Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(6):676-682

A more recent article on plantar fasciitis is available.

Related letter: Acupuncture May Be Helpful for Patients with Plantar Fasciitis

Patient information: See related handout on plantar fasciitis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

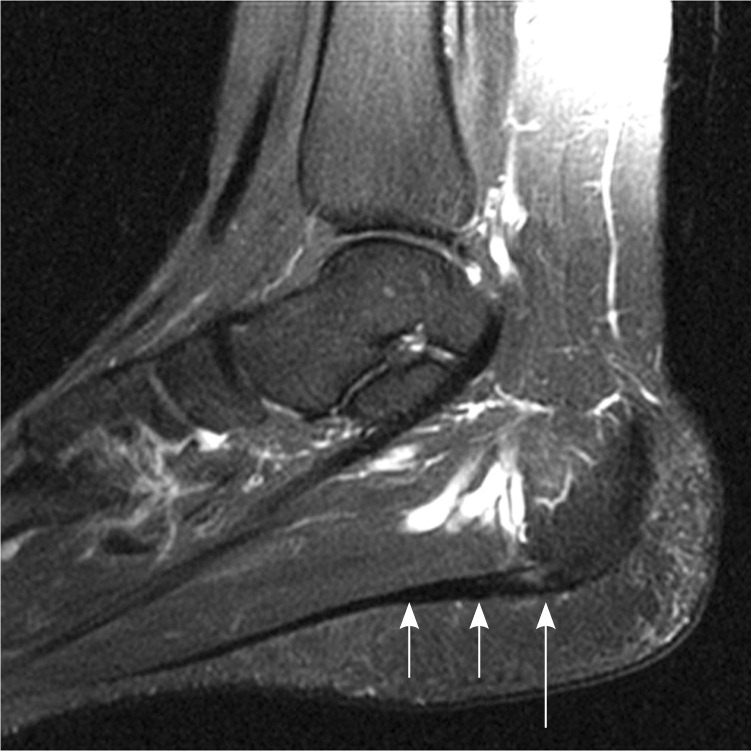

Plantar fasciitis, a self-limiting condition, is a common cause of heel pain in adults. It affects more than 1 million persons per year, and two-thirds of patients with plantar fasciitis will seek care from their family physician. Plantar fasciitis affects sedentary and athletic populations. Obesity, excessive foot pronation, excessive running, and prolonged standing are risk factors for developing plantar fasciitis. Diagnosis is primarily based on history and physical examination. Patients may present with heel pain with their first steps in the morning or after prolonged sitting, and sharp pain with palpation of the medial plantar calcaneal region. Discomfort in the proximal plantar fascia can be elicited by passive ankle/first toe dorsiflexion. Diagnostic imaging is rarely needed for the initial diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. Use of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging is reserved for recalcitrant cases or to rule out other heel pathology; findings of increased plantar fascia thickness and abnormal tissue signal the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. Conservative treatments help with the disabling pain. Initially, patient-directed treatments consisting of rest, activity modification, ice massage, oral analgesics, and stretching techniques can be tried for several weeks. If heel pain persists, then physician-prescribed treatments such as physical therapy modalities, foot orthotics, night splinting, and corticosteroid injections should be considered. Ninety percent of patients will improve with these conservative techniques. Patients with chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis lasting six months or longer can consider extracorporeal shock wave therapy or plantar fasciotomy.

Plantar fasciitis is a common cause of heel pain in adults. It is estimated that more than 1 million patients seek treatment annually for this condition, with two-thirds going to their family physician.1 Plantar fasciitis is thought to be caused by biomechanical overuse from prolonged standing or running, thus creating microtears at the calcaneal enthesis.1–3 Some experts have deemed this condition “plantar fasciosis,” implying that its etiology is a more chronic degenerative process versus acute inflammation.2,3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in diagnosing plantar fasciitis by showing increased plantar fascia thickness and abnormal tissue signal. | C | 3, 4 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can provide short-term improvement in pain from plantar fasciitis when used with other conservative therapies. | B | 5 |

| Prefabricated and custom-made foot orthotics are effective in reducing heel pain and improving foot function in patients with plantar fasciitis. | B | 9–11 |

| The use of anterior night splints can improve plantar fasciitis pain. | B | 9, 12 |

| Corticosteroid injections can provide relief for acute and chronic plantar fasciitis. | B | 14, 17 |

| Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is a viable treatment option for chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. | B | 21–24 |

