Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(3):299-306

Patient information: See related handout on chronic constipation in adults, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

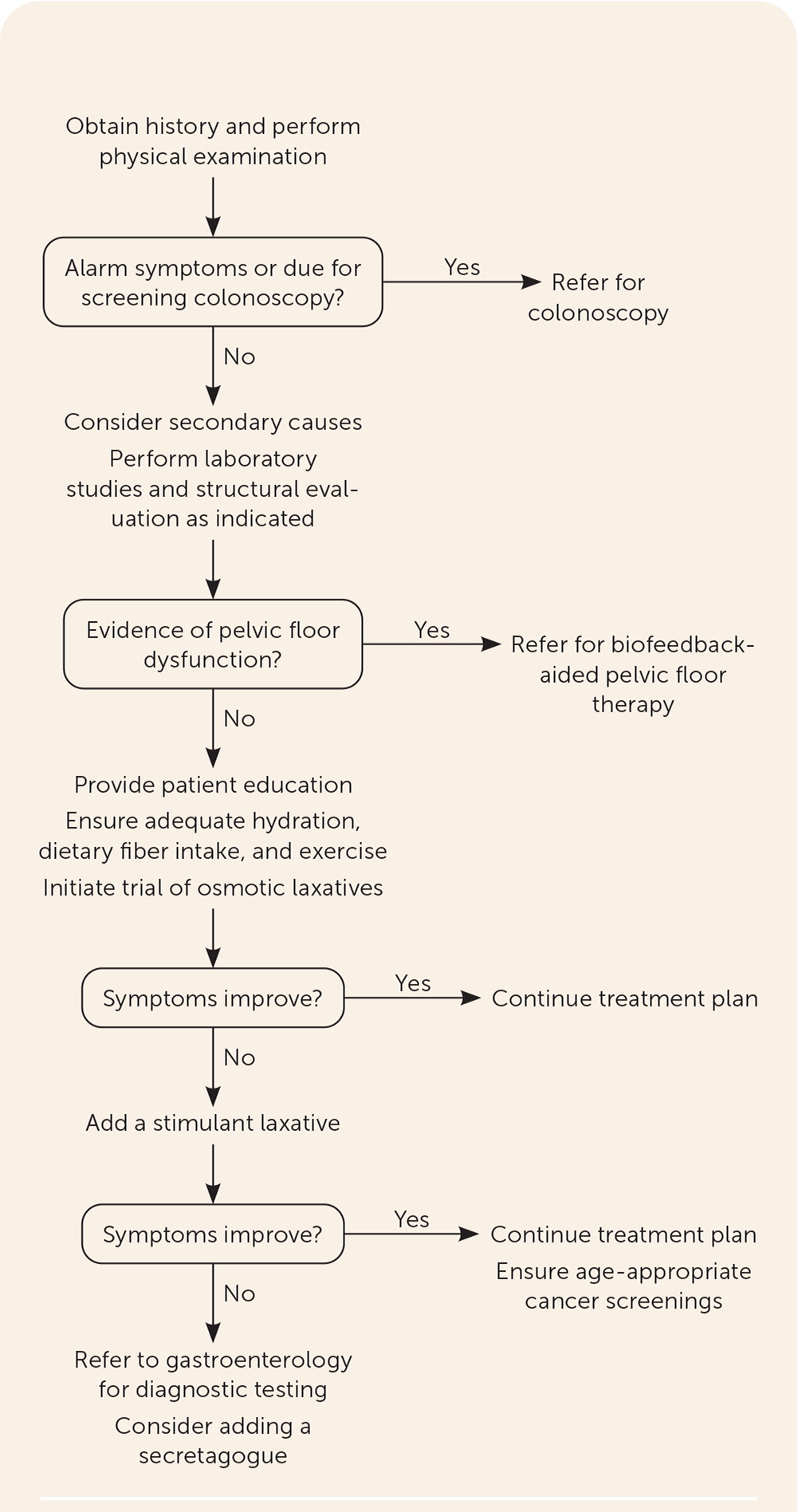

Chronic constipation has significant quality-of-life implications. Modifiable risk factors include insufficient physical activity, depression, decreased caloric intake, and aggravating medication use. Chronic constipation is classified as primary (normal transit, slow transit, defecatory disorders, or a combination) or secondary (due to medications, chronic diseases, or anatomic abnormalities). Evaluation begins with a detailed history, medication reconciliation, and physical examination. Routine use of laboratory studies or imaging, including colonoscopy, is not recommended in the absence of alarm symptoms. Patients with alarm symptoms or who are overdue for colorectal cancer screening should be referred for colonoscopy. First-line treatment for primary constipation includes ensuring adequate fluid intake, dietary fiber supplementation, and osmotic laxatives. Second-line therapy includes a brief trial of stimulant laxatives followed by intestinal secretagogues. If the initial treatment approach is ineffective, patients should be referred to gastroenterology for more specialized testing, such as anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Patients with refractory constipation may be considered for surgery. Those in whom pelvic floor dysfunction is identified early should be referred for pelvic floor therapy with biofeedback while first-line medications, such as bulk or osmotic laxatives, are initiated.

Constipation is a common condition in primary care that can significantly impact a patient's quality of life. In the United States, approximately 33 million adults have constipation, resulting in 2.5 million physician visits and 92,000 hospitalizations each year.1 Non-modifiable risk factors include female sex, lower socioeconomic status, comorbid illnesses, nursing home residence, and age older than 65 years.2,3 Modifiable risk factors include insufficient physical activity, depression, decreased caloric intake, and use of aggravating medications.4,5

Definitions

Constipation is defined as a stool frequency of fewer than three bowel movements per week. In addition to decreased frequency, patients often have a range of associated symptoms, including difficulty passing stools, hard stools, incomplete elimination, straining, or painful bowel movements.6 Chronic constipation occurs when symptoms are present for at least six months and can be divided into primary and secondary types.7,8

PRIMARY CONSTIPATION

The Rome IV criteria have been suggested as a tool to diagnose primary constipation (Table 1).7,8 Primary constipation can be classified as dysfunction of colonic motility (normal or slow transit) or the defecation process (pelvic floor dysfunction), although patients can have overlapping disorders.7–10 Diagnostic testing helps distinguish the different types of primary constipation but is not required before treatment.

