Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(7):429-436

Related letter: Use of More Specific Terminology May Assist in Better Diagnosis of Abdominal Wall Injuries

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

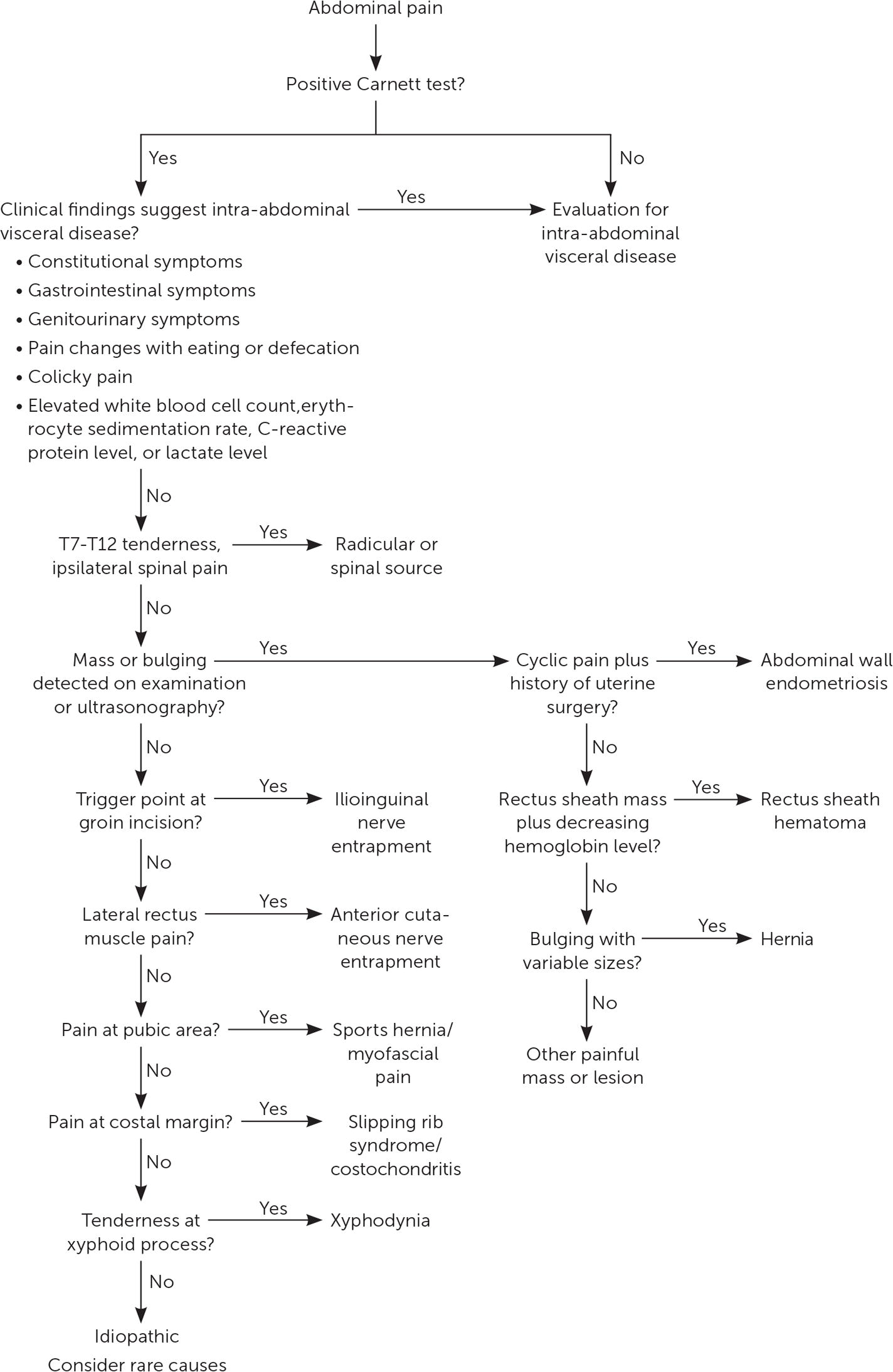

Abdominal wall pain is often mistaken for intra-abdominal visceral pain, resulting in expensive and unnecessary laboratory tests, imaging studies, consultations, and invasive procedures. Those evaluations generally are nondiagnostic, and lingering pain can become frustrating to the patient and clinician. Common causes of abdominal wall pain include nerve entrapment, hernia, and surgical or procedural complications. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome is the most common and frequently missed type of abdominal wall pain. This condition typically presents with acute or chronic localized pain at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis that worsens with position changes or increased abdominal muscle tension. Abdominal wall pain should be suspected in patients with no symptoms or signs of visceral etiology and a localized small tender spot. A positive Carnett test, in which tenderness stays the same or worsens when the patient tenses the abdominal muscles, suggests abdominal wall pain. A local anesthetic injection can confirm the diagnosis when there is 50% postprocedural pain improvement. Point-of-care ultrasonography may help rule out other abdominal wall pathologies and guide injections. The management of abdominal wall pain depends on the etiology. Reassurance and patient education can be helpful. Local injection with an anesthetic and a corticosteroid is an effective treatment for anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome, with an overall response rate of 70% to 99%. For refractory cases that require more than two injections, surgical neurectomy generally resolves the pain.

Pain originating from the abdominal wall has been described for nearly 100 years 1 but did not receive much attention until 1926, when a simple bedside test was proposed.2 Case reports in the early 1970s suggested that nerve entrapment could be the cause of abdominal wall pain and was able to be successfully treated with local injections.3,4 More recently, the consensus has been that abdominal wall pain is commonly unrecognized, overlooked, underdiagnosed, and understudied.5–11

