Physicians increasingly must lead change in their practices, which requires a basic understanding of the project management process and common tools.

Fam Pract Manag. 2023;30(5):19-24

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

Imagine your clinic would like to improve its routine lipid screening metrics. To address this, you are tasked with leading implementation of a point-of-care (POC) lipid testing device, as an alternative to sending patients to the contracted phlebotomy lab. How would you proceed?

With health care constantly evolving, physicians are frequently asked to take part in or lead projects that are necessary for progress. For busy physicians, this may feel like a daunting task, but by virtue of practicing medicine, you have already developed many of the skills required for effectively managing a project — including planning, communicating, assessing risks and benefits, facilitating change management, and appealing to many stakeholders. While you use these skills differently in the context of an exam room, you can apply them to project management, whether you are leading a large-scale effort, implementing a quality improvement project for maintenance of certification, or simply participating as a stakeholder.

KEY POINTS

Following the five-phased, systematic approach to project management protects against missed steps and helps ensure project success.

During the planning phase, several tools can help you define critical tasks and subtasks, understand the flow of tasks and their dependencies, and get a high-level view of task and project duration.

In parallel with the project execution phase, the monitoring phase involves tracking progress on different aspects of the project such as timeliness, budget, quality, or effectiveness.

WHAT IS PROJECT MANAGEMENT, AND WHY DO WE NEED IT?

Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to support a change effort that has a finite scope and end point.1 It provides a systematic approach with five distinct phases, discussed below. Following the methodology protects against missed steps, which can prove costly, and helps ensure project success, meaning the end result is delivered on time, on budget, and on target (with all promised features and functions).2

An estimated 36% of projects succeed, 19% of projects fail, and 45% are “challenged,” meaning they meet at least one success criteria but not all.2 Common reasons for failure include poor estimates/missed deadlines, lack of executive sponsorship, poorly defined goals and objectives, changes in scope mid-project, insufficient resources, and poor communication.3 Projects that follow proven project management strategies are 2.5 times more likely to succeed, according to one analysis.4

PHASE 1: INITIATION

The purpose of the initiation phase is to define the project (the big picture) and get authorization to move forward. Typically, this phase is led by a project sponsor, someone who is championing the project. Two documents can help with this.

The business case. This document justifies the need for the project and describes the following:

Problem or opportunity (e.g., “We have a low rate of conversion for pending lipid orders into lab results. Comparable local outpatient clinics that have implemented a point-of-care lipid testing device have seen improvements of X percent in their conversion rates”),

Purpose (e.g., “We aim to increase routine lipid screening metrics by implementing a point-of-care lipid testing device”),

Benefits/value added for key stakeholders (e.g., “For patients, this will streamline and improve care delivery and increase satisfaction; for clinicians, it will allow face-to-face counseling for results and decrease outside administrative requirements; for the clinic, it will potentially increase revenue”),

Feasibility, costs, and risks (e.g., “Start-up costs are approximately $X; ongoing maintenance costs are $Y; and the anticipated revenue is $Z. We would see a profit by the fourth quarter of this year. Lack of coverage by some insurers and ongoing staffing challenges could affect success if not addressed”).

The project manager or sponsor should present the business case to key stakeholders for input and then to a funding committee or other decision-maker for approval. If the project is greenlighted, the project manager creates a project charter.

The project charter. This document provides a high-level overview of the project and can borrow elements from the business case you've already prepared. It should describe the following:

Scope of the project (what's in and what's out),

Proposed timeline with anticipated milestones,

Key performance indicators/measures of success,

Estimated costs,

Threats and opportunities.

