Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(11):2267-2274

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Cultural competency is an essential skill for family physicians because of increasing ethnic diversity among patient populations. Culture, the shared beliefs and attitudes of a group, shapes ideas of what constitutes illness and acceptable treatment. A cross-cultural interview should elicit the patient’s perception of the illness and any alternative therapies he or she is undergoing as well as facilitate a mutually acceptable treatment plan. Patients should understand instructions from their physicians and be able to repeat them in their own words. To protect the patient’s confidentiality, it is best to avoid using the patient’s family and friends as interpreters. Potential cultural conflicts between a physician and patient include differing attitudes towards time, personal space, eye contact, body language, and even what is important in life. Latino, Asian, and black healing traditions are rich and culturally meaningful but can affect management of chronic medical and psychiatric conditions. Efforts directed toward instituting more culturally relevant health care enrich the physician-patient relationship and improve patient rapport, adherence, and outcomes.

Cultural diversity is increasing worldwide as immigration, travel, and the global economy make national borders more permeable. Latinos of all nationalities will make up the largest U.S. minority group with 12.5 percent of the population, followed by blacks (12.3 percent) and Asians (3.6 percent).1 Ten percent of the U.S. population is foreign-born. By 2050, minorities will make up approximately 47 percent of the U.S. population.2

Cultural understanding between physicians and patients will improve adherence, patient care, and clinical outcomes. Table 1 lists Web sites for additional information regarding cross-cultural medicine.

American Translators Association

|

Cultural Competency

Culture is defined as the beliefs and attitudes that are learned and shared by members of a group.3 Cultural competency refers to possessing knowledge, awareness, and respect for other cultures. Physicians must respectfully elicit needed information from patients from various cultures to make accurate diagnoses and negotiate acceptable treatment goals.4 Ethnocentrism, the conviction that one’s own culture is superior, can hinder effective cross-cultural care.

It is important to distinguish between stereotyping (the mistaken assumption that everyone in a given culture is alike) and generalizations (awareness of cultural norms). Generalizations can serve as a starting point and do not preclude factoring in individual characteristics such as education, nationality, faith, and acculturation. Every patient is unique.

Views of Disease Causation

A person’s worldview (i.e., basic assumptions about reality) is closely linked with his or her cultural and religious background and has profound health care implications. For example, persons with chronic diseases who believe in fatalism (i.e., predetermined fate) often do not adhere to treatment, because they believe that medical intervention cannot affect their outcomes. Patients’ worldviews and religious beliefs also affect how they view disease causation. Some see illness as having not only physical but also spiritual causes. Physicians should respectfully explore a patient’s beliefs within the context of the patient’s religion and culture. Some immigrants transitioning between belief systems may hold several viewpoints simultaneously.

Asian and Latino cultures believe that a “hot-cold” balance is necessary for health. In both cultures, hot conditions should be managed with cold therapies and vice versa, and any hot-cold imbalance is thought to foster disease. For example, a mother might stop giving her child vitamins (a hot treatment) if the child gets a rash (a hot condition).5 Some Asian patients believe that germs play a role in disease, but that hot-cold imbalances make a person susceptible to illness.3

A worldview is internally consistent and serves as a source of comfort to most patients. Many patients use home remedies or visit traditional healers before seeking conventional medical treatment.6 Others return to traditional healers in lieu of completing an ongoing conventional medical work-up. Patients may lose confidence in their physicians if they do not receive prompt, culturally comprehensible diagnoses.7 Clinical success often depends on communicating with these healers and prioritizing tests and treatments.

Cross-Cultural Interview

The cross-cultural interview requires time and patience. First, “small talk” can establish trust (confianza in Spanish) between the patient and physician. Physicians should use a patient’s formal name if they are unsure of the appropriate way to address the patient. Patients sometimes will avoid eye contact with physicians out of respect, especially if they are of a different gender or social status. Orthodox Jews and persons from some Islamic sects do not allow opposite-sex touching (even hand shaking). In these groups it is best for patients to have a same-sex physician. In other low-touch societies (e.g., Asians), it is merely necessary for physicians to explain what they will be doing during the examination.

