This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(4):388-396

Related Letter to the Editor: Long-Acting Injectable Clozapine Not Available in the United States

Patient information: See related handout on schizophrenia.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Schizophrenia is the most common psychotic mental disorder, and those affected have two to four times higher mortality than the general population. Genetic and environmental factors increase the risk of developing schizophrenia, and substance use disorder (particularly cannabis) may have the strongest link. Schizophrenia typically develops in young adulthood and is characterized by the presence of positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech. Negative symptoms include blunted affect, alogia, avolition, asociality, and anhedonia. Symptoms must be present for at least six months and be severe for at least one month to make a diagnosis. Because schizophrenia is debilitating, it should be treated with antipsychotics, and early treatment decreases long-term disability. Treatment should be individualized, and monitoring for effectiveness and adverse effects is important. Patients with a first episode of psychosis who receive a formal diagnosis of schizophrenia should be treated in a coordinated specialty care program. Second-generation antipsychotics are the preferred first-line treatment because they cause fewer extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients with schizophrenia who are treated with second-generation antipsychotics are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and should receive at least annual metabolic screening and counseling with interventions to prevent weight gain and encourage smoking cessation. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia should be treated with clozapine. Adjunctive treatments include electroconvulsive therapy, antidepressants, and cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis. Family and social support are keys to improved outcomes.

Schizophrenia is the most common psychotic mental disorder in the United States. It affects approximately 1% of the population and accounts for up to $23 billion in U.S. health care expenditures.1 Black people have disproportionately higher rates of being diagnosed with schizophrenia compared with non-Latino White people, which may be because of physician bias, less access to health care, and underdiagnosis of other psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar depression.2–4 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., men tend to have a syndromic phase between 18 and 25 years of age.5 In women, there are two peaks of syndromic presentation, the first between 25 years of age and mid-30s, and the second after 40 years of age.5 Initial presentation before 15 years of age is possible but rare.5 Medication adherence is associated with decreased risk of relapse into active-phase schizophrenia.6 Primary care physicians should be aware that patients with schizophrenia have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease as well as overall mortality.7

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not prescribe antipsychotic medications to patients for any indication without appropriate initial evaluation and ongoing monitoring. | American Psychiatric Association |

| Do not routinely prescribe two or more antipsychotic medications concurrently. | American Psychiatric Association |

Pathophysiology

The pathways associated with the development of psychotic symptoms involve altered neurotransmission of glutamate, serotonin, and dopamine in the hippocampus, midbrain, corpus striatum, and prefrontal cortex.8 Although the pathogenesis is unclear, proinflammatory cytokines may play a role in the development of schizophrenia and have recently prompted an interest in the therapeutic use of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents.9 Disrupted neural function during adolescent development and subcortical dopamine dysregulation are the neuromolecular processes that may account for symptoms ranging from cognitive deficits to psychosis.10

Etiology

The development of schizophrenia is best understood as a multifactorial process involving the interaction of genetic predisposition and environmental factors, also known as the polygenic threshold model.11 Epidemiologic studies suggest a hereditary pathogenesis for psychotic disorders, with higher rates in siblings and parents with a psychotic disorder and a 50% concordance of genetic loci between identical twins.8

Environmental factors that increase the risk of schizophrenia during fetal development and early life include infections (e.g., rubella, influenza, Toxoplasma gondii, herpes simplex virus type 2), and nutritional deficiencies (e.g., folic acid, iron, vitamin D).12 Pregnancy and birth complications, specifically neonatal hypoxic events, appear to be significant risk factors for the development of schizophrenia.13 Other observed risk factors include cannabis use, childhood trauma, and socioeconomic status.12 These risk factors work at the epigenetic level to show genetic and inflammatory predispositions.

A large longitudinal prospective study of adolescents in New Zealand showed a relationship between cannabis use and the development of schizophrenia.14 A meta-analysis that studied the association between the degree of cannabis consumption and psychosis revealed an odds ratio of 3.90 (95% CI, 2.84 to 5.34) for the risk of schizophrenia in the heaviest cannabis users compared with nonusers, with a dose-response relationship between all levels of use and the risk for psychosis.15 It is hypothesized that the release of dopamine resulting from excess stimulation of cannabinoid receptor 1 can at least partially trigger schizophrenia in genetically predisposed individuals.12 Other studies have suggested a strong association between substance use disorder and risk of developing or exacerbating symptoms of schizophrenia.16,17 When primary care physicians are screening for substance use disorders in adolescents, they should discuss the association of cannabis use with schizophrenia, especially when a family history or other identifiable risk factors are present.