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome should be suspected in patients with a localized small tender spot at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis. | C | 4, 16, 18, 21, 38 |

| The Carnett test is useful to support the diagnosis of abdominal wall pain. | C | 2, 28, 32 |

| Local anesthetic injection with or without corticosteroids can diagnose and treat abdominal wall pain caused by nerve entrapment. | B | 10, 33–36 |

The prevalence of abdominal wall pain in the general population and primary care settings is not known, but it ranges from 5% to 67% in patients referred to subspecialists.12–14 A study of 100 consecutive patients referred to a pain clinic by gastroenterologists for chronic abdominal pain management found that 43 had abdominal wall pain, and that many were initially misdiagnosed with functional abdominal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, or a psychiatric disorder.13

Abdominal wall pain is an umbrella term that comprises many etiologies, the most common of which is benign nerve entrapment. Because of physicians' unfamiliarity with abdominal wall pain and concern about the consequences of missing serious pathology, evaluation is often misdirected toward costly and unnecessary laboratory tests, advanced imaging studies, consultations, and frequent clinic visits. Patients may be exposed to unwarranted invasive procedures such as endoscopy, laparoscopy, or cholecystectomy. These procedures have a high cost: one study calculated that the typical patient had abdominal wall pain for 25 months before diagnosis, with an annual direct health care cost of more than $1,100.12 This highlights the importance of early consideration of abdominal wall pain. The critical task for clinicians is to distinguish benign etiologies from more serious intra- or extra-abdominal causes.

This article updates a previous American Family Physician article on abdominal wall pain with emerging data on point-of-care ultrasonography and surgical intervention.8

