Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(3):168-175

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Hirsutism is the excessive growth of terminal hair in a typical male pattern in a female. It is often a sign of excessive androgen levels. Although many conditions can lead to hirsutism, polycystic ovary syndrome and idiopathic hyperandrogenism account for more than 85% of cases. Less common causes include idiopathic hirsutism, nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumors, medications, hyperprolactinemia, thyroid disorders, and Cushing syndrome. Women with an abnormal hirsutism score based on the Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system should be evaluated for elevated androgen levels. Women with rapid onset of hirsutism over a few months or signs of virilization are at high risk of having an androgen-secreting tumor. Hirsutism may be treated with pharmacologic agents and/or hair removal. Recommended pharmacologic therapies include combined oral contraceptives, finasteride, spironolactone, and topical eflornithine. Because of the length of the hair growth cycle, therapies should be tried for at least six months before switching treatments. Hair removal methods such as shaving, waxing, and plucking may be effective, but their effects are temporary. Photoepilation and electrolysis are somewhat effective for long-term hair removal but are expensive.

Hirsutism is excessive growth of terminal hair in a typical male pattern in a female. It is typically a sign of excessive androgen levels. Hirsutism has been reported in 5% to 15% of women and is often associated with decreased quality of life and significant psychological stress.1–5 Hirsutism should be differentiated from hypertrichosis, which is increased growth—typically of vellus hair—in a generalized nonsexual distribution that is independent of androgens, although hyperandrogenism can exacerbate the condition.6

Physiology

Structurally, there are three types of hairs: lanugo, which is soft hair on the skin of the fetus that disappears in utero or in the first few weeks of life; vellus hairs, which are soft, small, and nonpigmented; and terminal hairs, which are longer, larger, coarser, and pigmented. The hair follicle cycles through three phases: anagen, a period of rapid growth; catagen, a period of involution; and telogen, a period of rest and shedding of hair.7 The duration of the anagen phase and rate of growth determine the length of hair and vary by type of hair and body region. The anagen cycle of facial hair is about four months; therefore, it takes about six months to note any change after an intervention and nine months to see maximal change.

Hair growth is influenced by several local and systemic factors, including cytokines, growth factors, and sex steroids.8 Hair type and distribution are dependent on androgens that cause transformation of vellus hairs to terminal hairs. Androgens affect hair growth broadly, and there are only a limited number of androgen-independent areas (e.g., eyelashes, eyebrows, some scalp follicles).9,10 Androgens have a paradoxical response on the face and scalp: stimulating beard growth and inhibiting scalp hair growth lead to androgenic alopecia (male pattern baldness). Thyroid hormones, insulin resistance, and specific genes also influence hair growth.

