To describe the current phenomenon, we need a better term that puts the blame where it belongs and reminds us that the problem is responsive to multiple treatment strategies.

Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(5):4-7

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

Physician burnout is an epidemic that affects approximately 44 percent of physicians.1 For family doctors, the situation is worse: A recent study found that in 2017 more than half of family physicians reported burnout.2 Although this was an improvement from 2014, the incidence of burnout was still unacceptably high. This same study indicated that just 28 percent of the general U.S. working population reported burnout. This implies that, compared with the general population, family physicians face additional factors. Burnout increases medical errors and reduces patient satisfaction, which makes it everyone's problem.3 Some have labeled it a public health crisis.4

THE PROBLEM WITH “BURNOUT”

To many physicians, the word burnout implies that the problem stems from personal weakness when, in fact, the problem is much more systemic. Physician burnout is not caused by a personal lack of grit and resilience. Doctors are accustomed to academic rigor, long hours of often stressful work, and many sleepless nights. They excelled in college, mastered medical school, and then spent a minimum of three years in residency. Physicians are the opposite of wimps — they are committed, hard-working people with a deep sense of altruism and proven resilience. Our health care system, on the other hand, is broken: It is configured around and constrained by warped financial incentives, which often conflict with patient-centric values.5 It is hampered by many areas of inefficiency.

In the search for a better and more accurate term than “burnout,” recent articles and video blogs have suggested “moral injury.”6 Moral injury is lasting distress resulting from “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations,”7 the type of distress sometimes seen among war veterans. Health care system-induced moral injury should not be directly compared to the type of moral injury inflicted on the battlefield. However, when physicians feel the health care system leaves them unable to practice medicine in a way that aligns with their ethics, it is frustrating and demoralizing. Physician moral injury can be one of many contributing factors to what is commonly labeled burnout.

A BETTER TERM FOCUSED ON THE REAL PROBLEM

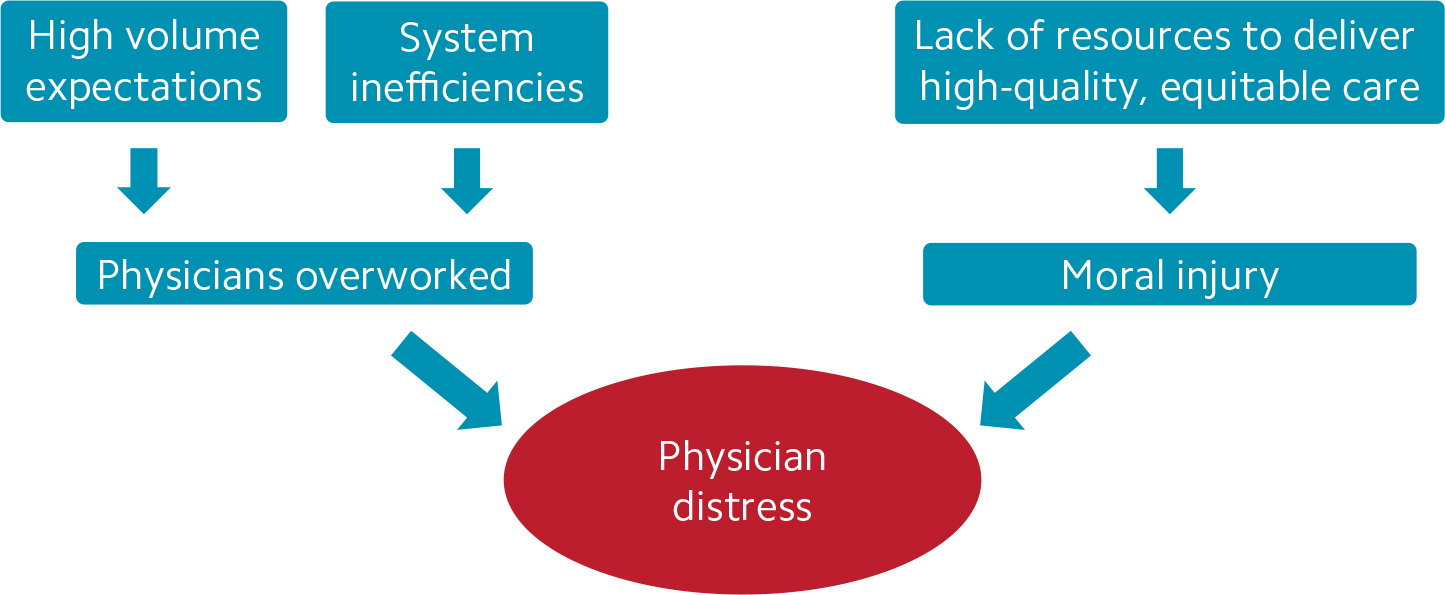

Although physicians can be affected by moral injury, many doctors primarily feel overwhelmed by the daily quantity of work that confronts them — particularly paperwork and computer work. Keeping up with this high workload reduces time for family, friends, and hobbies. The current health care system, with its multiple inefficiencies, wears physicians down, drains their energy, and makes it harder for them to connect with their patients. (See “How the health care system causes physician distress.”)