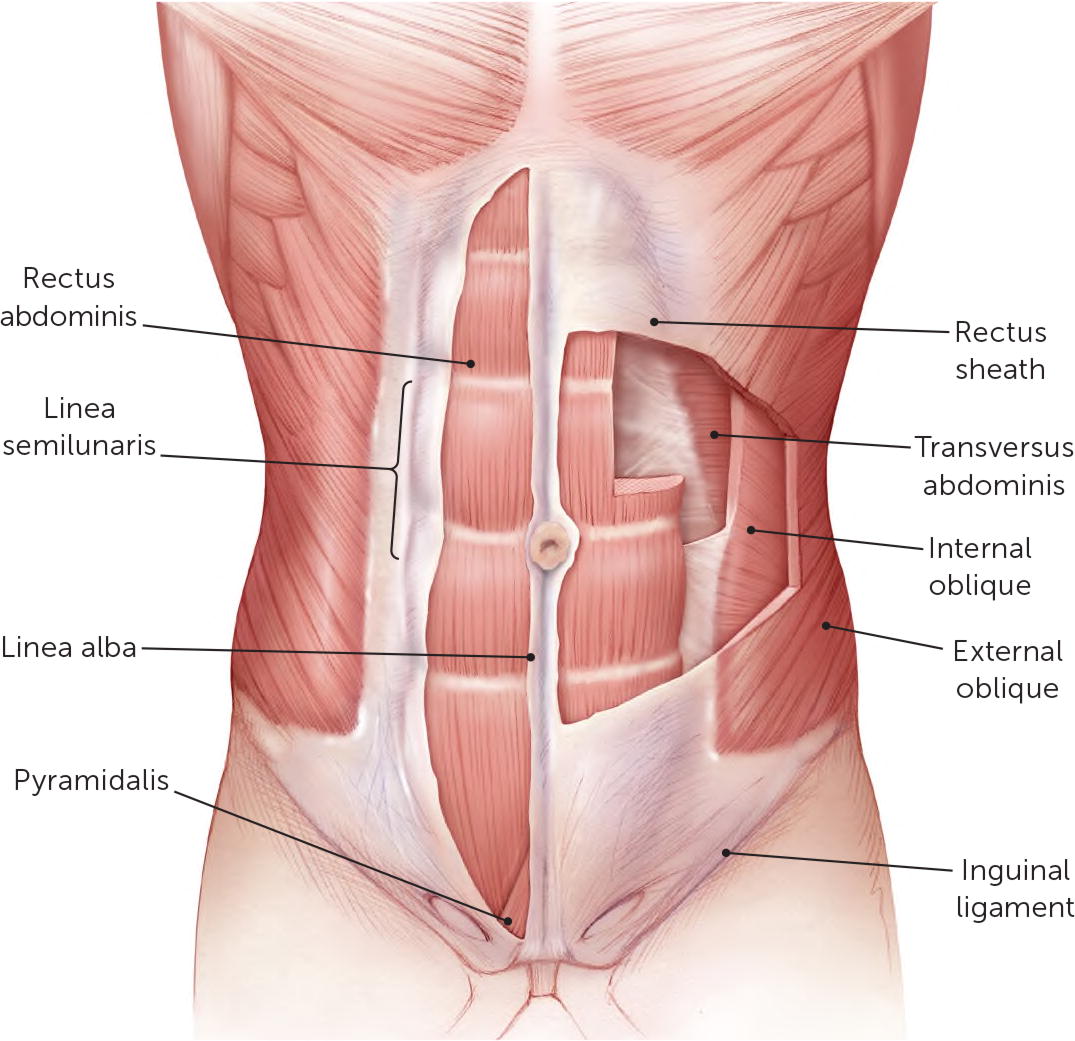

Applied Anterior Abdominal Wall Anatomy

Understanding the anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall will aid clinicians in diagnosing and treating abdominal wall pain. There are five pairs of muscles in the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1). Along the midline, the rectus abdominis can cause localized pain on the xyphoid process superiorly or in the pubic area inferiorly. The pyramidalis can also cause pubic area pain. The lateral abdominal wall is composed of—from superficial to deep—the external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominis muscles. Their aponeuroses fuse together, forming the rectus sheath that encloses the rectus abdominis (except the posterior quarter inferior to the arcuate line), the inguinal ligament inferiorly, the linea semilunaris lateral to the rectus abdominis, and the linea alba at the midline.15 These aponeuroses, as well as the navel and any surgical incision sites, are areas prone to hernia formation.