Diagnosis

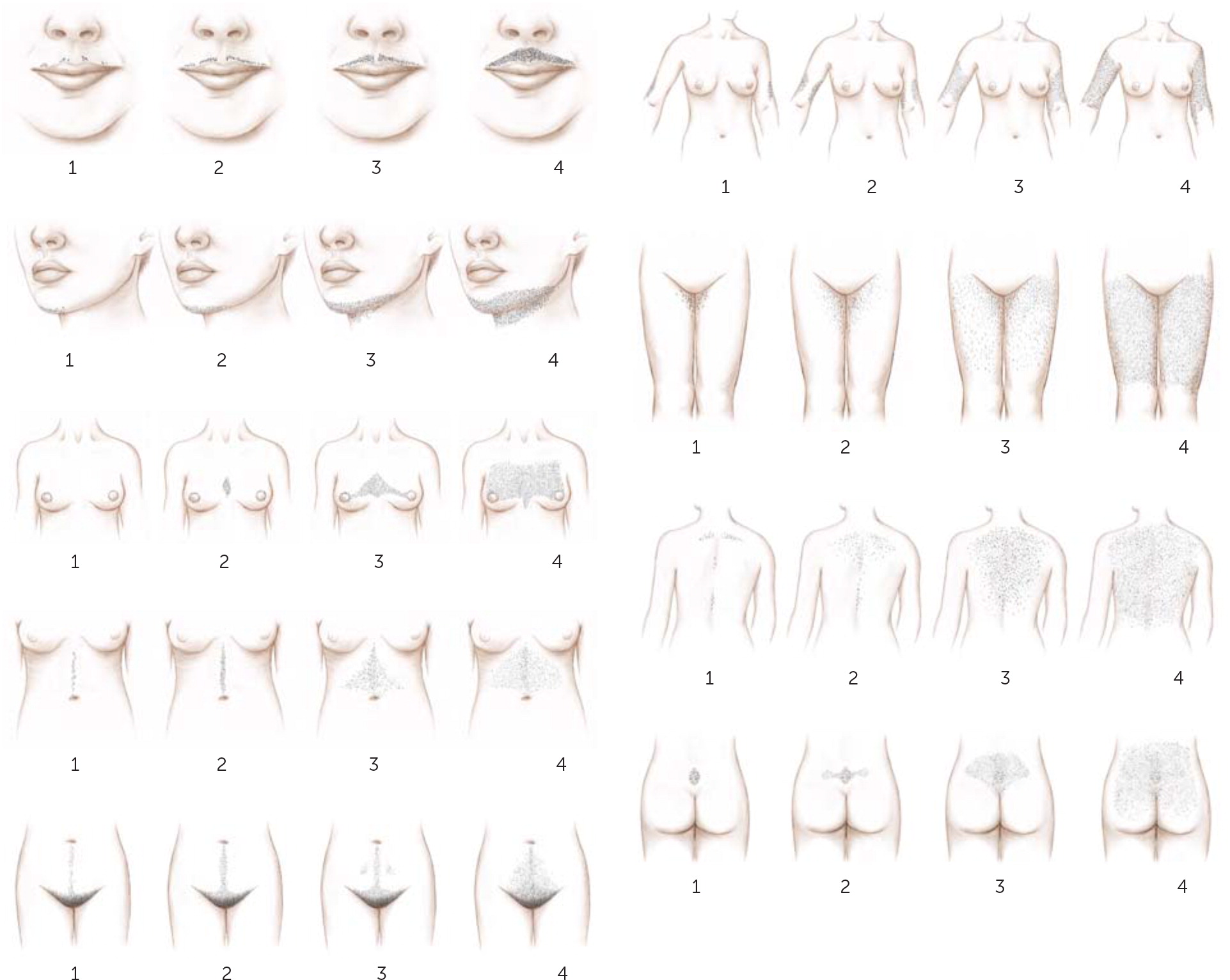

Hirsutism is a clinical diagnosis, and prevalence depends on the diagnostic criteria used. Hirsutism is commonly diagnosed using the modified Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system consisting of nine androgen-sensitive body areas11,12 (Figure 113). Cutoff scores vary by race and ethnicity: scores of 8 or greater are considered hirsutism in British and U.S. black and white women; 9 or greater in Mediterranean, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern women; 6 or greater in South American women; and 2 or greater in Asian women.6 Scores up to 15 indicate mild hirsutism, whereas those greater than 25 indicate severe hirsutism. Limitations of this scoring system include its subjective nature and inability to account for locally high scores or previous cosmetic treatments. The Endocrine Society recommends treating patient-important hirsutism, which is unwanted sexual hair growth of sufficient extent to cause patient distress.6

