Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(4):358-368

Related editorial: Recent Changes in International Asthma Guidelines May Be Influenced by Pharmaceutical Industry Conflicts of Interest

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Asthma affects more than 25 million people in the United States, and 62% of adults with asthma do not have adequately controlled symptoms. Asthma severity and level of control should be assessed at diagnosis and evaluated at subsequent visits using validated tools such as the Asthma Control Test or the asthma APGAR (activities, persistent, triggers, asthma medications, response to therapy) tools. Short-acting beta2 agonists are preferred asthma reliever medications. Controller medications consist of inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta2 agonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonists, and leukotriene receptor antagonists. Treatment typically begins with inhaled corticosteroids, and additional medications or dosage increases should be added in a stepwise fashion according to guideline-directed therapy recommendations from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program or the Global Initiative for Asthma when symptoms are inadequately controlled. Single maintenance and reliever therapy combines an inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta2 agonist for controller and reliever treatments. This therapy is preferred for adults and adolescents because of its effectiveness in reducing severe exacerbations. Subcutaneous immunotherapy may be considered for those five years and older with mild to moderate allergic asthma; however, sublingual immunotherapy is not recommended. Patients with severe uncontrolled asthma despite appropriate treatment should be reassessed and considered for specialty referral. Biologic agents may be considered for patients with severe allergic and eosinophilic asthma.

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases in primary care. It affects more than 25 million people in the United States with a prevalence of 7.8% among adults and children.1 The range of evidence-based treatments has become better defined, although nuances and differences between guidelines exist. This article reviews common questions about outpatient asthma treatment and provides evidence-based answers.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not diagnose or manage asthma without spirometry. | American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology |

| Do not use long-acting beta2 agonist/corticosteroid combination drugs as initial therapy for intermittent or mild persistent asthma in children. | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| Avoid stepping up asthma therapy (i.e., adding new drugs or going to higher doses) before assessing adherence, appropriateness of device, and technique with current asthma medications. | American Academy of Pediatrics |

How Should Clinicians Assess Asthma Severity to Guide a Stepwise Approach to Treatment?

Asthma severity and control should be assessed at diagnosis and at subsequent visits by analyzing the level of impairment and the risk of future exacerbations. Once a diagnosis and treatment plan has been made, several validated tools may be used to assess control, including the Asthma Control Test and the asthma APGAR (activities, persistent, triggers, asthma medications, response to therapy) tools. Spirometry should be performed in all patients at diagnosis. There is weak evidence for repeating spirometry in patients with worsening symptom control.2,3 Evidence is limited for the use of adjuncts such as fractional excretion of nitric oxide and sputum eosinophils.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The regular assessment of asthma control is crucial because 62% of adults with the disease do not have adequately controlled asthma.4 The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) Expert Panel Report recommends classifying asthma severity based on reported symptoms at diagnosis to determine initial therapy (Table 1).2 The degree of control should be assessed using decision support tools such as the Asthma Control Test or the asthma APGAR.5 The Asthma Control Test is a validated questionnaire consisting of five to seven items with a sensitivity and specificity of 70% when using a cutoff value greater than 19 to classify patients as having well-controlled asthma. The questionnaire can be found at https://www.asthmacontroltest.com/welcome/. The asthma APGAR tools perform similarly to the Asthma Control Test and are available from the American Academy of Family Physicians at https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/nrn/nrn19-asthma-apgar.pdf. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated improved asthma control, fewer hospital admissions, and increased adherence to treatment guidelines; however, this finding may have limited generalizability, especially to patients attending inner-city clinics.6

| Patients not currently receiving long-term control medication* | |||||

| Components of severity | Classification of asthma severity | ||||

| Intermittent | Persistent | ||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Impairment Normal FEV1/FVC: 8 to 19 years = 85% 20 to 39 years = 80% 40 to 59 years = 75% 60 to 80 years = 70% | Symptoms | ≤ 2 days per week | > 2 days per week but not daily | Daily | Throughout the day |

| Nighttime awakenings | ≤ 2 times per month | 3 to 4 times per month | > 1 time per week but not nightly | Every night | |

| Short-acting beta2 agonist use for symptom control (not prevention of EIB) | ≤ 2 days per week | > 2 days per week but not > 1 time per day | Daily | Several times per day | |