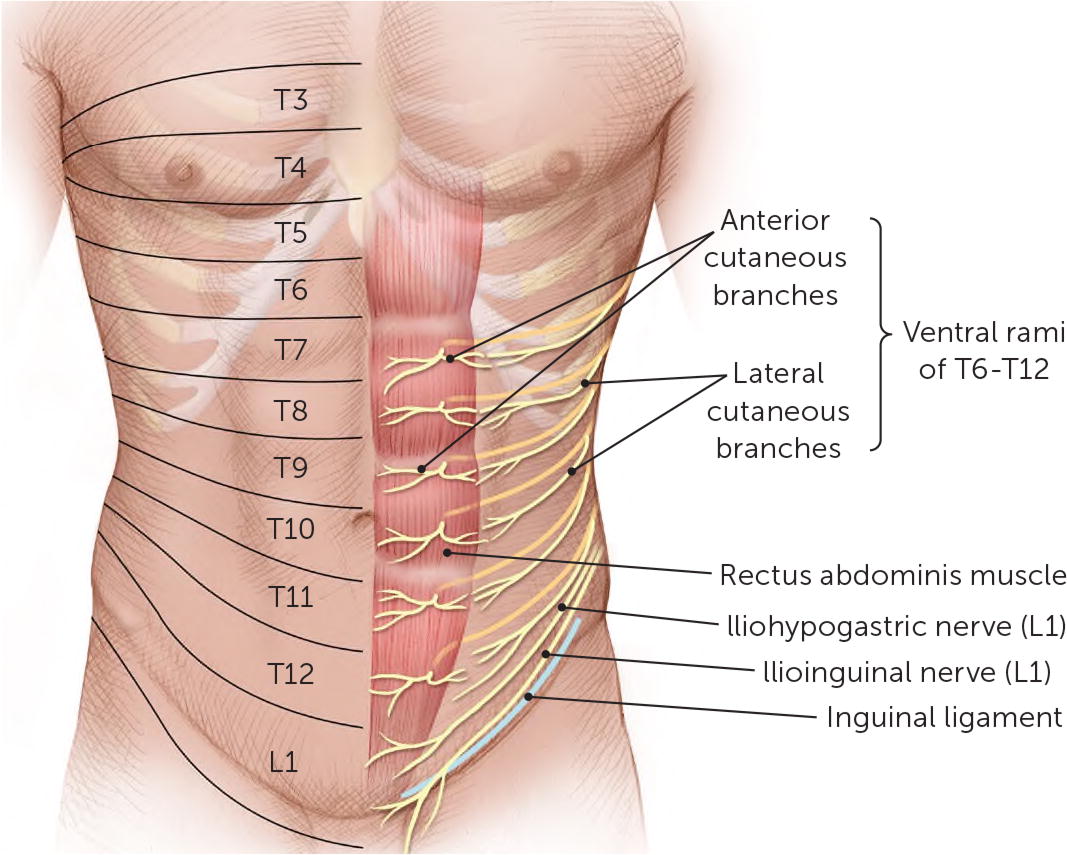

The nerves of the anterior abdominal wall are the ventral rami of the T6–L1 spinal nerves (Figure 2). It was originally thought that the terminal branches of the T7–T12 ventral rami enter the lateral posterior rectus abdominis at a 90-degree angle through a fibrous neurovascular channel, progressing anteriorly through the muscle and anterior rectus sheath to become the anterior cutaneous nerves of the abdomen. Once those nerves reach the overlying aponeurosis, the nerves again change course at 90-degree angles beneath the skin.16 A recent study indicates that their anatomy is far more complex.17 The L1 nerve bifurcates into the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves; the iliohypogastric nerve pierces the external oblique aponeurosis superior to the superficial inguinal ring, whereas the ilioinguinal nerve passes through the inguinal canal to emerge through the superficial inguinal ring.15

Etiologies and Differential Diagnoses

Abdominal wall pain can originate locally. Less commonly, it can be referred from intra-abdominal pathology, intrathoracic visceral pathology, or thoracic spinal radiculopathy.

The most common cause of abdominal wall pain is nerve entrapment at the lateral border of the rectus muscle; this is known as anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome.4,16 It is caused by compression of an anterior cutaneous nerve as it courses through the abdominal wall musculature and aponeuroses.16 Intra- or extra-abdominal pressure or scar formation causes traction on the nerve, leading to nerve irritation and, potentially, nerve ischemia.4,18 Ilioinguinal–iliohypogastric nerve entrapment is another common cause of lower abdominal pain in patients with a history of lower abdominal surgery, particularly inguinal herniorrhaphy, appendectomy, and procedures incorporating a Pfannenstiel incision.19 Diabetic neuropathy, thoracic spine radiculopathy, and postherpetic neuralgia are less common causes of abdominal wall pain.