Causes

| Diagnosis | Percentage of cases | Historical and clinical clues |

|---|---|---|

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 71 | Acanthosis nigricans Acne Central obesity Infertility Insulin resistance Menstrual dysfunction Normal or slightly elevated androgen levels Polycystic ovary morphology on ultrasonography |

| Idiopathic hyperandrogenism | 15 | Elevated androgen levels No other secondary cause Normal menses Normal ovarian morphology on ultrasonography |

| Idiopathic hirsutism | 10 | No other secondary causes Normal androgen levels Normal menses Normal ovarian morphology on ultrasonography |

| Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia | 3 | Elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone level before and after corticotropin stimulation test Family history of adrenal hyperplasia High-risk ethnic group (e.g., Ashkenazi Jews, Hispanics, Slavic people) Infertility Menstrual dysfunction (including primary amenorrhea) |

| Androgen-secreting tumors | 0.3 | Elevated testosterone or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate level Palpable abdominal or pelvic mass Progression of hirsutism despite treatment Rapid onset of hirsutism Small masses may have indolent presentation Virilization (e.g., clitoromegaly, increased muscularity, deepened voice) |

| Iatrogenic hirsutism | Uncommon; prevalence not well defined | History of anabolic-androgenic steroid use Use of topical testosterone in a partner Use of valproic acid (Depakene) |

| Acromegaly | Rarely presents with isolated hirsutism | Coarse facial features Deepened voice Enlargement of nose and ears Frontal bossing Hyperhidrosis Increased hand and foot size Mandibular enlargement with increased interdental spacing |

| Cushing syndrome | Rarely presents with isolated hirsutism | Acne Central obesity Elevated 24-hour urinary free cortisol level Hypertension Impaired glucose tolerance Moon facies Proximal muscle weakness Purple skin striae |

| Hyperprolactinemia | Rarely presents with isolated hirsutism | Amenorrhea Galactorrhea Infertility |

| Thyroid disorders | Rarely present with isolated hirsutism | Menstrual dysfunction Thyroid dysfunction Hyperthyroidism: exophthalmos, goiter, heat intolerance, hyperactivity, palpitations, sleep disturbance, tremor, weight loss Hypothyroidism: cold intolerance, difficulty concentrating, dry skin, fatigue, hair loss, myxedema, weight gain |

POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of hirsutism, accounting for more than 70% of cases.14 PCOS is defined by the presence of at least two of the following criteria: chronic anovulation, clinical or biologic hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries.16 Additional symptoms include obesity, acne, alopecia, insulin resistance, infertility, and acanthosis nigricans. Androgen levels may be normal or mildly elevated. Hyperinsulinemia affects more than one-half of women with PCOS, triggering an increase in gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency. The subsequent increase in gonadotropin-releasing hormones triggers increased production of ovarian and adrenal androgens while the production of sex hormone–binding globulin in the liver decreases, resulting in an increased amount of biologically active free testosterone in the serum.15

IDIOPATHIC HYPERANDROGENISM

Idiopathic hyperandrogenism accounts for approximately 15% of hirsutism cases.14 It is characterized by normal menses, normal ovaries on ultrasonography, elevated androgen levels, and no secondary causes.

IDIOPATHIC HIRSUTISM

ADRENAL HYPERPLASIA

Adrenal hyperplasia is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern and is due to deficiency of one of the enzymes involved in adrenal steroid hormone synthesis, causing precursors to be shunted to the androgen pathway. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia is typically diagnosed at birth and is often associated with ambiguous genitalia and androgen excess. Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia is a milder form presenting in the peripubertal period with hirsutism and primary amenorrhea or infertility. The most common deficiency in people with nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia is 21-hydroxylase deficiency resulting in elevated levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone. Adrenal hyperplasia is more common in certain high-risk groups, such as Ashkenazi Jews, Hispanics, and Slavic people.18 Women with hirsutism who are at higher risk of adrenal hyperplasia because of their race or ethnicity should be screened by measuring early morning follicular phase 17-hydroxyprogesterone, even if serum total and free testosterone levels are normal.6

ANDROGEN-SECRETING TUMORS

Androgen-secreting tumors are a rare cause of hirsutism, can be ovarian or adrenal in origin, and are malignant in more than 50% of cases.6 The typical presentation is a more rapid onset of hirsutism (within a few months vs. several months to a year or more with other causes) with other androgenic findings or virilization (e.g., increased muscularity, deepening of the voice, breast atrophy, male pattern baldness, clitoromegaly). Small tumors can have more indolent presentations. The physical examination may reveal abdominal or pelvic masses; if they are adrenal in origin there will typically be associated hypercortisolemia and elevated dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels, leading to Cushing syndrome.

