New research suggests that the care of children has become less central to family medicine than it used to be, and some family physicians want to reverse the trend.

Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(7):45-52

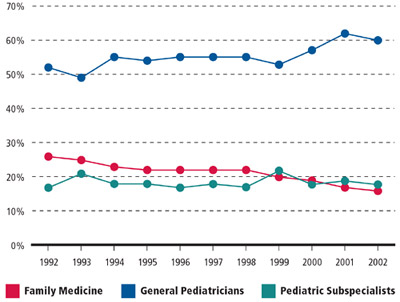

The share of children's health care provided by family physicians and general practitioners decreased by about 33 percent between 1992 and 2002, from one in four children's visits to one in six.1 This finding was at the heart of a report by the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care presented in June to the AAFP Task Force on the Care of Children. The report, which was based on a review of the literature as well as some new analysis of existing data, was commissioned by the task force to guide recommendations the group will make to the AAFP Board of Directors later this summer.

Robert L. Phillips, Jr., MD, MSPH, director of the Graham Center, says that primary data collection is needed to determine the root causes of the problem, but the center's report suggests several potential contributing factors.

“The biggest influence is probably that the number of pediatricians has grown so much, so fast,” Phillips says. “The pediatricians' work force has more than doubled over the last 25 years, and the birth rate is down 11 percent during the same period. The FP/GP work force has only grown about 60 percent during that time.”

The decline in the percentage of children's visits provided by family physicians and general practitioners corresponds with significant growth in the number of visits provided by general pediatricians and small increases in care provided by pediatric subspecialists and other physicians, according to the Graham Center research. (See the graph.) Market share has eroded most significantly in the care of children ages 5 to 13 (from 27 percent in 1992 to 15 percent in 2002). The proportion of care provided by family physicians and general practitioners to children of other ages has also dropped, from 22 percent to 13 percent for children 4 and under and from 30 percent to 21 percent for those age 14 to 17.1

The pediatrician work force is expected to keep growing. A 2004 study cited in the Graham Center report projected a significant oversupply of pediatricians “in all probable scenarios,” with the number of general pediatricians likely to increase 64 percent between 2000 and 2020 and the child population projected to expand only 9 percent.2

According to the Graham Center report, a lack of centralized data makes it hard to determine how many of the approximately 114,000 primary care nurse practitioners and physician assistants take care of children, but the number is likely to be at least as great as the number of general pediatricians, a fact that most workforce studies don't acknowledge.1

Competitive pressures aren't the only reason that family physicians' share of children's health care has declined. Family physicians who responded to the AAFP's 2005 Practice Profile Survey attributed the decline to other causes as well. Among the 36 percent of respondents who reported a decline in the number of visits they provide to children, these reasons were cited most frequently: they don't provide maternity care; hospitals and obstetricians lead families to use other specialists; the public does not perceive family physicians as providing health care to children; they don't provide newborn care in the hospital.

KEY POINTS

The proportion of children's health care being provided by family physicians has declined significantly since the early 1990s.

The number of pediatricians has grown dramatically in recent years.

Children in rural and underserved areas depend on family physicians more than ever for health care.

Mothers, babies and scope of practice

Graham Center researchers could not determine with available data whether family physicians' reductions in prenatal, obstetrical or newborn care have affected their role in caring for children. Definitive answers will require further study, Phillips says.

It does appear that fewer family physicians are taking care of pregnant women. According to a study cited in the Graham Center report, prenatal care by family physicians declined in all geographic regions of the U.S. between 1980 and 1999, from 17.3 percent of all prenatal visits to 10.2 percent.3

Phillips believes that the number of family physicians delivering babies and providing newborn care may be declining as well, but additional data is needed to confirm the trend.

“Based on what residents are telling us, there has been a shift in the last five to seven years out of newborn care. We're not clear why this is happening. A good number of family physicians and residency practices in particular are still providing a great deal of hospitalized newborn care for some very dependent populations like Medicaid and the uninsured, but family physicians are doing less of it overall,” Phillips says. Whether the shift is due to family physicians' opting out or being denied opportunities to take care of newborns is unknown, he says.

The relationship between taking care of newborns in the hospital and having a thriving child care practice hasn't been formally studied, but many see newborn care as a key to bringing kids into the practice. “Family physicians who don't have nursery privileges don't get new babies in their practices to the extent as those who are on ‘unclaimed’ newborn schedules or who take care of their existing patients' newborns,” says Perry S. Brown, Jr., MD. Brown is director of pediatric education at the Family Medicine Residency of Idaho in Boise.

