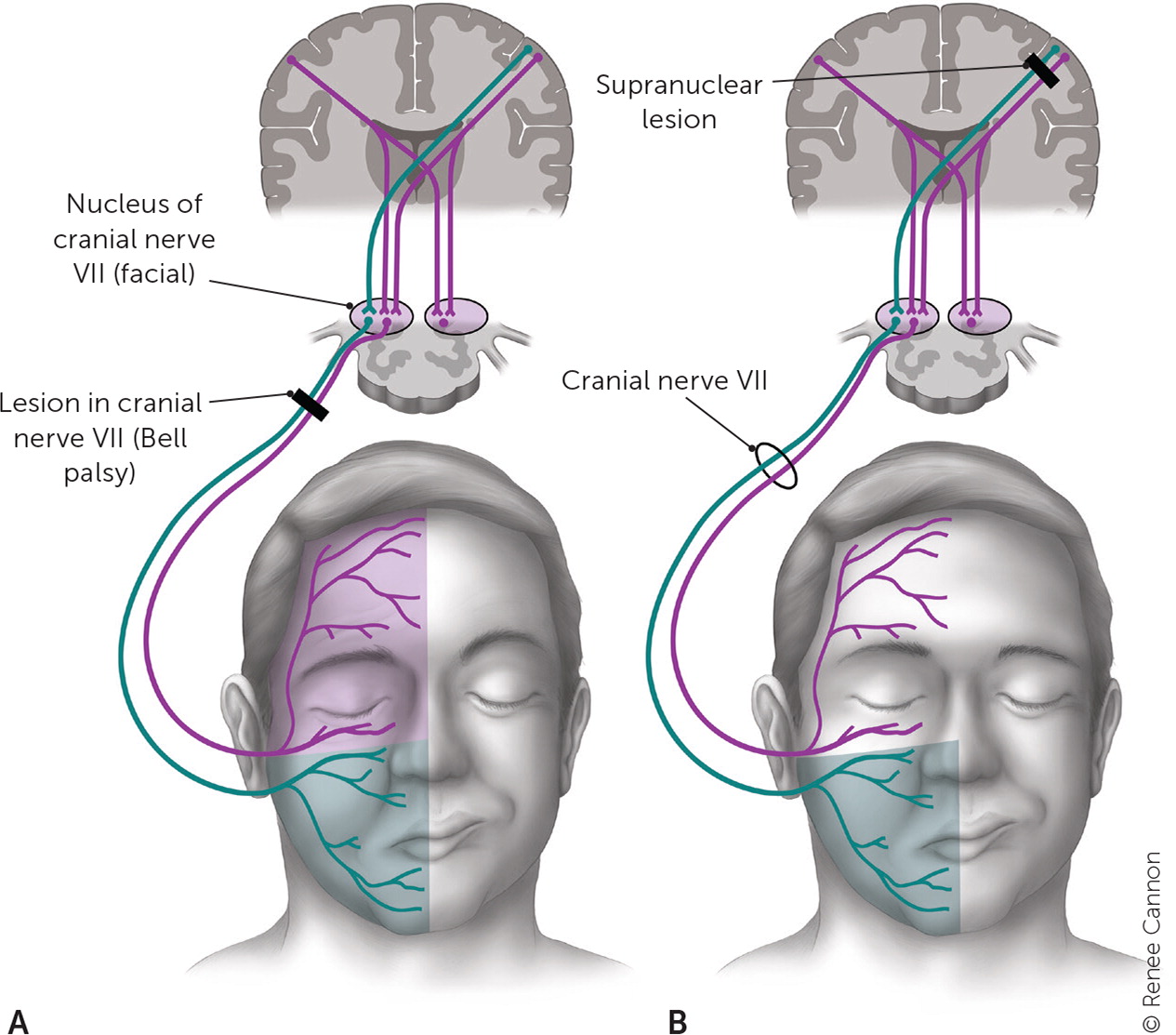

Alternative diagnoses should be considered in patients with bilateral involvement, sparing of the forehead, abnormal extraocular movements, hearing loss, tinnitus, or vertigo. These findings indicate an upper motor neuron lesion or a lesion involving more than just cranial nerve VII10 (Figure 27).

Other diagnoses should be considered in patients with gradual onset of symptoms, prolonged course (more than three months without improvement), limb or bulbar weakness, systemic or localized facial skin cancer, signs of infection, or risk of infection.11

Additional evaluation should be considered in patients with ipsilateral recurrent Bell palsy because this could suggest an underlying tumor.12

