Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(4):893-906

Inguinal and femoral hernias are the most common conditions for which primary care physicians refer patients for surgical management. Hernias usually present as swelling accompanied by pain or a dragging sensation in the groin. Most hernias can be diagnosed based on the history and clinical examination, but ultrasonography may be useful in differentiating a hernia from other causes of groin swelling. Surgical repair is usually advised because of the danger of incarceration and strangulation, particularly with femoral hernias. Three major types of open repair are currently used, and laparoscopic techniques are also employed. The choice of technique depends on several factors, including the type of hernia, anesthetic considerations, cost, period of postoperative disability and the surgeon's expertise. Following initial herniorrhaphy, complication and recurrence rates are generally low. Laparoscopic techniques make it possible for patients to return to normal activities more quickly, but they are more costly than open procedures. In addition, they require general anesthesia, and the long-term hernia recurrence rate with these procedures is unknown.

Inguinal and femoral hernias are the most common problems primary care physicians encounter that require surgical intervention. The treatment of these hernias costs approximately $3.5 billion every year.1 Untreated or recurrent inguinal hernias are responsible for an incalculable loss of productivity and revenue. Postoperative convalescence also contributes to absence from the work force.

A clear understanding of the epidemiology and anatomy of inguinal hernias provides a solid foundation for timely diagnosis and care. Since inguinal herniorrhaphy can be performed using a variety of techniques, the approach can be individualized. This article reviews the available surgical options for herniorrhaphy and the possible complications of these procedures.

Epidemiology

In the United States, approximately 96 percent of groin hernias are inguinal and 4 percent are femoral. Inguinal hernias are bilateral in as many as 20 percent of affected adults.1

The most common hernia in both sexes is the indirect inguinal hernia. The male-to-female ratio is 9:1 for inguinal hernias and 1:3 for femoral hernias. While inguinal hernias occur fairly equally across adult age groups, femoral hernias tend to occur more often in elderly women. The lifetime risk of inguinal herniation is approximately 10 percent.1

Anatomy of Groin Hernias

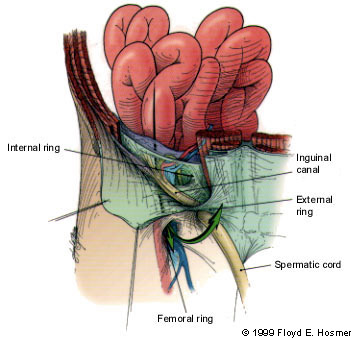

Inguinal hernias are broadly classified as indirect or direct, designations that refer to the relation of the herniation to the inferior epigastric arteries on the abdominal wall and the Hesselbach's triangle. The anatomic region known as Hesselbach's triangle is defined laterally by the inferior epigastric artery, medially by the lateral border of the rectus muscle and inferiorly by the inguinal ligament (Figure 1). An indirect hernia passes lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels and thus is outside of Hesselbach's triangle (Figure 2), while a direct hernia is medial to the epigastric vessels and therefore within the confines of this space (Figure 3).

An indirect hernia is generally believed to have a congenital component. The development of this type of hernia requires a potential hernia sac, which is provided by the processus vaginalis. After the fetal testis has descended into the scrotum from the retroperitoneum, the processus vaginalis normally obliterates, thereby removing this potential for herniation. Thus, an indirect hernia is the result of two conditions: (1) the existence of a potential space due to nonobliteration of the processus vaginalis and (2) a weakening of the fascia of the transversalis muscle fibers surrounding the exit of the spermatic cord at the internal abdominal ring.

Direct inguinal hernias are not generally congenital. Instead, they are acquired by the development of tissue deficiencies of the transversus abdominis muscle, which makes up the floor of the inguinal canal. Thus, these hernias protrude directly through a defect in the inguinal canal floor, rather than indirectly following the potential space of the processus vaginalis and the path of the spermatic cord.

The development of femoral herniation is not well understood. A femoral hernia can occur as a result of elevated intra-abdominal pressure. In this circumstance, preperitoneal fat can protrude through the femoral ring, with its accompanying pelvic peritoneum. The hernial sac can then migrate down along the femoral vessels into the anterior thigh. Women may be predisposed to femoral herniation due to weakness of the pelvic floor musculature from previous childbirth (Figure 4).