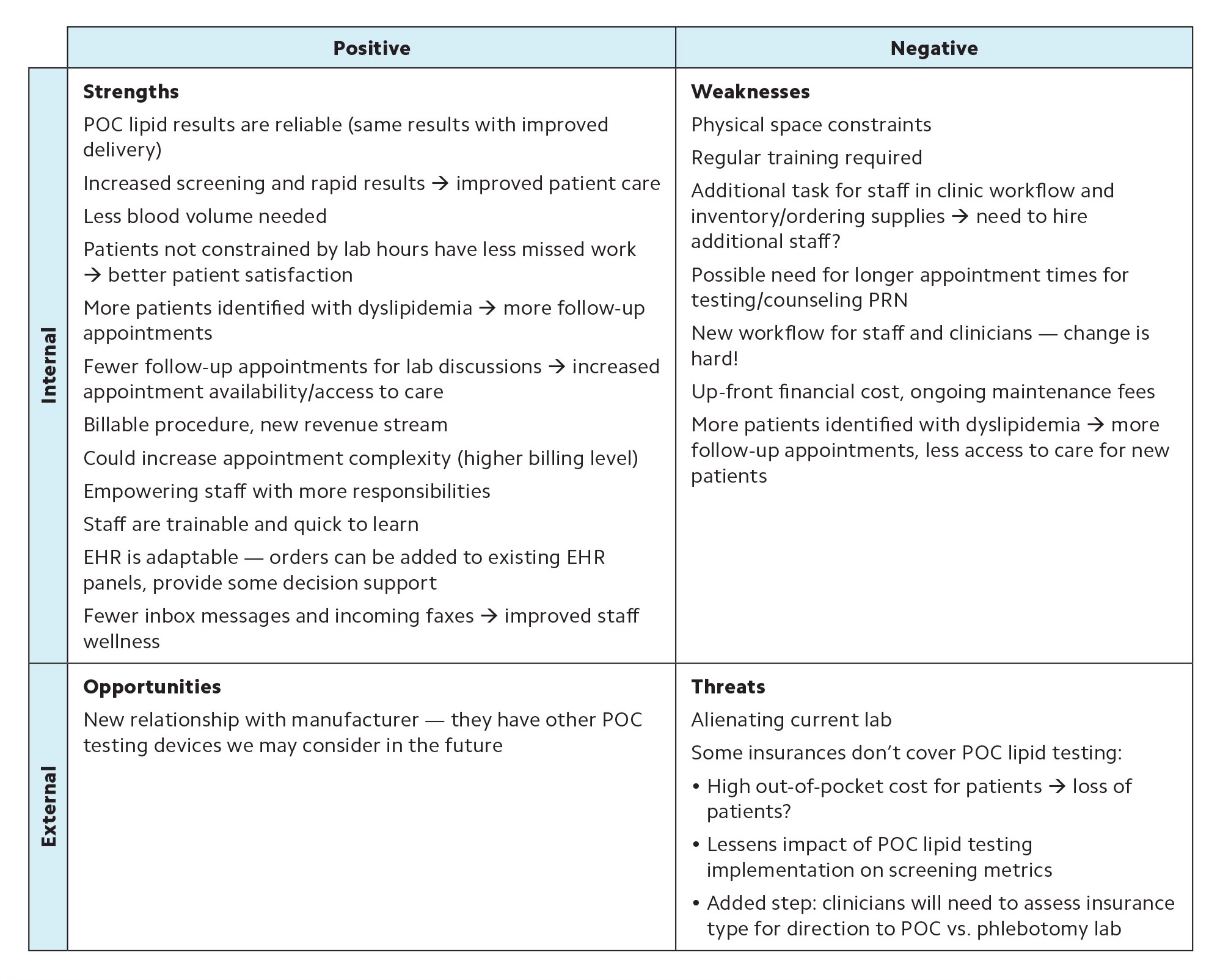

For this last item, completing a “SWOT analysis” of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats can help you identify key issues you'll need to address or leverage later in the project. Using our clinic scenario as an example, you may identify that some insurers do not cover the point-of-care test, so physicians will have to identify patient insurance at the point of order entry, which creates a burden that your team will need to acknowledge and eventually solve for.

The charter should name the project manager, those on the team, and the project sponsor. Once the project charter is approved, any changes (such as expanding the project's scope) should require a stringent documentation and approval process so the success of the project is not jeopardized.

SWOT ANALYSIS

A SWOT analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats allows you to assess factors that will impact your project. The following example applies to our clinic scenario of adding a point-of-care (POC) lipid testing device.

| Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Strengths POC lipid results are reliable (same results with improved delivery) Increased screening and rapid results → improved patient care Less blood volume needed Patients not constrained by lab hours have less missed work → better patient satisfaction More patients identified with dyslipidemia → more follow-up appointments Fewer follow-up appointments for lab discussions → increased appointment availability/access to care Billable procedure, new revenue stream Could increase appointment complexity (higher billing level) Empowering staff with more responsibilities Staff are trainable and quick to learn EHR is adaptable — orders can be added to existing EHR panels, provide some decision support Fewer inbox messages and incoming faxes → improved staff wellness | Weaknesses Physical space constraints Regular training required Additional task for staff in clinic workflow and inventory/ordering supplies → need to hire additional staff? Possible need for longer appointment times for testing/counseling PRN New workflow for staff and clinicians — change is hard! Up-front financial cost, ongoing maintenance fees More patients identified with dyslipidemia → more follow-up appointments, less access to care for new patients |

| External | Opportunities New relationship with manufacturer — they have other POC testing devices we may consider in the future | Threats Alienating current lab Some insurances don't cover POC lipid testing:

|

PHASE 2: PLANNING

During the planning phase, the project manager leverages the project charter to create a project plan that further defines the project's scope, budget, schedule, goals and deliverables, and the communication and reporting structure that will be followed. Several project planning tools can be helpful.