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is based on patient history, risk factors (Table 11–3), and physical examination findings. Most patients have heel pain and tightness after standing up from bed in the morning or after they have been seated for a prolonged time. Typically, the heel pain will improve with ambulation but could intensify by day's end if the patient continues to walk or stand for a long time.

| Excessive foot pronation (pes planus) |

| Excessive running |

| High arch (pes cavus) |

| Leg length discrepancy |

| Obesity (body mass index greater than 30 kg per m2) |

| Prolonged standing/walking occupations (e.g., military personnel) |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

| Tightness of Achilles tendon and intrinsic foot muscles |

On physical examination, patients may walk with their affected foot in an equine position to avoid placing pressure on the painful heel. Palpation of the medial plantar calcaneal region will elicit a sharp, stabbing pain2,3 (Figure 1). Passive ankle/first toe dorsiflexion can cause discomfort in the proximal plantar fascia; it can also assess tightness of the Achilles tendon. Other causes of heel pain should be sought if history and physical examination findings are atypical for plantar fasciitis (Table 2).2

| Etiology | Associated characteristics | |

|---|---|---|

| Neurologic | ||

| Medial calcaneal and abductor digiti quinti nerve entrapment | Pain and burning sensation in the medial plantar region | |

| Neuropathies | Diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, vitamin deficiency | |

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome | Burning sensation in medial plantar region | |

| Skeletal | ||

| Acute calcaneal fracture | Direct trauma, unable to bear weight | |

| Calcaneal apophysitis (Sever disease) | Adolescent, posterior calcaneal pain | |

| Calcaneal stress fracture | Insidious onset of pain, repetitive loading | |

| Calcaneal tumor | Deep bone pain | |

| Systemic arthritides (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, Reiter syndrome, psoriatic arthritis) | Multiple joint pain, bilateral heel pain | |

| Soft tissue | ||

| Achilles tendinitis | Posterior calcaneal/tendon pain | |

| Heel contusion | Direct fall on heel with bone/fat pad pain | |

| Plantar fascia rupture | Sudden plantar heel pain and ecchymosis | |

| Posterior tibial tendinitis | Posterior medial ankle/foot pain | |

| Retrocalcaneal bursitis | Pain in the retrocalcaneal region | |

Imaging

Imaging can aid in the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. Although not routinely needed initially, imaging can be used to confirm recalcitrant plantar fasciitis or to rule out other heel pathology.

Conservative Treatments

Plantar fasciitis, a self-limiting condition, usually improves within one year regardless of treatment. Many patients will seek help from their physician because of disabling heel pain with activities of daily living. Although several remedies exist for plantar fasciitis, there is little convincing evidence to support these various treatments. Conservative treatments usually start with patient-directed therapies and advance to physician-prescribed modalities based on how a patient's symptoms respond over weeks to months (Figure 4).2 Within this time, 90 percent of patients will improve with conservative therapies.2,5 If a patient's symptoms persist six months or longer, further invasive procedures are sometimes required.

REST AND ANALGESIC TREATMENTS

Patient-directed treatments to relieve plantar fasciitis pain consist of rest, activity modification, ice massage, and acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A small randomized, placebo-controlled study of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat plantar fasciitis showed short-term improvement in pain relief and disability when accompanied by other conservative treatments.5 There are few studies to support the benefit of these individual treatments used alone.

STRETCHING AND PHYSICAL THERAPY MODALITIES

Multiple physical therapy modalities are used for the management of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Most therapies are used in combination; therefore, there is poor evidence on which modality is best. Progressive plantar fascia and intrinsic foot muscle stretching techniques have been shown to reduce plantar fasciitis pain.6 Patients can be educated on how to perform foot and ankle stretches during physician office visits (see a video on stretching exercises for plantar fasciitis).

Stretching Exercises for Plantar Fasciitis

Courtesy of Summa Health System, Akron, Ohio.

Eccentric stretches, defined as exercises performed under load while the muscle is slowly lengthened (Figure 5), have supportive evidence in improving various tendinopathies, but have yet to be adequately studied in plantar fasciitis.7 Additional prescribed physical therapy modalities, including deep myofascial massage and iontophoresis, can be performed by a physical therapist. Deep myofascial massage of the plantar fascia, manually or with instrumentation, is thought to promote healing by increasing the blood flow to the injured fascia. Most evidence for deep myofascial massage is anecdotal. Iontophoresis uses electrical pulses to cause absorption of topical medication into the soft tissue beneath the skin. In a study of 31 patients, iontophoresis with acetic acid or dexamethasone had some effectiveness in treating plantar fasciitis,8 but further study is needed to substantiate the results.

