Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(1):73-78

Patient information: See related handout on costochondritis.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Costochondritis is a common cause of chest pain. It most commonly occurs in adults between 40 and 50 years of age, with a slight predominance in women. Although musculoskeletal and other chest wall conditions are the most common etiology for chest pain presenting to primary care, an initial differential diagnosis should include cardiovascular, psychogenic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and miscellaneous or unknown sources (more to less common, respectively). Additionally, physicians should remain vigilant throughout the workup because a notable portion of patients with chest wall tenderness to palpation may also have acute myocardial infarction. After a musculoskeletal or chest wall source is determined, differential diagnosis includes costochondritis, muscle trauma (including postoperative) or overuse, arthritis, fibromyalgia, neoplasm, infection, herpes zoster, Tietze syndrome, painful xyphoid syndrome, and slipping rib syndrome. The diagnosis of costochondritis is largely based on history and a physical examination that demonstrates reproduction of pain through palpation of the parasternal region of the chest wall, performance of a crowing rooster maneuver, and/or a crossed-chest adduction maneuver. Although high-quality evidence is lacking, treatment options include local application of heat, oral or topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, lidocaine patches, capsaicin cream, physical therapy, and acupuncture. Most patients will have complete resolution of symptoms in a few weeks' time with conservative therapy. Recalcitrant cases may respond to corticosteroid injections.

Costochondritis is a commonly encountered condition in primary care that is characterized by chest wall pain from inflammation in the costochondral joints. It most commonly occurs in adults 40 to 50 years of age. This article reviews the best available patient-oriented evidence for costochondritis.

Epidemiology

The most common age for costochondritis is middle age (between 40 and 50 years of age) with a slight predominance in women (69%) vs. men (56%).1–3

Chest pain in adolescents presenting to an outpatient clinic is most often diagnosed with a musculoskeletal etiology (31%), with costochondritis being diagnosed 13% of the time.3,4

Approximately 1% to 3% of all ambulatory visits in the primary care setting are for chest pain.5–11 Of these, chest wall pain accounts for 20% to 50%.1,5–12 Costochondritis in particular accounts for 6% to 13%.6,10,11

In emergency departments, chest pain accounts for 9% to 10% of visits, with musculoskeletal causes accounting for 15% to 45% of noncardiac chest pain.13–15

Diagnosis

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

| Diagnosis | Clinical findings | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction16 | Chest pain radiates to both arms | 7.1 | 0.67 |

| Third heart sound on auscultation | 3.2 | 0.88 | |

| Hypotension | 3.1 | 0.96 | |

| Acute thoracic aortic dissection17 | Acute chest or back pain and a pulse differential in the upper extremities | 5.3 | NA |

| Chest wall pain1 | At least two of the following findings: localized muscle tension, stinging pain, pain reproducible by palpation, absence of cough | 3.0 | 0.47 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease18,19 | Burning retrosternal pain, acid regurgitation, sour or bitter taste in the mouth; one-week trial of high-dose proton pump inhibitor relieves symptoms | 3.1 | 0.30 |

| Heart failure20 | Pulmonary edema on chest radiography | 11.0 | 0.48 |

| Clinical impression/judgment | 9.9 | 0.65 | |

| History of heart failure | 5.8 | 0.45 | |

| History of acute myocardial infarction | 3.1 | 0.69 | |

| Panic disorder/anxiety state21 | Ask a single question: In the past four weeks, have you had an anxiety attack (suddenly feeling fear or panic)? | 4.2 | 0.09 |

| Pericarditis22,23 | Clinical triad of pleuritic chest pain (increases with inspiration or when reclining and lessens by leaning forward), pericardial friction rub, and electrocardiographic changes (PR-interval depression, diffuse ST-segment elevation with concave downward appearance, and lack of T-wave inversion) | NA | NA |

| Pneumonia24,25,28 | Egophony (E to A change due to increased resonance and higher pitch of spoken words when auscultated over areas of lung consolidation) | 8.6 | 0.96 |

| Clinical impression | 7.7 | 0.54 | |

| Dullness to percussion | 4.3 | 0.79 | |

| Fever | 2.1 | 0.71 | |

| Pulmonary embolism26,27 | High pretest probability based on Wells criteria | 6.8 | 1.80 |

| Moderate pretest probability based on Wells criteria | 1.3* | 0.70 | |

| Low pretest probability based on Wells criteria | 0.1 | 7.60 |

| Condition | Diagnostic considerations | Treatment principles |

|---|---|---|

| Arthritis of sternoclavicular, sternomanubrial, or shoulder joints | Tenderness to palpation of specific joints of the sternum; evidence of joint sclerosis visible on radiography | Analgesics, intra-articular corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy 29,30 |

| Costochondritis | Tenderness to palpation of costochondral junctions; reproduces patient's pain; usually multiple sites on same side of chest31 | Simple analgesics; heat or ice; rarely, local anesthetic injections or corticosteroid injections29,30 |