Sports hernias are a common cause of groin pain in athletes, although the term is a misnomer because there is no classical herniation of soft tissue. Pain is thought to be caused by an imbalance between the strength of adductor and abdominal wall muscles and partial weakness of the posterior abdominal wall. There is evidence implicating nerve entrapment in some cases of sports hernias.20

True hernias, either incisional or spontaneous, may cause abdominal wall pain without noticeable bulging or obstructive symptoms. Incisional hernias can occur wherever there is an incision. Nonincisional hernias tend to be localized at the epigastric and umbilical areas in the midline or laterally in the groin or around the linea semilunaris. Spigelian hernias, which are rare defects in the transversus aponeurosis occurring at the junction of the rectus abdominis and linea semilunaris, often occur at or inferior to the arcuate line because the posterior rectus sheath is lacking in this area. Spigelian hernias can be difficult to clinically distinguish from anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome because of the location, although ultrasonography may help.21

Other less common benign causes of abdominal wall pain include abdominal wall muscle strain, abdominal wall endometriosis, and slipping rib syndrome; less common but potentially more serious causes include rectus sheath hematoma, abdominal wall infection, and intra-abdominal pathology with adhesion to the abdominal wall.22–27 An inflamed appendix with adhesion to the abdominal wall may cause localized pain but is generally associated with systemic symptoms.28

| Clinical finding | Intra-abdominal visceral pain | Abdominal wall pain |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced imaging findings | Often positive | Usually unremarkable |

| Carnett test | Negative | Positive |

| Constitutional symptoms | Anorexia, chills, fever, weight loss | Typically absent |

| Gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms | Altered bowel habits, dysuria, frequent urination, gastrointestinal bleeding, jaundice, nausea, vaginal bleeding or discharge, vomiting | Typically absent |

| Laboratory findings | Elevated white blood cell count, inflammatory markers, or serum lactate level | Usually within normal limits |

| Pain characteristics | Aggravated/relieved by eating or defecation; peristaltic pain | Unrelated to meals or bowel function; constant or fluctuating, nonperistaltic |

| Sex predominance | None | Females |

| Tender spot | Location depends on underlying pathology; relatively vague | Clearly identifiable superficial tender area < 2 cm, typically near the rectus abdominis |

| Condition | Clinical features |

|---|---|

| Abdominal wall endometriosis22,23 | Cyclic abdominal pain, history of laparotomy; mass often can be localized |

| Abdominal wall muscle injury | Usually caused by traumatic event; occurs mainly in athletes |

| Adiposis dolorosa (Dercum disease, Anders disease) | Obesity with multiple painful lipomas |

| Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome16 | Localized (< 2 cm) unilateral sharp pain, acute or chronic; retrograde radiation horizontally in the upper abdomen and obliquely downward in the lower abdomen (Valleix phenomenon); worsening with abdominal muscle movement; more prevalent in females |

| Desmoid tumor8 | Dysplastic tumor of connective tissue occurring in young patients (more often in females) |

| Diabetic thoracic polyradiculopathy29 | Severe, chronic abdominal pain in patients with diabetes; may affect sensory, motor, and autonomic functions; associated with other diabetic complications, weight loss, and paretic abdominal wall protrusion |

| Hernia (epigastric, hypogastric, umbilical, inguinal, incisional, and Spigelian)8 | Protuberance in abdominal wall that usually decreases in size when patient is supine; localized to a natural or iatrogenic weak spot on the abdominal wall |

| Herpes zoster | Pain and hyperesthesia preceding vesicular rash in dermatomal distribution |

| Idiopathic or myofascial pain syndrome | Localized abdominal wall pain with unclear etiology |

| Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment syndrome7 | History of surgery with a Pfannenstiel incision; iliac fossa pain radiating to the groin, proximal scrotum, labia majora, upper inner thigh, and back; altered sensory perception in affected areas and a trigger point medial and inferior to the anterosuperior iliac spine |

| Rectus sheath hematoma26 | Abdominal wall pain associated with a mass and decrease in hemoglobin level; commonly associated with abdominal trauma, intra-abdominal procedure, anticoagulation, or cough |

| Slipping rib syndrome24,25,28 | Upper abdomen or lower chest pain around the costal margin; caused by impingement of intercostal nerve between two costal cartilages (8th, 9th, or 10th) secondary to luxation of interchondral articulation; hooking maneuver or dynamic ultrasonography can be diagnostic |