PERCENTAGE OF CHILDREN'S OFFICE VISITS, BY SPECIALTY

The realities of hospital work

Family physicians are less likely than they were in the past to take care of sick children who are hospitalized, and this troubles some family physicians. “If the number of us who take care of our hospitalized patients continues to decline, it will be the deathblow for our specialty,” says Ed Hirsch, MD, a member of the AAFP Task Force on the Care of Children. Hirsch practiced full scope family medicine with obstetrics for 22 years in Illinois before recently taking a position as vice president of medical management with John Deere Health in Kingsport, Tenn. “If you're a parent, why in the world would you take your kid to a physician if you knew that when your kid got really sick and you needed that doctor more than ever, he or she wouldn't be there? If we don't take care of sick kids in the hospital, we may as well just do total ambulatory care and basically be midlevels.”

Brown says that in his experience patients frequently ask which hospitals their doctors admit patients to: “They want to know that they can see their physician when they're hospitalized.”

Hirsch and Brown both lament that growing numbers of otherwise willing residency graduates are leaving their residency programs feeling less than adequately prepared to take care of hospitalized children. “They are graduating residents who aren't as comfortable taking care of kids in the hospital as they should be,” says Hirsch. “You can't have eight residency faculty, none of whom do maternity care and only two of whom do intensive care types of work, and then expect the family physicians who train there to do full scope family medicine.” Increasing financial pressures have made it hard for residencies to offer salaries that are comparable to what most family physicians can earn in private practice, Hirsch says, which makes it hard to recruit experienced family physicians who have a full scope of practice.

Brown says changes in residency curriculum requirements may dilute family physicians' pediatrics experience. “It's not necessarily that they're spending less time doing pediatrics, although that is the case in some programs. It's that they're spending less time taking care of sick hospitalized kids. In the little over a year that I've been teaching, I've already seen our residents' experience diluted by changes in curriculum requirements. When you add something new to the curriculum, you have to cut something else. This is a problem for family physicians who want to take care of kids because, quite frankly, what helps you decide whether to take care of a certain segment of the population is the worst-case scenario you can envision and whether you're going to be comfortable taking care of patients in these scenarios.”

Other dynamics also make it difficult for family physicians to care for hospitalized children. In many cities with children's hospitals, family physicians have fewer and fewer opportunities to take care of sick kids, says Erica Swegler, MD, who practices in a family medicine group in the Fort Worth, Texas, area. “Sick kids are almost always referred to children's hospitals, or their parents elect to have them treated there. It doesn't make sense for me, geographically or economically, to maintain privileges at our children's hospital as well as at the two hospitals where most of my adult patients are admitted.”

Some family physicians have been excluded from the call service at their local hospital or take care of so few children who need to be admitted that they don't have enough volume to maintain admitting privileges. Others choose not to admit their own patients because they want to spend that time seeing patients in the office or they want to limit their work hours.

“I didn't know you take care of children!”

Family physicians aren't the only ones limiting their scope of practice in ways that may affect the number of children they take care of. The public and the media continue to have a narrow vision of what family physicians do. “One thing we learned as part of the Future of Family Medicine project is that we're not recognized by the public as the specialty that takes care of the whole family,” Phillips says.

And despite progress with the media (even “Dear Abby,” a long-time offender, suggested seeing a family physician in a recent column, Swegler says), media coverage remains a bone of contention for many family physicians.

“Family medicine is hurt so much by the absence of the mention of family physicians in tons of media,” Swegler says. Hirsch agrees: “Look at Redbook, Good Housekeeping, Ladies' Home Journal, and all the other so-called women's magazines. They all have columns about child care, and they always refer exclusively to pediatricians.”

Medical journals have made similar errors of omission. In May, JAMA published a patient education handout on childbirth that mentioned nurse midwives in addition to obstetricians but didn't mention family physicians.

“Public awareness continues to be a huge issue for the specialty. If only we could let them know that we exist, we could recoup some of that market share,” says Phillips.

Even existing patients aren't always aware of what their family physicians do. “We think it's fairly obvious,” says Swegler, who is also president of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, “but on a weekly basis, someone in my practice has the revelation, ‘I didn't know you take care of children.’”

More research needed

In addition to considering how factors such as public awareness and family physicians' attitudes toward inpatient care may have affected their role in the care of children, the AAFP task force explored some other hypotheses. One was whether the changes have been financially driven. The Graham Center report found no evidence to support that theory, says Phillips.

Primary research is needed in several areas where data is lacking, such as the importance that family physicians attach to this part of their practice and how malpractice rates and immunization hassles might influence the extent to which they take care of children, he says. “We just don't have data on these issues,” Phillips says. “Lots of questions remain about why this is happening.”