An understanding of the innervation of the inguinal region is important, because injury to the nerves in this area may cause significant problems. The major nerves in the inguinal region are the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerves. The ilioinguinal nerve traverses the inguinal canal near the external inguinal ring and provides unilateral sensory innervation to the pubic region and the upper portion of the scrotum or the labia majora. This is the nerve most commonly injured during open herniorrhaphy. The iliohypogastric nerve passes superior to the internal inguinal ring and provides sensory innervation to the skin superior to the pubis. The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve travels within the spermatic cord to provide sensation to the scrotum and the medial thigh. The femoral branch of this nerve supplies sensation to the skin of the anterior thigh2 (Figure 5).

Diagnosis

Most early inguinal hernias can be diagnosed by careful physical examination. Except for pain or a dull dragging sensation in the groin, the common reducible inguinal hernia usually does not cause significant symptoms.

Sonography may be useful in diagnosing inguinal hernias in patients who report symptoms but do not have a palpable defect. Ultrasound examination of the inguinal region with the patient in the supine and upright positions and with the Valsalva maneuver has been reported to have a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of greater than 90 percent.3 The ultrasound examination may also be helpful in differentiating an incarcerated hernia from a pathologic lymph node or other cause of a firm, palpable mass.

In the extremely rare patient with inguinal pain but no physical or sonographic evidence of inguinal herniation, computed tomographic scanning can be used to evaluate the pelvis for the presence of an obturator hernia.

Preoperatively, it is often difficult to differentiate the common indirect hernia from the less common direct defect. Even skilled examiners may be incorrect in up to 30 percent of cases. However, indirect and direct hernias need to be differentiated during surgery, because the approach to repair depends on the defect type. A hernia that is not repaired appropriately is more likely to recur.

Diagnosing inguinal hernias in children can be very difficult. Surgical consultation is usually warranted if the parent or other caregiver reports that the child has had a groin bulge.

The diagnosis of recurrent herniation is generally straightforward. However, it may be difficult to identify this problem in patients with scarring from a previous repair. In patients who have symptoms suggestive of recurrent herniation but no clinical findings, the diagnosis can usually be obtained through sequential serial examinations and the judicious use of imaging modalities.

Classification of Groin Hernias

Classification systems for groin hernias range from simple schemes to more complex systems with up to 20 categories. Most classification systems take into account the location of the defect (direct, indirect or femoral), the size of the defect and whether or not the herniation is recurrent.1

While it is often difficult to differentiate hernial types preoperatively, a consistent approach to classifying hernias during surgery can provide information that will allow institutions to compare the outcomes achieved with different types of hernia repair. If one system is universally used to classify hernias, surgeons will be able to perform individualized procedures for specific anatomic defects based on sound outcome data. While a broad consensus on the best classification system has not been achieved, the Nyhus classification system (Table 1)4 is often referred to in the literature.

Indications for Operative Intervention

Almost all groin hernias should be surgically repaired. When the potential complications of incarceration and strangulation are weighed against the minimal risks of hernia repair (particularly when local anesthesia is used), the early repair of groin hernias is clearly justified. This is especially true in the case of femoral hernias, since the rigid borders of the femoral canal increase the risk of incarceration.

Surgical repair of a hernia is not warranted in terminally ill patients with no evidence of incarceration. Patients with ascites generally should not undergo elective herniorrhaphy until their ascites is controlled.

While some surgeons believe that broad-based direct hernias do not need to be repaired, the uncertainty of determining the status of a hernia preoperatively argues against this practice. The presence of incarceration or strangulation usually mandates urgent operative repair.

Surgical Techniques

Based on operative intent and approach, the many different herniorrhaphy techniques can be grouped into four main categories.

GROUP 1: OPEN ANTERIOR REPAIR

Group 1 hernia repairs (Bassini, McVay and Shouldice techniques) involve opening the external oblique aponeurosis and freeing the spermatic cord. The transversalis fascia is then opened, facilitating inspection of the inguinal canal, the indirect space and the direct space. The hernia sac is usually ligated, and the canal floor is subsequently reconstructed (Figure 6).

The techniques in the open anterior repair group differ somewhat in their approach to reconstruction, but they all use permanent sutures to approximate the surrounding fascia and repair the floor of the inguinal canal. When performed by skilled surgeons, these repairs provide reliable, satisfactory results and have similar recurrence rates. With very large defects or with fascia of marginal quality, the tension of the sutures can lead to recurrence.

The techniques in group 1 are all well suited to the use of local anesthesia.