| Sports hernia20 | Groin pain in athletes whose sport involves kicking and twisting while running; caused by abdominal wall weakness or injury; occurs without a palpable hernia |

| Thoracic spinal radiculopathy30 | Radicular symptoms in dermatomal or myotomal distribution; localized spine and paraspinal tenderness; myelopathy symptoms in severe cases |

| Visceral pain localized to the abdominal wall28 | Abdominal pain associated with constitutional or systemic symptoms; possible gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms |

| Xiphodynia31 | Reproducible lower chest or upper abdominal discomfort with light pressure on the xiphoid process; xiphoid process deformity may be observed |

Evaluation

A history and targeted physical examination, potentially complemented with local anesthetic injection or ultrasonography, generally can promptly and accurately identify the abdominal wall as the source of pain.

HISTORY

Abdominal wall pain is typically provoked by physical movement, such as lifting, bending, laughing, straining, and twisting. Therefore, a history regarding precipitating and associated factors is crucial in making the diagnosis. Questions about gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or constitutional symptoms are vital for ruling out intra-abdominal etiology. It is also important to ask about a history of abdominal surgery, injury, trauma, diabetes mellitus, or back problems to rule out neuropathic causes. The patient's ability to localize pain with a fingertip is an element of the history that is highly suggestive of abdominal wall pain.11 Patients with abdominal wall pain often have comorbid obesity.12 Validated screening tools can also be helpful; a systematic 18-item patient questionnaire (Table 3) can be used to differentiate anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome from irritable bowel syndrome, with a score of 10 or higher having 94% sensitivity and 92% specificity for anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome.6

| Question | Answer options | 1 point if: | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How often do you experience bloating or a feeling of gas in the intestines? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Sometimes or never | |

| 2. Does pain exist on different spots all over the abdomen? | Yes or no | No | |

| 3. Does pain dominate over discomfort? | Yes or no | Yes | |

| 4. How often do you have pain when lying on the affected side? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Mostly or regularly | |

| 5. How often does the stool have an abnormal consistency (e.g., hard and small, pencil thin, loose, watery)? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Sometimes or never | |

| 6. Does it feel like the pain originates just beneath the skin? | Yes or no | Yes | |

| 7. How often do you have sharp pain? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Mostly or regularly | |

| 8. Does it feel like the pain originates from the gastrointestinal tract? | Yes or no | No | |

| 9. How often do you feel an urgent need for bowel movement without producing stool (incomplete defecation)? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Sometimes or never | |

| 10. How often do you have pain when coughing, sneezing, or squeezing? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Mostly or regularly | |

| 11. Is the pain always located in the same spot? | Yes or no | Yes | |

| 12. Is the pain just lateral to the midline of the abdomen? | Yes or no | Yes | |

| 13. Is the pain related to an altered defecation pattern? | Yes or no | No | |

| 14. How often do you have pain with daily activities (e.g., walking, sitting, cycling, bending)? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Mostly or regularly | |

| 15. How often does the painful spot feel strange, different, or dull? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Mostly or regularly | |

| 16. How often does stress provoke the pain? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Sometimes or never | |

| 17. Can you show with the tip of your finger where the most intense pain is? | Yes or no | Yes | |

| 18. How often do you have pain when pushing on the tender spot? | Mostly, regularly, sometimes, or never | Mostly or regularly | |

| Total score: |

EXAMINATION

The Carnett test is a validated and crucial tool in the evaluation of abdominal wall pain.2,28 The clinician places the patient in the supine position and identifies the point of maximal tenderness on the abdomen; constant pressure is then applied to that spot. Next, the patient is asked to cross his or her arms over the chest, then to lift the head and shoulders from the examination table to tense the abdomina l muscles. An alternative variant is to have the patient raise both legs with knees extended. A positive test elicits stable or worsened pain, indicating abdominal wall etiology. A negative test, in which pain improves, suggests that the pain is likely of intra-abdominal or visceral origin. It can be challenging to interpret results in patients with psychogenic abdominal pain.