To describe the current phenomenon, we need another term: system-induced distress responsive to multilevel strategies (SDRMS). This term not only puts the blame where it belongs but also acknowledges that the problem is responsive to multiple treatment strategies. SDRMS avoids the emphasis on physician weakness and at the same time encourages an internal locus of control. Rather than placing physicians in the role of passive victims futilely hoping that others will miraculously fix a flawed system, SDRMS empowers physicians to become active participants and points to a framework for positive change. Virtually all physicians have some level of system-induced distress and can use this framework to make a difference for themselves and their colleagues.

A FRAMEWORK FOR REMEDYING SDRMS

The biopsychosocial model is a distinguishing characteristic of family medicine. When a patient presents with migraines, diabetes, and depression, family physicians often recommend insulin and other medications, dietary and exercise changes, as well as counseling. We are trained to attack a patient's issues with every tool in our toolkit. In the same holistic fashion, we need to use every available tool to treat SDRMS, attacking it from multiple angles at the same time.

The American Academy of Family Physicians describes the “family physician ecosystem” as comprising five components — the health care system, organization, practice, individual, and physician culture — and its Physician Health First portal is organized around this framework. The best approach to remedying SDRMS is to simultaneously address it on each of these levels.

At the health care system level, steps must be taken to reduce physicians' paperwork and computer work (such as prior authorizations), diminish the documentation burden, and ensure fair compensation rules. Additionally, policies must be implemented to bring us closer to efficient health care coverage for all, making treatments available to more patients and reducing the frustration physicians feel when they are unable to effectively help patients because of socioeconomic concerns. This will help reduce moral injury. Physicians who practice in settings with higher levels of social support services for patients are less likely to report burnout.8

At the organizational level, leaders must be more responsive to the ideas and suggestions of the doctors and other staff who are working in the trenches. Organizations should help physicians develop the leadership skills needed to lead changes in the health care system, and more physicians should seek leadership roles. Working physicians need to address those in leadership positions in positive, constructive ways and with specific suggestions. Rather than wasting physician time on tasks that do not require our specific expertise, organizations should maximize physician time as a valued resource.

At the practice level, there are multiple ways to maximize teamwork and make practices more efficient, including approaches to team documentation.9–10 Physicians can also access practice improvement strategies at the American Medical Association's StepsForward.org, share efficiency recommendations with colleagues, and pursue continuing education focused on practice efficiency.

At the individual level, we cannot be bystanders hoping someone else will improve the health care work environment. Each of us must address the public health crisis of SDRMS by finding ways to influence and effect the changes necessary for meaningful improvement. Additionally, although SDRMS is not caused by individual weakness, it is important to maximize individual health and strength. Even at its best, medicine is inherently stressful. Just as world-class athletes benefit from ongoing training, every physician can benefit from an in-depth understanding and practice of stress management techniques that include mindfulness, reframing, and gratitude.11–12 Learning and practicing these techniques not only helps us as physicians but also empowers us to effectively share these same strategies with our stressed patients.13 Effective stress-management strategies allow us to care for both ourselves and our patients in a more effective and holistic manner.

At the level of physician culture, we must address our own expectations. Doctors tend to be hard on themselves and, traditionally, have been trained with an individualistic mind-set — expecting perfection and rarely seeking personal help. We must be compassionate not only with our patients but also with ourselves, our colleagues, our staff, as well as our residents and students. We must be open to relying on our teams for strength and support. We must regularly see our own primary care physicians for care and be more willing to seek counseling. Seeking help should not be viewed as a sign of weakness but rather a sign of strength, wisdom, and professional maturity. Some of the very best physicians are those who have suffered, sought help, and gotten better. Those physicians have a profound empathy that helps them better relate to and care for their suffering patients. As a physician, your well-being is crucial to your patients' health and your longevity as a caregiver. Don't wait until you're at wit's end to ask for help and guidance — seek it early and often. And for some, particularly physicians in private practice, medicine can feel isolated, so seek regular support from peers.14

A CALL TO ACTION

Physicians, along with other types of health care workers, must address SDRMS on every level and actively work to aggressively, extensively, and quickly change the health care system. Every step of the way, those involved in clinical practice must become intimately involved with the transformation of the health care system and organizations. If, instead, we only offer vague complaints without specific recommendations, nonclinicians may very well implement a cure that will be worse than the disease. We can't afford to be bystanders in the midst of this public health crisis.

The words we use to describe a situation are important because they change the way we understand and approach it. However, terminology is nothing without action. Medicine is a profound and noble calling. Together, we must create an environment in which the vast majority of physicians are fulfilled in their practices and the conversation can change from “system-induced distress” to “system-enhanced thriving” in practice and in life.