GROUP 2: OPEN POSTERIOR REPAIR

Posterior repair (iliopubic tract repair and Nyhus technique) is performed by dividing the layers of the abdominal wall superior to the internal ring and entering the properitoneal space. Dissection then continues behind and deep to the entire inguinal region.

Like the anterior approach, the posterior approach provides excellent visualization of the areas of concern in herniorrhaphy. The major difference between this technique and the anterior approach is that reconstruction is performed from the “inside.”

Excellent results have been reported for the posterior techniques, but problems related to suture tension remain.

Posterior repair is often used for hernias with multiple recurrences, because the approach avoids scar tissue from previous surgeries. It is probably best performed with the patient receiving regional or general anesthesia.

GROUP 3: TENSION-FREE REPAIR WITH MESH

The group 3 hernia repairs (Lichtenstein and Rutkow techniques) use the same initial approach as open anterior repair. However, instead of suturing the fascial layers together to repair the hernia defect, the surgeon uses a prosthetic, nonabsorbable mesh. This mesh allows the hernia to be repaired without tension being placed on the surrounding fascia (Figure 7). Excellent results have been achieved with this approach, and reported recurrence rates have been less than 1 percent.5

Some concern exists about the long-term safety of implanted prosthetic material, particularly the potential for infection or erosion. However, extensive accumulated experience with the hernia mesh has begun to alleviate many of these concerns, and tension-free repair continues to gain popularity.6

Tension-free repair can be performed using any type of anesthesia. This approach is well suited for outpatient herniorrhaphy performed with the patient receiving local anesthesia.

GROUP 4: LAPAROSCOPIC PROCEDURES

Laparoscopic hernia repair has become increasingly popular in the past few years, but the technique has also sparked significant controversy. Early in the development of the technique, hernias were repaired by placing a large piece of mesh over the entire inguinal region on top of the peritoneum. This approach was abandoned because of the potential for small-bowel obstruction and fistulae development caused by the exposure of bowel to mesh.

Today, most laparoscopic herniorrhaphies are performed using either the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach or the total extraperitoneal (TEP) approach. The TAPP approach involves placing laparoscopic trocars in the abdominal cavity and approaching the inguinal region from the inside. This allows the mesh to be placed and then covered with peritoneum. While the TAPP approach is a straightforward laparoscopic procedure, it requires entrance into the peritoneal cavity for dissection. Consequently, the bowel or vascular structures may be injured during the procedure (Figure 8).

In the TEP approach, an inflatable balloon is placed in the extraperitoneal space of the inguinal region. Inflation of the balloon creates a working space. For most surgeons, the TEP approach to hernia repair is more technically demanding than the TAPP approach.

In both the TAPP and TEP approaches, the hernia sac is reduced, and a large piece of mesh is placed to cover the indirect, direct and femoral areas of the inguinal region. The mesh is held in place by metal staples.

The advantage of these two procedures is that the small laparoscopic incision causes less pain and disability, promoting a faster return to work. This advantage appears to be most notable in patients who do heavy manual labor.7 Another advantage of the TAPP and TEP approaches is that bilateral hernias may be repaired simultaneously with no apparent increase in morbidity. Finally, these approaches can be particularly effective in patients with hernia recurrence after traditional open herniorrhaphy. In such patients, additional open anterior repairs have a higher failure rate and an increased rate of complications. The laparoscopic approach, similar to the open posterior approach, allows hernia repair to be performed in a previously untouched space.

Early results for laparoscopic surgery are promising, but information on long-term outcomes is currently unavailable. At present, the major drawbacks to laparoscopic herniorrhaphy are the cost of the laparoscopic equipment, the need for general anesthesia and the absence of long-term follow-up data.

Anesthesia

Hernia repair may be performed using general, regional (spinal/epidural) or local anesthesia. Several studies8,9 have found that, with proper preoperative preparation, more than 90 percent of groin hernias can be repaired with patients receiving only a local anesthetic. The advantages of local anesthesia include the very short recovery time and the ability to test the repair intraoperatively with a Valsalva maneuver. Use of local anesthesia also avoids the respiratory and immune depressive effects of general anesthesia. This advantage is particularly important in elderly and frail patients.

