This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2024;110(5):487-492

Author disclosure: No financial relationships.

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 or 2. It affects at least 500 million people worldwide and is a lifelong condition involving initial infection and periodic reactivation with variable viral shedding. There are no vaccinations for the prevention of HSV, and routine serologic screening is not recommended in asymptomatic individuals. Practices that prevent or reduce transmission include the use of suppressive antiviral therapy in serodiscordant partners, avoiding sexual contact during outbreaks, and use of condoms. A clinically apparent herpes outbreak is characterized by painful vesicles on the genitals, rectum, or perineum and may be accompanied by a flulike syndrome of fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Diagnosis uses type-specific polymerase chain reaction, viral culture of active lesions, or type-specific serologic testing. Nucleoside analogue medications reduce viral shedding and are used to treat active outbreaks and prevent recurrences. Complications of genital herpes include encephalitis, meningitis, and urinary retention. During pregnancy, antiviral suppression is recommended starting at 36 weeks of gestation in patients with a known history of genital herpes. Elective cesarean delivery should be offered to patients with active lesions to reduce neonatal exposure to HSV.

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 or 2. It is the most common cause of genital ulcers in the United States.1 This article briefly summarizes and reviews the best available patient-oriented evidence for genital herpes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

HSV-2 almost exclusively causes genital ulcers and affects an estimated 491.5 million people ages 15 to 49 worldwide (13% of the population).2

HSV-1 typically causes orolabial lesions but also causes genital ulcers in an estimated 190 million people worldwide.2

In the United States, there are 572,000 new cases of genital herpes annually, and 11.9% of individuals ages 14 to 49 are infected with HSV-2.3,4

At least one-half of new genital herpes cases are attributable to HSV-1.4 This appears to be associated with decreased seroprevalence of HSV-1 due to fewer childhood exposures to orolabial herpes.4

Risk factors associated with genital herpes are listed in Table 1.5–7

| Risk factor | Risk increase |

|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis5 | Increases genital tract shedding of HSV-2 (adjusted OR = 2.3; 95% CI, 1.3–4.0) |

| Group B streptococcus colonization5 | Increases genital tract shedding of HSV-2 (adjusted OR = 2.2; 95% CI, 1.3–3.8) |

| Hormonal contraceptive use5 | Increases genital tract shedding of HSV-2 (adjusted OR = 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–2.8) |

| HSV-2 seropositivity6 | Increased risk of HIV acquisition Men: summary adjusted RR = 2.7 (95% CI, 1.9–3.9) Women: summary adjusted RR = 3.1 (95% CI, 1.7–5.6) Men who have sex with men: summary adjusted RR = 1.7 (95% CI, 1.2–2.4) |

| Oral-genital contact7 | Increased risk of transmitting HSV-1 from latent or active infection at the oral site to the genital site |

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against routine serologic screening for genital herpes in asymptomatic adults, adolescents, and pregnant people with no known history of genital herpes.8,9

The moderate risk of harm from high false-positive rates, which may lead to psychosocial disruption and unnecessary antiviral suppression therapy, outweighs the potential small benefits of screening in asymptomatic people.9

Primary prevention of genital HSV is focused on behavioral and pharmacologic methods that reduce the risk of transmission to seronegative sex partners. Behavioral methods include condom use, disclosure of seropositive status, and avoidance of intercourse during outbreaks.1

In HIV-negative individuals with HSV-2 infection, once-daily valacyclovir suppressive therapy reduces the risk of transmission to serodiscordant heterosexual monogamous partners (number needed to treat [NNT] = 57 to prevent one infection over 8 months; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.27–0.99).10

Among HIV-positive individuals, suppressive therapy is not effective in preventing HSV-2 transmission. In one randomized controlled trial, daily acyclovir in HIV-positive patients did not reduce HSV-2 transmission to seronegative partners. However, patients in this trial were not taking antiretroviral therapy.11

Pericoital application of vaginal tenofovir gel reduces HSV-2 acquisition compared with placebo (NNT = 9 for women at 1 year; incidence rate ratio = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.30–0.77).12 However, this investigational therapy is not available for widespread use.