| Interface with normal activity | None | Minor limitation | Some limitation | Extremely limited | |

| Lung function | Normal FEV1 between exacerbations FEV1 > 80% of predicted FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1 ≥ 80% of predicted FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1 > 60% but < 80% of predicted FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1 < 60% of predicted FEV1/FVC reduced > 5% | |

| Risk | Exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids | 0 to 1 per year† | ≥ 2 per year† | ≥ 2 per year† | ≥ 2 per year† |

| Consider severity and interval since last exacerbation; frequency and severity may fluctuate over time for patients in any severity category | |||||

| Relative annual risk of exacerbations may be related to FEV1 | |||||

| Patients after asthma becomes well controlled, by lowest level of treatment required to maintain control‡ | |||||

| Classification of asthma severity | |||||

| Intermittent | Persistent | ||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Lowest level of treatment required to maintain control (see Figure 1 for treatment steps) | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 or 4 | Step 5 or 6 | |

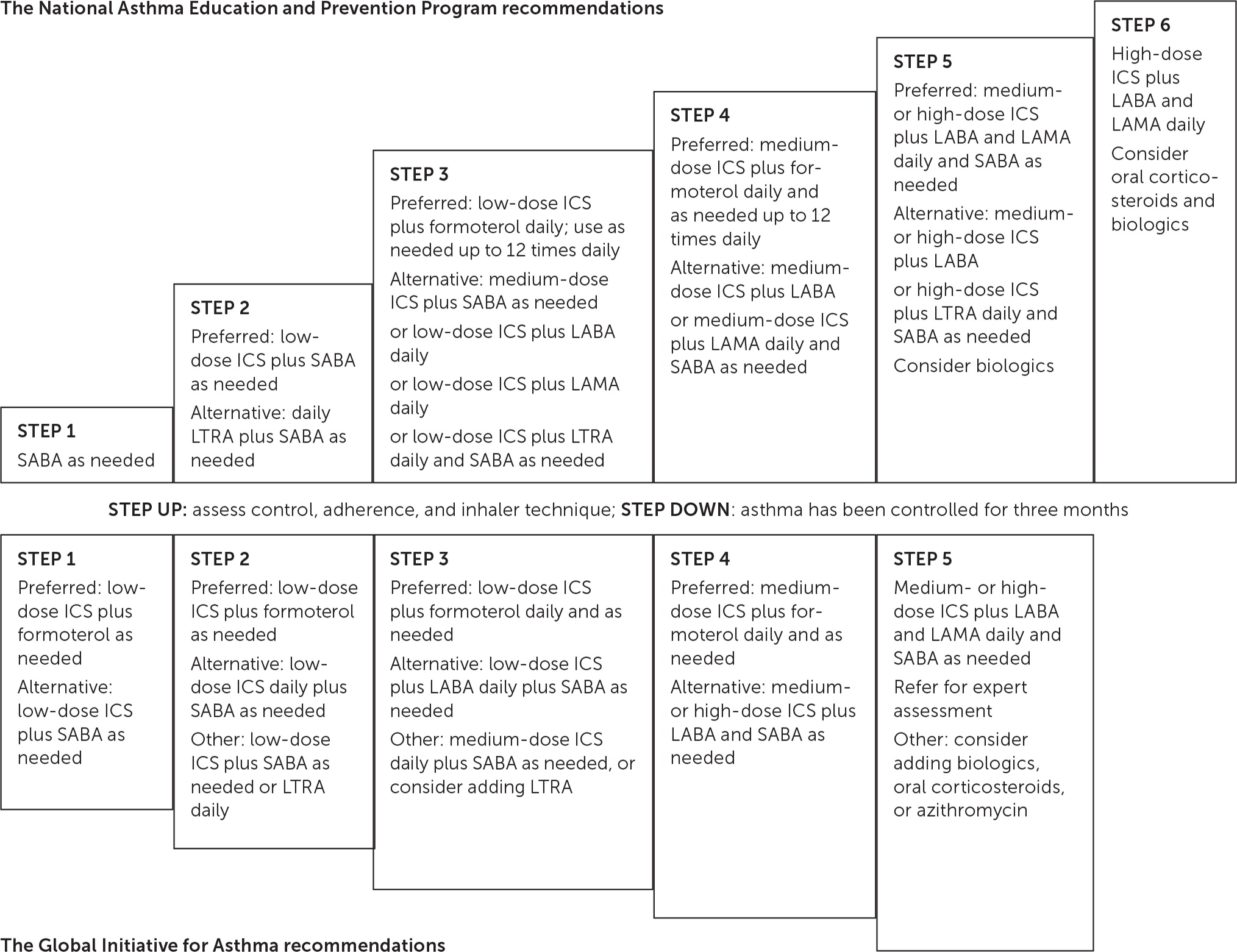

After severity and control are evaluated, a stepwise treatment plan may be implemented using the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) or NAEPP guidelines (Figure 12,5,7). Spirometry is recommended for all patients at diagnosis; weak evidence supports repeating spirometry in patients with worsening symptom control.2,3 Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) is an independent predictor of asthma exacerbations. Patients with an FEV1 of less than 60% are twice as likely to experience an exacerbation compared with those who have an FEV1 of more than 80%.5

Other objective measures of asthma severity show limited effectiveness in guiding treatment. Therapy guided by fractional excretion of nitric oxide reduced asthma exacerbations in children and adults (odds ratio [OR] = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.51 to 0.90).3 However, because strategies based on fractional excretion of nitric oxide showed no correlation with improvements in symptom control or quality of life, this therapy is not recommended for use without other adjuncts.7 Treatment guided by sputum eosinophils reduces exacerbations in adults (OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.86), although this outcome is questionable because there were no group differences in clinical symptoms, quality of life, or spirometry.8

What Are the Benefits and Harms of Each Major Class of Asthma Medications?

Table 2 lists common pharmacologic treatment options for chronic asthma.2,7–18 Asthma medications are divided into relievers and controllers. Relievers (i.e., rescue medications) are used as needed to treat acute symptoms of asthma by improving airflow. Controllers (i.e., maintenance medications) are used daily to improve airflow, decrease hospitalizations, reduce exacerbations, and lessen reliever use. Adverse effects are typically mild with usual dosages.

