Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(6):560-565

Published online May 14, 2024.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Gender-affirming surgery includes a range of procedures that help align a transgender or gender diverse person's body with their gender identity. As rates of gender-affirming surgery increase, family physicians will need to have the knowledge and skills to provide lifelong health care to this population. Physicians should conduct an anatomic survey or organ inventory with patients to determine what health screenings are applicable. Health care maintenance should follow accepted guidelines for the body parts that are present. Patients do not require routine breast cancer screening after mastectomy; however, because there is residual breast tissue, symptoms of breast cancer warrant workup. After masculinizing genital surgery, patients should have lifelong follow-up with a urologist familiar with gender-affirming surgery. If a prostate examination is indicated after vaginoplasty, it should be performed vaginally. If a pelvic examination is indicated after vaginoplasty, it should be performed with a Pederson speculum or anoscope. After gonadectomy, patients require hormone therapy to prevent long-term morbidity associated with hypogonadism, including osteoporosis. The risk of sexually transmitted infections may change after genital surgery depending on the tissue used for the procedure. Patients should be offered the same testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections as cisgender populations, with site-specific testing based on sexual history. If bowel tissue is used in vaginoplasty, vaginal bleeding may be caused by adenocarcinoma or inflammatory bowel disease. (Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(6):560-565. Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

| In a 2015 cross-sectional volunteer sample survey of more than 27,000 transgender and gender diverse adults in the United States, 25% of respondents reported having had some type of gender-affirming surgery in the past, and more than 25% wanted surgery in the future. |

| Gender-affirming surgery has been shown to improve quality of life, has comparable rates of complications with procedures performed for non–gender-affirming indications, and is associated with low rates of regret. |

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people are those whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. Cisgender people are those whose gender identity does align with the sex they were assigned at birth. TGD people comprise 0.4% to 2.7% of the U.S. population.1,2 Gender-affirming surgery includes a range of procedures that help align a patient's body with their gender identity (Table 1). Some TGD people choose to have gender-affirming surgery, although not all. The number of patients who seek gender-affirming surgery has increased.3 It has been shown to improve quality of life, has comparable rates of complications to similar procedures performed for non–gender-affirming indications, and is associated with low rates of regret.4

| Surgery | Commonly known as | Commonly performed by |

|---|---|---|

| Facial procedures | ||

| Blepharoplasty | Facial feminization surgery (or FFS) | Plastic surgery |

| Brow reduction, augmentation, or lift | ||

| Cheek implant | ||

| Facelift | ||

| Hairline advancement | ||

| Jaw reduction and chin reshaping | ||

| Lip augmentation or shortening | ||

| Rhinoplasty | ||

| Neck procedures | ||

| Chondrolaryngoplasty | Tracheal shave | Ear, nose, and throat or |

| Vocal surgery (pitch raising) | Vocal surgery | plastic surgery |

| Chest procedures | ||

| Breast augmentation | Top surgery | Plastic surgery |

| Chest masculinizing mastectomy | ||

| Genital procedures | ||

| Metoidioplasty (with or without scrotoplasty) | Bottom surgery | Plastic surgery or a multidisciplinary team with plastic surgery, urology, and/or obstetrics and gynecology |

| Phalloplasty (with or without scrotoplasty) | ||

| Vaginoplasty | ||

| Vulvoplasty | ||

| Gonadectomy | ||

| Hysterectomy (with or without salpingo-oophorectomy) | Bottom surgery | Obstetrics and gynecology or urology |

| Orchiectomy | ||

| Vaginectomy | ||

| Body Contouring | ||

| Liposuction | Body contouring | Plastic surgery |

| Muscle implants |

Gender-affirming surgery is a rapidly growing field. Acceptance of TGD people and insurance coverage for gender-affirming surgery are increasing; therefore, more surgeons are offering these procedures.1 In a 2015 cross-sectional volunteer sample survey of more than 27,000 TGD adults in the United States, 25% of respondents reported having had some type of gender-affirming surgery in the past, and more than 25% wanted some type of gender-affirming surgery in the future.5 As the number of people who get gender-affirming surgery increases, primary care physicians will need to be equipped with the knowledge and skills to provide lifelong health care to this population. Lack of physician knowledge and omission of TGD-related issues in medical school curricula remain significant barriers.6,7