Clinical Presentation

It is important to identify schizophrenia early in the course of disease because those who are treated early have better long-term outcomes.12 There are no biomarkers or neuroimaging tests that aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia.8,12 Therefore, primary care physicians must be vigilant in identifying those with psychotic symptoms, using current diagnostic criteria as well as specialty care referral to aid in diagnosis.

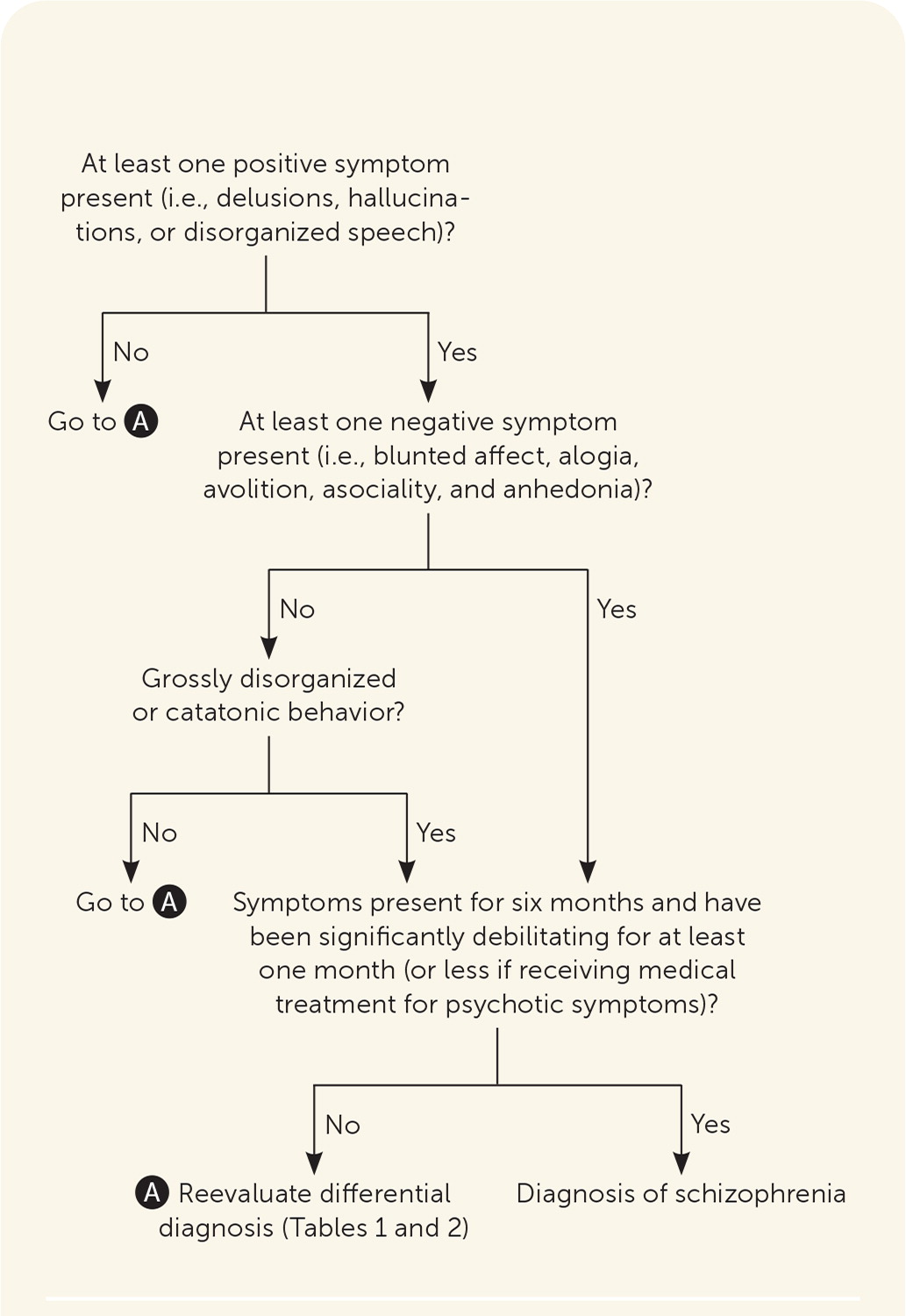

Schizophrenia is characterized by two sets of categorical symptoms, with at least one positive symptom and either one negative symptom or grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior present for at least six months. Positive symptoms include bizarre or confused behavior with hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech.5 Negative symptoms comprise a lack of normal function and include blunted affect, alogia (i.e., reduction in quantity of words spoken), avolition (i.e., reduced goal-directed activity due to decreased motivation), asociality, and anhedonia.5 Symptoms must be present for at least six months and be severe for at least one month (or less if receiving clinical treatment), and must be significantly debilitating to a person's level of functioning, although milder symptoms are usually present throughout the six-month period.5 Other psychiatric disorders and medical conditions that should be ruled out when patients present with symptoms are reviewed in Table 118,19 and Table 2.18 Primary care physicians can use Figure 1 to assist with the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

| Psychiatric condition | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|

| Bipolar disorder with psychotic features | Psychotic symptoms during manic or depressive episodes |

| Brief psychotic disorder | Delusions, hallucinations, and other psychotic symptoms lasting more than one day but less than one month |

| Delusional disorder | Fixation on false beliefs or nonbizarre delusions without other psychotic symptoms |

| Major depressive disorder with psychotic features | Psychotic symptoms with mood disturbances qualifying for concomitant major depressive disorder diagnosis |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Significant obsessions, compulsions, and preoccupations |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | Symptoms related to reliving inciting traumatic event |

| Schizoaffective disorder | Mania or depression occurring concomitantly with psychotic symptoms; psychotic symptoms without mood disturbance |

| Schizophreniform disorder | Psychotic symptoms lasting at least one month, but less than six months |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | No hallucinations or delusions with personality features |

| Medical condition | Distinguishing features | Laboratory findings |

