A more recent article on common rashes and skin changes in newborns is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):47-52

This is part I of a two-part article on newborn skin. Part II, “Birthmarks,” appears in this issue of AFP on page 56.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Rashes are extremely common in newborns and can be a significant source of parental concern. Although most rashes are transient and benign, some require additional work-up. Erythema toxicum neonatorum, acne neonatorum, and transient neonatal pustular melanosis are transient vesiculopustular rashes that can be diagnosed clinically based on their distinctive appearances. Infants with unusual presentations or signs of systemic illness should be evaluated for Candida, viral, and bacterial infections. Milia and miliaria result from immaturity of skin structures. Miliaria rubra (also known as heat rash) usually improves after cooling measures are taken. Seborrheic dermatitis is extremely common and should be distinguished from atopic dermatitis. Parental reassurance and observation is usually sufficient, but tar-containing shampoo, topical ketoconazole, or mild topical steroids may be needed to treat severe or persistent cases.

A newborn's skin may exhibit a variety of changes during the first four weeks of life. Most of these changes are benign and self-limited, but others require further work-up for infectious etiologies or underlying systemic disorders. Nearly all of these skin changes are concerning to parents and may result in visits to the physician or questions during routine newborn examinations. Thus, physicians who care for infants must be able to identify common skin lesions and counsel parents appropriately. Part I of this article reviews the presentation, prognosis, and treatment of the most common rashes that present during the first four weeks of life. Part II of this article, which appears in this issue of AFP, discusses the identification and management of birthmarks that appear in the neonatal period.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Infants who appear sick and have vesiculopustular rashes should be tested for Candida, viral, and bacterial infections. | C | 7, 8 |

| Acne neonatorum usually resolves within four months without scarring. In severe cases, 2.5% benzoyl peroxide lotion can be used to hasten resolution. | C | 10 |

| Miliaria rubra (also known as heat rash) responds to avoidance of overheating, removal of excess clothing, cool baths, and air conditioning. | C | 6 |

| Infantile seborrheic dermatitis usually responds to conservative treatment, including petrolatum, soft brushes, and tar-containing shampoo. | C | 13 |

| Resistant seborrheic dermatitis can be treated with topical antifungals or mild corticosteroids. | B | 17–19 |

Transient Vascular Phenomena

Newborn vascular physiology is responsible for two types of transient skin color changes: cutis marmorata and harlequin color change. These transient vascular phenomena represent normal newborn physiology rather than actual skin rashes, but they often cause parental concern.

CUTIS MARMORATA

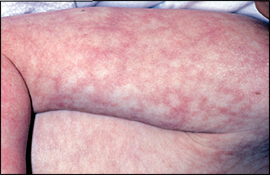

Cutis marmorata is a reticulated mottling of the skin that symmetrically involves the trunk and extremities (Figure 1). I t is caused by a vascular response to cold and generally resolves when the skin is warmed. A tendency to cutis marmorata may persist for several weeks or months, or sometimes into early childhood.2No treatment is indicated.

HARLEQUIN COLOR CHANGE

Harlequin color change occurs when the newborn lies on his or her side. It consists of erythema of the dependent side of the body with simultaneous blanching of the contralateral side. The color change develops suddenly and persists for 30 seconds to 20 minutes. It resolves with increased muscle activity or crying. This phenomenon affects up to 10 percent of full-term infants, but it often goes unnoticed because the infant is bundled.3 It occurs most commonly during the second to fifth day of life and may continue for up to three weeks. Harlequin color change is thought to be caused by immaturity of the hypothalamic center that controls the dilation of peripheral blood vessels.

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum

Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common pustular eruption in newborns. Estimates of incidence vary between 40 and 70 percent.4 It is most common in infants born at term and weighing more than 2,500 g (5.5 lb).5 Erythema toxicum neonatorum may be present at birth but more often appears during the second or third day of life. Typical lesions consist of erythematous, 2- to 3-mm macules and papules that evolve into pustules6 (Figure 2). Each pustule is surrounded by a blotchy area of erythema, leading to what is classically described as a “flea-bitten” appearance. Lesions usually occur on the face, trunk, and proximal extremities. Palms and soles are not involved.