Language barriers can create misunderstandings. Physicians should use body language and speak slowly and directly to the patient (rather than the interpreter) using short sentences and a normal tone of voice. Idioms, a loud tone of voice, and confusing phraseology should be avoided. Patients may say they understand something or nod in agreement even if they do not comprehend. Embarrassment or respect may prevent them from asking necessary questions. Head wagging by South Asians should not be confused with head shaking or disagreement: it simply means, “I hear what you are saying.” East Asians may smile from embarrassment rather than amusement and often find it culturally difficult to refuse a request directly.

An interpreter is necessary if the physician and patient do not speak the same language fluently. An interpreter also may assist in explaining cultural differences. Although family members or friends are often the most convenient interpreters, this practice may breach confidentiality and may make it impossible to assess sensitive issues such as sexuality and domestic violence. Whenever possible, a trained medical interpreter or a bilingual staff member should act as the interpreter.8

During the interview, the physician should ask the patient what the illness means to him or her and what treatments the patient is currently undergoing. This will allow the physician to explain the different treatment options and find a mutually acceptable treatment plan. The physician should provide instructions, preferably in writing (if the patient or a family member is literate), and ask the patient if the plan is acceptable. Rather than asking, “Do you understand?” the physician should have patients repeat the instructions in their own words.9 Table 210 includes common cross-cultural interview questions.

| What do you call the illness? |

| What do you think has caused the illness? |

| Why do you think the illness started when it did? |

| What problems do you think the illness causes? How does it work? |

| How severe is the illness? Will it have a long or short course? |

| What kind of treatment do you think is necessary? What are the most important results you hope to receive from this treatment? |

| What are the main problems the illness has caused you? |

| What do you fear most about the illness? |

Cultural Differences

Time perception and management differ among cultures. For example, some persons in many cultures (e.g., Latino, black) may have a relaxed sense of time, and personal relationships are considered more important than schedules. If a patient is late, tactfully explain the importance of punctuality in the U.S. medical setting.

Perceptions of personal space also vary among cultures. For example, some Latinos perceive Anglos as distant because they prefer more personal space during a conversation.

Gestures are another source of misunderstanding among cultures. For example, in much of Latin America, the North American “OK” sign (i.e., pinched thumb and forefinger) may be considered obscene. Often, beckoning is performed with the hand held palm down and all fingers waved; using the index finger to beckon or point may be considered rude or insulting. For many Asians, exposing the sole of the foot or pointing with the foot is an anathema, as is touching the head. In many non-Western cultures, the left hand is used for personal hygiene and is considered unclean. Therefore, prescriptions and samples should not be offered with this hand.11

In some cultures, a negative prognosis traditionally is conveyed first to the family and later to the patient. They believe that informing the patient of a bad prognosis results in hopelessness and then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy (i.e., the patient will give up and the bad prognosis will come true).12 Physicians should explain to these patients and their families that informing patients first is the standard practice in the United States, and then ask patients which approach they would prefer.

LATINO CULTURE

Latinos are believed to be the largest U.S. minority group. Mexicans are predominant in the United States (66 percent of Latinos), but many other nationalities and subcultures also are represented. Experts predict that Latinos will make up 24.5 percent of the U.S. population by 2050.1,13 Poverty, immigration status, and mistrust of the medical establishment may keep many Latinos from seeking health care. Although the rate of diabetes is up to five times higher in Mexican Americans than in non-Latino whites,14 their coronary heart disease mortality rate is significantly lower than would be expected—an unexplained anomaly termed the “Latino paradox.”6

Latino healing traditions include Curanderismo in Mexico and much of Latin America, Santeria in Brazil and Cuba, and Espiritismo in Puerto Rico. Most of these traditions distinguish natural illness from supernatural illness. Curanderos (traditional healers) use incantations and herbs, sobadores practice manipulation, parteras are midwives, and abuelas (literally “grandmothers,” but they are not necessarily related to the patient) provide initial care. Many traditional Latin American diagnoses remain popular among U.S. immigrants, but some traditional treatments, such as azarcan and greta (lead salts) and azogue (mercury), are harmful.15

Traditional Latino diagnoses (Table 313) are often alternative cultural interpretations of common symptoms and may be categorized as hot and cold illnesses (Table 414). For example, essential hypertension may be considered a hot condition that should be managed with cold therapies such as passionflower tea. It is critical to address the patient’s understanding of such chronic diseases at the start of therapy.