|---|---|---|

| Cushing syndrome | Abdominal striae, easily bruised, fat pads around shoulders, hirsutism, round face | Elevated 24-hour urine cortisol level |

| Delirium | Confused thinking and reduced awareness of surrounding environment | — |

| Dementia | Cognitive and memory deficits | — |

| Intracranial tumor | Focal neurologic deficits | Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain detecting a lesion |

| Paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic autoimmune syndromes with psychosis | Memory problems, seizures | N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antibodies, anti-metabotropic glutamate antibodies, presence of ovarian teratoma on ultrasonography, abnormal electroencephalography, anti-Hu antibodies |

| Porphyria | Proximal muscle weakness, severe abdominal pain, tachycardia | Hyponatremia, elevated urine porphobilinogen |

| Substance abuse | Abnormal vital signs, needle marks, poor nutrition | Positive results on urine drug screen, elevated blood alcohol level |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Alopecia, discoid rash, fever, malar rash, oral ulcers, pleural or pericardial friction rub | Anemia, elevated antinuclear antibodies titer, pleural effusion on chest radiography, proteinuria, low complements; presence of anti-Smith antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, anti-double stranded DNA, anticardiolipin or anti-beta2-glycoprotein antibodies |

| Thyroid disorders | Coarse hair, dry skin, exophthalmos, tachycardia or bradycardia | Abnormal thyroid-stimulating hormone level |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | Ataxia, atrophic glossitis, memory impairment, muscle weakness | Low serum vitamin B12, macrocytic anemia, and indirect bilirubin levels |

| Wilson disease | Ataxia, dysarthria, hepatomegaly, hyper-reflexia, jaundice, Kayser-Fleischer rings in the cornea | Basal ganglia lesions on magnetic resonance imaging, Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes |

The natural course of schizophrenia can be divided into four stages: premorbid, prodromal, syndrome, and chronic/residual. During the premorbid and prodromal stages, which typically encompass ages between birth and early 20s, people with schizophrenia may have no symptoms. Although early detection and intervention are ideal for improved outcomes, a lack of sensitive and specific diagnostic criteria for premorbid and prodromal schizophrenia is a known barrier that can hinder the implementation of proven therapeutic strategies.20

Once in the syndromic phase, patients will meet the criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia. The severity of the disease during the chronic/residual stage will be impacted by social and medical factors such as a social support system and adherence to maintenance therapy to avoid relapses.12