| Class | Drug | Benefits | Common adverse effects* | Significant adverse effect considerations | FDA boxed warning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relievers | |||||

| Short-acting beta2 agonists | Albuterol, levalbuterol (Xopenex) | Improves FEV1 | Asthma exacerbation, excitement, nervousness, pharyngitis, rhinitis, upper respiratory tract infection | Cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac ischemia, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, paradoxical bronchospasm, tachycardia | — |

| Short-acting muscarinic antagonists | Ipratropium (Atrovent) | Improves FEV1 | Bronchitis, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sinusitis | Blurred vision, dizziness, hypersensitivity reaction, paradoxical bronchospasm | — |

| Controllers | |||||

| Inhaled corticosteroids | Fluticasone (Flovent), budesonide, ciclesonide, mometasone | Reduces symptoms and reliever use; reduces hospitalizations and exacerbations; improves FEV1 | Arthralgia, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, nasal congestion, oral candidiasis, sinusitis, throat irritation, upper respiratory tract infection | Adrenal suppression, cataracts, glaucoma, hypersensitivity reaction, immunosuppression, osteopenia, paradoxical bronchospasm, reduction in growth velocity (children), vasculitis | — |

| Long-acting beta2 agonists | Salmeterol (Serevent), formoterol (Foradil) | Reduces symptoms and reliever use; reduces hospitalizations and exacerbations; improves FEV1 | Headache, musculoskeletal pain | Hypersensitivity reaction, paradoxical bronchospasm | Use as monotherapy increases the risk of asthma-related death |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonists | Tiotropium (Spiriva) | Reduces exacerbations; improves FEV1 | Pharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, xerostomia | Hypersensitivity reaction, paradoxical bronchospasm | — |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists | Montelukast (Singulair), zafirlukast (Accolate) | Reduces exacerbations; improves FEV1 | Headache | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, hepatotoxicity, upper respiratory tract infection | Serious neuropsychiatric events, including suicide (montelukast only) |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Short-acting beta2 agonists (SABAs) are reliever medications and are preferred for treating acute asthma symptoms and exacerbations. SABAs demonstrate improvement in FEV1 within three to five minutes with minimal adverse effects.2 Short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMAs) improve FEV1 but are not used as monotherapy because of a slower onset of action.5 SAMAs combined with SABAs decrease hospitalizations for severe exacerbations (relative risk [RR] = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.87) but do not reduce hospital length of stay or need for supplemental therapy compared with SABAs alone.9