|

Normal Transit Constipation. Patients with normal transit constipation (also referred to as functional constipation) report constipation symptoms and typically respond well to proper hydration, fiber, and osmotic laxatives.11,12 Diagnostic testing, which can determine normal transit times, is reserved for patients in whom initial treatment strategies have been ineffective and is not required before starting treatment.2,13 Patients may report many potential causes, including increased stress and changes in diet. Physicians should consider dietary intake when evaluating for this diagnosis, and simple changes to fiber and water intake are a cost-effective way to lower risk.

Slow Transit Constipation. Patients with slow transit constipation have slower than normal expected transit times during diagnostic testing. These transit times are specific to the type of test used, and not all tests are typically available in the primary care office. The Bristol Stool Form Scale (see Figure 1 in a previous American Family Physician article14) is a validated tool to assess stool consistency and a reliable indicator of colonic transit time, with types 1 and 2 correlating with slower colonic transit times.13

Defecatory Disorders. Defecatory disorders are characterized by disorganized contraction or relaxation of the pelvic floor, resulting in inadequate rectal propulsive forces or increased resistance to evacuation.2,6 High resting anal tone (anismus), incomplete relaxation or paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor, and mechanical obstruction may contribute to defecatory disorders.2,6 Fiber and laxatives are often not effective in treating this type of constipation, given the underlying pathophysiology. Diagnostic testing involves a balloon expulsion test performed in conjunction with anorectal manometry and is typically completed by gastroenterologists.8

SECONDARY CONSTIPATION

| Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

| Diet and lifestyle | Dehydration or inadequate fluid intake Immobility Low-fiber diet |

| Endocrine | Diabetes mellitus Hyperparathyroidism Hypothyroidism Pregnancy |

| Medications | Analgesics: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates Anticholinergic agents Antidiarrheals (overuse) Calcium channel blockers: nifedipine, verapamil Cation-containing agents: aluminum, calcium, iron Diuretics Tricyclic antidepressants |

| Metabolic | Chronic kidney disease Electrolyte abnormalities (hypercalcemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia) |

| Neurologic | Central: dementia, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, spinal cord injury, stroke, traumatic brain injury Peripheral: autonomic neuropathy, diabetes, Hirschsprung disease |

| Psychiatric or psychosocial | Abuse Anorexia nervosa Dementia Depression |

| Structural | Colonic stricture or obstruction: inflammation, ischemia, postradiation External compression Neoplasia (colon cancer or other masses) |

