Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(4):910-916

See related patient information handout on esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, written by the author of this article.

Esophageal atresia, with or without tracheoesophageal fistula, is a fairly common congenital disorder that family physicians should consider in the differential diagnosis of a neonate who develops feeding difficulties and respiratory distress in the first few days of life. Esophageal atresia is often associated with other congenital anomalies, most commonly cardiac abnormalities such as ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus or tetralogy of Fallot. Prompt recognition, appropriate clinical management to prevent aspiration, and swift referral to an appropriate tertiary care center have resulted in a significant improvement in the rates of morbidity and mortality in these infants over the past 50 years.

Esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula occurs in one of 3,000 to 5,000 births. Family physicians who care for neonates should be aware of both the clinical presentation and management of neonates with this condition. Before the performance of the first successful repair in 1939, this condition was fatal. Over the past 50 years, refinements in neonatal surgical technique, preoperative support, anesthesia and neonatal intensive care have improved the outcome. It is also recognized that prompt diagnosis with appropriate clinical management and expeditious referral to a tertiary care center have had a dramatic impact on the improved survival of these infants. Estimates today suggest that, in the absence of other severe anomalies, survival rates in these infants approach 100 percent.1–4

Illustrative Case

A female neonate weighing 3,315 g (7 lb, 5 oz) was delivered after a gestation of 41 weeks and five days by uncomplicated primary low-transverse cesarean section. This was the first pregnancy for the 26-year-old mother. Cesarean section was performed secondary to arrest of dilatation at 7 cm. The maternal history was remarkable for a positive result on Chlamydia screening at 10 weeks of gestation and mild anemia that was treated with iron, ascorbic acid and prenatal vitamins. The infection was treated with azithromycin, and the patient subsequently had a negative test for Chlamydia. All other prenatal screening laboratory tests were unremarkable. Total weight gain for the pregnancy was 23.6 kg (52 lb). Fundal height consistently agreed with dates throughout the pregnancy.

A routine post-date non-stress test one week before delivery was reactive. An abdominal ultrasonogram obtained at the same time revealed an amniotic fluid index of 21.5. At delivery, the infant was vigorous and had Apgar scores of 9 at one minute and 9 at five minutes. The initial physical examination at one hour of life was remarkable only for a slight increase in white oral secretions, which cleared with suctioning. The patient passed a meconium stool in the first six hours of life and reportedly tolerated her first feeding without difficulty.

At approximately 10 hours of life, the infant was noted to have some crackles on routine auscultation. Respiratory rate was normal. The infant's oral secretions were also increased. Esophageal atresia was suspected, and an attempt was made to pass a nasogastric tube. A chest radiograph was obtained (Figure 1). Nasogastric aspiration revealed a copious, mucus-like, white aspirate. A diagnosis of esophageal atresia with probable tracheoesophageal fistula was made, and the infant was transferred to a tertiary care facility with pediatric surgery capabilities. The patient underwent surgery on the second day of life. Bronchoscopy confirmed the tracheoesophageal fistula (Figure 2), and primary surgical repair was accomplished.

Embryology

The esophagus and trachea derive from the primitive foregut. During the fourth and fifth weeks of embryologic development, the trachea forms as a ventral diverticulum from the primitive pharynx (caudal part of the foregut),5 as illustrated in Figure 3. A tracheoesophageal septum develops at the site where the longitudinal tracheoesophageal folds fuse together. This septum divides the foregut into a ventral portion, the laryngotracheal tube and a dorsal portion (the esophagus). Esophageal atresia results if the tracheoesophageal septum is deviated posteriorly. This deviation causes incomplete separation of the esophagus from the laryngotracheal tube and results in a concurrent tracheoesophageal fistula.

Esophageal atresia as an isolated congenital anomaly may occur, rarely. In these cases, the atresia is attributable to failure of the recanalization of the esophagus during the eighth week of development and is not associated with tracheoesophageal fistula. A recent experimental animal model, wherein prenatal exposure to adriamycin leads to esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, may increase our understanding of the embryogenesis of these malformations.6

Pathology

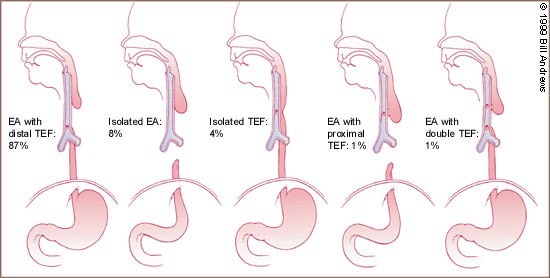

Esophageal atresia is characterized by incomplete formation of the esophagus. It is often associated with a fistula between the trachea and the esophagus. Many anatomic variations of esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula have been described7,8 (Figure 4). Table 11,3,9–12 provides a summary of the incidence of these variations at multiple worldwide surgical centers. The most common variant of this anomaly consists of a blind esophageal pouch with a fistula between the trachea and the distal esophagus, which is estimated to occur 84 percent of the time. The fistula often enters the trachea close to the carina.

