Patients may suffer due to their family member's substance use disorder but hesitate to discuss it because of stigma and shame. Primary care physicians can help.

Fam Pract Manag. 2024;31(6):26-29

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

Rachel is a 55-year-old woman with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus who came to the clinic for a same-day sick visit because of worsening leg swelling. She also reports mild headaches and insomnia. Her last office visit was three years ago, and at that time her chronic conditions (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes) were under control. At the current visit, her blood pressure is elevated to 175/110 mm Hg and her A1C is 9.3%. Her current medications include lisinopril, atorvastatin, and metformin. She has a full-time job and lives with her husband. She cannot think of any potential triggers or factors that might have contributed to her worsening chronic conditions. When you ask if she's been under a lot of stress lately, she sighs wearily and nods “yes.”

KEY POINTS

Substance use disorder (SUD) affects not only the person using substances but also their family members.

Primary care physicians can identify and address the unique issues of family members of people with substance use disorder (FM-PWSUD) by creating psychological safety, mitigating bias, and using non-stigmatizing and person-first language.

A one-question screening tool, referral to community resources, and continued follow up can also be effective.

THE EFFECT OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER ON FAMILY MEMBERS

More than 40 million people live with substance use disorder (SUD) in the U.S., according to the latest report from the federal government.1 SUD negatively affects not only the individuals using substances but also the family members of people with SUD (FM-PWSUD). A 2017 Pew Research Center study showed that nearly half of U.S. adults have a family member or close friend with a current or past drug addiction.2 FM-PWSUD may experience stigma, low self-esteem, and self-neglect as a result of taking care of their family member. Although evidence is growing about how to manage individuals with SUD, evidence is lacking about how to manage the issues their family members face. Many FM-PWSUD may not bring up their family issues due to hesitation and shame unless health care workers directly address the topic with them. Given the high prevalence of FM-PWSUD and the negative effects on physical, psychological, and social well-being, family physicians are well-suited to provide a holistic approach to FM-PWSUD.3–6