ARCH SUPPORTS, HEEL CUPS, AND NIGHT SPLINTS

Foot orthotics are commonly recommended for persons with plantar fasciitis to aid in preventing overpronation of the foot and to unload tensile forces on the plantar fascia. There are many different orthotics available, including viscoelastic heel cups (Figure 6), prefabricated longitudinal arch supports (Figure 7), and custom-made full-length shoe insoles (Figure 8). A recent meta-analysis and comparative trial examined the effectiveness of foot orthotics in patients with plantar fasciitis and found that prefabricated and custom foot orthotics can decrease rear foot pain and improve foot function.9,10 A Cochrane review found that custom foot orthotics may not reduce foot pain any more than prefabricated foot orthotics, but that when custom foot orthotics are used in conjunction with a night splint, patients may get heel pain relief.11

Night splints prevent plantar fascia contracture by keeping the foot and ankle in a neutral 90-degree position, preventing foot plantar flexion during sleep. Night splints used alone have been shown to improve plantar fasciitis pain,9,12 but poor compliance because of sleep disturbance and foot discomfort has limited their long-term use. Anterior night splints (Figure 9) seem to be better tolerated than posterior night splints12 (Figure 10).

Patients can purchase prefabricated night splints and arch supports from their local drug store. Physicians can have custom full-length arch support or anterior night splints made for patients by prescribing an orthotic evaluation and fitting from a local orthotist. Patients should obtain prior authorization from their insurance company before scheduling an orthotic evaluation.

INJECTIONS

Corticosteroid injections are commonly used in the treatment of acute and chronic plantar fasciitis and have proven effective. A prospective randomized study of 100 persons with plantar fasciitis compared a variety of treatments, including autologous blood injection, lidocaine (Xylocaine) needling, triamcinolone (Kenalog) injection, and triamcinolone needling, and found superior results in both triamcinolone groups.14 Possible risks associated with corticosteroid injection include fat pad atrophy and plantar fascia rupture.

In recent years, other injectable options have been used to treat plantar fasciitis. Even without the use of therapeutic medications, percutaneous fenestration (dry needling) has been shown to reduce pain in as early as four weeks.15 Hyperosmolar dextrose (prolotherapy), whole blood, platelet-rich plasma, and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) are being investigated as treatment options. In a pilot study, a 25% dextrose/lidocaine solution was shown to improve plantar fasciitis pain in 20 persons.16 Intralesional whole blood injections do not appear to be as effective as corticosteroid injections in treating plantar fasciitis.14,17 Platelet-rich plasma is produced via centrifuged autologous blood. The plasma collected is rich with platelets that release growth factors to stimulate healing in degenerative tissue. Currently, platelet-rich plasma has slight evidence to support its use for nonhealing tendinopathies.18 A randomized controlled trial is underway to determine if platelet-rich plasma is effective in treating plantar fasciitis.19 In a small pilot study, onabotulinumtoxinA injection was shown to relieve pain for as long as 14 weeks after injection.20

Chronic Recalcitrant Plantar Fasciitis Treatments

EXTRACORPOREAL SHOCK WAVE THERAPY AND PLANTAR FASCIOTOMY

If at least six months of conservative treatment is ineffective, a trial of extracorporeal shock wave therapy or plantar fasciotomy can be considered. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is used to promote neovascularization to aid in healing degenerative tissue found in plantar fasciitis.21 Over the past decade, multiple clinical trials on the use of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciitis have resulted in conflicting evidence. A 2005 meta-analysis showed an improvement in morning first-step heel pain in 897 patients with plantar fasciitis, but the clinical benefit was found to be insignificant on visual analog scales.22 A 2007 systematic review concluded that extracorporeal shock wave therapy is a viable treatment option for chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis, but each study used different treatment protocols.21 Benefits of extracorporeal shock wave therapy are that it is noninvasive and offers the hope for a faster recovery time. The adverse effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy are pain during and after the procedure, local swelling/ecchymosis, and numbness with dysesthesia.21

Plantar fasciotomy can be performed when all conservative measures have been ineffective. In two prospective studies comparing endoscopic plantar fasciotomy with extracorporeal shock wave therapy, approximately 80 to 85 percent of patients in both groups were satisfied with the results of treatment.23,24 Disadvantages of surgery include incision care, immobilization, and potential complications (e.g., arch flattening, nerve injury, calcaneal fracture, long recovery time).23,24