| Diagnosis | Characteristics | Traditional treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Ataque de nervios (“nervous attack”) | Intense but brief release of emotion believed to be caused by family conflict or anger (e.g., screaming, kicking) | No immediate treatment other than calming the patient |

| Bilis (“bile,” rage) | Outburst of anger | Herbs, including wormwood |

| Caida de la mollera (“fallen fontanel”) | Childhood condition characterized by irritability and diarrhea believed to be caused by abrupt withdrawal from the mother’s breast | Holding the child upside down or pushing up on the hard palate |

| Empacho (indigestion or blockage) | Constipation, cramps, or vomiting believed to be caused by overeating | Abdominal massage and herbal purgative tea, |

| Fatiga (shortness of breath or fatigue) | Asthma symptoms (especially in Puerto Rican usage) and fatigue | Herbal treatments, including eucalyptus and mullein (gordolobo), steam inhalation |

| Frio de la matriz (“frozen womb”) | Pelvic congestion and decreased libido believed to be caused by insufficient rest after childbirth | Damiana tea (Turnera); rest |

| Mal aire (“bad air”) | Cold air that is believed to cause respiratory infections and earaches | Steam baths, hot compresses, stimulating herbal teas |

| Mal de ojo (“evil eye”) | A hex cast on children, sometimes unconsciously, that is believed to be caused by the admiring gaze of someone more powerful | The hex can be broken if the person responsible for the hex touches the child or if a healer passes an egg over the child’s body. |

| Children may wear charms for protection. | ||

| Mal puesto (sorcery) | Unnatural illness that is not easily explained | Magic |

| Pasmo (cold or frozen face; “lockjaw”) | Temporary paralysis of the face or limbs, often believed to be caused by a sudden hot-cold imbalance | Massage |

| Susto (fright-induced “soul loss”) | Post-traumatic illness (e.g., shock, insomnia, depression, anxiety) | Sweeping purification barrida ceremony that is repeated until the patient improves |

| Cold conditions |

| Cancer |

| Colic |

| Empacho (indigestion) |

| Frio de la matriz (“frozen womb”) |

| Headache |

| Menstrual cramps |

| Pneumonia |

| Upper respiratory infections |

| Hot conditions |

| Bilis (“bile,” rage) |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Gastroesophageal reflux or peptic ulcer |

| Hypertension |

| Mal de ojo (“evil eye”) |

| Pregnancy |

| Sore throat or infection |

| Susto (“soul loss”) |

ASIAN CULTURE

Asians are a culturally diverse group that includes Chinese (the largest subgroup), Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese nationalities. Common Asian cultural values include a hierarchical family structure, emphasis on accommodation rather than confrontation, and a strong sense of personal honor. In Asian culture, loss of self-respect or honor can be devastating, especially if it stems from public embarrassment or rebuke.

Traditional Chinese medicine remains popular. Chinese medicine is based on keeping the body’s yin (cold) and yang (hot) energies in harmonious balance through diet, lifestyle, acupuncture, and herbal regimens. Cold air and water are considered unhealthy;therefore, Chinese patients often reject ice water in favor of hot tea or hot water.

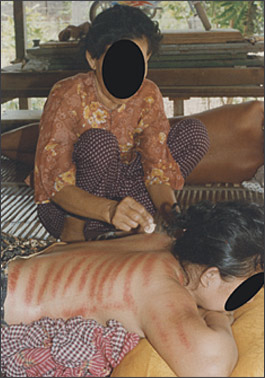

Some Asian therapies may cause bruises or scars, which may be mistaken for signs of abuse. For example, acupuncture is sometimes combined with moxibustion (i.e., smoldering herbs attached to an acupuncture needle or placed directly on the skin), which may cause scars resembling cigarette burns. Other Asian therapies, such as cupping (Figure 1) and coining (Figure 2), may leave bruises.16 Mongolian spots, common in Asian, Latino, and black infants, also resemble bruises and may be mistaken for signs of abuse.17

Many Asians are less likely to pursue psychiatric care and counseling because they consider psychiatric conditions shameful. Somatization, which commonly manifests as dizziness, palpitations, and stomach pain, is much more likely in such a cultural environment.2