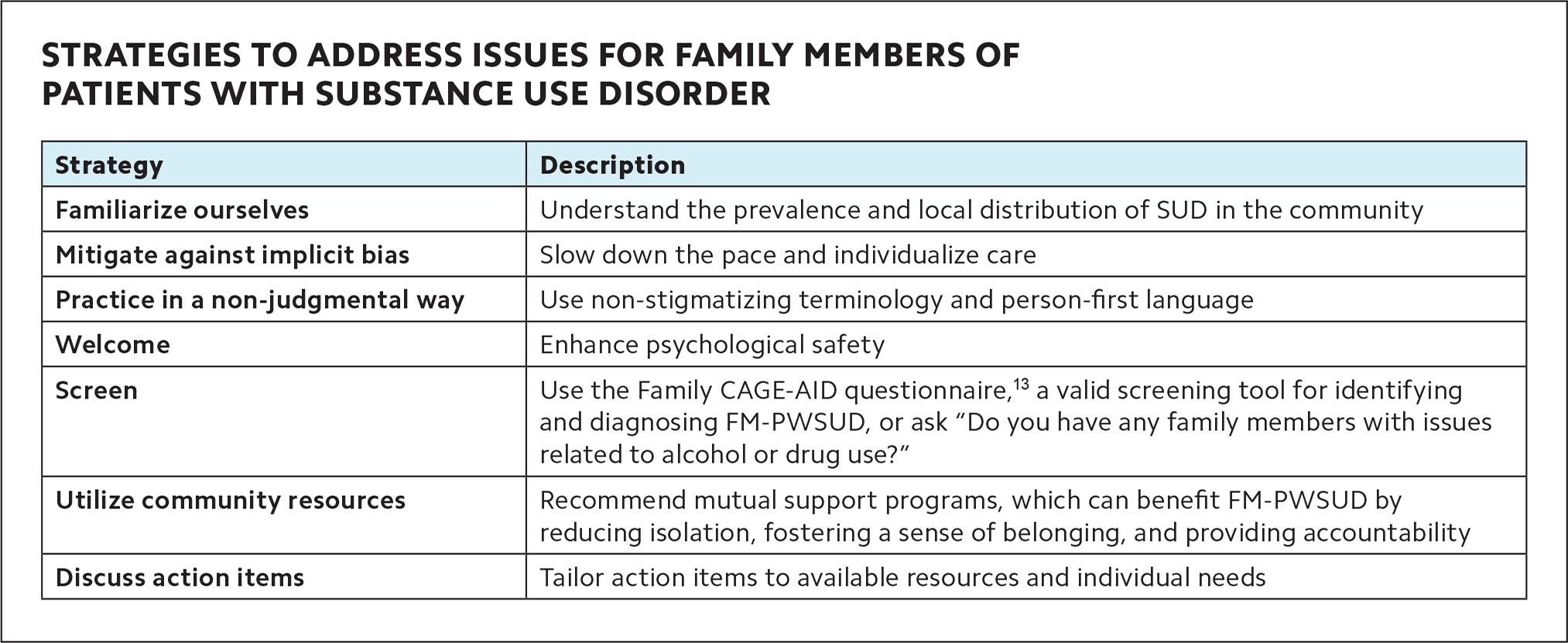

We developed a set of practical strategies for addressing issues involving FM-PWSUD in our busy family medicine practice. We recognize that many family physicians are pressed for time and may not think it is realistic to add something new to their plate. However, we have found that addressing the unique issues related to FM-PWSUD has helped us manage their overall care more efficiently and effectively. Below, we present several strategies using “FM-PWSUD” as a mnemonic across three action areas — recognize, identify, and approach.

STRATEGIES TO ADDRESS ISSUES FOR FAMILY MEMBERS OF PATIENTS WITH SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Familiarize ourselves | Understand the prevalence and local distribution of SUD in the community |

| Mitigate against implicit bias | Slow down the pace and individualize care |

| Practice in a non-judgmental way | Use non-stigmatizing terminology and person-first language |

| Welcome | Enhance psychological safety |

| Screen | Use the Family CAGE-AID questionnaire,13 a valid screening tool for identifying and diagnosing FM-PWSUD, or ask “Do you have any family members with issues related to alcohol or drug use?” |

| Utilize community resources | Recommend mutual support programs, which can benefit FM-PWSUD by reducing isolation, fostering a sense of belonging, and providing accountability |

| Discuss action items | Tailor action items to available resources and individual needs |

RECOGNIZE

The first step to support FM-PWSUD is to recognize the problem and potential barriers to addressing it. The following are some initial strategies.

F: Familiarize ourselves. As family physicians, we should seek to understand the prevalence and distribution of SUD in our local communities and its far-reaching effects. Many patients whose family members use substances may hesitate to disclose their struggles because they are afraid others will judge them. They may also assume that they are not supposed to talk about someone else's condition during their own medical encounter. However, these patients can experience poor social, physical, mental, and financial health,3,5,7,8,9 and they may have increased prevalence of conditions such as depression, anxiety, and diabetes.

M: Mitigate against implicit bias. Each of us likely have our own biases that we need to examine.10 If we make assumptions about who has substance problems based on stereotypes, for example, it can affect how we screen for SUD and talk to patients and their family members. The reality is that SUD can affect any individual and family regardless of age, race, ethnicity, gender, and social status. Slowing the pace of patient interactions and individualizing care can help mitigate implicit bias.10

IDENTIFY

Despite the prevalence of FM-PWSUD, their unique issues have been largely under-recognized in health care, in part because of their hesitation to disclose their struggles due to the stigma and shame around SUD. To effectively identify FM-PWSUD, we must take steps to create psychological safety.

P: Practice in a non-judgmental way. Words matter in addiction medicine,11 and our words can change how we provide patient care.12 Using non-stigmatizing terminology and person-first language (e.g., “patient” or “person with substance use disorder” instead of “user,” “drug abuser,” or “addict”) and normalizing questions about SUD can help lessen the potential for judgment that patients and their family members perceive. All staff members should be on the same page regarding practicing in a non-judgmental way because patients interact with them in addition to the physician.