| Destruction of costal cartilage by infections or neoplasm | Bacterial or fungal infections or metastatic neoplasms to costal cartilages; infections occur postsurgery or in intravenous drug users; chest computed tomography imaging useful to show alteration or destruction of cartilage and extension of masses to chest wall | Antibiotics or antifungal drugs; surgical resection of affected costal cartilage; treatment of neoplasm based on tissue type32,33 |

| Fibromyalgia | Symmetric tender points at second costochondral junctions, with characteristic tender points in the neck, back, hip, and extremities and widespread pain29,31 | Graded exercise is beneficial; cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), antidepressants, and pregabalin (Lyrica) may be beneficial34 |

| Herpes zoster of thorax | Clusters of vesicles on red bases that follow one or two dermatomes and do not cross the midline; usually preceded by a prodrome of pain; postherpetic neuralgia is potential complication that is more common in older patients35 | Oral antiviral agents (e.g., acyclovir, famciclovir [Famvir], valacyclovir [Valtrex]); analgesics as needed for pain; may require narcotics or topical lidocaine patches to control pain35 |

| Painful xiphoid syndrome | Tenderness at sternoxiphoid joint or over xiphoid process with palpation36 | Usually self-limited unless associated with congenital deformity of xiphoid; analgesics; rarely, corticosteroid injections36 |

| Slipping rib syndrome | Tenderness and hypermobility of anterior ends of lower costal cartilages causing pain at lower anterior chest wall or upper abdomen; diagnosis by “hooking maneuver”: curving fingers under costal margin and gently pulling anteriorly—a “click” and movement is felt that reproduces patient's pain31,37 | Rest, physiotherapy, intercostal nerve blocks; if chronic and severe, surgical removal of hypermobile cartilage segment31 |

| Tietze syndrome | Single tender and swollen, but nonsuppurative, costochondral junction, usually in costochondral junction of ribs two and three31,37 | Simple analgesics; usually self-limiting; rarely, corticosteroid injections29,31 |

| Traumatic muscle pain and overuse myalgia | History of trauma to chest or recent new onset of strenuous exercise to upper body (e.g., rowing); may be bilateral and affecting multiple costochondral areas; muscle groups may also be tender to palpation31 | Simple analgesics; refrain from doing or reduce intensity of strenuous activities that provoke pain29,31 |

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The typical presentation of costochondritis is bilateral parasternal chest wall pain exacerbated by deep breaths, coughing, and stretching.

The upper (predominantly second through fifth) costochondral and/or costosternal junctions are most commonly involved.2,3,31,38

The areas of tenderness are not generally accompanied by heat, erythema, or localized swelling.2,3,31,38,39

Tietze syndrome presents similarly to costochondritis but includes visible edema at the involved joint(s), typically is unilateral involving the second rib, and is often incited by infection or trauma.3,31,40