Treatment

The primary goal for initial treatment of schizophrenia should be to reduce acute positive symptoms by using first-or second-generation antipsychotics (Table 320–29), allowing the patient to return to a baseline level of function and prevent long-term disability. Treatment for schizophrenia should continue for life.30

| Medication | Initial dosage (mg per day) | Typical dosage range (mg per day) | Common adverse effects | Serious adverse effects | Comments | Cost* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation antipsychotics | ||||||||

| Chlorpromazine | 25 to 100 | 200 to 800 | Dry mouth, elevated prolactin levels, extrapyramidal symptoms, glucose intolerance, postural hypotension, somnolence, weight gain | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | Has the most anticholinergic effects of the first-generation antipsychotics | $25 for 30 25-mg tablets | ||

| Fluphenazine | 2.5 to 10 | 6 to 20 | Akathisia, parkinsonism, dystonia, hyperprolactinemia | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | — | $20 for 30 2.5-mg tablets | ||

| Haloperidol | 1 to 15 | 5 to 20 | Dry mouth, extrapyramidal symptoms, galactorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, hypotension, somnolence, tachycardia | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, prolonged QT syndrome | — | $6 for 30 1-mg tablets | ||

| Loxapine | 20 | 60 to 100 | Dry mouth, extrapyramidal symptoms, galactorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, hypotension, somnolence, tachycardia | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | — | $20 for 60 10-mg capsules | ||

| Perphenazine | 8 to 16 | 8 to 32 | Dry mouth, extrapyramidal symptoms, galactorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, hypotension, somnolence, tachycardia | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | — | $16 for 30 8-mg tablets | ||

| Second-generation antipsychotics | ||||||||

| Aripiprazole (Abilify) | 10 to 15 | 10 to 15 | Anxiety, constipation, dizziness, headache, insomnia | Agranulocytosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | May reduce hyperprolactinemia when used with other antipsychotics; does not impact lipids as much as other second-generation antipsychotics21 | $10 ($580) for 30 10-mg tablets | ||

| Brexpiprazole (Rexulti) | 1 | 2 to 4 | Hyperlipidemia, weight gain, akathisia, somnolence | QT prolongation | — | $— ($1,300) for 30 1-mg tablets | ||

| Cariprazine (Vraylar) | 1.5 | 1.5 to 6 | Hyperprolactinemia, weight gain, somnolence | QT prolongation | — | $— ($1,300) for 30 1.5-mg capsules | ||

| Clozapine (Clozaril) | 12.5 to 25 | 300 to 450 | Hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, orthostasis, seizures | Agranulocytosis (complete blood count should be obtained weekly for six months, then every two weeks for six months, then monthly), seizures, tardive dyskinesia, myocarditis | Primarily for treatment of severe refractory schizophrenia | $7 ($65) for 10 25-mg tablets | ||

| Lurasidone (Latuda) | 40 | 40 to 160 | Hyperlipidemia, diabetes, parkinsonism, somnolence, nausea | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, QT prolongation | — | $— ($1,400) for 30 40-mg tablets | ||

| Olanzapine (Zyprexa) | 5 to 10 | 10 to 20 | Weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, akathisia, hyperprolactinemia, postural hypotension | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | Do not use with benzodiazepines Patients who smoke may need a dose increase of 30% because of increased metabolism Increased incidence of weight gain compared with other second-generation antipsychotics20 | $5 ($460) for 30 5-mg tablets | ||

| Paliperidone ER (Invega) | 6 | 3 to 12 | Hyperprolactinemia, hyperlipidemia, weight gain, priapism | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | Is the active metabolite of risperidone | $90 ($370) for 30 6-mg tablets | ||

| Quetiapine (Seroquel) | Immediate release: 50 Extended release: 300 | 400 to 800 | Hyperlipidemia, agitation, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, somnolence, weight gain | Agranulocytosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | Elevated discontinuation rate compared with other second-generation antipsychotics22 | $4 ($200) for 30 50-mg tablets $7 ($500) for 30 300-mg tablets | ||

| Risperidone (Risperdal) | 2 | 2 to 8 | Anxiety, hyperprolactinemia, hypotension, insomnia, metabolic changes, nausea, weight gain | Agranulocytosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | Higher incidence of increased prolactin levels and extrapyramidal effects than other second-generation antipsychotics | $3 ($250) for 30 2-mg tablets | ||

| Ziprasidone (Geodon) | 40 | 80 to 160 | Agitation, hypotension, metabolic changes, nausea, somnolence, tachycardia, weight gain | Agranulocytosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia | Least amount of weight gain compared with other atypical antipsychotics | $8 ($600) for 30 40-mg capsules | ||