| Study (dates) | Number of study subjects | Type A number | Type B number | Type C number | Type D number | Type E number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German, et al.9 (1964–1974) | 102 | 6 | 2 | 83 | 9 | 2 |

| Sillen, et al.10 (1967–1984) | 110 | 7 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 1 |

| Holder, et al.11 (1973–1986) | 100 | 2 | 1 | 85 | 6 | 6 |

| Poenaru, et al.12 (1969–1989) | 95 | 8 | 0 | 80 | 1 | 6 |

| Engum, et al.3 (1971–1993) | 227 | 29 | 2 | 178 | 5 | 13 |

| Spitz, et al.1 (1988–1994) | 410 | 27 | 4 | 353 | 9 | 17 |

| Total | 1,044 | 79 (8%) | 10 (1%) | 879 (84%) | 31 (3%) | 45 (4%) |

The proximal esophageal pouch is often hypertrophied and dilated secondary to the fetus' efforts to swallow amniotic fluid. The muscular pouch may also compress the trachea, and this compression has been implicated in the development of the tracheomalacia that is sometimes reported in these infants.

The second most common anomaly is pure atresia without tracheoesophageal fistula. This condition is usually associated with an underdeveloped distal esophageal remnant, making surgical repair more cumbersome. The third most common variation is the H-type fistula, which consists of a tracheoesophageal fistula without esophageal atresia. This aberration is more difficult to diagnose clinically. If the fistula is long and oblique, the symptoms may be minimal, and the condition may not be identified for many years.

Associated Defects

Associated congenital anomalies (Table 2) are discovered in approximately one half of infants with esophageal atresia.13–15 Other midline defects are the most common of these anomalies. Most infants have more than one malformation. Cardiac anomalies are encountered in approximately one quarter of these infants and account for approximately one third of all anomalies identified. Ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus and tetralogy of Fallot are the most frequently reported cardiac defects. The more complex cardiac malformations are often associated with multiple other anatomic defects and have been associated with a poorer outcome. Gastrointestinal anomalies, including imperforate anus, duodenal atresia and malrotation, make up one fourth of the identified defects and occur in approximately 16 percent of infants with esophageal atresia.

| System affected | Potential anomalies |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | Hemivertebrae, radial dysplasia or amelia, polydactyly, syndactyly, rib malformations, scoliosis, lower limb defects |

| Gastrointestinal | Imperforate anus, duodenal atresia, malrotation, intestinal malformations, Meckel's diverticulum, annular pancreas |

| Cardiac | Ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, atrial septal defect, single umbilical artery, right-sided aortic arch |

| Genitourinary | Renal agenesis or dysplasia, horseshoe kidney, polycystic kidney, ureteral and urethral malformations, hypospadias |

Musculoskeletal defects are common and include vertebral body abnormalities and defects of the ribs and extremities. Urinary tract malformations such as ureteral abnormalities, hypospadias, horseshoe kidney and renal agenesis can also occur. Approximately 10 percent of patients with esophageal atresia have an abnormality of the urinary tract or the musculoskeletal system. The acronym VATER, or VACTERL (vertebral defect, anorectal malformation, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomaly, radial dysplasia and limb defects), has been used to describe the condition of multiple anomalies in these infants.16 Up to 10 percent of infants with esophageal atresia have the VATER syndrome. Isolated esophageal atresia is associated with a higher incidence of other malformations than esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula. The H-type tracheoesophageal fistula has been associated with other anomalies less often.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The first sign of esophageal atresia in the fetus may be polyhydramnios in the mother. Polyhydramnios, however, has a broad differential diagnosis, including intestinal atresia, fetal hydrops, neural tube defects, diaphragmatic hernia and intrathoracic lesions. The inability to identify the fetal stomach bubble on a prenatal ultrasonogram in a mother with polyhydramnios makes the diagnosis of esophageal atresia more likely.17–18 Prematurity has also been associated with esophageal atresia.

Clinically, the diagnosis of esophageal atresia sometimes requires a high degree of suspicion. Classically, the neonate with esophageal atresia presents with copious, fine, white, frothy bubbles of mucus in the mouth and, sometimes, the nose. These secretions may clear with aggressive suctioning but eventually return. The infant may have rattling respirations and episodes of coughing, choking and cyanosis. These episodes may be exaggerated during feeding. If a fistula between the esophagus and the trachea is present, abdominal distention develops as air builds up in the stomach. The abdomen will be scaphoid if no fistula exists. Other anomalies, such as imperforate anus, skeletal abnormalities or cardiac conditions, may be evident on physical examination, but the physical examination may be otherwise unremarkable.