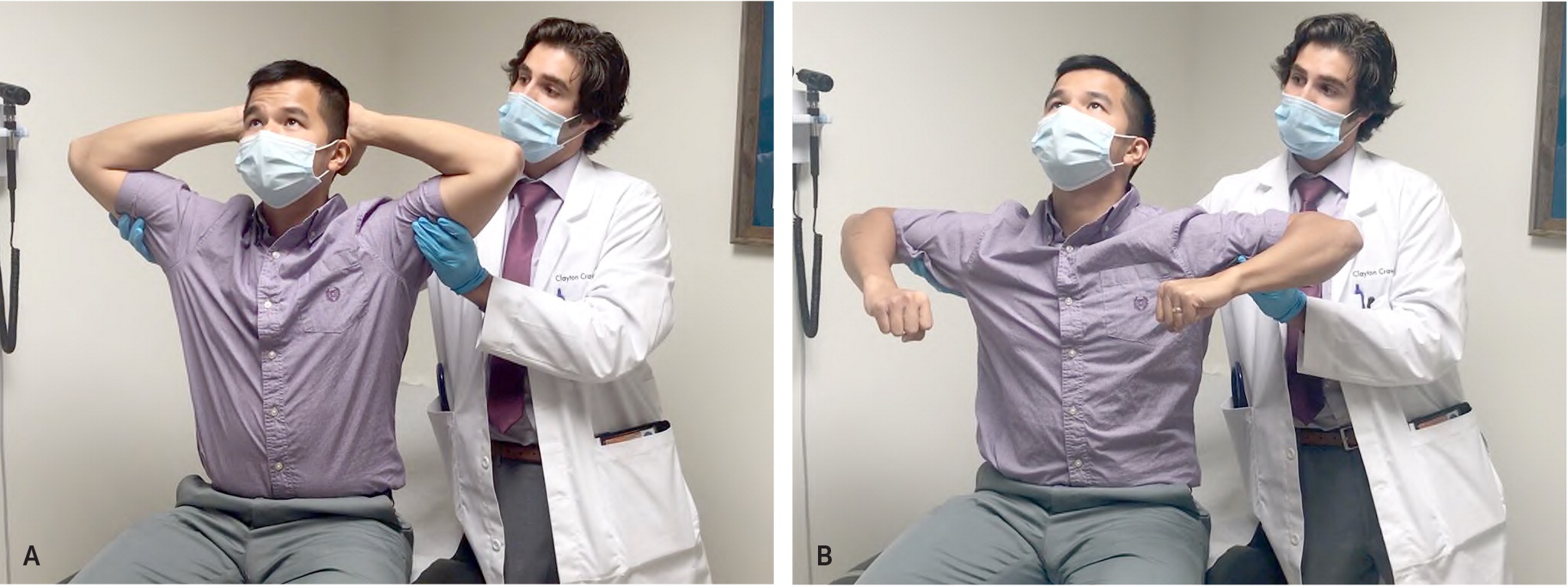

Pain reproduced by the following maneuvers has classically proven helpful: direct palpation to the involved costosternal or costochondral junction; the crowing rooster maneuver (patient neck extension simultaneously accompanied by the physician placing posterior and superior traction on the patient's arms from behind [Figure 1; also see a video showing the crowing rooster maneuver); and crossed-chest adduction of the ipsilateral arm combined with neck rotation toward the ipsilateral shoulder41 (Figure 2; also see a video showing the crossed-chest adduction maneuver).

A study of primary care patients with chest pain found that pain reproducible by palpation, no history of coronary heart disease, pain that is neither retrosternal nor oppressive, the physician not being concerned about the cause of chest pain, pain being well-localized by history or physical examination, and stabbing pain were all independent predictors of chest wall syndrome as the cause of chest pain (Table 3).42

Crowing Rooster Maneuver

Crossed-Chest Adduction Maneuver

| Independent predictors of chest wall syndrome | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) for association with chest wall syndrome | Points | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palpation reproduces pain | 6.5 (4.6 to 9.1) | 2 | |

| No history of coronary artery disease | 5.1 (2.9 to 9.1) | 1 | |

| Absence of physician's concern | 5.0 (2.8 to 8.8) | 1 | |

| Pain not retrosternal or oppressive | 3.1 (2.2 to 4.3) | 1 | |

| Pain well localized by history and/or physical examination | 3.1 (2.2 to 4.4) | 1 | |

| Pain stabbing in nature | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.2) | 1 | |

| Total:___ | |||

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Because the clinical examination lacks specificity, most patients with chest pain still need a thorough evaluation, including electrocardiography at a minimum, to rule out other more serious causes.1,3,6–16,43

In one study, 12% of patients presenting to an emergency department with a chief symptom of chest pain and noted to have chest wall tenderness also had an acute myocardial infarction.2

Validated clinical prediction rules have proven useful in assisting with cardiac risk stratification of patients presenting to primary care and the emergency department with chest pain, but they should not completely replace clinical judgment.1,12,43–45

There are no laboratory tests, imaging tests, or electrocardiography findings specifically for the diagnosis of costochondritis. If a patient relates a history of dyspnea or chest wall trauma, a chest radiograph or rib series may be indicated; in adolescent patients with low risk for coronary disease, electrocardiography may be unwarranted. Any diagnostics performed should be directed toward ruling out other possible etiologies based on each patient's unique differential diagnosis.

Treatment

PHYSICAL MODALITIES

A targeted stretching program under the direction of a physical therapist demonstrated a small reduction in pain among a group of patients who had symptoms for more than one year.47

Local application of heat is often recommended but lacks evidence from clinical trials. A period of rest from activities that exacerbate pain is often recommended.31

DRUG THERAPY

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the most commonly prescribed medications, although no clinical trials have evaluated their effectiveness. Additionally, higher dosages and frequency of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate gastritis or reflux, further complicating the clinical diagnosis.

Capsaicin, diclofenac gel, and lidocaine patches have been recommended primarily based on experience with other inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions.48

ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

Acupuncture has been used for treatment, but no randomized, controlled studies for effectiveness are available.49

OTHER TREATMENT

In one small prospective observational study, localized ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection at the affected costochondral junction resulted in clinical and sonographic improvements among the convenience-sampled group of nine patients with Tietze syndrome, which had not improved with conservative treatment after at least three months.50 There is inadequate evidence supporting corticosteroid injection specifically for costochondritis, so it should be considered only for patients whose symptoms do not improve with traditional therapies.

Prognosis

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Proulx and Zryd.3

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms costochondritis, chest pain, chest wall pain, and Tietze's syndrome. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, Clinical Evidence, Google Scholar, Trip Database, and the Cochrane database. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also searched. Search dates: January 2020, March 2020, and January 2021.

Assessment of range of motion and joint laxity