Unintended consequences

While the causes of family physicians providing less care to children still need to be untangled, the effects of the trend are somewhat clearer. One of the key findings in the Graham Center report is that a disproportionate share of children who live in rural and underserved locations depend on family physicians for health care, Phillips says. According to the report, family physicians' share of children's care in such areas hasn't eroded. Despite the fact that there are more general pediatricians than ever before, the percentage of recent pediatrics residency graduates choosing to practice in rural areas has fallen by half in recent years, and the percentage has dropped even more significantly in places designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas.4

Family physicians also take care of a disproportionate share of uninsured children and those with public insurance, according to the report. “We are the safety net for these children,” says Phillips. “The specialty has to be very purposeful about how we address this problem. We don't want to make any decisions that would serve to make it any harder for these children to get health care.”

Some believe the trend could put the specialty at risk as well. If family physicians relinquish their role as providers of children's health care, it will become even harder for the public to discern the difference between family physicians and general internists – or between family physicians and midlevel providers, who will undoubtedly pick up the market share that family physicians let go, says Hirsch. He also fears that the trend will have a detrimental effect on student interest in family medicine.

What the AAFP can do

The AAFP formed its Task Force on the Care of Children out of concern over these same issues and charged the task force with recommending how the specialty should address the problem. The task force is currently drafting recommendations.

Brown hopes the AAFP will continue the type of collaboration with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) that produced last year's joint release of an evidence-based clinical practice guideline on the treatment of acute otitis media.5 “This raises the profile of family physicians and helps people to better understand that family physicians take care of kids and do it well,” he says.

Relations between the two organizations could be complicated by predictions of an oversupply of pediatricians. “Projections of a workforce surplus have led some to suggest that pediatricians ought to expand the services they offer, including young adult care, and compete for a greater share of the children currently cared for by non-pediatricians, including family physicians,” Phillips says.

But Phillips is optimistic about opportunities for the two organizations to collaborate. “We should look more carefully at practice models that include both pediatricians and family physicians,” he says. “This would help the pediatricians with the challenges they have related to taking care of families, and it would help us in terms of bringing kids into the practice and legitimizing our role in children's health care.” The pediatrics community recognizes these issues, noting in its 2000 report The Future of Pediatrics Education that there will be new opportunities to implement cooperative models, particularly in underserved areas.6

Family physicians would also benefit from the AAFP and other family medicine organizations getting more involved in national public policy and advocacy for children's health issues, Brown says. “The AAP has been very strong in this area, and the AAFP should be as well.”

Family medicine residency programs also have a key role to play in better equipping family physicians to take care of children, Brown says. He hopes programs will protect and strengthen the relevant parts of the curriculum, particularly the focus on taking care of hospitalized kids.

Another strategy that some family physicians hope the AAFP will employ is to promote the specialty, and the fact that family physicians take care of kids, more aggressively.

What you can do

Regardless of what transpires on the national landscape, individual family physicians who want to take care of kids can do a lot to increase their opportunities. Maintaining the fullest scope of practice you can is a good start, of course. The physicians interviewed for this article shared the following additional suggestions:

Build better relationships with ob/gyns and pediatricians in your community. Brown advises new residency graduates to go to the first ob/gyn department meeting at the hospitals where they'll be seeing patients. “I tell them to introduce themselves, and let the ob/gyns know they have experience with and are enthusiastic about taking care of newborns,” he says. Of course this will be an easier sell for family physicians who don't deliver babies.

Swegler also suggests having a similar conversation with ob/gyns and their office managers about the forms they give to pregnant women and the discussions they have with patients about newborn care options. “They all have information sheets that list doctors who provide newborn care. Make sure that it doesn't include just pediatricians. And if you don't deliver babies, don't hesitate to mention that when you refer pregnant patients to them your expectation is that the mother and the baby will be sent back to you,” Swegler says.

Heighten your visibility in the hospital. Family physicians need to attend hospital staff meetings and have a representative on the ob/gyn and pediatrics committees, says Swegler. “These groups can make decisions that significantly affect your ability to practice in the nursery or the hospital, so you need to know what's going on and be part of the discussion.”

Get to know the nurses in labor and delivery and the nursery. At one of the hospitals where Swegler sees patients, the department of family medicine succeeded in getting the registration forms for newborns changed to refer to “doctor” instead of “pediatrician.”

Brown advises family physicians to sit down with the head nurses in labor and delivery and the nursery. “You have to do it in a sensitive way,” he says. “Ask them how they approach asking the mother who the baby's doctor will be. If you're concerned by what you hear, tell them how it might be interpreted. Ask if they would consider taking a different approach, and describe what you have in mind.”