Local anesthesia alone does not allow for comfortable and technically optimal herniorrhaphy in patients with a very high anxiety level. Either general or regional (spinal) anesthesia may be used in these patients. General anesthesia provides the most comfort, but it has the highest risk. Patients occasionally respond poorly to a general anesthetic and require overnight hospitalization because of nausea, excessive sedation or urinary retention.

Spinal anesthesia provides excellent pain control during herniorrhaphy, and it carries slightly less risk than general anesthesia. The disadvantages of spinal anesthesia include the time required for the anesthetic to be placed and the possibility of incomplete sensory blockade. Urinary retention or a delay in the return of normal lower extremity sensation may mandate overnight observation following herniorrhaphy performed with regional anesthesia.

Operative Results

| Author | Type of repair | Number of patients | Follow-up period | Complication rate (%) | Hernia recurrence rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rutledge10 | McVay | 906 | 9 years | NR | 2.0 |

| Welsh and Alexander11 | Shouldice | 214,919 | 1 month to 40 years | NR | 0.1 |

| Shouldice | 2,748 | 35 years | NR | 1.5 | |

| Amid, et al.5 | Lichtenstein | 3,250 | Average of 4 years (range: 1 to 8 years) | NR | 0.1 |

| Rutkow and Robbins12 | Rutkow | 2,060 | NR | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Nyhus13 | Posterior iliopubic tract repair | 1,200 | 37 years | 1 to 6 | |

| Felix, et al.14 | Transabdominal preperitoneal laparoscopic repair | 733 | Average of 24 months (range: 1 to 44 months) | 13.0 | 0.3 |

| Total extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair | 382 | Average of 9 months (range: 1 to 44 months) | 11.0 | 0.3 |

| Author | Type of repair | Number of patients | Follow-up period | Complication rate (%) | Hernia recurrence rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panos, et al.15 | McVay | 136 | Average of 3 years, with a range of 1 to 5 years | NR | 9 |

| Shouldice | 136 | Average of 3 years, with a range of 1 to 5 years | NR | 7 | |

| Paul, et al.16 | Bassini | 125 | 3.3 years | 28 | 10 |

| Shouldice | 119 | 3.4 years | 29 | 2 | |

| Tran, et al.17 | Bassini | 63 | 2 years | 18 | 14 |

| Shouldice | 65 | 2 years | 18 | 11 | |

| Ferzli, et al.18 | Total extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair | 100 | Average of 12 months (range: 6 to 20 months | 6 | 0 |

| Payne, et al.7 | Transabdominal preperitoneal laparoscopic repair | 52 | Average of 10 months (range: 7 to 18 months | 12 | 0 |

| Lichtenstein | 58 | Average of 10 months (range: 7 to 18 months | 18 | 0 |

Most laparoscopic hernia repairs are being performed by skilled laparoscopic surgeons in specialty centers. Early studies showing acceptable outcomes for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy may reflect the same bias other procedure-focused centers have shown for open herniorrhaphy. Studies conducted at nonspecialty centers probably provide a more accurate view of hernia repair techniques and results.

Complications

The complications following herniorrhaphy are generally minor and self-limited. Wound hematomas and superficial wound infections are the most common problems, and they usually respond to conservative measures. More serious complications, such as major hemorrhage, osteitis and testicular atrophy, occur in fewer than 1 percent of patients undergoing herniorrhaphy.19 The minor and major complications of open and laparoscopic herniorrhaphies are compared in Table 4.

| Open repair | Laparoscopic repair | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Major | ||

| Hemorrhage | Hemorrhage | ||

| Testicular atrophy | Bowel injury | ||

| Vas deferens transaction | Bladder injury | ||

| Bowel injury | Major vessel injury | ||

| Bladder injury | |||

| Minor | Minor | ||

| Scrotal ecchymosis | Urinary retention | ||

| Wound infection | Trocar site hernia | ||

| Urinary retention | Nerve injury | ||

| Recurrence | Wound infection | ||

| Hydrocele | Small-bowel obstruction | ||

| Nerve transaction | |||

| Nerve entrapment | |||

NERVE ENTRAPMENT

Nerve entrapment is perhaps the most significant complication of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Most nerve entrapment syndromes are self-limited, respond to nonsteroidal analgesics and resolve with time. However, chronic neuralgia can develop.19

Entrapment of the ilioinguinal nerve produces pain in the groin and scrotum; extension of the hip frequently exacerbates the pain. Injury to the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve can cause hypersensitivity of the groin, scrotum and upper thigh, and can be associated with ejaculatory dysfunction. Injection of a long-acting local anesthetic along the course of these nerves is often helpful for diagnosing entrapment.