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are the most effective controller medications; they decrease asthma exacerbations (RR = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.62), hospitalization rate (RR = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.6), and the need for reliever medications.10–12 Common adverse effects are localized and minimal.2 Studies have shown that prolonged use of a high-dose ICS (i.e., more than 1 mg per day for at least three years) may increase the risk of cataract formation in adults (OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.37).19 Evidence regarding adrenal suppression and decreased linear growth due to ICS use in children is mixed. Ongoing treatment with a high-dose ICS in children can cause statistically, but not clinically, significant reductions in cortisol production.20 Although a reduced linear growth velocity of 0.48 cm per year has been detected in children using an ICS, it does not persist into adulthood or alter final height.21–23

Long-acting beta2 agonists (LABAs) are the first-choice add-on controller medication for use with an ICS. Studies show reductions in exacerbations (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.64 to 0.84), reliever medication use (1.2 puffs per day; 95% CI, 1 to 1.4 puffs per day), and nocturnal awakenings.13,14 LABA monotherapy carries a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) boxed warning because of data associated with increased risk of death, intubation, and hospitalization and is not recommended. There is no evidence that a combination of an ICS plus a LABA increases the risk of serious asthma-related events compared with an ICS alone.24–26

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) and leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) are second-line controller therapies. LAMAs decrease exacerbations in combination with an ICS (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.92) but have an inferior benefit-to-harm ratio compared with ICS/LABA combinations. Adding LAMAs to ICS/LABA combinations improves symptom control for severe persistent asthma.3

LTRAs reduce asthma exacerbations (RR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.81) as monotherapy; however, they are only half as effective as an ICS. LTRAs may be used as an alternative monotherapy in mild persistent asthma or as an adjunct for more severe disease, and they are effective at controlling exercise-induced bronchospasm.2,15,16 LTRAs are usually well-tolerated with only case reports documenting severe adverse effects. Montelukast (Singulair) carries an FDA boxed warning about behavior and mood-related changes, including suicide.17

What Combinations of Medications Are Used When Inhaled Corticosteroids Alone Do Not Adequately Relieve Symptoms?

Options for patients with asthma that is not adequately controlled on ICS monotherapy include increasing the dose of the ICS or adding a LABA, LAMA, or LTRA. Evidence is strongest for using an ICS plus a LABA for adolescents and adults, whereas increasing the dose of the ICS is recommended in children. An ICS plus an LTRA is inferior to an ICS plus a LABA but comparable to increasing the dose of the ICS. LAMAs may be useful as an adjunct to ICS/LABA combinations.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients who have inadequate asthma control with an ICS alone should be evaluated for modifiable risk factors (Table 32,5). If behavioral modifications do not improve symptoms and control, the medication regimen should be adjusted.5 Options include increasing the dose of the ICS or adding an adjunct in the form of a LABA, LAMA, or LTRA. Studies measuring treatment outcomes typically assess one or more of the following: lung function using FEV1 or morning peak expiratory flow, asthma exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids, hospitalizations, or surveys evaluating symptom control and quality of life.27

| Risk factor | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Comorbidities | Patients should be screened and appropriately treated for comorbid conditions that worsen asthma symptoms, such as obstructive sleep apnea, rhinitis or sinusitis, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression. Optimal treatment of comorbid conditions may improve asthma symptoms. |

| Environmental exposures and allergens | Referral to a specialist for evaluation of allergens should be considered if there is concern that they may be worsening asthma symptoms. Potential occupational exposures should be reviewed with all adults. |

| Incorrect diagnosis of asthma | Diagnostic history of asthma should be reviewed with patient and families if there is an inadequate response to treatment after inhaler technique and medication adherence have been appropriately addressed. At the time of diagnosis, children six years and older, adolescents, and adults should have spirometry testing and documentation of excessive variability in lung function. If the diagnosis of asthma is not confirmed (as is the case with 25% to 35% of patients with a diagnosis of asthma in primary care), a stepwise approach may be needed for diagnosis. This usually involves decreasing intensity of treatment to determine if asthma symptoms persist or worsen. For adults, a methacholine challenge test can evaluate for airway hyperresponsiveness if inhaled corticosteroids are discontinued. It is important to rule out alternative causes of asthma-like symptoms such as cystic fibrosis, inhaled foreign bodies, congenital heart disease, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other lung diseases. |