Evaluation

Evaluation of constipation begins with a detailed history and physical examination. History-taking should include the Rome IV criteria (Table 17,8) and identify changes in stool caliber and consistency; when the stools changed; associated symptoms (i.e., abdominal pain, rectal pain); alleviating therapies; a Bristol Stool Form Scale classification; need for digital evacuation; and straining. Physicians should ask about alarm symptoms, which include unintentional weight loss, fatigue, rectal bleeding, change in bowel habits, and narrowing of the stool, and whether the patient has a family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease.6,7,9,10,16 A systematic review found that when rectal bleeding accompanied weight loss or changes in bowel habits, there was an increase in the likelihood of colorectal cancer (positive likelihood ratio = 1.9 and 1.8, respectively), whereas when rectal bleeding accompanied constipation or diarrhea, there was a lower risk of colorectal cancer (positive likelihood ratio ≤ 1).17

A complete medication reconciliation may identify contributory agents that can be stopped to improve outcomes (Table 2).15 A two-week bowel habits diary may identify causative agents and help quantify the severity of the patient's constipation. Assessment tools such as the Constipation Assessment Scale,18 Constipation Scoring System (https://thepelvicfloorsociety.co.uk/images/uploads/Cleveland_Clinic_Constipation_Sc.pdf), and Patient Assessment of Constipation–Symptoms questionnaire (https://thepelvicfloorsociety.co.uk/images/uploads/PAC_SYM.pdf) are effective at evaluating the severity of a patient's constipation and establishing a baseline to compare interventions.10 Physicians should examine the anus and perineum and include a digital rectal examination. The presence of hemorrhoids or anal fissures is indicative of excessive straining. Digital rectal examinations, which assess anal and pelvic floor musculature in addition to identifying rectal masses or obstructions, are a reliable tool to identify defecatory disorders and patients who may benefit from further physiologic testing.19

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Laboratory testing should be conducted as indicated based on findings from the history and physical examination to rule out secondary causes, but routine use of blood tests or imaging is not indicated in the absence of alarm symptoms.6,7,10 When the first- and second-line therapies described later in this article and in Table 39,20 are ineffective, additional testing should include a balloon expulsion test and anorectal manometry, followed by colonic transit studies and barium or magnetic resonance defecography when indicated, all of which are commonly performed in a specialty clinic. Figure 1 is a suggested approach to evaluation and management of chronic constipation.6,11,21

| Agent | Typical dosing | Approximate cost* | Treatment notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulking agents | |||

| Methylcellulose powder | 2 g per day | $16 for one 479-g bottle | Insoluble fiber; start with low dose and increase gradually |

| Polycarbophil (Fibercon) | 1.25 g one to four times per day, maximum: 5 g per day | $7 for one 140-capsule bottle | Soluble fiber; start with low dose and increase gradually |

| Psyllium (Metamucil) | 2.5 g to 30 g per day in divided doses | $11 for one 300-capsule bottle | Soluble and insoluble fiber; start with low dose and increase gradually |

| Osmotic laxatives | |||

| Polyethylene glycol 3350 formula (Miralax) | 17 g per day | $13 for one 510-g bottle | Titratable; response may take up to 72 hours; use shortest effective treatment duration; concern for dependence with long-term use |

| Lactulose | 15 mL to 30 mL per day | $15 for one 473-mL bottle | Response may take up to 48 hours; cramps and abdominal distention common |

| Magnesium hydroxide | 30 mL to 60 mL | $5 for one 769-mL bottle | Not for daily use; takes effect within six hours; may cause electrolyte disturbances |

| Magnesium citrate | 195 mL to 300 mL | $3 for one 296-mL bottle (one dose) | |

| Magnesium sulfate (Epsom salt) | 10 g to 20 g | $6 for one 3.6-kg container | |

| Stimulant laxatives | |||

| Bisacodyl (Dulcolax) | 5 mg to 15 mg once per day | $28 for a one-month supply | Short-term use; avoid use within one hour of consuming antacids or milk |

| Senna | One to two 8.6-mg tablets twice per day, maximum: four 8.6-mg tablets twice per day | $5 for a 60-tablet bottle | May cause urine discoloration and melanosis coli |

