Learn how to implement an integrated behavioral health program that will more than pay for itself while increasing patients' access to care.

Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(6):11-16

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

Family physicians understand that integrating behavioral health with primary care improves outcomes in both mental and physical health. More than a dozen well-designed studies support that. In January 2017, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) rolled out new payment opportunities for primary care physicians and clinicians who integrate behavioral health into their practices. The four billable procedure codes are for two different levels of behavioral health care. The more basic service is called general behavioral health integration, or BHI, and can potentially be delivered by a physician alone (see “General behavioral health integration model”). The more comprehensive service, the psychiatric collaborative care model (CoCM), requires a primary care (or other) physician or clinician to lead a team that includes a behavioral health care manager who checks in with patients at least once a month and an off-site psychiatric consultant who regularly reviews patients' progress and offers advice. This article will discuss how we implemented the CoCM model in our practice. It will also provide guidance on how you can establish a similar program to improve patients' access to behavioral health care while increasing revenue.

KEY POINTS

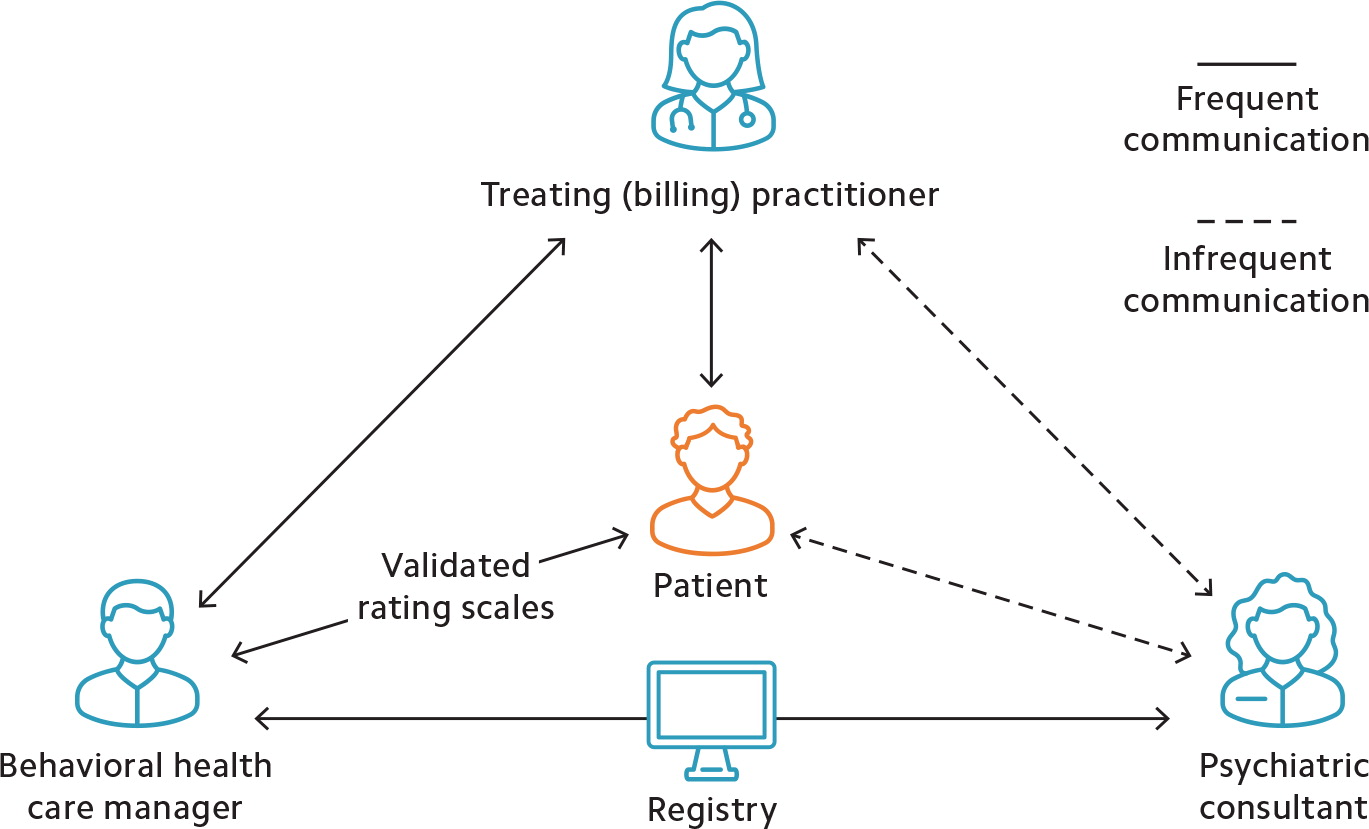

The psychiatric collaborative care model (CoCM) is an integrated behavioral health services program that includes a primary care physician or other clinician, a behavioral health care manager, and a psychiatric consultant.

CoCM can be billed to Medicare using procedure codes 99492, 99493, and 99494, along with the appropriate ICD-10 codes for the conditions being treated.

Patients can be referred for CoCM for any behavioral health condition the primary care clinician feels would benefit from it.

GENERAL BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION MODEL

Medicare also covers general behavioral health integration (BHI), which is more basic and easier to fit into an existing chronic care management program than the psychiatric collaborative care model (CoCM). BHI can be provided by the physician or clinician alone or can include a behavioral health care manager (specialized training is not required for the behavioral health care manager in the BHI model). A psychiatric consultant is not necessary. The BHI model requires a minimum of 20 minutes per month checking on each enrolled patient, versus the 60 minutes required for CoCM. To bill for BHI, use code 99484, which pays $48.65 per month through Medicare, according to the 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (nonfacility national payment). Rural health clinics and federally qualified health centers must use different codes for BHI and CoCM. The University of Washington has developed a coding “cheat sheet” for those facilities.

HOW COLLABORATIVE CARE WORKS IN OUR SMALL-TOWN PRACTICE

Our clinic is a small, rural practice in the Florida panhandle that is isolated geographically from psychiatric services. It's about one hour from the nearest psychiatrist. There are limited counseling services in our community, and none are available to Medicare patients.