Stakeholder analysis. This involves identifying key stakeholders (e.g., patients, ordering clinicians, clinical support staff, vendors, leadership, legal, payers, and the finance department) and evaluating their level of participation/interest and their level of influence/power related to the project. Then, identify how best to involve and communicate with each group to manage expectations, anticipate potential conflicts, and mitigate potential detrimental effects on the project.

Work-breakdown structure. This is a list of all major tasks within the project subdivided into smaller tasks (and subtasks if needed), which makes the work less daunting and allows for more precise estimates of time, resources, and costs.

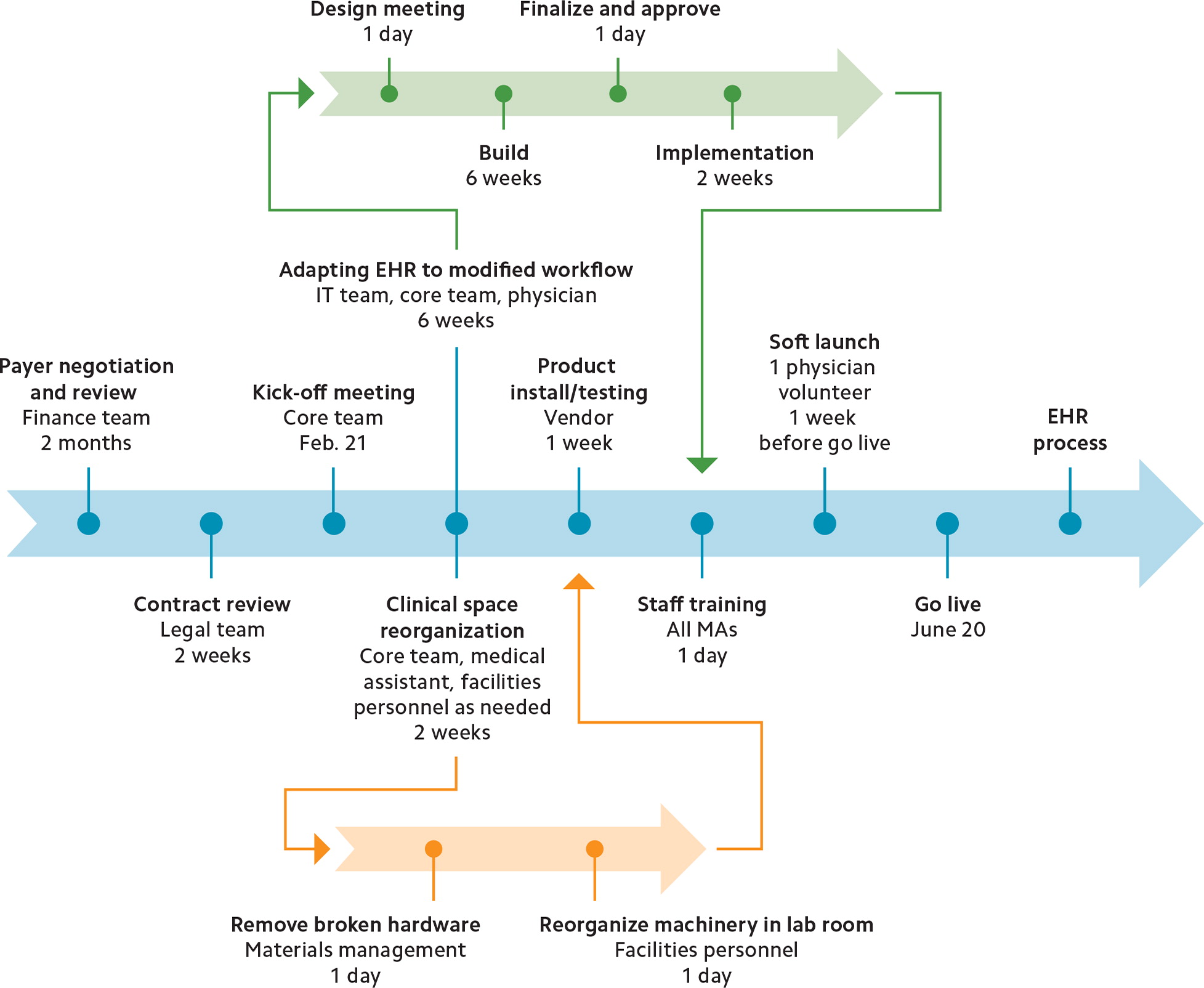

PERT chart. This is a diagram that focuses on the flow of successive tasks and their dependencies (see an example below). It helps define the critical path — the longest set of sequential tasks and the shortest possible time for completing the project.

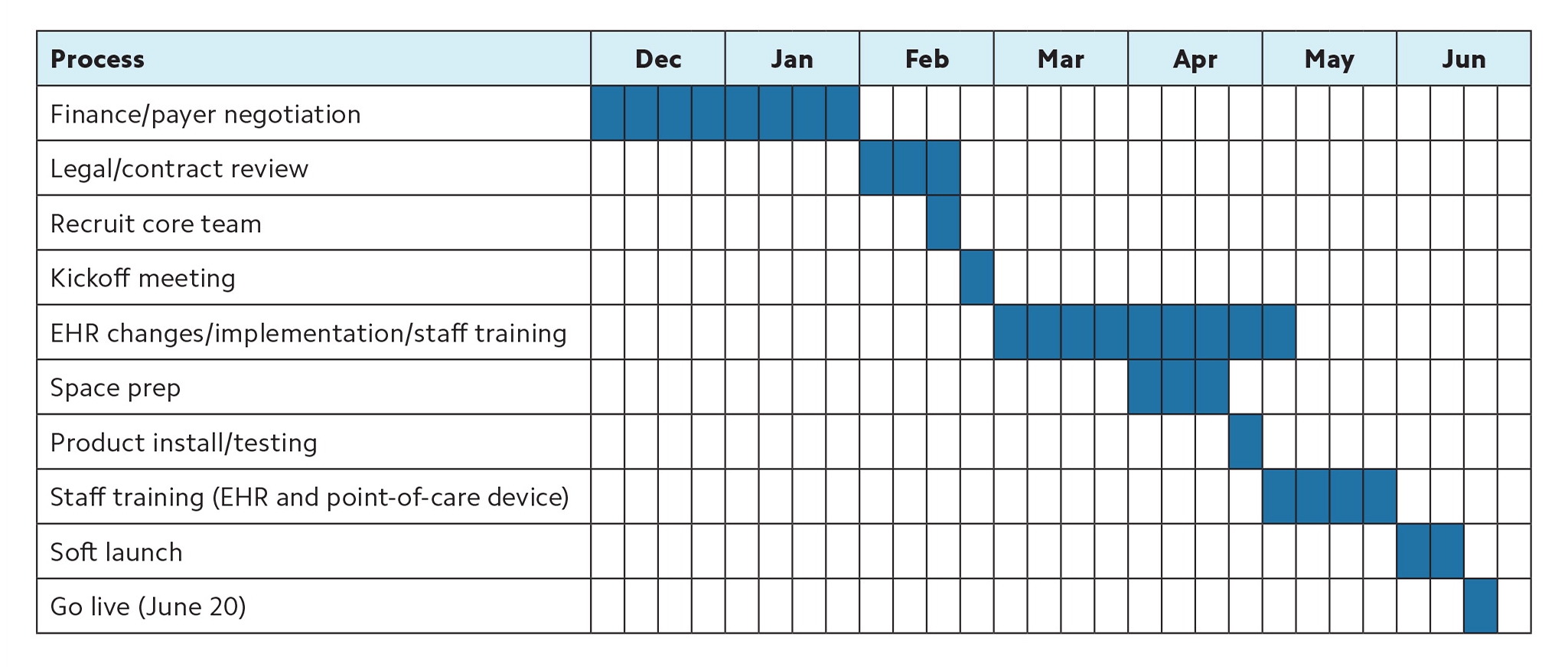

Gantt chart. This is a bar chart that lists high-level tasks and shows their relational timing and duration (see an example below). It is particularly useful for understanding how long tasks will take and which ones are running in parallel.