Efforts to prevent neonatal HSV infections focus on preventing maternal acquisition of genital herpes during late pregnancy, reducing viral shedding at the time of delivery, and avoiding neonatal exposure to active herpes lesions by offering elective cesarean delivery if lesions are present during active labor.1,13

In pregnant patients who have a known history of HSV infection, suppressive anti-viral therapy with acyclovir or valacyclovir starting at 36 weeks of gestation reduces asymptomatic shedding and symptomatic recurrence of HSV infection at the time of delivery.13 Suppressive therapy also reduces cesarean delivery for those with HSV infection, but evidence is insufficient to determine whether it prevents neonatal herpes.13

Patients with a first episode of symptomatic genital herpes during the third trimester may be offered a cesarean delivery due to the risk of prolonged viral shedding.14

There are no vaccines that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration or globally licensed for preventing the transmission or acquisition of HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection. Development of an HSV vaccine is a strategic priority for the World Health Organization and the National Institutes of Health.15,16

DIAGNOSIS

Although HSV is the most common cause of genital ulcers, the differential diagnosis should consider other conditions that cause genital ulcers, including chancroid, syphilis, mpox (monkeypox), granuloma inguinale, lymphogranuloma venereum, aphthous ulcers, Beçhet syndrome, drug reaction, psoriasis, cancers, and fungal or bacterial infections.1,17