OTHER CAUSES

Other endocrine disorders such as hyperprolactinemia, thyroid disorders, acromegaly, and Cushing syndrome may be associated with hirsutism but rarely present with isolated hirsutism. Iatrogenic hirsutism can be caused by the use of certain medications, especially cyclosporine (Sandimmune), danazol, diazoxide, glucocorticoids, minoxidil, testosterone, and other anabolic steroids.19,20

Evaluation

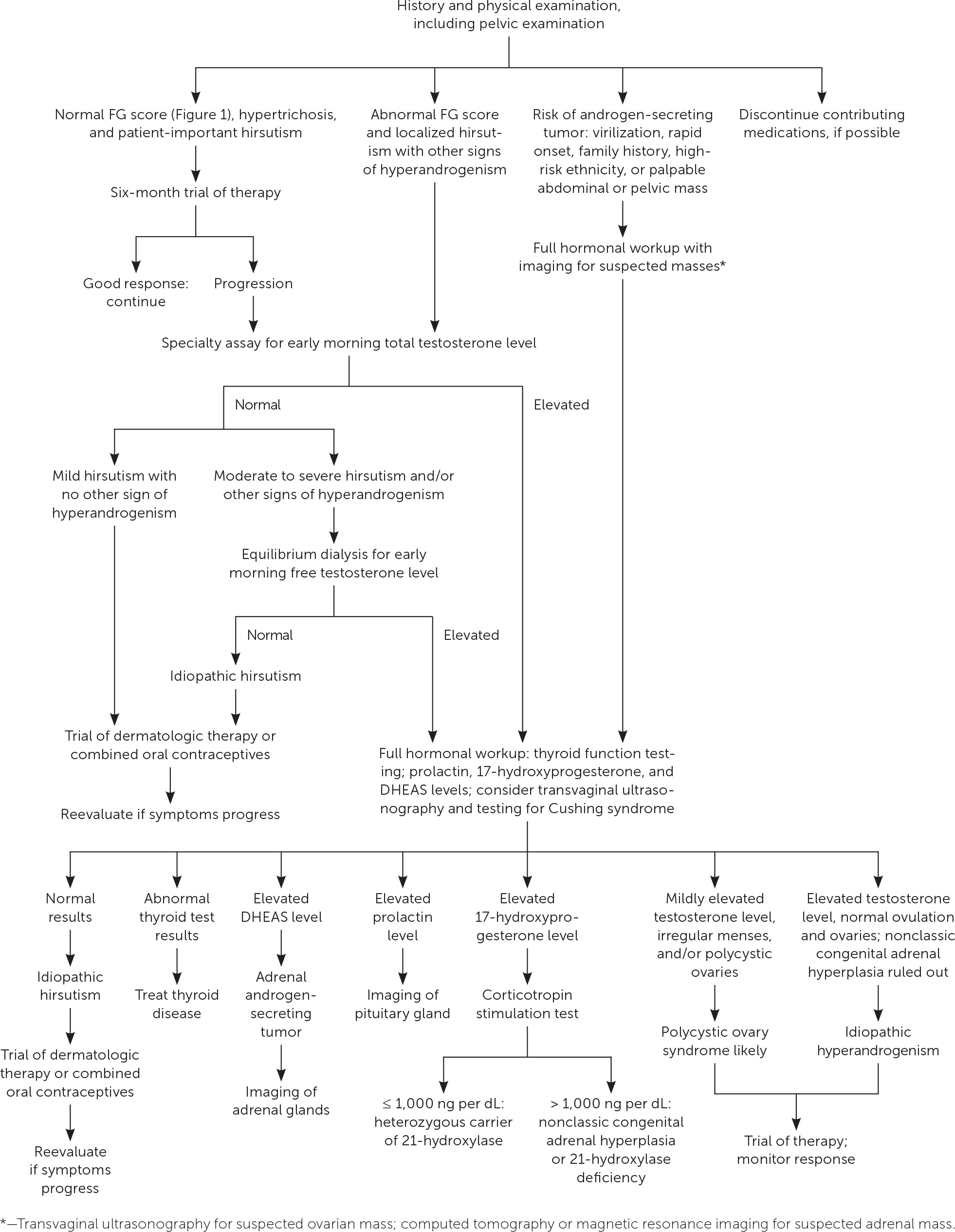

Hirsutism is most often due to benign conditions, although it can be a sign of an underlying hyperandrogenic disorder that requires specific treatment and has implications for reproduction, adverse health effects, or even life-threatening neoplasia.6 Figure 2 illustrates a suggested evaluation for hirsutism.6,13,14,21 A detailed history and physical examination are essential. The history should include family history of hyperandrogenism, menstrual history, description of the onset of hirsutism, androgenic medications (including topical use by a partner), and history of cosmetic treatments for hirsutism. The physical examination should include observation to determine the presence and degree of hirsutism and to detect signs suggestive of the specific etiology. A pelvic examination should be performed with close attention to signs of androgenization (e.g., clitoromegaly) or abdominal or pelvic masses.

Women with hirsutism and menstrual dysfunction, infertility, or any physical examination findings suggestive of endocrine disorders should undergo further hormonal workup.6 Rapid development of hirsutism, late onset, progression despite therapy, or signs of virilization may indicate an androgen-secreting tumor.14 In contrast, benign etiologies typically present with peripubertal onset, slow progression, family history of hyperandrogenism, and, rarely, signs of virilization.