A GENERAL APPROACH TO THE PATIENT

There is no reliable strategy or data to predict how a patient with schizophrenia will respond to medication or the patient's risk of adverse effects. Factors that impact selection of medication include individual preference, prior treatment response, adherence history, relevant medical history and risk factors, adverse effects, and long-term treatment planning, including cost and access to medication.23

Primary care physicians should begin by prescribing an antipsychotic with a favorable adverse effect profile that is cost-effective, while establishing long-term treatment or referring the patient to a specialist. The U.K.-based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that primary care physicians consult a psychiatrist and immediately refer the patient to mental health services when prescribing antipsychotic medications for psychotic symptoms.32 Primary care physicians who are comfortable prescribing antipsychotics can play a vital role in treating patients in resource-constrained environments. A therapeutic relationship that promotes medication adherence while coordinating with social services that help address social determinants of health (e.g., living situation, employment, drug use) can reduce psychiatric hospitalizations.33

FIRST- AND SECOND-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS

First-generation antipsychotics are dopamine receptor antagonists. Second-generation antipsychotics are serotonin receptor antagonists, which have less impact on dopamine metabolism. There is no evidence-based algorithm or ranking guidance in selecting a first- or second-generation antipsychotic because of the heterogeneity of clinical trials and limited number of head-to-head comparisons.20 Second-generation antipsychotics are generally preferred as first-line agents for acute treatment and maintenance therapy because of their reduced risk of extrapyramidal symptoms compared with first-generation antipsychotics.34 However, second-generation antipsychotics still carry a significant risk of extrapyramidal symptoms.

Both generations of antipsychotics can produce extrapyramidal symptoms of pseudoparkinsonism, akathisia (i.e., a sensation of inner restlessness and inability to be still), and dystonia. First-generation antipsychotics, which are comprised of typical antipsychotics phenothiazines (e.g., chlorpromazine), thioxanthenes (e.g., thiothixene), and butyrophenones (e.g., haloperidol), are more likely than second-generation antipsychotics to contribute to developing these conditions. Antihistamines, nonselective beta blockers, or benzodiazepines are used to treat symptoms.20

Tardive dyskinesia, characterized by repetitive, jerking movements that occur in the face, neck, and tongue, is another adverse effect of first- and second-generation antipsychotics. It is more common in older female patients with diabetes mellitus.35 Moderate to severe tardive dyskinesia should be treated with reversible vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors, deutetrabenazine (Austedo) and valbenazine (Ingrezza; only available through specialty pharmacies).36 The most common adverse effect is somnolence. Patients should be monitored for QT-prolongation. Vitamin E, vitamin B6, and amantadine may reduce symptoms of tardive dyskinesia.37

Second-generation antipsychotics, also known as atypical antipsychotics, are associated with the development of metabolic syndrome, which includes weight gain, hyperglycemia with the potential of developing insulin resistance, and lipid abnormalities.38,39 A meta-analysis found a significant reduction in body mass index and insulin resistance, but not fasting blood glucose levels, in patients taking a second-generation antipsychotic with metformin compared with taking the antipsychotic with placebo.40 Another meta-analysis determined that metformin compared with placebo achieved clinically relevant weight loss of 7% of body weight (number needed to treat [NNT] = 3).41 A new combination formulation of olanzapine/samidorphan (Lybalvi) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and was associated with significantly less weight gain and smaller increases in waist circumference than olanzapine (Zyprexa) alone.42 There are no head-to-head studies that compare the efficacy of samidorphan (an opioid receptor antagonist) with metformin to justify the cost associated with the new combination medication.