| Stool softener | |||

| Docusate calcium | 240 mg once per day | $12 for a 100-tablet bottle | Generally well tolerated |

| Secretagogues | |||

| Linaclotide (Linzess) | 145 mcg once per day | $509 for a one-month supply | Dosing differs for chronic constipation vs. irritable bowel syndrome with constipation |

| Lubiprostone (Amitiza) | 24 mcg twice per day | $158 for a one-month supply | Rarely can cause hypotension or syncope |

| Plecanatide (Trulance) | 3 mg to 6 mg per day | $540 for a 30-tablet bottle | Can cause hypersensitivity reaction |

| Serotonin agonist | |||

| Prucalopride (Motegrity) | 1 mg to 2 mg per day | $508 for a 30-tablet bottle | Serious adverse effects include suicidal thoughts and depression |

Colonoscopy has a low diagnostic yield in patients with primary chronic constipation without alarm symptoms. One systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies showed no increased prevalence of colorectal cancer in patients with constipation alone.22 However, patients with alarm symptoms and those who are due for colorectal cancer screening should be referred for a colonoscopy.17.22 An obstruction or mass is rarely the cause of chronic constipation, and a careful history evaluating for alarm symptoms can identify patients most likely to benefit from diagnostic colonoscopy.2,7,9,10

Management

NONPHARMACOLOGIC

Management of chronic constipation begins with improving symptoms through patient education and lifestyle modifications. Patients should be counseled that daily bowel movements are not necessary for gastrointestinal health, and timed stooling (i.e., first thing in the morning or after meals when colonic motility increases) can improve stool frequency.23 Additionally, placing the feet on a short stool while seated on the toilet can help straighten the anorectal junction to facilitate bowel movements.21

Exercise, Fluid, and Probiotics. Although there is no consistent evidence that physical activity relieves constipation, small studies have shown an increased risk of constipation in those with sedentary lifestyles and a decreased risk in those who exercise two to six times per week.24.25 Increased fluid intake alone has not been shown to improve constipation unless the patient is dehydrated; however, one small study showed that increased water intake, when coupled with appropriate daily fiber intake, improves stool frequency.26,27 Both interventions, despite limited evidence, are reasonable recommendations supported by clinical practice guidelines.6,10 Although probiotics may improve colonic transit, limited data support their use in treating constipation.28

Dietary Fiber. Dietary fiber increases stool bulk and bowel frequency in patients with chronic constipation, and increased fiber intake has fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects than laxatives and enemas.10,29–31 The U.S. Department of Agriculture's recommended fiber intake is 25 g per day for women and 38 g per day for men; however, the department's national “What We Eat in America” survey data from 2009 to 2010 indicate that most adults consume only 16 g per day.32,33 Patients not meeting the daily recommendation should increase their intake of fiber-rich foods, such as bran, fruits, vegetables, and nuts, by approximately 5 g per week to avoid the bloating and flatulence that can occur with sudden large increases in fiber intake.9,34 Table 4 lists the fiber content of common foods.35

| Food | Fiber content (g) |

|---|---|

| Fruits | |

| Raspberries, 1 cup | 8.0 |

| Pear | 5.5 |

| Apple with skin | 4.8 |

| Vegetables | |

| Green peas, 1 cup, cooked | 8.8 |

| Lentils, 1/2 cup, cooked | 7.8 |

| Black beans, 1/2 cup, cooked | 7.5 |

| Broccoli, 1 cup, cooked | 5.2 |

| Carrots, 1 cup, cooked | 4.8 |

| Grains | |

| Shredded wheat, 1 cup | 6.2 |

| Whole wheat spaghetti, 1 cup, cooked | 6.0 |

| Bran flakes, 3/4 cup | 5.5 |

| Nuts and seeds | |

| Pumpkin seeds, 1 oz | 5.2 |

| Almonds, 1 oz | 3.5 |

| Sunflower seeds, 1 oz | 3.1 |

Physical Therapy. Patients with constipation due to defecatory dysfunction, or pelvic floor dysfunction, should be managed with biofeedback-aided pelvic floor therapy. Biofeedback training involves visual or auditory feedback of anorectal and pelvic floor contraction and relaxation, often with a rectal plug, to help patients learn how to coordinate abdominal and pelvic floor activity.6,10,36,37 Biofeedback therapy is consistently superior to laxatives, sham therapy, and placebo in randomized controlled trials for defecatory dysfunction.36,37