Clinical practice guidelines suggest testing for elevated androgen levels in women with an abnormal hirsutism score.6,14,22 The degree of hirsutism does not necessarily correlate with the testosterone level. Free testosterone is the biologically active component of serum testosterone; however, there is considerable variability in measurements reported by various assays, particularly at low levels.22–24 Measurement of free testosterone is more accurate with equilibrium dialysis methods used by specialty laboratories. Unless this technique is available, the test is not reliable.

Other endocrine causes of hirsutism such as hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia can be excluded by serum thyroid studies and measurement of prolactin, which is particularly relevant in patients with other signs and symptoms consistent with these conditions. Women with hyperandrogenism or those with hirsutism who are at high risk (because of family history or race/ethnicity) warrant further workup with measurement of early morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone and DHEAS to screen for adrenal hyperandrogenism. Assessment for Cushing syndrome or acromegaly is warranted in women with features of these conditions. Pelvic ultrasonography is indicated to identify ovarian lesions in women with features suggestive of androgen-secreting tumors or to determine ovarian morphology.

Treatment

If bothersome hirsutism persists despite cosmetic measures (e.g., shaving, plucking, waxing), pharmacologic treatment should be initiated (Table 213,22,25–31), followed by direct hair removal methods if pharmacologic treatment does not yield satisfactory results.6 Pharmacologic therapy should be avoided if the patient is pregnant or trying to become pregnant. Lifestyle changes should be encouraged for patients with obesity, including those with PCOS. Referral to a dermatologist may be considered for intractable cases.