If esophageal atresia is suspected, a radiopaque 8 French (in preterm infants) or 10 French (in term infants) nasogastric or feeding tube should be passed through the nose to the stomach. In patients with atresia, the tube typically stops at 10 to 12 cm. The normal distance to an infant's gastric cardia is approximately 17 cm. If a soft, flexible tube is used, it may curl in the upper pouch and give the physician a false sense that it has passed to the stomach. In cases of suspected esophageal atresia, chest radiographs (posteroanterior and lateral views) should be obtained to confirm the position of the tube. The radiograph should include the entire abdomen. In patients with esophageal atresia, air in the stomach confirms the presence of a distal fistula, and the presence of bowel gas rules out duodenal atresia. The chest radiograph provides information about the cardiac silhouette, the location of the aortic arch and the presence of vertebral and rib anomalies, as well as the presence of pulmonary infiltrates. Contrast studies are seldom necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Such studies increase the risk of aspiration pneumonitis and reactive pulmonary edema, and usually add little to plain film radiographs.

Management and Treatment

Once a diagnosis of esophageal atresia is established, preparations should be made for surgical correction. Measures should be taken to reduce the risk of aspiration. The oral pharynx should be cleared, and an 8 French sump tube placed to allow for continuous suctioning of the upper pouch. The infant's head should be elevated. Intravenous fluids (10 percent dextrose in water) should be started. Oxygen therapy is used as needed to maintain normal oxygen saturation. In infants with respiratory failure, endotracheal intubation should be performed. Bag-mask ventilation is not appropriate since it may cause acute gastric distention requiring emergency gastrostomy.

If sepsis or pulmonary infection is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotics (such as ampicillin plus gentamicin) should be administered. Some sources, however, recommend starting intravenous antibiotics empirically because of the increased risk of aspiration.4,7 The infant should also be transferred to a tertiary care center with a neonatal intensive care unit.

Before surgical correction, the infant must be evaluated thoroughly for other congenital anomalies. Chest radiographs should be evaluated carefully for skeletal abnormalities, cardiovascular malformations, pneumonia and a right aortic arch. An abdominal radiographic series will aid evaluation of skeletal abnormalities, intestinal obstruction and malrotation. The chest and abdominal radiographs are usually sufficient; a contrast upper gastrointestinal series is not usually necessary for evaluation of classic esophageal atresia. An echocardiogram and renal ultrasonogram may also be obtained.

Gastrostomy for gastric decompression is reserved for use in patients with significant pneumonia or atelectasis, to prevent reflux of gastric contents through the fistula and into the trachea. Healthy infants without pulmonary complications or other major anomalies usually can undergo primary repair in the first few days of life. Survival rates in this group of patients approach 100 percent.1–4,10–15

Surgical repair is delayed in infants with low birth weight, pneumonia or other major anomalies. Premature low-birth-weight infants and infants with major concomitant malformations are typically treated with parenteral nutrition, gastrostomy and upper pouch suction until they are appropriate surgical candidates. The survival rate in this group is lower but in the range of 80 to 95 percent. Cardiac anomalies typically are the cause of death in these more complicated cases.

Outcome

Most neonates who undergo repair of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula have some degree of esophageal dysmotility.2,3,7,19 The extent of the repair dictates the severity of subsequent complications. Strictures at the site of the anastomosis are common and may subsequently require dilatation. Serial esophagraphy should be performed at two months, six months and one year of age, or whenever swallowing difficulties occur. Recurrence of the tracheoesophageal fistula has been reported; recurrence requires repeat surgical correction.3,4,7,20,21 Recurrence is most common at the site of the primary anastomosis. Tissue damage of the poorly vascularized distal esophagus and surgical dissection performed too close to the trachea have been postulated as risk factors for fistula recurrence.20

Approximately one half of patients with surgically corrected esophageal atresia develop gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).3,7,21 Of those who develop GERD, approximately one half respond to routine medical therapy with prokinetic agents, histamine H2 receptor blockers, or both, and one half require surgical intervention for correction. Patients with longstanding GERD may develop esophageal mucosal changes such as esophagitis and gastric metaplasia (Barrett's esophagus).21 Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus resulting from gastric metaplasia was reported in a patient with esophageal atresia 20 years after neonatal anastomosis. Other cases of Barrett's esophagus in patients with esophageal atresia have been reported. For these reasons, some authors advocate long-term endoscopic follow-up in these patients.21