A modified Carnett test for pelvic pain has been described previously.32 In patients with tenderness during bimanual pelvic examination, the clinician should locate the spot of maximal tenderness and then remove his or her hand from the abdomen without changing the location and pressure of the vaginal fingers to see whether the pain changes. The clinician can then replace the abdominal hand on the tender spot and retract the vaginal finger to see whether the pain changes. The test is positive when external abdominal palpation elicits pain.

In addition to the Carnett test, other components of the physical examination include a pelvic examination for women with lower abdominal pain; a neurologic examination, including sensory dermatome determination; muscle strength testing; a thoracic spine examination; and detection of abdominal defects, masses, or bulging. The hooking maneuver, in which the examiner hooks curved fingers under the inferior rib margins and pulls anteriorly to reproduce pain in the lower chest and upper abdominal area, can help diagnose slipping rib syndrome.24

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING AND PROCEDURES

Ultrasonography, especially point-of-care ultrasonography, can be useful in evaluating abdominal wall pain. It can be used to detect masses, abscesses, hematomas, tissue edema, and slipping rib syndrome. It can also offer dynamic evaluation for hernia and provide guidance for therapeutic or diagnostic trigger point injection. Other advanced imaging modalities, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, are generally not needed unless there is diagnostic ambiguity or concern about intra-abdominal etiology.

Diagnostic trigger point injection with or without ultrasound guidance can help confirm the diagnosis of nerve entrapment.10,33–36 Ultrasound guidance is preferred because it provides needle visualization to avoid accidentally entering the abdominal cavity, and it helps the needle infiltrate the entire neurovascular channel in patients with suspected anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. In trigger point injection, 5 to 10 mL of 1% to 2% lidocaine is injected deep into the fascia and muscle at the point of maximal tenderness (see video below). Pain improvement of 50% or more confirms the diagnosis of abdominal wall pain. Pain resolution also occurs in about 20% to 30% of patients with anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome.5

Trigger Point Injection

Treatment

The management of abdominal wall pain depends on its etiology. Patient education and reassurance may decrease patient anxiety, which subsequently reduces clinic visit frequency and patient insistence on undergoing unnecessary expensive or invasive evaluations.

Oral analgesics, muscle relaxants, and antispasmodics are the most commonly prescribed medications for abdominal wall pain. However, their effectiveness is inconsistent, and their use is not evidence based.37 The same is true for local interventions such as icing, massage, and topical analgesics.