Several infections (e.g., herpes simplex, Candida, and Staphylococcus infections) also may present with vesicopustular rashes in the neonatal period (Table 1)6,7; infants who appear sick or who have an atypical rash should be tested for these infections.8 In healthy infants, the diagnosis of erythema toxicum neonatorum is made clinically and can be confirmed by cytologic examination of a pustular smear, which will show eosinophilia with Gram, Wright, or Giemsa staining. Peripheral eosinophilia may also be present.7

The etiology of erythema toxicum neonatorum is not known. Lesions generally fade over five to seven days, but they may recur for several weeks. No treatment is needed, and the condition is not associated with any systemic abnormality.

| Class | Cause | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Group A or B Streptococcus Listeria monocytogenes Pseudomonas aeruginosa Staphylococcus aureus Other gram-negative organisms | Other signs of sepsis usually present Elevated band count, positive blood culture; Gram stain of intralesional contents shows polymorphic neutrophils |

| Fungal | Candida | Presents within 24 hours after birth if congenital, after one week if acquired during delivery Thrush is common Potassium hydroxide preparation of intralesional contents shows pseudohyphae and spores |

| Spirochetal | Syphilis | Rare Lesions on palms and soles Suspect if results of maternal rapid plasma reagin or venereal disease research laboratory test positive or unknown |

| Viral | Cytomegalovirus Herpes simplex Varicella zoster | Crops of vesicles and pustules appear on erythematous base For herpes simplex and varicella zoster, Tzanck test of intralesional contents shows multinucleated giant cells |

Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis

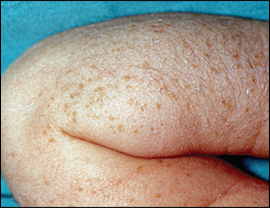

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis is a vesiculopustular rash that occurs in 5 percent of black newborns, but in less than 1 percent of white newborns.6,9 In contrast with erythema toxicum neonatorum, the lesions of transient neonatal pustular melanosis lack surrounding erythema (Figure 3). In addition, these lesions rupture easily, leaving a collarette of scale and a pigmented macule that fades over three to four weeks. All areas of the body may be affected, including palms and soles.

Clinical recognition of transient neonatal pustular melanosis can help physicians avoid unnecessary diagnostic testing and treatment for infectious etiologies. The pigmented macules within the vesicopustules are unique to this condition; these macules do not occur in any of the infectious rashes.9 Gram, Wright, or Giemsa staining of the pustular contents will show polymorphic neutrophils and, occasionally, eosinophils.

Acne Neonatorum

Neonatal acne is thought to result from stimulation of sebaceous glands by maternal or infant androgens. Parents should be counseled that lesions usually resolve spontaneously within four months without scarring. Treatment generally is not indicated, but infants can be treated with a 2.5% benzoyl peroxide lotion if lesions are extensive and persist for several months.7 Parents should apply a small amount of benzoyl peroxide to the antecubital fossa to test for local reaction before widespread or facial application. Severe, unrelenting neonatal acne accompanied by other signs of hyperan-drogenism should prompt an investigation for adrenal cortical hyperplasia, virilizing tumors, or underlying endocrinopathies.10

Milia

Milia are 1- to 2-mm pearly white or yellow papules caused by retention of keratin within the dermis. They occur in up to 50 percent of newborns.11 Milia occur most often on the forehead, cheeks, nose, and chin, but they may also occur on the upper trunk, limbs, penis, or mucous membranes. Milia disappear spontaneously, usually within the first month of life, although they may persist into the second or third month.11 Milia are a common source of parental concern, and simple reassurance about their benign, self-limited course is appropriate.

Miliaria

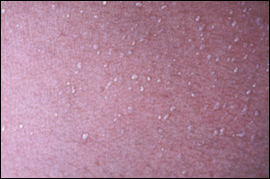

Miliaria results from sweat retention caused by partial closure of eccrine structures. Both milia and miliaria result from immaturity of skin structures, but they are clinically distinct entities. Miliaria affects up to 40 percent of infants and usually appears during the first month of life.12 Several clinically distinguishable subtypes exist; miliaria crystallina and miliaria rubra are the most common.

Miliaria crystallina is caused by superficial eccrine duct closure. It consists of 1- to 2-mm vesicles without surrounding erythema, most commonly on the head, neck, and trunk (Figure 5). Each vesicle evolves, with rupture followed by desquamation, and may persist for hours to days.