PHARMACOLOGIC

Bulk Laxatives. Bulk laxatives work best in patients with normal transit constipation and contain soluble or insoluble fiber that absorbs water to increase the bulk of the stool and promote bowel movements. Adequate water intake is needed for proper function, and poor water intake may increase bloating and increase the risk of obstruction. A 2011 systematic review of patients with chronic constipation compared soluble and insoluble fiber with placebo and found that soluble fiber improved global symptoms (86.5% vs. 47.4%), decreased straining (55.6% vs. 28.6%), decreased pain with defecation, improved stool consistency, and increased the mean number of stools per week (3.8 stools per week compared with a baseline of 2.9 stools per week). The evidence for insoluble fiber was inconsistent.38

Osmotic Laxatives. Osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol (Miralax), lactulose, and magnesium-based products increase water secretion into the intestinal lumen and are an appropriate first-line pharmacologic therapy, with polyethylene glycol considered to be better than other osmotic laxatives. In a 2010 Cochrane review, polyethylene glycol was superior to lactulose for improving stool frequency per week, form of stool, abdominal pain, and the need for additional medications.39 Although generally well tolerated, osmotic laxatives can cause electrolyte disturbances within the colon, leading to hypokalemia, fluid overload, and chronic kidney disease, and patients should be monitored accordingly.

Stimulant Laxatives and Stool Softeners. Stimulant laxatives, such as bisacodyl (Dulcolax) and sennosides, are reasonable short-term, second-line adjuncts to osmotic and bulk laxatives and nonpharmacologic interventions, although few quality studies have assessed long-term effectiveness. In a randomized controlled trial comparing four weeks of oral bisacodyl to placebo, the treatment group experienced an increased number of spontaneous bowel movements from 1.1 per week to 5.2 (compared with 1.9 in the placebo group).40 Another trial found significant improvements in bowel frequency and quality of life in patients receiving four weeks of treatment with senna compared with placebo.41 However, the long-term effects of prolonged stimulant laxative use were not assessed in either trial.40–42

Other Agents. Intestinal secretagogues, such as lubiprostone (Amitiza) and linaclotide (Linzess), are more effective than placebo and should be considered when dietary modifications and osmotic and/or stimulant laxatives are ineffective. Lubiprostone works on intestinal chloride channels to increase intestinal fluid secretion and small intestine stool passage and is approved for chronic constipation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).43,44 Linaclotide and plecanatide (Trulance), guanylate cyclase-c agonists approved by the FDA for chronic constipation, have shown promise in the ability to improve stool frequency, consistency, abdominal discomfort, and straining.45,46 The most common adverse effect leading to discontinuation of these medications is diarrhea. Prucalopride (Motegrity), a serotonin 4 receptor agonist that increases acetylcholine, is also FDA-approved for chronic constipation. However, intestinal secretagogues and prucalopride are considerably more expensive than standard laxatives, and there is no evidence that they are more effective.21

For patients with opioid-induced constipation, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs), such as naloxegol (Movantik), methylnaltrexone (Relistor), and naldemedine (Symproic), are more effective than placebo in decreasing time to defecation and reducing the need for laxative therapy.47 Methylnaltrexone should be used with caution in patients who have intestinal malignancy and should not be used in patients with intestinal obstruction. Adverse effects include abdominal pain and flatulence. The American Gastroenterological Association recommends considering PAMORAs only after traditional laxatives fail.6,21

REFRACTORY CONSTIPATION

When second-line therapies, including stimulant laxatives, have failed, patients should be referred to gastroenterology for further diagnostic testing as depicted in Figure 1.6,11,21 Surgical interventions, such as abdominal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis, are reserved for patients in whom nonsurgical management has been ineffective.6,10

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Mounsey, et al.23; Jamshed, et al.11; and Hsieh.34

Data Sources: PubMed searches were completed using the key terms constipation, evaluation, management, and medications. The searches included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, review articles, and practice guidelines. References from these sources were monitored. The Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and Clinical Evidence were also searched. In addition, references in these resources were searched. Search dates: August 2021 through May 2022.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.