We have long seen the need for behavioral health integration in our practice because of these access issues. Years ago, we found it useful to bring counselors in-house because patients were more likely to return for counseling when we provided a “warm handoff” by introducing patients to the counselor upon referral. But Medicare patients still lacked access, which is the case in many communities, because Medicare doesn't cover services performed by licensed professional counselors. This made the CMS integrated behavioral health program very enticing.

We knew that we could not support a full-time counselor, at least not in the beginning. We considered providing only the general BHI service, but instead decided to look for part-time team members who could help us offer the more comprehensive CoCM service because it provides more intense help for our patients, with more time for face-to-face counseling. It also provides much higher reimbursement.

We were fortunate to find a semiretired psychiatric nurse practitioner and a master's level mental health counselor, which allowed us to implement the full CoCM program (after our counselor moved we replaced her with a licensed practical nurse who has experience and training in behavioral health). There may be potential team members in your community who could help you do the same. You can contract with these individuals and pay them on a per-patient basis instead of making them your employees, until you have a patient load that would support an employed mental health professional.

The following will explain what each person does to meet the CMS billing requirements for CoCM (see “Psychiatric collaborative care model team interaction”).

The billing practitioner (team leader). Under CMS rules the team leader can be a physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, clinical nurse specialist, or certified nurse midwife. The team leader's duties are to oversee the program, identify patients appropriate for CoCM, and prescribe behavioral health medications as needed.

The behavioral health care manager (team “worker bee”). The behavioral health care manager works under the oversight and license of the billing practitioner. For the CoCM model, CMS requires the care manager to have formal education or specialized training in behavioral health (such as psychology, social work, or nursing). But CMS does not specify a minimum education requirement or licensure requirement and does not mandate that the individual meet all the requirements to independently provide and report services to Medicare. The care manager's duties include participating in an initial psychosocial evaluation by the primary care team, followed by monthly (or more frequent) interactions with the patient to monitor for medication adherence and side effects. The care manager tracks patient improvement using validated rating scales and communicates with both the psychiatric consultant and the billing practitioner. According to CMS, care managers may also provide basic, evidence-based behavioral interventions in line with their training. The care manager must be available to patients outside of normal clinic hours, as needed.