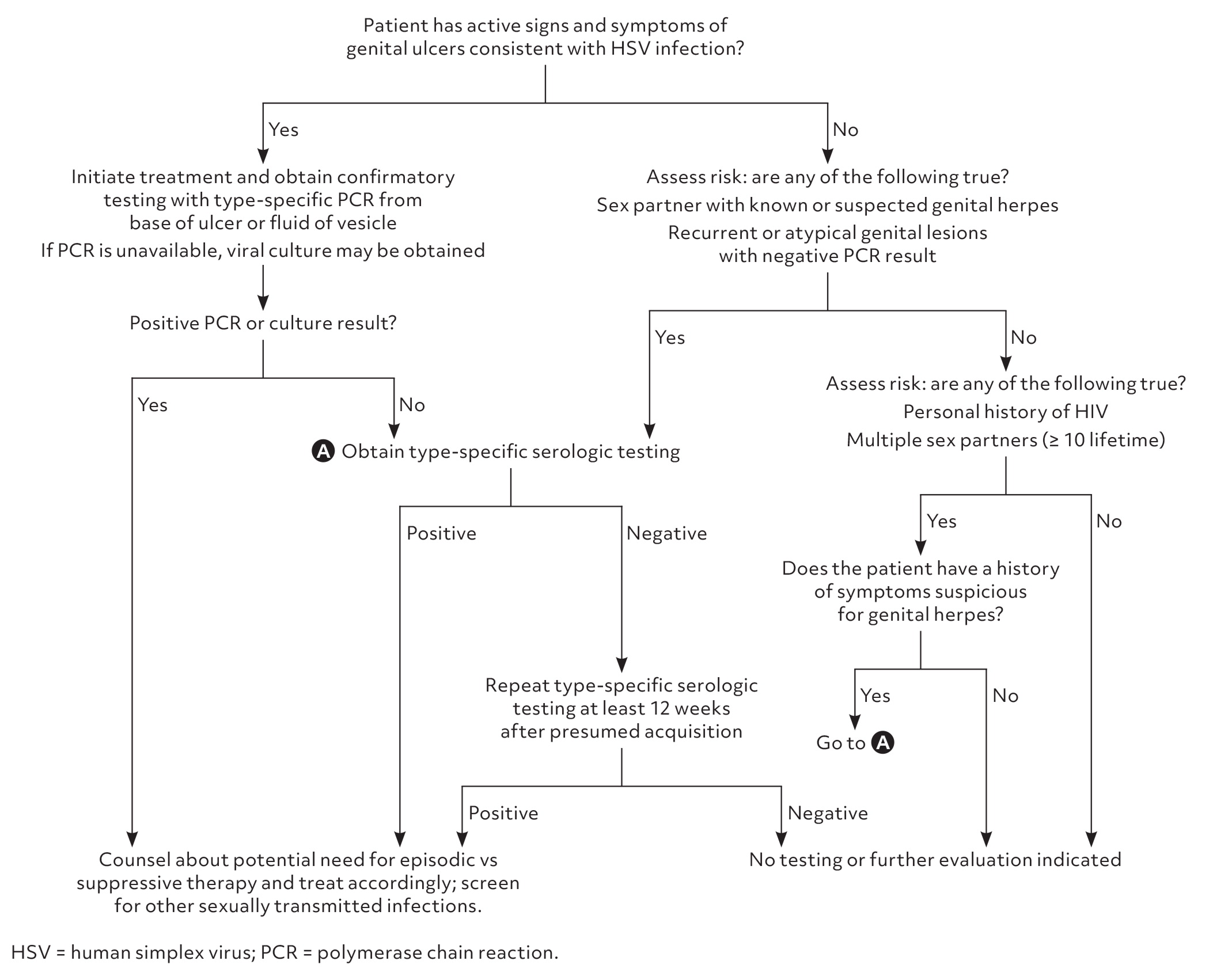

Figure 1 is a suggested approach to the evaluation of patients with clinically suspected genital herpes or who are at high risk for the disease.1,7,9

Signs and Symptoms

HSV typically appears as clusters of shallow, painful vesicles or ulcers on an erythematous base occurring on the genitals, rectum, or perineum.1

Associated symptoms may include fever, malaise, myalgias, dysuria, urinary retention, and tender inguinal lymphadenopathy.18

Mild primary infections may be unrecognized, making diagnosis and prevention difficult.19

Recurrent symptomatic episodes are typically less severe than primary outbreaks; however, a mild first episode does not reduce the risk of a severe recurring episode.19

Diagnostic Testing

The accuracy of diagnostic testing options is summarized in Table 2.20–22 [corrected]

Type-specific viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays of specimens collected from active ulcers or fluid from vesicles are highly sensitive and specific for HSV infection and are the preferred diagnostic tests.20 Viral culture of active lesions is much less sensitive than PCR but may be used if PCR is unavailable.1,21

Type-specific serologic testing for HSV-1 cannot distinguish between oral and genital infection and should not be used for diagnosis of HSV-1.1,8

The CDC recommends type-specific serologic testing for HSV-2 when there is a higher clinical suspicion for HSV-2. This may include patients who present with recurrent or atypical lesions, have lesions with negative PCR or culture results, have partners with known genital herpes, have HIV infection, and who present for STI evaluation, particularly those with more than 10 lifetime sex partners.1

Positive findings on a type-specific serologic test using enzyme immunoassay should be followed by confirmatory testing with Biokit or Western blot methods.1,22 False-negative serologic test results may occur during the early stages of infection; if genital herpes is suspected, repeat type-specific serologic testing can be performed at least 12 weeks after presumed acquisition.1

Individuals with suspected genital herpes should be screened for other STIs, including HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis.17 The risk of HIV is two to three times higher in people with HSV-2 infection (summary adjusted risk ratio = 2.7; 95% CI, 1.9–3.9) and among men who have sex with men (summary adjusted risk ratio = 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.4)6 In women, bacterial vaginosis and HSV-2 are the largest and most significant contributors to the risk of HIV acquisition, with a population-adjusted risk of 15% and 48%, respectively.23

| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive likelihood ratio | Negative likelihood ratio | Positive predictive value* (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA detection (polymerase chain reaction/nucleic acid amplification test)20 | 90.9–100 | 96–100 | 47 | 0.05 | 98 | 91.3 [corrected] |

| Viral culture21 | 18.6 | 97.5 | 6.3 | 0.84 | 86 | 46 |

| Enzyme immunoassay* 22 | ||||||

| HSV-1 | 70.2 | 91.6 | 8.8 | 0.33 | 90 | 25 |

| HSV-2 | 91.9 | 57.4 | 2.1 | 0.14 | 68 | 12 |

| Biokit or Western blot† (confirmatory)22 | ||||||

| HSV-1 | — | — | — | — | 91.7 | 70.0 |

| HSV-2 | — | — | — | — | 50.7 | 93.7 |

TREATMENT

Nucleoside analogue medications for HSV are used for episodic and suppressive therapy (Table 31,10). Treatment is indicated for symptomatic infections and all primary genital infections. Suppressive therapy is indicated for patients with frequent symptomatic recurrences.