Following a period of nonoperative care, some patients with nerve entrapment need to be referred for surgical exploration and excision of the involved nerve. However, this corrective approach provides relief in less than 60 percent of patients.

While laparoscopic herniorrhaphy tends to offer greater protection to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, injuries to the femoral or the lateral femoral cutaneous nerves have been reported. Patients with such injuries present with pain in the groin and thigh. While these syndromes are often self-limited, surgery has been necessary to remove the staples that caused the neuralgia. These procedures have not provided pain relief in all patients.

HERNIA RECURRENCE

Recurrence is the most common long-term complication of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Approximately 50 percent of hernia recurrences do not present until at least five years after the original herniorrhaphy. An additional 20 percent of recurrences may not present for 15 to 25 years.20

The reported recurrence rates for surgically treated hernias vary widely, depending on the length and diligence of the follow-up period. In most reports, the recurrence rate varies from 5 to 8 percent for indirect hernias and is slightly higher for direct hernias. In some series, the recurrence rate following repair of a recurrent hernia is as high as 30 percent, which is significantly greater than the recurrence rate after initial repairs. Hernia recurrence following inguinal herniorrhaphy is usually caused by the breakdown of a repair performed with tension along the fascial suture lines. This breakdown may occur because of incomplete dissection, poor tissue quality (longstanding large hernias) or the patient's too-rapid return to daily activities. Systemic comorbidity, such as obesity, steroid use and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, influence wound healing and can affect the recurrence rate.21–23

Choice of Surgical Procedure

Inguinal hernias continue to be a source of morbidity and significant health care expenditure. No mechanism of preventive care is known, and surgical repair is almost always necessary. With the many techniques available, treatment can be individualized.

Most inguinal hernia repairs can be performed safely, accurately and cost-effectively using local anesthesia and an open anterior approach. Hernia recurrence rates of less than 4 percent have been reported for herniorrhaphies performed without prosthetic mesh by skilled surgeons.24 Open anterior repair performed with local anesthesia would appear to be the ideal approach in the young patient with an indirect hernia and no systemic disease.

Hernia repair using prosthetic mesh would be a good choice in the patient with a direct hernia or in the older patient with a longstanding hernia and attenuated fascia. In one recent study,5 more than 60 percent of blue collar workers and 90 percent of desk workers returned to work within 10 days after undergoing tension-free hernia repair with mesh. Recurrence rates in these cases have been reported to be 3 percent or less.7

Recurrent hernias repaired with classical herniorrhaphy not utilizing mesh have a reported recurrence rate of approximately 23 percent at three years.21 For this reason, recurrent hernias are best managed with open anterior or posterior mesh repair or, possibly, with a laparoscopic procedure. Bilateral hernias may also be addressed simultaneously, using either an open or a laparoscopic procedure. The approach is best determined by local expertise.

Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy is becoming a more common procedure. Several studies have demonstrated that this approach is safe and involves only minimal use of pain medication. The recurrence rate following this relatively new technique cannot as be completely assessed, but it has been reported to be less than 4 percent.25,26

The advantages of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy for an initial repair appear to be related to speedy convalescence and an earlier return to work. However, caution is advised, since a recent study27 of open herniorrhaphy showed that return to work was most often determined by the patient's type of insurance coverage rather than the type of procedure used to repair the hernia. Whether this will also be true for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy remains to be seen.

Compared with other types of hernia repair, laparoscopic herniorrhaphy is significantly more expensive. In some series, the laparoscopic approach has been 40 percent more costly than other approaches. Most current techniques for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy also subject patients to the risks and cost of general anesthesia. Performance of the laparoscopic TAPP repair also exposes patients to potential intra-abdominal injury and late adhesion formation. In contrast, tension-free repair using mesh, as well as other types of hernia repair, may be comfortably and safely completed with patients receiving only local anesthesia.

Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy may be best reserved for treatment of recurrent or bilateral hernias. However, individual preference cannot be ignored, and this technique may be advisable for initial hernia repair in selected patients.

In the managed-care environment, elective herniorrhaphy is under increasing pressure. Some state health plans do not reimburse for elective hernia repairs. The long-term impact of complications secondary to untreated herniation is not fully known. A decrease in surgical repair may lead to an increase in hospitalizations related to incarceration or strangulation.