| Medications that worsen asthma | Common medications that can worsen asthma symptoms include nonselective beta blockers, aspirin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinicians should discuss cardioselective beta blockers with appropriate specialists if indicated. |

| Poor inhaler technique | This occurs in up to 80% of community-dwelling patients. Clinician educators should demonstrate inhaler method and ask the patient to repeat the technique three times to ensure correct use at initial visit. If a metered dose inhaler is used, patients should use a spacer to deliver medication. At follow-up visits, clinicians should ask patients to show how they use the inhaler, rather than asking if they are using it. |

| Poor medication adherence | This occurs in approximately 50% of adults and children on long-term asthma therapy. Clinicians can identify poor adherence by reviewing refill records and discussing adherence in patient visits. Issues that lead to poor adherence should be discussed without blaming and options to overcome barriers should be offered. For example, a school nurse can directly observe therapy in children with asthma. Some patients may benefit from dosing once daily instead of twice daily. |

| Tobacco use | Family members and caregivers who smoke should be advised not to allow smoking in rooms or cars that children use. They should be encouraged to quit given the impact of passive smoke on patients with asthma. Available options include smoking cessation programs, counseling, and medications such as varenicline (Chantix), bupropion (Zyban), and nicotine replacement therapy. Once passive exposure is eliminated, patients with asthma experience improved asthma control and reduced hospital admissions. If the patient with asthma smokes, they should be strongly encouraged to quit at every visit. The same smoking cessation modalities may be offered to patients with asthma. |

For adults and adolescents, an ICS/LABA combination is the preferred step-up therapy because it reduces the risk of exacerbations, improves lung function and symptoms, and leads to decreased use of rescue inhalers.28 RCTs comparing ICS/LABA combinations with doubling the dose of an ICS showed no significant difference in the rate of exacerbations requiring corticosteroids. For children using the same dose of an ICS and adding a LABA, there was a trend toward increased risk of hospitalizations; however, this was not statistically significant.29 More research is needed on using ICS/LABA combinations in children younger than 12 years.

LAMAs are typically added as adjuncts for patients on a daily combination of an ICS plus a LABA. In adults with uncontrolled asthma taking an ICS/LABA, the addition of tiotropium (Spiriva) may slightly improve lung function and decrease the need for oral corticosteroids for exacerbations.30 For patients on ICS monotherapy, it is unclear if doubling the ICS dose vs. keeping the same ICS dose and adding a LAMA provides clinical benefit because results from RCTs are inconclusive.31 Data are insufficient to compare ICS/LABA combinations with ICS/LAMA combinations.32 For children six to 18 years of age with moderate to severe asthma on an ICS/LABA combination, increasing to an ICS/LABA/LAMA combination resulted in fewer severe exacerbations and improvements in asthma control.32

When Is Single Maintenance and Reliever Therapy Recommended?

Single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) is the preferred treatment for moderate asthma in adolescents and adults because of its effectiveness at reducing severe exacerbations.2,31,36 It should be considered for mild asthma when patients are unable to adhere to daily controller therapy and are at risk of overusing SABAs, which have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality.5 Most RCTs evaluating SMART used budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort). There is insufficient evidence for SMART in children younger than 12 years.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

SMART uses an ICS/LABA combination for daily controller therapy and as-needed reliever therapy.36 Formoterol is a fast-acting beta2 agonist and the recommended LABA for this approach because its onset of action is similar to that of SABAs.37 According to NAEPP and GINA guidelines, SMART is preferred for moderate asthma in adolescents and adults.5,7 In a meta-analysis of RCTs, SMART resulted in a lower risk of asthma exacerbations, although it had no effect on frequency of reliever inhaler use. The lower risk of asthma exacerbations with SMART is thought to be because of early exposure to corticosteroids and an earlier reduction in airway inflammation compared with as-needed SABA therapy.36 In a meta-analysis of observational and interventional studies that compared SMART with daily ICS/LABA combinations plus SABA therapy, SMART was correlated with a reduction of severe exacerbations.38 This meta-analysis included two studies with high-to-critical risk of bias, and the authors received funding from the pharmaceutical industry.38 For children four to 11 years of age with moderate asthma, SMART reduced the risk of exacerbations compared with ICS monotherapy; however, data are insufficient to make this the preferred therapy for children.5,36