Recurrences are less common with genital HSV-1 infection than HSV-2 infection; therefore, physicians should discuss suppressive therapy with patients who have genital ulcers due to HSV-1 infection.1,19,24

| Medication | Frequency and duration | Cost* |

|---|---|---|

| Initial episode† | ||

| Acyclovir, 400 mg‡ | 3 times daily for 7–10 days | $10 |

| Famciclovir, 250 mg | 3 times daily for 7–10 days | $15 |

| Valacyclovir, 1g | 2 times daily for 7–10 days | $10 to $15 |

| Recurrent episode | ||

| Acyclovir, 800 mg‡ | 2 times daily for 5 days or | $15 or $10 |

| 3 times daily for 2 days | ||

| Famciclovir, 500 mg and 250 mg | Single dose of 500 mg, followed by 250 mg 2 times daily for 2 more days | $5 |

| Famciclovir, 125 mg | 2 times daily for 5 days | $5 |

| Famciclovir, 1,000 mg | 2 times daily for 1 day | $5 |

| Valacyclovir, 500 mg | 2 times daily for 3 days | $5 |

| Valacyclovir, 1 g | Once daily for 5 days | $5 |

| Suppressive therapy | ||

| Acyclovir, 400 mg | 2 times daily | $10 |

| Famciclovir, 250 mg | 2 times daily | $30 |

| Valacyclovir, 500 mg§ | Once daily | $10 |

| Valacyclovir, 1 g | Once daily | $10 |

Drug Therapy

Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are first-line options for episodic and suppressive treatment of HSV. Acyclovir is the most widely available and least expensive medication for episodic treatment but generally requires more frequent dosing.1

Acyclovir or valacyclovir may be used for suppression during pregnancy.1,14

Topical antiviral medications are less effective for improving symptoms and should not be used.1

Complementary Medicine

Two bee products, honey and propolis (a resin-like material), may have antiviral properties and have been compared with acyclovir for treating painful herpetic lesions.24

Propolis ointment was more effective than acyclovir cream for healing painful herpetic lesions at 7 days (odds ratio = 4.7; 95% CI, 2.7–8.3; NNT = 8).25

In three randomized controlled trials, honey led to slightly faster healing of herpetic lesions than acyclovir (weighted mean difference = −1.88 days; 95% CI, −3.58 to −0.19) and was similar to acyclovir in reducing the duration of pain.25

However, propolis and honey are not currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Infectious Diseases Society of America for treating genital herpes.

Lifestyle and Behavioral Intervention

A pooled analysis found that consistent condom use (100% adherence) offers some protection against HSV-2 transmission in men and women (HR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40–0.94), although not to the same degree as for other STIs.26

Indications for Hospitalization

Patients with severe, disseminated HSV infection, including those with neurologic complications, should be admitted to the hospital and treated with intravenous acyclovir.1

Neurologic complications such as meningitis or encephalitis typically present as headache, fever, photophobia, confusion, or meningismus.27,28

Other forms of disseminated HSV infection include pneumonitis and hepatitis. Pregnant patients with disseminated HSV infection are more likely to present with hepatitis.29

PROGNOSIS

Genital herpes is a lifelong condition with no cure.30

Viral shedding from genital HSV-1 often wanes after the first year, but shedding from HSV-2 persists much longer and varies among individuals.24,31,32

Recommendations for lifelong management include disclosure to sex partners, use of condoms, and episodic or suppressive antiviral therapy to prevent recurrence and transmission.1,11

Data Sources: A search of PubMed, Essential Evidence Plus, and the Cochrane database was conducted. The key terms used were genital herpes, herpes simplex virus, herpes simplex-2, and neonatal herpes. Items included in this search were meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, clinical guidelines, and review articles. We critically reviewed studies that used patient categories such as race and/or gender but did not define how these categories were assigned, stating their limitations in the text when applicable. Search dates: June through November 2023 and September 2024.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force, US Department of Defense, or the US government.