The differential diagnosis of Bell palsy includes structural lesions, infection, autoimmune conditions, stroke, and multiple sclerosis (Table 1).7

| Diagnosis | Cause | Distinguishing factors |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | ||

| Lyme disease | Spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi | History of tick exposure, rash, or arthralgias; residing in or travel to endemic regions; bilateral facial weakness |

| Otitis media | Bacterial pathogens | Gradual onset; ear pain, fever, conductive hearing loss |

| Viral infections | COVID-19, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex, HIV, influenza A, mumps, rubella, other viruses | Coryza; symptoms of specific viral infections |

| Ramsay Hunt syndrome | Herpes zoster virus | Pronounced prodromal pain; vesicular eruption in ear canal or pharynx |

| Sarcoidosis, myasthenia gravis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome | Autoimmune response | More often bilateral |

| Tumor | Cholesteatoma, parotid gland tumor | Gradual onset |

| Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome | Genetic condition | Onset in childhood or early adolescence; associated facial swelling, fissured tongue |

| Iatrogenic | Botulinum toxin injection | Weakness at injection site |

| Central (forehead spared) | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | Demyelination | Other neurologic symptoms |

| Stroke | Ischemia, hemorrhage | Extremities on affected side often involved; other neurologic symptoms (e.g., aphasia, unilateral neglect, sensory loss) |

| Tumor | Metastases, primary brain tumor | Gradual onset; mental status changes, history of cancer |

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Bell palsy presents as mouth droop, flattening of the nasolabial fold, inability to close the eye, and smoothing of the brow on one side of the face.13

Symptoms of Bell palsy are rarely bilateral.14

Symptoms typically develop acutely (over one to three days), peak within the first week, and gradually resolve over weeks to months.

Patients with Bell palsy experience a spectrum of symptom severity. The Sunnybrook scale and House-Brackmann scale are commonly used to classify symptom severity.

House-Brackmann scale15 [corrected]:

○ Grade I, normal: normal facial function in all areas.

○ Grade II, slight symptoms: slight weakness on close inspection, slight synkinesis, complete eyelid closure with minimal effort.

○ Grade III, moderate symptoms: Obvious but not disfiguring facial asymmetry, synkinesis is noticeable but not severe, may have hemifacial spasm or contracture, complete eyelid closure with effort, mouth is slightly weak with maximal effort.

○ Grade IV, moderately severe symptoms: Disfiguring facial asymmetry or obvious facial weakness, forehead cannot move, incomplete eyelid closure, mouth is asymmetrical with maximal effort.

○ Grade V, severe symptoms: only slight, barely noticeable facial movement, asymmetric facial appearance, forehead cannot move, incomplete eyelid closure, mouth has only slight movement.

○ Grade VI, total paralysis: no facial movement.

Physical examination maneuvers to demonstrate the degree and extent of facial weakness include having patients raise their eyebrows, close their eyes, frown, show their teeth, and pucker their lips.

Patients who can close their eyes tightly and wrinkle their forehead on the affected side should be evaluated for a central lesion.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Laboratory tests and radiography are not needed to diagnose Bell palsy.

Laboratory tests can identify systemic causes of peripheral facial palsy such as diabetes and Lyme disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the head or orbits/face/neck, with and without intravenous contrast, is recommended in patients with recurrent Bell palsy.16