Asian cultures, like Latino cultures, have their own culture-based interpretations of common illnesses. Table 518 lists common Asian diagnoses. A Japanese person obsessed with imagined body odor or bad breath has a variant of a social phobia termed taijin kyofusho. This fear of offending is a pathologic exaggeration of normal Asian cultural values, just as eating disorders are diagnosed primarily in Western cultures that value thinness.19

| Diagnosis (region) | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Amok (Malaysia, Southeast Asia) | Dissociative episode characterized by violent or homicidal behavior and usually preceded by brooding over real or imagined insults |

| Hwa-byung (Korea) | Epigastric pain, usually in a female patient, from an imagined abdominal mass |

| May be caused by unresolved anger | |

| Koro (Malaysia, Southeast Asia) | Fear that genitalia will retract into the body, causing death |

| Latah (Malaysia, Indonesia) | Easily frightened or startled |

| Often associated with trance-like behavior, echolalia, and hypersuggestibility | |

| Shen kui (China) | Anxiety, panic, and sexual complaints with no physical findings |

| Attributed to loss of semen or “vital essence” | |

| Patient believes condition is life-threatening. | |

| Dhat is a similar condition in India. | |

| Taijin kyofusho (Japan) | Pathologic fear of offending others by awkward behavior or an imagined physical problem such as body odor |

| Social phobia | |

| Wind illness (Asia) | Fear of wind or cold exposure with subsequent loss of yang energy |

| Often treated with coining in Asian folk medicine (Figure 2) |

BLACK CULTURE

Black Americans have maintained a distinctive culture even after living in the United States for many generations. Within this culture, however, vast differences exist regarding education and health care. Unfortunately, black Americans have a 5.9-year shorter life expectancy and a much higher incidence of hypertension and stroke compared with white Americans.20 Although poverty, discrimination, and limited access to health care explain some of these statistics, mistrust of “white” health care institutions can exacerbate the problem. Some of this mistrust may be justified. For example, in the Tuskegee syphilis study,21 black men with syphilis went untreated for decades so that researchers could observe the natural history of the disease.

Sodium-sensitive hypertension is common in blacks. Although “high blood” often is a slang term for high blood pressure, in many parts of the southern United States, it refers to thick or excessive blood in the circulation that “rises” in the body for periods of time and is best managed by treatments believed to reverse this condition. Another slang term, “highpertension,” commonly is perceived as a temporary rush of blood to the head. In one study,22 patients who had this alternative understanding of hypertension (i.e., that it is acute rather than chronic) were 3.3 times less likely to adhere to treatment as those who had a biomedical perception of their disease.

Traditional black terms include “falling out” (i.e., a stress-related collapse characterized by dizziness and temporary immobility while remaining fully conscious with functioning senses) and bad blood (i.e., blood contamination, which often refers to a sexually transmitted disease). Physicians also may encounter pica or earth-eating (i.e., eating nonedible items such as clay or laundry starch). Although also found in other cultures, pica is common among black women in the southern United States.20

Religious faith and prayer remain powerful influences within the black Christian community. Religious healing is often the first resort for devout black Christians, and church involvement is associated with improved health and social well-being.23 For black Muslims, the month-long Ramadan fast (held from sunrise to sunset) often requires modifying a medication schedule to once or twice daily dosing. Exceptions can be made for pregnant women, small children, and persons who are ill.24

Root medicine is an African healing tradition common in the southern United States in which healers or “root doctors” use incantations to lift hexes and heal the mind and body. Witchcraft and “fixing” (i.e., casting spells to cause illness) are widely accepted but seldom discussed openly. Conspiracy theories may be common in some black communities. For example, some blacks are reluctant to donate organs because they believe that they will receive less aggressive care.21

Emigration from Africa and the West Indies has increased in recent years. One controversy with African immigrants is how physicians should respond to female circumcision (also termed female genital mutilation), a traditional African procedure that may have severe health consequences. Female circumcision is illegal in the United States but is still practiced. This procedure is performed on preadolescent girls. It includes the milder sunna form, in which part of the clitoris is removed; and the much more extreme infibulation form, in which the labia are excised and most of the vaginal opening is sewn together.25 Another African tradition with potentially worrisome health consequences is “dry sex,” in which the vagina is packed with astringent herbs or powders. Subsequent damage to the vaginal mucosa may increase susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus.26