Although GINA recommends SMART for moderate asthma in adolescents and adults (steps 3 and 4), as-needed ICS/LABA combinations are recommended as first-line therapy for mild asthma (steps 1 and 2) in these age groups.5 A 2021 Cochrane review concluded that as-needed budesonide/formoterol reduced exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids, asthma-related hospital admissions, and emergency department or urgent care visits compared with as-needed SABA for mild asthma.37 SMART may improve outcomes for patients with low adherence to daily controller therapy because these patients are at risk of overusing SABAs. Frequent SABA use results in worse outcomes, including asthma exacerbations and death.5

Multiple clinical trials provide evidence to support the use of SMART for the treatment of asthma, but there remains a paucity of data for use in primary care. In an analysis of prescribing patterns in the United Kingdom, 14,818 patients were prescribed a budesonide/formoterol fixed-dose inhaler, but only 173 patients were prescribed SMART dosing. Of those 173 patients, 91 were prescribed a SABA the following year.39 More studies are needed to determine if evidence from RCTs effectively translates into real world practice with improved patient outcomes such as reduced asthma exacerbations.

Is There a Role for Allergen Immunotherapy?

Subcutaneous immunotherapy may be considered for individuals five years and older with mild to moderate allergic asthma but should be avoided in those who have severe asthma.40–43 It offers small improvements in symptoms and medication use, but its utility is limited because of the slight risk of harm and variable access for patients. Sublingual immunotherapy is not recommended for the management of asthma but may be helpful for individuals with certain allergies.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Allergic asthma is defined as asthma symptoms that occur with exposure to allergens and evidence of sensitization to allergen skin testing or in vitro serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) testing.7 The 2020 NAEPP guidelines conditionally recommend subcutaneous immunotherapy as an adjunct treatment for people five years and older with mild to moderate allergic asthma.7 There are three requirements for this recommendation: (1) asthma should be optimally controlled at the initiation, build-up, and maintenance phases of immunotherapy; (2) it should be completed under the direct supervision of a clinician; and (3) it requires shared decision-making. The recommendation is conditional because of the potential for health inequalities based on costs and access to these services.

A recent meta-analysis showed that allergen immunotherapy improved symptom scores with a standardized mean difference (SMD) of −1.11 (95% CI, −1.66 to −0.56) and reduced medication use with an SMD of −1.21 (95% CI, −1.87 to −0.54).39 Subcutaneous immunotherapy was more effective than sublingual immunotherapy, and improvements with sublingual immunotherapy were not statistically significant. Reductions in symptom scores showed an SMD of −0.58 (95% CI, −1.17 to −0.01) in children and −1.95 (95% CI, −3.28 to −0.62) in adults. No studies reported long-term effectiveness of allergen immunotherapy on asthma control, exacerbations, or lung function.

In children, there is moderate-strength evidence that subcutaneous immunotherapy reduces long-term asthma medication use and low-strength evidence that it reduces asthma-related quality of life and FEV1.41 Sublingual immunotherapy is not approved by the FDA or recommended in asthma management. Evidence is insufficient to determine clinical effectiveness, although it appears to be safe.42,43

What Are the Options for Patients With Severe Asthma?

For patients with severe uncontrolled asthma despite taking a combination of an ICS plus a LABA with other controller medications, serum IgE and blood eosinophils should be measured and specialty referral considered. IgE antagonists, interleukin-5 antagonists, and interleukin-4/13 antagonists reduce exacerbations and may reduce oral corticosteroid use with favorable adverse effect profiles.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Severe asthma is asthma that remains uncontrolled despite treatment with a high-dose ICS combined with a LABA, LAMA, or LTRA for the past year or regular use of oral corticosteroids.44 For these patients, clinicians should first confirm the diagnosis, assess adherence to optimized controller inhalers, and manage relevant comorbidities and aggravating factors.44 If there is a poor response to these measures, their asthma is likely mediated by IgE or type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Clinicians should consider ordering serum IgE levels and blood eosinophils to optimize specialty referral and target biologic therapies. Biologic agents for severe uncontrolled asthma are shown in Table 4.18,45,46 Oral corticosteroids at the lowest effective dose are the mainstay of treatment for patients with severe asthma.3 However, their use is limited by significant adverse effects.