Experts are often not available locally, and patients may rely on their primary care physician to navigate postoperative care and recovery.8 Physicians should conduct an anatomic survey or organ inventory with TGD patients to determine what health screenings are applicable4,9,10 (Table 2). In general, physicians should perform health care maintenance in accordance with accepted guidelines for the body parts that are present.4,10

| To guide your health care and preventive screenings, please circle the body parts you have and include any different words you use for these body parts: |

| Breasts ________________________________________________ |

| Uterus ________________________________________________ |

| Ovaries ________________________________________________ |

| Cervix ________________________________________________ |

| Vagina ________________________________________________ |

| Penis ________________________________________________ |

| Testes ________________________________________________ |

| Prostate ________________________________________________ |

This article provides an overview of gender-affirming surgery with a focus on anatomic changes, how to perform routine physical examinations, and how gender-affirming surgery may alter a patient's care throughout their life. Management of major perioperative complications and counseling and evaluation before surgery are beyond the scope of this article. Care after breast augmentation is covered in a previous American Family Physician article and can be applied to TGD people.11 Other aspects of caring for TGD people, including creating an affirming clinic environment, health maintenance, and hormone therapy are also covered in previous American Family Physician articles.12,13

Masculinizing Chest Surgery

Masculinizing chest surgery is performed using different techniques to remove breast tissue and create a masculine chest appearance. The most common approach is a double incision mastectomy with free nipple grafts.14 Complications are usually minor and limited to the immediate postoperative period.15,16

Physicians should inform patients that masculinizing chest surgery does not eliminate the risk of developing breast cancer.17 There is no reliable evidence to guide breast cancer screening for TGD people who have undergone mastectomy or chest contouring. All surgical approaches leave some residual breast tissue for satisfactory cosmetic results, and the risk of breast cancer in residual tissue is unknown. There are case reports of breast cancer among TGD patients who have undergone chest surgery.18–20

The American College of Radiology recommends against routine breast cancer screening in transmasculine individuals of any age and risk who have undergone gender-affirming mastectomy.21 Physical examination and diagnostic imaging are appropriate for new symptoms, including chest masses, axillary lymph nodes, nipple retraction, or skin changes. Mammography is usually not feasible due to the removal of most breast tissue. Alternatives, such as ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging, can be used to evaluate palpable findings.22 Physicians should collaborate with local radiologists to determine optimal imaging based on patient anatomy.

Masculinizing Genital Surgery

Masculinizing genital surgery includes a variety of procedures to construct masculine genitalia. These fall broadly into two categories: metoidioplasty and phalloplasty.23 Surgeries are typically done in stages to mitigate complications. Specific procedures and techniques may be combined based on patient goals, including standing micturition, aesthetic appearance, tactile sensation, and sexual function. Testosterone therapy is generally recommended before these procedures.4

Metoidioplasty releases and elongates the hormonally hypertrophied native clitoral tissue.24 Metoidioplasty may be done with or without hysterectomy and vaginectomy. If standing micturition is desired, surgeons can use labial tissue to elongate the urethra.24 Phalloplasty uses free or pedicle flaps to construct a phallus. If standing micturition is desired after phalloplasty, hysterectomy and vaginectomy are typically required for urethral elongation.25,26 Radial forearm free flap is the most common technique, although other sites may be used. Implantation of a penile prosthetic to allow for erectile and sexual function may be included.27

Urethral complications may present weeks to years after surgery and commonly include urethrocutaneous fistulas, urethral strictures, and a persistent vaginal cavity.28 Due to the complex nature of these surgeries and the potential for complications, patients should have ongoing follow-up with a urologist who is familiar with gender-affirming surgery.4 Symptoms of urinary retention, postvoid dribbling, pelvic pain with fullness, or recurrent urinary tract infections should prompt referral to urology. Long-term complications of the donor site for phalloplasty include nerve injury, decreased strength, and decreased sensation.29 Occupational therapy referral can be helpful for those with radial forearm donor site complications.

For patients who have had metoidioplasty without vaginectomy and have receptive vaginal sex, testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) should be performed with physician-or patient-collected vaginal swabs. Due to anatomic changes from surgery, urine specimens are inadequate to detect cervical infections.30 Examinations with a speculum can be difficult after metoidioplasty due to narrowing of the introitus.

Hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy is the same procedure regardless of the patient's gender identity. Cervical cancer screening after hysterectomy should follow guidelines, such as those from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, which apply to anyone who has or previously had a cervix, including TGD people.4,31 Human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer with self-collected swabs may be an acceptable option in transmasculine people who decline speculum examinations.32

If both ovaries are removed at a premenopausal age, hormone therapy is needed to prevent morbidity from hypogonadism.33 Typically, testosterone is prescribed. If patients do not desire or have not previously used testosterone, the ovaries are usually left in place. There is no guideline or consensus on age thresholds for when hormone therapy is no longer needed or when it can be stopped; it is typically continued throughout life.4 This can be decided through shared decision-making between the patient, surgeon, and the physician who is managing the patient's hormone therapy.

Feminizing Genital Surgery

Feminizing genital surgery includes a range of procedures that are selected based on patient preference and chronic medical conditions. Removal of the gonads can be used as a stand-alone procedure for antiandrogenic effect. If orchiectomy is performed as a first step toward an intended future vaginoplasty, the scrotal skin is left intact for use in future reconstruction.34 Use of estradiol hormone therapy for at least 6 months is recommended before gonadectomy to ensure it is desired and tolerated.4 After gonadectomy, patients require hormone therapy to prevent long-term morbidity associated with hypogonadism, including osteoporosis.4,33 Typically, estradiol is used. Similar to hormone management after masculinizing genital surgery, there is no guideline or consensus on age thresholds for when hormone therapy is no longer needed. It is usually continued throughout life. Shared decision-making with the patient, surgeon, and the physician who is managing the patient's hormone therapy should be used.