| Process | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance/payer negotiation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legal/contract review | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recruit core team | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kickoff meeting | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EHR changes/implementation/staff training | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Space prep | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Product install/testing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Staff training (EHR and point-of-care device) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Soft launch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Go live (June 20) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SMART or CLEAR goals. When drafting goals for the project, consider using a framework like SMART or CLEAR. SMART goals are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound, which helps frame goals in a way that is empirically quantifiable. For example, “Increase completed lipid screenings by 50% from baseline by six months after point-of-care lipid testing is implemented into workflow, with metrics reported monthly.” CLEAR goals are collaborative (involving a variety of stakeholders), limited (ensuring goals fall within the timeline, budget, and scope of the project), emotional (tapping into stakeholders' passions and aligning their interests with the purpose of the project), appreciable (breaking large goals down into smaller tasks for more frequent and measurable milestones), and refinable (allowing for flexibility to adjust goals if unanticipated situations arise). For example, “A core team comprised of at least one representative from each clinical stakeholder group will implement the point-of-care device by August 2023. Through weekly working sessions, the team will assign tasks and assess milestones following a three-month implementation schedule, as recommended by the vendor, and will present updates at monthly staff meetings.”

PHASE 3: EXECUTION

This is the phase where all your planning efforts finally get put into action. The project manager typically hosts a kickoff meeting to lay out the timeline, form teams, delegate tasks, and assign resources. The focus is on developing, testing, and achieving the project deliverables. For example, in our clinic scenario, deliverables might include installing the point-of-care lipid testing device, reorganizing the supply room, creating an order set in the EHR, and training staff.

Projects will encounter challenges during execution, and the project manager is responsible for handling unanticipated risks, minimizing their impact on the project, and keeping team leads, stakeholders, and end users informed. For example, let's say you discover mold growing from a slow leaking pipe while reorganizing the lab workroom. The drywall will need to be replaced after the pipe is repaired, and existing lab supplies and reagents sensitive to humidity will also need to be replaced. You adjust the project timeline to accommodate this delay and update relevant team members and stakeholders. When the clinic manager requests for you to coordinate the repair of the room, you decline, as this is outside the scope of your project, but you request regular updates.

To keep the team motivated during the project execution phase, make sure to celebrate key milestones, check in with team members to see how they're holding up, and empower them to make decisions and to take the necessary steps to complete their work.

PHASE 4: MONITORING AND CONTROL

In practice, the monitoring phase runs in parallel with the execution phase. Select two to five key performance indicators to monitor progress on different aspects of the project such as timeliness, budget, quality, or effectiveness. For example, to ensure timeliness, you may want to monitor the on-time completion rate for assigned tasks and set a goal for task completion within three days of the due date. If key performance indicators aren't being met, you'll need to identify the problem (obstacles, scope creep, etc.) and implement necessary changes.

Some monitoring will need to continue post-launch. For example, in the clinic scenario, one goal was to “increase completed lipid screenings by 50% from baseline by six months after point-of-care lipid testing is implemented into the workflow.” This measurement work should be assigned to a team member during the next phase.

PHASE 5: CLOSURE

At this stage, the project has launched, but the work isn't finished yet. The project manager will need to review the project plan to ensure all deliverables have been met and then share results with the project sponsor and stakeholders. They will transition any ongoing responsibilities to the appropriate team members. For example, ongoing maintenance and staff retraining might be delegated to the clinic director, while monitoring the effectiveness of the new process might be assigned to a quality improvement team.

Regardless of the project outcome, the project manager should debrief the team about how the process went — what went well and what aspects did not run smoothly and could be improved. This step is useful for improving future projects and increasing the chances of success.

RAPID RESULTS AND AGILE TEAMS

We would be remiss if we did not briefly mention two additional approaches to project management.

Rapid-results initiatives. These are essentially miniature versions of a project, both in time (restricted to 90–100 days) and scope (for example, only one physician and staff member would implement in-clinic lipid screening into their workflow). This is a low-risk option that allows you to test critical assumptions on a small scale and make early corrections. It also can spark interest and innovation, and boost morale by demonstrating project benefits.5

Agile. Requirements and objectives often evolve over the course of a project, and this can cause projects to fail if the team doesn't know how to respond. The “agile” method places high value on flexibility and adaptability, empowerment of team members, open communication, experiential learning, and rapid decision making.6 Nimble teams adapt faster to lessons learned, which leads to better results for patients, the team, and the organization.7

So, the next time you're asked to lead a project (or you volunteer), follow the prescription for project management success: start with the proven five-phased process, make use of common tools, and embrace rapid results and agile teams.