Don't rely solely on word-of-mouth marketing. Many family physicians know that word-of-mouth is their best marketing tool, and they believe they don't have the expertise or the money for more active marketing efforts. But be sure you've considered all the options, even non-traditional ones. Swegler's group of five family physicians is launching its first-ever ad campaign this summer with an ad that will be part of the pre-show advertisements at local movie theaters. The ad includes a photo of the physicians and lists the services they provide, and costs about $2,000 a month. Increasing competition in their area motivated them to try it, and they were encouraged by the success that a women's health care group in their area had with a similar ad.

Swegler also recently persuaded one of her local hospitals to publish a full-page article on family medicine in the magazine it distributes to area residents. The article described the services that family physicians provide and listed the names of all the family physicians who are on staff at the hospital. It also mentioned a recent study that showed a higher ratio of primary care physicians to population results in lower mortality rates overall and for heart disease and cancer specifically.7 “I can't buy this kind of publicity,” she says.

Don't overestimate your existing patients' understanding of what you do. “You have to be vigilant and take every opportunity to talk with your patients about your scope of practice,” Swegler says. Visual reminders can be effective as well. In his practice in the Baltimore area, Jeff Schultz, MD, has posted a sign on the checkout counter that reminds patients that he takes care of the entire family. Hirsch says the best marketing tool he has used is to cover the walls of his exam rooms with photos of newborn babies he delivered.

“It was amazing how many people would be waiting and looking at those pictures and would say they didn't know I delivered babies or took care of kids,” he says. He routinely asked families to send him a copy of their newborns' photos, and says they were enthusiastic about doing it.

Talk with patients whose children might be outgrowing their pediatrician's office about transferring. Most pediatrics offices are geared toward taking care of infants and younger children, and most adolescents start feeling uncomfortable with it at some point, Swegler says, especially young males who have to see female pediatricians for sports physicals. As you see patients who you know have adolescent-age children seeing pediatricians, don't hesitate to mention your interest in taking care of the children when the parents decide it's time to move on.

Create a kid-friendly environment. Make sure your practice looks like a place that takes care of kids. Some ideas include having the requisite toys, books and furniture for kids in the waiting room, a treasure chest with inexpensive toys that kids can choose from to take home and kids' books in each exam room. Having an annex for well children is a good idea if you have the space, Brown suggests. A colleague of his has decorated his exam room with pictures drawn for him by kids in his practice.

Make sure your hours and appointment access are sensitive to the needs of young families in your community. Schultz says his office is “open practically all the time, and that probably makes a difference in the number of children we have in the practice.” He and the two PAs he works with offer extended hours three evenings a week and on Saturday morning. In Maryland, PAs can practice with phone access to a supervising physician, so Schultz's PAs work most of the extra hours without him having to be in the office. He has a part-time front-desk person who covers the evening and Saturday shifts as a second job.

“The type of scheduling you do is critical,” Brown says. “In my experience, some degree of same-day scheduling leads to happier parents and better-taken-care-of kids.” When Brown was in private practice, he set aside several appointments in the mornings and afternoons and instructed his office staff to hold them open for same-day, usually sick, visits.

Offering early morning walk-in clinics is a popular strategy for pediatrics groups in some areas. Brown says whether family physicians should emulate these or other approaches depends on the community they practice in. “If you're living in a sizable community that has lots of pediatrics groups and they're all doing it, you probably have to match them,” he says. “If that's not your situation, then you have the option, and doing it would probably give you a marketing advantage.”

Learn to code a preventive medicine visit in combination with a problem-oriented service, and code immunizations fully. Make sure you're not losing revenue on kids' visits, which can be complicated to code for a couple of different reasons. Proper use of modifier −25 is the key to getting paid for a problem-oriented visit that arises in the context of a well-child visit. (See “Making Sense of Preventive Medicine Coding,” FPM, April 2004.) And you can't afford to lose money on immunizations. You should be billing for the immunization administration in addition to the vaccine itself. CPT 2005 includes new codes (90465–90468) for immunization administration that can be used when you treat a patient under 8 years old and counsel the patient or the patient's family. In cases where it is not appropriate to use one of these new codes, you should be using the appropriate administration code in the 90471 to 90474 series.

Take nothing for granted

The Graham Center report demonstrates that family physicians should not take for granted that the future of family medicine will include the care of children. The AAFP will play a key role in ensuring that the scope of family medicine continues to include taking care of children. You can do your part by considering the consequences of your decisions to limit hospital work, educating your patients and your community about your scope of practice, and employing other strategies described in this article. Your specialty, your practice and the families that value your care will be better for it.