The psychiatric consultant (team adviser). This team member must be a medical professional trained in psychiatry and qualified to prescribe the full range of behavioral health medications. The psychiatric consultant can be a psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner and does not have to be qualified to bill Medicare independently. This person advises the team on each patient enrolled in the program and makes recommendations regarding diagnoses and medication management, primarily when patients are not improving as expected or when they experience difficult-to-manage medication side effects. The psychiatric consultant usually does not meet patients face-to-face. In our practice, the billing practitioner makes the final decisions on aspects of care such as medication changes and assumes liability for them as the team leader. But team members should clarify responsibilities with each other up front and consult with their insurers about any liability questions.

The patient/beneficiary (team purpose). It is important not to forget that patients are a vital part of this team. They are expected to participate in their care and to assist in the self-management of their illness. One of the primary goals of this program is to equip them to better manage their behavioral health, and their input in their care plan is invaluable.

WORKFLOW

Once formed, the CoCM team embarks on a multistep process to identify patients for the program, perform initial tasks to establish patients' behavioral health needs, and check in with the patients regularly. The workflow generally goes like this:

Referral. Patients are referred by the family physician or other billing practitioner when they are recognized as appropriate for CoCM. This may occur during routine office visits or through depression screenings during annual wellness visits. Other members of your clinic staff may also recommend patients for CoCM. Patients are considered appropriate if they have been diagnosed with any behavioral health condition the billing practitioner thinks could benefit from CoCM. In our clinic, we refer patients with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, substance use disorders, grief reactions, adjustment disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other conditions.

Consent. The family physician or other billing practitioner explains the CoCM program to the patients and obtains their consent to be enrolled. Under CMS rules consent may be verbal or written, but it must be documented in the patient's chart. Consent should include permission to discuss the patient's case with all team members, including the psychiatric consultant. It should also include notifying patients of copays. Medicare Part B coinsurance applies for CoCM, but is covered by most Medigap and Medicaid plans.

Warm handoff. This is not a CMS requirement, but it is a very good idea if your behavioral health care manager is in your clinic. A warm handoff involves introducing patients to the care manager before they leave the clinic on the day they are referred. This allows them to become comfortable with the person with whom they are going to be discussing their behavioral health issues. We find that when this occurs patients are more likely to return for their initial appointment with the care manager and to successfully enroll in the program.

Initial psychosocial evaluation. CMS requires the care manager to spend at least 70 minutes completing several tasks during the patient's first month in the program. The first is a comprehensive psychosocial evaluation that includes family history, eating and sleeping patterns, substance use history, past and present mental health history, use of psychotropic medications, abuse or trauma history, and a history of the conditions for which the patient was referred.

Administration of validated rating scales. The care manager provides a benchmark of the patient's condition using any rating scale that is appropriate for the diagnosis for which the patient is being seen. Examples include PHQ-9 for depression and GAD-7 for general anxiety disorder.

Creation of a care plan. The care manager and the patient form a care plan that will be reviewed by the rest of the team. Our care plan includes the diagnoses being treated, the patient's behavioral health medications, any special psychosocial needs, and related problems such as sleep disturbances or weight issues. It also outlines what behavioral therapies we will be using. This is a fluid plan for the patient's success. It should be revised as needed.

Entry into a registry. A disease registry is a tool for tracking the clinical care and outcomes of a defined patient population. We use a tracking device that is built into our electronic health record (EHR) and graphs PHQ-9, GAD-7, and other scores. A paper or electronic spreadsheet could be used instead. Sample registries are available online, including a comprehensive one that can be downloaded from the University of Washington's Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center (see “Resources”).