Treatment

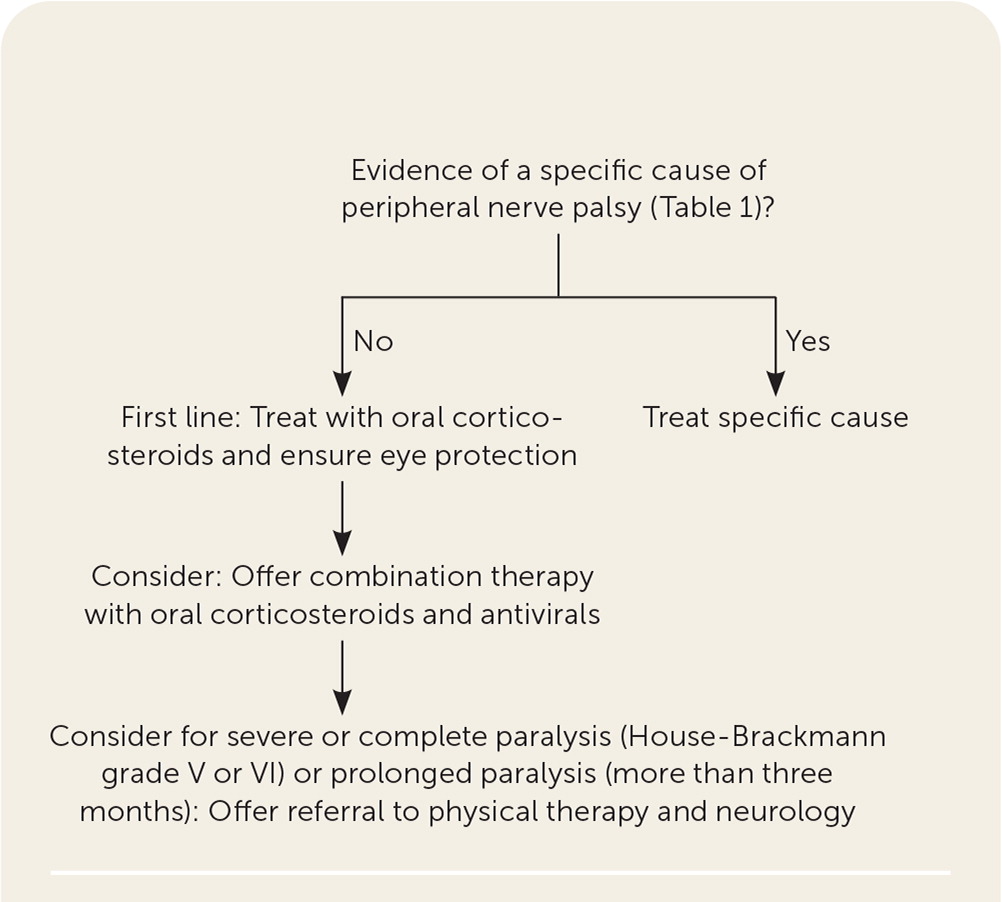

Figure 3 presents a suggested app roach to the treatment of Bell palsy.

MEDICAL THERAPY

Patients with Bell palsy should be treated with oral corticosteroids, which have been shown to improve rates of full recovery (number needed to treat = 10) and reduce rates of synkinesis in adults.3,17,18 Typical prednisone doses reported in trials range from 50 to 60 mg per day for five days followed by a five-day taper.3,17

A meta-analysis compared rates of unsatisfactory recovery for a cumulative corticosteroid dose of less than 450 mg vs. 450 mg or more. Unsatisfactory recovery was more likely with the lower dose range compared with the higher range (30% vs. 14%).17

Patients with Bell palsy should be offered combination therapy with oral corticosteroids and antivirals.5,19–21 Combination therapy consistently leads to lower rates of synkinesis (number needed to treat = 12).5,17,18,22

The effectiveness of combination therapy for improving rates of complete recovery in patients with Bell palsy is unclear.

○ Two meta-analyses of higher-quality trials showed that combination therapy does not increase rates of complete recovery.5,22

○ Meta-analyses and a network meta-analysis of heterogeneous low-quality trials showed that combination therapy may reduce rates of incomplete recovery without an increase in adverse events.5,18,22

○ Regimens of antiviral therapy reported in trials included valacyclovir, 1 g three times per day for seven days, and acyclovir, 400 mg five times per day for 10 days. Treatment outcomes were similar regardless of disease severity.5,22

○ Oral antivirals are well tolerated.5 There are no compelling effectiveness data to recommend one antiviral over another.23

Although there is limited evidence showing that corticosteroids are beneficial in pregnant patients with Bell palsy, consensus practice is to treat these patients similarly to non-pregnant adults, with corticosteroids early in the disease course.9,24

A study that randomized 187 children to treatment with prednisolone or placebo within three days of symptom onset found no difference in rates of complete recovery of facial function at one, three, and six months.6,25

Patients with Bell palsy should not be treated with antivirals alone. There is strong evidence that antivirals alone have no effect on recovery.5,17,22

SURGICAL TREATMENT

EYE CARE

PHYSICAL THERAPY

Facial physical therapy should be offered to patients with severe or complete paralysis (House-Brackmann grade V or VI) or prolonged paralysis (more than three months), based on a Cochrane review of lower-quality studies and on one high-quality randomized trial.28,29 It is unclear whether electrostimulation is effective, and there is evidence that it may worsen outcomes.28,30,31

There is no high-quality evidence showing that treatment with low-level or high-level laser therapy, hyperbaric oxygen, intratympanic steroid injections, or stellate ganglion blocks is more effective than standard medical therapy.32–35

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

Prognosis

Between 66% and 85% of patients who have Bell palsy will experience complete spontaneous recovery within three weeks, and this rate increases within eight weeks.29–39

Up to 90% of children younger than 14 years and pregnant patients will experience complete spontaneous recovery.6,9

Patients with bilateral disease or more severe peak symptoms (determined by the Sunnybrook or House-Brackmann scale) are less likely to experience full recovery.9

The recurrence rate of Bell palsy has been reported as 6.5%, with a mean interval of 10 years. Of patients with recurrence, 66% experience complete recovery.12

Synkinesis is a result of misdirected nerve regrowth and manifests as unintended ipsilateral co-contractions of muscles innervated by cranial nerve VII (e.g., contraction of the ipsilateral orbicularis oculi muscle [blinking] when smiling or when tearing with salivation [crocodile tears]). Synkinesis affects 26% of patients one year after onset of Bell palsy.3

Long-term sequelae of Bell palsy, especially the impairment of smiling, may lead to severe anxiety, depression, and other psychological problems.40

Neurology referral should be considered in patients with prolonged, bilateral, or recurrent symptoms.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Tiemstra and Khatkhate,7 and Albers and Tamang.41

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the key terms Bell’s palsy, Bell palsy, facial nerve palsy for human studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published after January 1, 2012. Reference lists from key articles were reviewed for additional sources. Essential Evidence Plus was also reviewed. Search dates: March and April 2022, January 12, 2023.