| Class | Drug | Indications | Adverse effects | FDA boxed warning | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoglobulin E antagonists | Omalizumab (Xolair) | Treatment of moderate to severe persistent asthma in adults and children six years and older who have a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen and whose symptoms are inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids | Alopecia, anxiety, arthralgia, asthma, bone fracture, cough, dermatitis, dizziness, epistaxis, fatigue, fever, fungal infection, headaches†, limb pain, local injection site reactions†, migraine, musculoskeletal pain, myalgia, nasopharyngitis, oropharyngeal pain, otalgia, otitis media, peripheral edema, sinus headache, sinusitis, streptococcal pharyngitis, toothache, upper abdominal pain, upper respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, urticaria, viral gastroenteritis, viral upper respiratory tract infection | Risk of anaphylaxis; omalizumab therapy should be initiated in a health care setting and patients closely observed for an appropriate period of time after administration | Only available through specialty pharmacies |

| Interleukin-4/13 antagonists | Dupilumab (Dupixent) | Treatment of moderate to severe eosinophilic or oral glucocorticoid– dependent asthma; add-on maintenance treatment for moderate to severe asthma in adults and children six years and older with an eosinophilic phenotype or corticosteroid-dependent asthma | Antibody development†, arthralgia, conjunctivitis, eosinophilia, gastritis, helminthiasis, insomnia, local injection site reactions†, oral herpes simplex infection, oropharyngeal pain, toothache | — | Only available through specialty pharmacies |

| Interleukin-5 antagonists | Benralizumab (Fasenra) | Add-on maintenance treatment for severe asthma in adults and children 12 years and older with an eosinophilic phenotype | Antibody development†, fever, headache, pharyngitis | — | — ($5,015) |

| Mepolizumab (Nucala) | Add-on maintenance treatment for severe asthma in adults and children six years and older with an eosinophilic phenotype | Angioedema, antibody development, arthralgia, diarrhea, dry nose, eczema, fatigue, fever, hypersensitivity reaction, headache†, influenza, local injection site reactions†, oropharyngeal pain, urinary tract infection | — | Only available through specialty pharmacies | |

| Reslizumab (Cinqair) | Add-on maintenance treatment for severe asthma in adults with an eosinophilic phenotype | Antibody development, increased creatine phosphokinase, myalgia, oropharyngeal pain | Patients should be observed for anaphylaxis by a health care professional for an appropriate period of time after reslizumab administration | Only available through specialty pharmacies |

Omalizumab (Xolair) is an IgE antagonist. Allergic asthma mediated by IgE is estimated to account for more than 50% of difficult-to-control asthma cases.47 A recent meta-analysis of RCTs confirmed its effectiveness.48 Omalizumab significantly reduced annual severe exacerbations (RR = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.56) and the proportion of patients receiving oral corticosteroids (RR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.75). It also improved FEV1 and symptom scores.

Interleukin-5 antagonists are approved for severe eosinophilic asthma (i.e., blood eosinophil count of 300 per μL [0.3 × 109 per L] or more) and reduce the rates of asthma exacerbations by approximately 50% in patients on at least two controller medications.49 For patients with severe eosinophilic asthma, the interleukin-4/13 antagonist dupilumab (Dupixent) reduced the annual rate of severe asthma exacerbations (65.8% lower with dupilumab than with placebo; 95% CI, 52.0% to 75.6%).50 Dupilumab also resulted in better lung function and asthma control. A Cochrane review suggested that interleukin-4/13 agents lead to a reduction in exacerbations requiring hospitalization or emergency visits, at the cost of increased adverse effects and no clinically relevant improvements in health-related quality of life or asthma control.45 Cost and parenteral formulations limit their use for some patients.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Falk, et al.51; Elward and Pollart52; Mintz53; and Gross and Ponte.54

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms asthma and medications. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Cochrane database, Trip database, ECRI Guidelines Trust, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: December 7, 2021, to February 13, 2022, and February 28, 2023.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the U.S. Department of the Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.