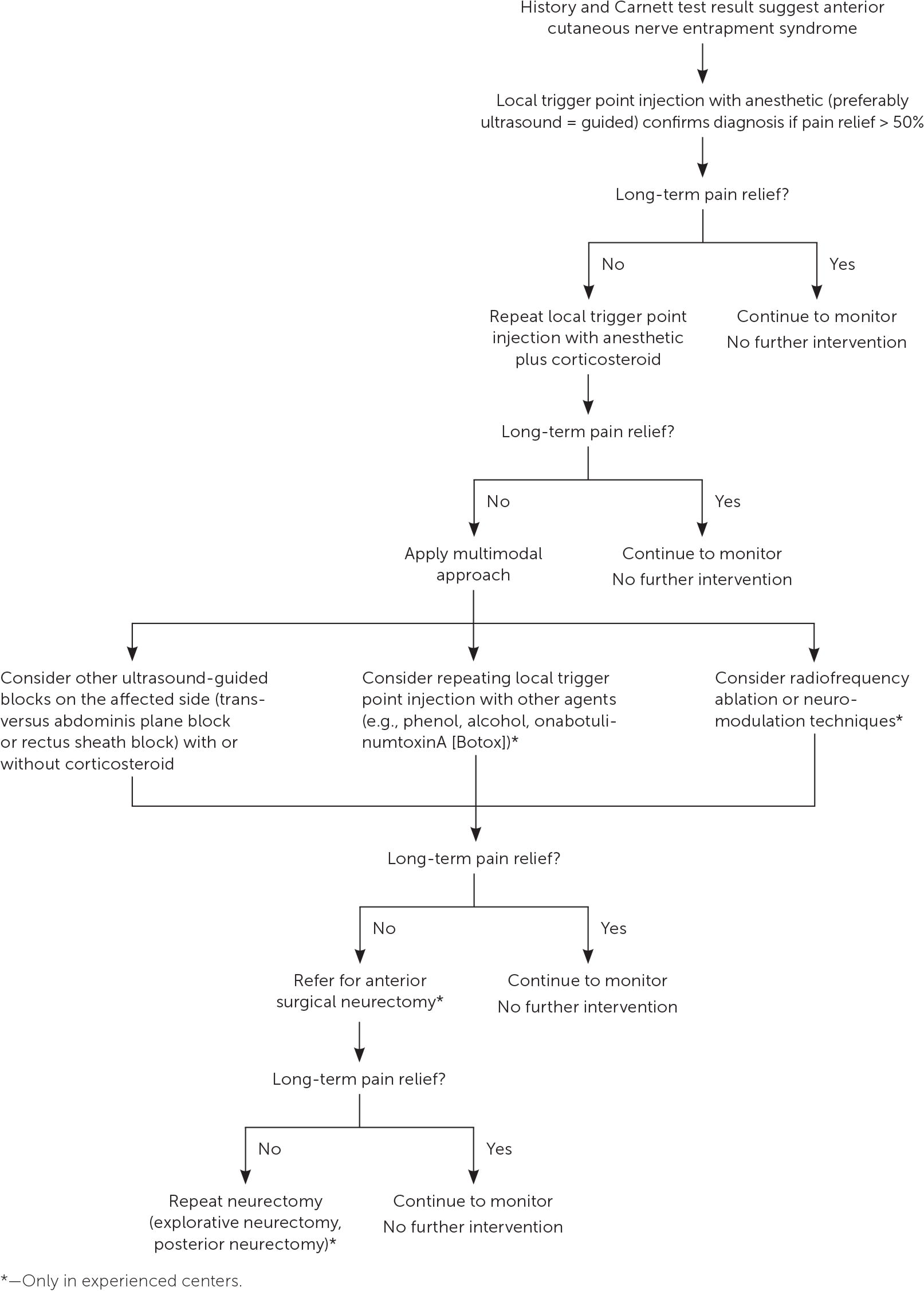

As discussed previously, ultrasound-guided trigger point injection can confirm the diagnosis of abdominal wall pain caused by nerve entrapment while also providing symptom relief. Because of the relatively high failure rate of local anesthetic injection, a combination of local anesthetic and other agents such as corticosteroids, onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), and phenol are sometimes used. Corticosteroids are the most commonly used and have a response rate of 70% to 99%10,33–36 (eTable A). Alternatives to local injection include transversus abdominis plane block, rectus sheath plane block, chemical neurolysis with phenol, or radiofrequency denervation; however, the effectiveness and safety of these modalities are not well documented.37 Surgical neurectomy, in which a portion of the entrapped nerve is surgically removed, can be considered in cases of anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome that require more than two injections. A stepwise management approach— beginning with local trigger point injection followed by neurectomy—is recommended37–39 (eFigure A).

Surgical intervention may be necessary for hernia, endometriosis, slipping rib syndrome, abdominal wall mass or abscess, rectal sheath hematoma, xiphodynia, or sports hernia when conservative management is ineffective.

| Corticosteroid | Anesthetic | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Betamethasone, 3 mg | Bupivacaine (Marcaine) 0.25% or lidocaine 1%, volume not specified | One injection: 70%A1 |

| Overall (≥ 2 injections): NAA1 | ||

| Betamethasone, 4 mg | 2 mL bupivacaine 0.5% plus 3 mL lidocaine 2% | One injection: 68%A2 |

| Overall (≥ 2 injections): 95%A2 | ||

| Methylprednisolone, 40 mg | Bupivacaine 0.25% or lidocaine 1%, volume not specified | One injection: 70%A1 |

| Overall (≥ 2 injections): NAA1 | ||

| 1.5 to 2 mL lidocaine 2% | One injection: 78%A3 | |

| Overall (≥ 2 injections): 99%A3 | ||

| Triamcinolone, 10 mg | 1 mL lidocaine 2% | Overall: 89%A4 |

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Suleiman and Johnston.8

Data Sources: We searched PubMed, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and Guidelines.gov using the following terms in various combinations: diagnosis, management, treatment, therapy, abdominal wall pain, anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment, ultrasound, and trigger point injection. Search dates: February 2017 to June 2018.