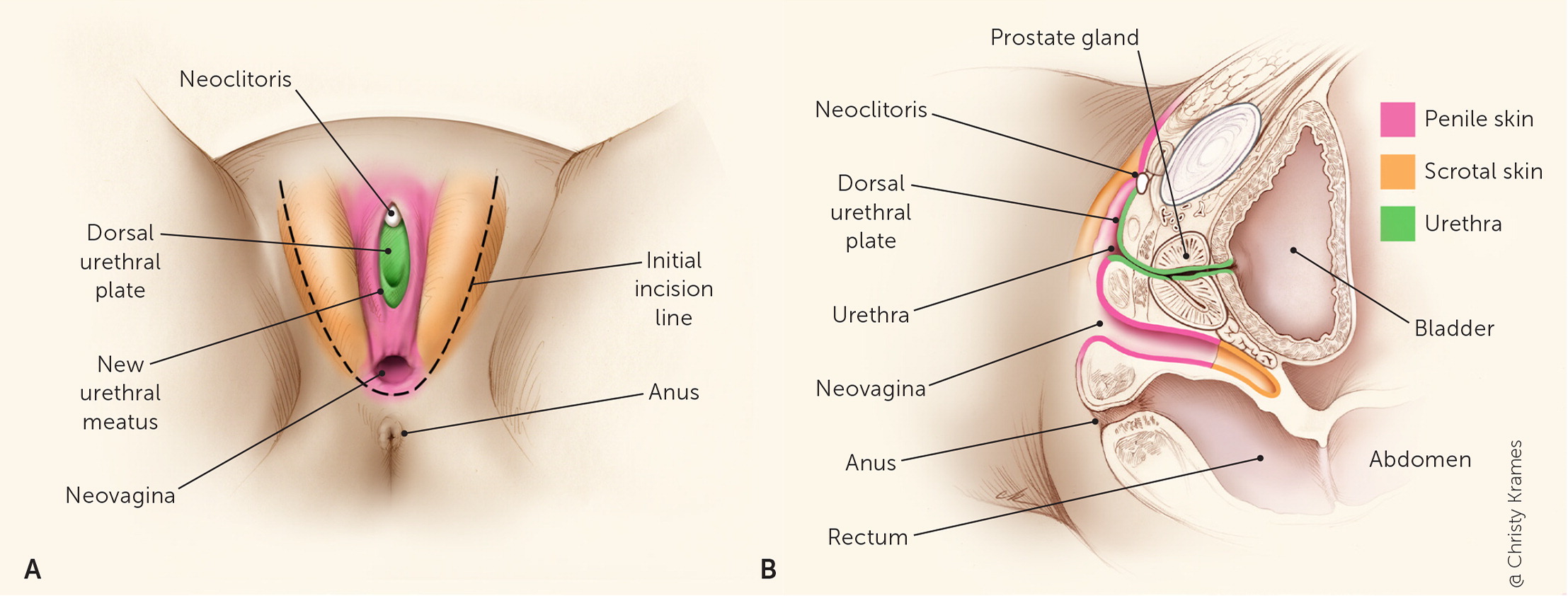

Vaginoplasty is a reconstructive surgery used to create aesthetically accurate and functional feminine genitalia. Functional goals include urination, orgasm, and receptive vaginal penetration. The most common and well-documented feminizing genital surgery is penile inversion vaginoplasty, which inverts the skin of the penis and testes to create a vaginal canal between the bladder and rectum.35 There are variations of feminizing genital surgery that use other tissue types to line the vaginal space, including the peritoneum and colon. There is also the option of a zero-depth vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty, in which no vaginal canal is built.36 After feminizing genital surgery, except with simple orchiectomy, a patient will have a vulva with a urethra and clitoris, a prostate left in situ, and may have a vaginal canal (Figure 1). If indicated, prostate examinations are performed vaginally, not rectally, because the prostate is anterior to the constructed vagina.37 Patients should follow up with their surgeon regularly, but this is typically not required beyond the first year.4

Postoperative complications of vaginoplasty can vary in severity and timing of presentation. Minor complications include granulation tissue and hair regrowth in the vaginal canal. More serious and rare complications include hematoma, abscess, large wound dehiscence, skin graft or flap necrosis, and rectovaginal fistulas. These serious complications may require a warm handoff and should be managed by a surgical team.38

The constructed vagina requires lifelong dilation performed by the patient at home with vaginal dilators to maintain patency. Permanent vaginal stenosis is a complication of not dilating. Long-term sexual dysfunction such as anorgasmia and the inability to have receptive vaginal penetration are possible.38 New vaginal symptoms should prompt a pelvic examination. The vaginal canal should accommodate a Pederson speculum; however, an anoscope is a more slender alternative.37 It is reasonable to consider pelvic examinations yearly or every other year to monitor for complications, including stenosis, granulation tissue, or hair regrowth.

The constructed vagina is most often skin lined and colonized by a combination of skin flora and vaginal species. Vaginal discharge or odor is commonly due to dead skin, sebum, or retained lubricant. Douching with soapy water or a dilute vinegar and betadine solution is typically adequate to maintain hygiene. An empiric 5-day course of vaginal metronidazole (Flagyl) is reasonable for persistent odor.39 Genitourinary infections, such as urinary tract infections, STIs, and vaginitis, can be treated using the same guidelines for cisgender patients.4 The risk of STIs may differ depending on the tissue used to create the vagina and sexual practices. There are case reports of multiple bacterial and viral STIs occurring in a surgically constructed vagina.40–42 Patients should be offered the same testing and treatment for STIs as cisgender populations, with site-specific testing based on symptoms and sexual history.30

The urethra is shortened in feminizing genital surgery, making urinary tract infections more common postoperatively.43 Urinary incontinence is rare and should be referred to a urologist or the surgical team.28 Most patients are able to have an orgasm after surgery; however, libido can decrease after gonadectomy. Libido can be improved with sex therapy, self-stimulation, or adding a low dose of testosterone.44,45 Loss of vaginal depth or girth can occur. Increasing the frequency of dilation, especially with the help of a pelvic floor physical therapist, is first-line treatment for vaginal stenosis.46 Persistent genital pain or difficulty dilating should be referred to the surgeon. If peritoneum or colon tissue is used, bowel pathology, such as adenocarcinoma and inflammatory bowel disease, may present as vaginal bleeding from lesions that should be biopsied.47–49

Other Gender-Affirming Surgery

Other surgical procedures are used to meet a patient's goals, including breast augmentation, feminizing and masculinizing facial procedures, vocal cord surgery, and body contouring. Although these procedures have risks and complications, they do not change indicated routine care or physical examinations.

Data Sources: A search of PubMed and Embase was performed with key words gender-affirming surgery, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, and vaginoplasty. The search included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, original research articles, and review articles. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: May through July 2023, and April 2024.