TREATMENT-RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA

Treatment-resistant schizophrenia is the persistence of significant symptoms despite adequate pharmacologic treatment.26 To determine severity of symptoms and response to treatment, physicians can use validated scoring scales (Table 4).26,43 Higher scores are indicative of treatment-resistant schizophrenia and should encourage a goal-oriented discussion of escalation of therapy and evaluation of psychosocial interventions. The scales should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) |

| https://www.smchealth.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/bprsform.pdf?1497977629 |

| Clinical Global Impression Schizophrenia (CGI-SCH) |

| https://medworksmedia.com/product/clinical-global-impressions-cgi/ |

| Negative Symptom Assessment-16 (NSA-16) |

| https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/negative-symptom-assessment |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale 6- or 30-item version (PANSS-6 or PANSS-30) |

| https://nationalepinet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/PANSS-6_8-3-20.pdf |

| https://www.sandiego.edu/teamup/documents/DRL-PANSS.pdf |

| Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) |

| https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/GetPdf.cgi?id=phd000807.2 |

| Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) |

| https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/GetPdf.cgi?id=phd000837.1 |

Schizophrenia refractory to first- and second-generation antipsychotics should be treated with clozapine (Clozaril).20,44 In a meta-analysis comparing first- and second-generation antipsychotics with clozapine, higher rates in symptom reduction were shown with clozapine over a three-month period (NNT = 9).44 Individuals receiving treatment with clozapine had a higher likelihood of experiencing sialorrhea (number needed to harm [NNH] = 4), seizures (NNH = 17), tachycardia (NNH = 17), and dizziness (NNH = 11).44

In the United States, clozapine has an FDA boxed warning highlighting the risk of severe neutropenia (e.g., agranulocytosis), myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, seizures, and profound hypotension. Clozapine requires additional training and enrollment in the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program (https://www.newclozapinerems.com/home#) [corrected].20

Schizophrenia is not treatment resistant if patients are receiving subtherapeutic doses of antipsychotics due to lack of adherence to their treatment regimen. Long-acting injectables increase adherence to therapy.45 In a meta-analysis comparing oral therapy with long-acting injectable therapy, patients taking long-acting injectables were found to have reduced hospitalizations in their lifetime (NNT = 6) and decreased rates of discontinuation from therapy (NNT = 10).46

ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENTS

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that adjunctive electroconvulsive therapy in addition to clozapine for four to 12 weeks was superior to clozapine monotherapy in providing symptom improvement in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (NNT = 3).47 However, electroconvulsive therapy was associated with memory impairment (NNH = 4) and headache (NNH = 8).

In a systematic review that analyzed psychosocial interventions, including cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis, psychoeducation, supported employment services, assertive community care, and family interventions, treatment was associated with improved functional outcomes measured as the ability to function in social and occupational settings.24 Relapse was reduced with family interventions, psychoeducation, illness self-management, and early interventions following a first episode of psychosis.24 A systematic review and meta-analysis found that cognitive remediation implemented by a trained therapist in conjunction with a structured development of cognitive strategies and integration with rehabilitation was effective in improving cognition and functioning.48 The American Psychiatric Association recommends that patients with a first episode of psychosis who receive a formal diagnosis of schizophrenia should be treated in a coordinated specialty care program.20,24

Prognosis

The clinical course and prognosis of people with schizophrenia are marked with heterogeneity with variations in remission and exacerbations, making the disease course unpredictable. People with schizophrenia have mortality rates two to four times greater than the general population.49 Factors contributing to increased mortality include concomitant psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, and suicide.50 However, most deaths are related to an increased rate of cardiovascular disease with concomitant renal disease, respiratory diseases, stroke, cancer, and thromboembolic events.50 People with schizophrenia should be screened by a primary care physician for cardiovascular disease and receive at least annual metabolic screening and counseling with interventions to prevent weight gain and attempt to mitigate other factors that could contribute to their overall health, such as smoking. People with schizophrenia who smoke cigarettes should be offered cessation therapy to achieve abstinence.23 A meta-analysis found that varenicline (Chantix) was superior to bupropion (Zyban) for tobacco cessation, but no significant difference was found between varenicline or bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy.51

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Schultz, et al.,54 and Holder and Wayhs.18

Data Sources: We were provided a search from Essential Evidence Plus using the search term schizophrenia. We searched the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Cochrane database, OVID, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. A PubMed search was completed using the search terms schizophrenia, schizophrenia diagnosis, schizophrenia treatment, antipsychotics, schizophrenia prognosis, tardive dyskinesia, and schizophrenia mortality. Search dates: October 2021, December 2021, April 2022, and August 2022.

This manuscript represents the work of the authors. Opinions herein do not represent the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Department of Defense, or the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.