W: Welcome. Addiction care tends to involve sensitive or traumatic experiences, and patients may hesitate to share those experiences. To create a welcoming environment, consider placing flyers or resources (e.g., describing the prevalence of SUD and providing the contact information for helpful organizations) in the waiting room, exam room, or restroom. This simple step can enhance psychological safety and encourage patients to discuss their family members' SUD with their physician.

S: Screen. Evidence to support screening all patients for FM-PWSUD is lacking; however, when you suspect SUD could be an issue in a patient's family, the “Family CAGE-AID” questionnaire is a valid screening tool for identifying and diagnosing FM-PWSUD.13 Alternatively, given the limited time available in most clinical settings, we may simply ask a brief question such as “Do you have any family members with issues related to alcohol or drug use?” Screening for FM-PWSUD might be especially helpful for patients who have worsening or persistent chronic conditions despite traditional approaches.

APPROACH

Once we identify FM-PWSUD, the next step is to better understand how their family members' SUD affects various aspects of their lives, including their health, and then address their unique issues. We have found it is best to use a multidisciplinary approach to meet their complex needs, often including mental health, housing, and social service providers.

U: Utilize community resources. Mutual support programs benefit FM-PWSUD by reducing isolation, fostering a sense of belonging, and providing accountability. Examples include Al-Anon (a mutual support program for people whose lives have been affected by someone else's drinking or drug use), Alateen (a part of the Al-Anon Family Groups for young people), Nar-Anon (a 12-step program for family and friends of people with narcotics addiction), and Family Anonymous (a 12-step program for family and friends of individuals with drug, alcohol, or related behavioral issues). Furthermore, practices can provide contact information for SUD clinics or community resources so that patients can share it with their family members with SUD.

D: Discuss action items. Action items should be tailored to individual needs and should take into account available resources (e.g., join a support program, follow the care plan for chronic conditions, see a counselor, or create a goal related to stress reduction). Practices should then follow up on the patient's conditions through phone calls, portal messages, or virtual/in-person encounters.

DON'T FORGET TO CODE FOR IT

When exploring and addressing FM-PWSUD issues, primary care physicians should use relevant ICD-10 codes and bill for their efforts in order to sustain this important work. Proper diagnosis coding can also help increase awareness of the unique issues FM-PWSUD face and prompt other health care providers to discuss these issues, because they remain a part of the problem list. You can use ICD-10 code Z63.72, “Alcoholism and drug addiction in family,” for encounters where you discuss issues related to family members with SUD. Additionally, time spent discussing these issues can add to the visit time and justify a higher E/M code.

CASE CONTINUES

To explore potential reasons for your patient Rachel's worsening conditions, you decide to ask about FM-PWSUD. You explain that it's common for individuals to have worsening health conditions when they're stressed and caring for others, and you ask, “Do you have any family members with issues related to alcohol or drug use?” Rachel discloses that her husband has struggled with opioid use disorder, affecting their relationship and finances. He recently became unemployed after missing days at work, which worsened his drug use due to social isolation and boredom.

Rachel is concerned about him overdosing whenever she leaves the house. Furthermore, she acknowledges feeling overwhelmed by her full-time job and assuming all household chores, and says she began to eat more snacks to cope with stress and stopped taking her medications due to financial strains. You recommend she attend a Nar-Anon 12-step program, connect her with a drug discount program, and provide her with the contact information for a clinic where her husband can receive comprehensive care for his opioid use disorder and other health problems. You follow up six weeks later, and Rachel reports she has resumed all medications and her leg swelling, headaches, and insomnia have resolved. Her blood pressure and diabetes are back under control. She is grateful for your understanding and assistance regarding the issues she experiences as a FM-PWSUD.

MOVING FORWARD

The unique issues of family members of people with SUD have been under-recognized in health care, negatively affecting their health outcomes. The mnemonic FM-PWSUD can help primary care clinicians identify and address the issues these patients face, starting with ensuring their psychological safety. Family physicians are well-positioned to raise awareness and serve their community by managing the needs of FM-PWSUD and those with SUD.