Initial psychiatric consultant review. Also within the first month, the care manager discusses the patient's care with the psychiatric consultant and relays any recommendations to the billing practitioner. Recommendations usually involve fine-tuning diagnoses, adjusting medications, and managing side effects.

Regular check-ins. The team checks in with the patient regularly, discussing things like medication adherence and side effects. After the first month, the care manager spends at least 60 minutes per month on each patient. That time could include counseling, administering rating scales, and recording progress or setbacks. The care manager may also provide brief interventions such as behavioral activation or motivational interviewing and record them in the registry. The primary care team also regularly reviews treatment plans and patient progress with the psychiatric consultant. These reviews should happen at least once a week, according to CMS, but they could be more frequent if the patient's health is not improving as expected. The entire team should review each patient's progress and develop relapse prevention plans. The team can also weigh in on whether the patient should be referred for more intensive behavioral health care, but that decision ultimately lies with the team leader.

Bill at the end of the month for the services provided. Use the ICD-10 codes for the conditions being treated along with the appropriate procedure codes for the services that were provided that month (see “Coding for psychiatric collaborative care”).

CODING FOR PSYCHIATRIC COLLABORATIVE CARE

The following codes are billable monthly and should be submitted with the ICD-10 codes for the diagnoses being treated. The University of Washington also has a coding “cheat sheet” available.

| Codes | Description | Payment* |

|---|---|---|

| 99492 | Initial Collaborative Care Management, paid for the first 70 minutes of care manager time (30 minutes assumed billing practitioner time). | $162.18 |

| 99493 | Subsequent Collaborative Care Management, paid monthly for the first 60 minutes of care manager time (26 minutes assumed billing practitioner time). | $129.38 |

| 99494 | Each additional 30 minutes of care manager time (13 minutes assumed billing practitioner time). Billed separately as an add-on code to either 99492 or 99493. Maximum of two add-ons per month, per patient. | $67.03 |

This program not only enhances patient care and improves outcomes, it can also be financially rewarding. Assuming a caseload of 20 patients and the contracted rates we pay our behavioral health care manager and psychiatric consultant, our net profit is almost $1,400 per month (see “Financial breakdown”).

But the greatest value of our CoCM program is the professional satisfaction of knowing that we are providing behavioral health care close to home for patients who otherwise would not be able to access it.

One final rewarding aspect is how much we have learned from each other. As a family physician, I (Dr. Bailey) feel confident treating most mental health conditions, but I have learned a lot about pushing meds to higher doses and adding low doses of mood stabilizers for patients with difficult-to-manage conditions. Our behavioral health care manager's training emphasized counseling, but seeing patients improve on medications has given her a new appreciation for medication management. Meanwhile, I have gained a new appreciation for the benefits of counseling. We have all learned much from our patients, who have impressed us with their motivation to improve their health and overcome trauma and tragedies that would never have been revealed to us if it were not for the comprehensive treatment that this program provides.

FINANCIAL BREAKDOWN

Below is a breakdown of Bailey Family Practice's psychiatric collaborative care model (CoCM) profit margin, assuming a caseload of 20 patients. The contract rates listed reflect what our practice has been paying its behavioral health care manager and psychiatric consultant and may vary depending on what type of professionals you hire. For example, our consultant is a psychiatric advanced practice registered nurse, while most psychiatrists would charge higher hourly rates. New patient evaluations and patients who were seen for more than 60 minutes in a month increase the profits, because Medicare pays more for those than our care manager charges.

| Monthly cost | ||

| Behavioral health care manager | $50 per patient × 20 patients | −$1,000 |

| Psychiatric consultant | $10 per patient (or $100 per hour, whichever is greater) × 20 patients | −$200 |

| Monthly revenue | ||

| Medicare payments | $129.38 per patient* × 20 patients | +$2,588 |

| Monthly profit | ||

| Net revenue | +$1,388 | |

RESOURCES

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services requirements and educational resources

University of Washington Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center training resources and tools