| Medication | Dosage | Adverse effects | Comments | U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined oral contraceptives | One tablet daily | Headache, nausea | First-line agents; may be used in combination with antiandrogens | Accidental use in pregnancy is low risk; may decrease lactation |

| Eflornithine (Vaniqa) | Apply topically twice daily | Acne, local irritation | Expensive | Safety risks unknown |

| Finasteride (Propecia) | 2.5 mg daily | Decreased libido | Additive benefit when used with spironolactone | High risk of feminization of male fetus |

| Glucocorticoids | Prednisone: 5 mg twice daily | Adrenal suppression, bone density loss, weight gain | Use in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia | Increased risk of growth retardation and cleft palate, especially if used in first trimester |

| Leuprolide (Lupron) | 3.75 mg intramuscularly monthly | Bone density loss, hot flashes, vaginal dryness | Consider using in conjunction with combined oral contraceptives | High risk of fetal harm |

| Spironolactone | 100 to 200 mg daily | Breast tenderness, hyperkalemia, irregular menses | Risk of breast adenomas in murine testing | Increased risk of spontaneous abortion and feminization of male fetus |

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Combined oral contraceptives should be used as initial therapy for hirsutism in women who are not trying to conceive.6,22,25,26,32 These drugs suppress luteinizing hormone secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production. They also stimulate production of sex hormone–binding globulin, thereby lowering serum free androgen levels. A recent meta-analysis showed that combined oral contraceptives decrease hirsutism scores, but because improvement in patient distress was not reported it is not known whether these differences are clinically meaningful.32 Low-androgen combined oral contraceptives containing desogestrel and drospirenone improved hirsutism scores slightly more than other formulations, but the difference was small and probably not clinically important.26

If combined oral contraceptives are contraindicated or ineffective, the antiandrogens spironolactone, finasteride (Propecia), or dutasteride (Avodart) may be considered.6,22,27,28,32,33 The antiandrogen flutamide should be avoided because of hepatotoxicity. Antiandrogens are teratogenic and must be avoided in pregnancy. They seem to confer an additive benefit when used with combined oral contraceptives. For women with classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency, glucocorticoids are effective for the treatment of hirsutism.13 However, they are much less effective in women with nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia and should be used only if trials of combined oral contraceptives and antiandrogen therapy are ineffective.29

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agnoists such as leuprolide (Lupron) have been beneficial in reducing hirsutism in patients with ovarian hyperandrogenism. However, they cause severe hypoestrogenism and bone loss, and their use is generally not recommended except in patients with severe hyperandrogenism, in whom combined oral contraceptives and antiandrogens are ineffective.6,34 Insulin-lowering medications such as metformin and pioglitazone (Actos) are widely used in the treatment of PCOS, but they are not effective for the treatment of hirsutism.6,30,32

The ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor eflornithine (Vaniqa) can be used as topical therapy for excessive facial hair. Patients should expect noticeable improvement in approximately six to eight weeks.35 Eflornithine is safe when combined with other therapies.

HAIR REMOVAL METHODS

Numerous hair removal methods may be used to treat hirsutism.6 Shaving is inexpensive and effective but must be done frequently. Chemical depilatory agents can be used to dissolve the hair but may irritate the skin and cause dermatitis. Epilation by plucking or waxing is also effective but is painful and can result in scarring, folliculitis, and hyperpigmentation.

If patients desire a more permanent solution, photoepilation or electrolysis can be considered.6 Although electrolysis is effective, it can also be painful, time consuming, and impractical for removing hair over large areas of skin. Because of these limitations, photoepilation has become the most popular procedure for long-term hair removal. Photoepilation destroys pigmented terminal hair follicles through thermal damage from one of four types of lasers, based on the patient's hair color and skin pigmentation. Photoepilation is not entirely effective; trials have shown hair reduction of 40% to 80%, depending on the type of laser used and the number of treatments provided.36 Despite its limitations, photoepilation is the preferred treatment for permanent hair removal. It is up to 60 times faster to perform than electrolysis and seems to be more effective in most patients. The exceptions are blonde and white-haired women, in whom electrolysis is a better option.21

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Bode, et al.,13 and by Hunter and Carek.37

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms hirsutism, hypertrichosis, hair removal, and polycystic ovarian syndrome. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Search date: March 16, 2018.