Miliaria rubra, also known as heat rash, is caused by a deeper level of sweat gland obstruction (Figure 6). Its lesions are small erythematous papules and vesicles, usually occurring on covered portions of the skin. Miliaria crystallina and miliaria rubra are benign. Avoidance of overheating, removal of excess clothing, cooling baths, and air conditioning are recommended for management and prevention of these disorders.6

Seborrheic Dermatitis

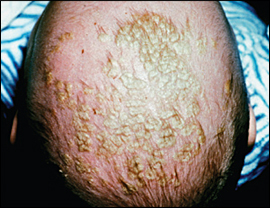

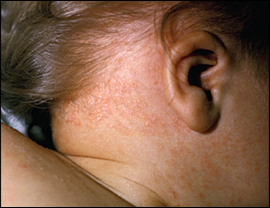

Seborrheic dermatitis is an extremely common rash characterized by erythema and greasy scales (Figures 7 and 8). Many parents know this rash as “cradle cap” because it occurs most commonly on the scalp. Other affected areas may include the face, ears, and neck. Erythema tends to predominate in the flexural folds and intertriginous areas, whereas scaling predominates on the scalp.13 Because seborrheic dermatitis often spreads to the diaper area, it is important to consider in the evaluation of diaper dermatitis.14

| Feature | Seborrheic dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | Usually within first month | After three months of age |

| Course | Self-limited, responds to treatment | Responds to treatment, but frequently relapses |

| Distribution | Scalp, face, ears, neck, diaper area | Scalp, face, trunk, extremities, diaper area |

| Pruritus | Uncommon | Ubiquitous |

The exact etiology of seborrheic dermatitis is unknown. Some studies have implicated the yeast Malassezia furfur (previously known as Pityrosporum ovale).15 Hormonal fluctuations may also be involved, which would explain why seborrheic dermatitis occurs most often in areas with a high density of sebaceous glands. Generalized seborrheic dermatitis accompanied by failure to thrive and diarrhea should prompt an evaluation for immunodeficiency.13

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis is usually self-limited, resolving within several weeks to several months. In one prospective study, children with infantile seborrheic dermatitis were reexamined 10 years later.16 Overall, 85 percent of children were free of skin disease at follow-up. Seborrheic dermatitis persisted in 8 percent of children, but the link between infantile and adult seborrheic dermatitis remains unclear. In addition, 6 percent of children in this study later were diagnosed with atopic dermatitis, illustrating the difficulty in distinguishing these conditions during infancy.

Given the benign, self-limited nature of seborrheic dermatitis in infants, a conservative stepwise approach to treatment is warranted. Physicians should begin with reassurance and watchful waiting. If cosmesis is a concern, scales can often be removed with a soft brush after shampooing. An emollient, such as white petrolatum, may help soften the scales. Soaking the scalp overnight with vegetable oil and then shampooing in the morning is also effective.

If seborrheic dermatitis persists despite a period of watchful waiting, several treatment options exist (Table 3).13,17–19 Tar-containing shampoos can be recommended as first-line treatment.13 Selenium sulfide shampoos are probably safe, but rigorous safety data in infants is lacking. The use of salicylic acid is not recommended because of concerns about systemic absorption.13

| Medication | Directions | Cost (generic)* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| White petrolatum | Apply daily | $3 for 30 g | May soften scales, facilitating removal with soft brush |

| Tar-containing shampoo | Use several times per week | $13 to $15 for 240 mL | Use when baby shampoo has failed Safe, but potentially irritating |

| Ketoconazole (Nizoral, brand no longer available in the United States), 2% cream or 2% shampoo | Cream: apply to scalp three times weekly Shampoo: lather, leave on for three minutes, then rinse. Use three times weekly | Cream: ($16 to $37 for 15 g) Shampoo: $30 to $33 for 120 mL ($16 to $38) | Small trial showed no systemic drug levels or change in liver function after one month of use |

| Hydrocortisone 1% cream | Apply every other day or daily | $2 to $4 for 30 g | Limit surface area to reduce risk of systemic absorption and adrenal suppression |

| May be especially effective for rash in flexural areas |

Evidence from small randomized controlled trials supports the use of topical antifungal creams or shampoos if treatment with tar-containing shampoo fails.17,20 Mild steroid creams are another commonly prescribed option. One meta-analysis found that topical ketoconazole (Nizoral, brand no longer available in the United States) and steroid creams are effective in the treatment of infantile seborrheic dermatitis, but ketoconazole may be better at preventing recurrences.18