Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(1):52-58

Patient information: See related handout on temporomandibular disorders.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

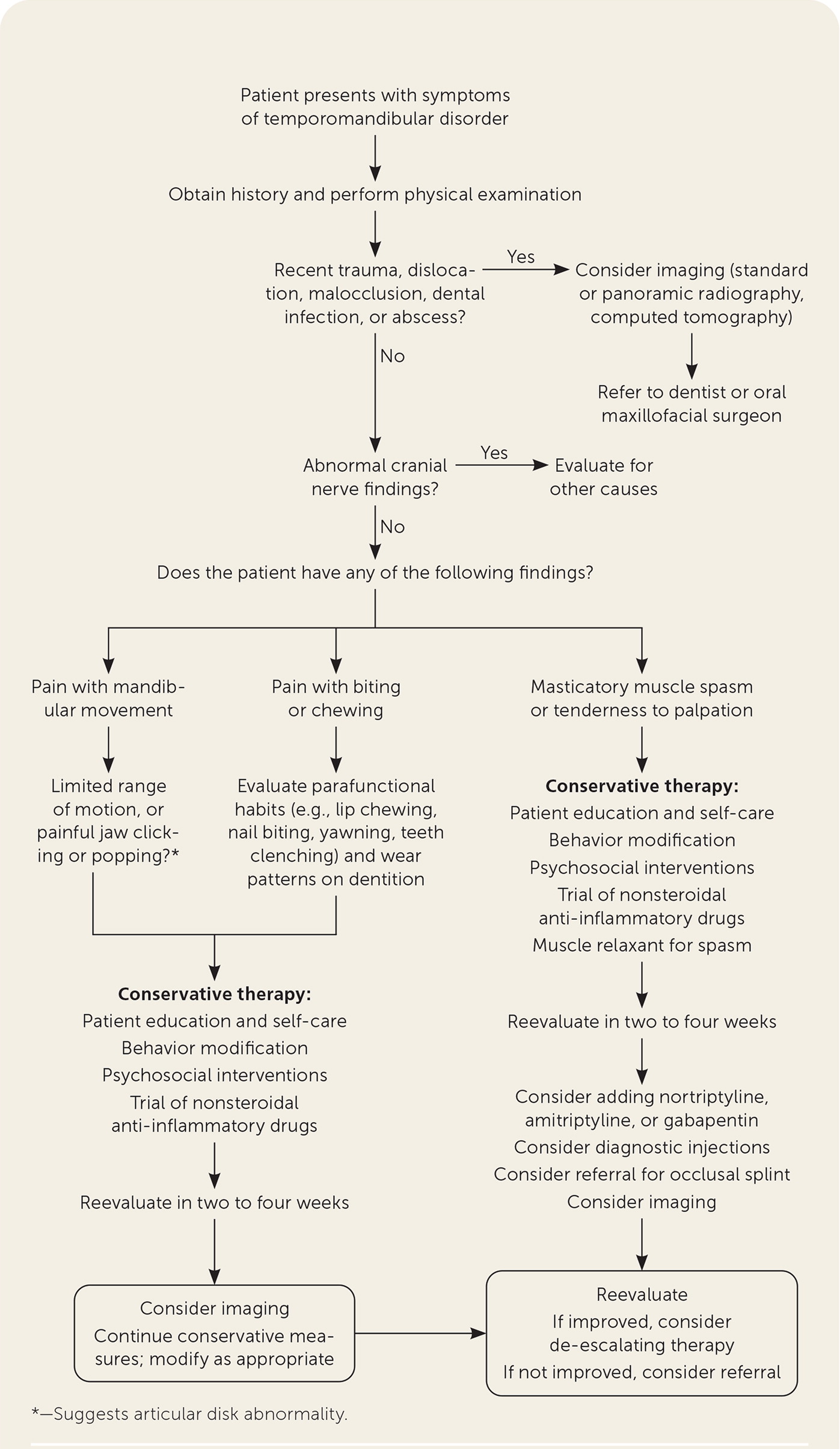

Temporomandibular disorders affect between 5% and 12% of the population and present with symptoms such as headache, bruxism, pain at the temporomandibular joint, jaw popping or clicking, neck pain, tinnitus, dizziness, decreased hearing, and hyperacuity to sound. Common signs on physical examination include tenderness of the pterygoid muscles, temporomandibular joints, and temporalis muscles, and malocclusion of the jaw and crepitus. The diagnosis is based on history and physical examination; however, use of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is recommended if the diagnosis is in doubt. Nonpharmacologic therapy includes patient education (e.g., good sleep hygiene, soft food diet) and physical therapy. Pharmacologic therapy includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclobenzaprine, tricyclic antidepressants, and gabapentin. Injections of the temporomandibular joints with sodium hyaluronate, platelet-rich plasma, and dextrose prolotherapy may be considered, but the evidence of benefit is weak. A referral to oral and maxillofacial surgery is indicated for refractory cases.

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) include conditions that cause pain or dysfunction with the muscles of mastication or the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This rapid evidence review focuses on patient-oriented evidence for managing patients with issues related to the temporomandibular region.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| There is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychological therapy for the treatment of pain or psychological distress associated with temporomandibular disorders.15 | B | Systematic review with meta-analysis of lower quality clinical trials with inconsistent findings |

| Occlusal splints decrease pain and improve mandibular movement.22 | B | Systematic review of lower-quality clinical trials with inconsistent findings |

| Naproxen should be recommended for initial pharmacotherapy of temporomandibular disorders.23,24 The addition of cyclobenzaprine is recommended if there is clinical evidence of muscle spasm.25 | A | Randomized controlled trials of good quality |

| Corticosteroid injections into the temporomandibular joint are no better than arthrocentesis with saline and should be avoided due to potential cartilage damage.30 | B | Systematic review of lower-quality clinical trials with inconsistent findings |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Avoid routinely using irreversible surgical procedures such as braces, occlusal equilibration, and restorations as the first treatment of choice in the management of temporomandibular joint disorders. | American Dental Association |

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The prevalence of TMDs is between 5% and 12%.1

Managing TMDs is estimated to cost $4 billion annually in the United States.1

TMDs often present with comorbid psychopathology (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety) and other comorbid conditions such as chronic pain and fibromyalgia.2

TMDs have a bimodal peak at 21 and 53 years of age with a female-to-male ratio of 3-to-1.3

TMDs occur due to complex interactions involving biomechanical, psychosocial, and genetic factors.4

Causes of TMDs include overuse (e.g., bruxism, nocturnal clenching, spasms), trauma, infection (e.g., herpes zoster, abscess), dental disorders (e.g., caries), and autoimmune diseases.5

TMDs are classified as chronic if they persist for more than three months.6

Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The differential diagnosis for TMDs is summarized in Table 1.7

The differential is extensive but can be classified as intra-articular or extra-articular (Table 2).1,5,6,8

Common symptoms include headache (79%), bruxism (58%), pain at the TMJ (54%), otalgia (52%), jaw popping or clicking (51%), neck pain (51%), tinnitus (37%), dizziness (37%), decreased hearing (36%), and hyperacuity to sound (23%).6,9,10

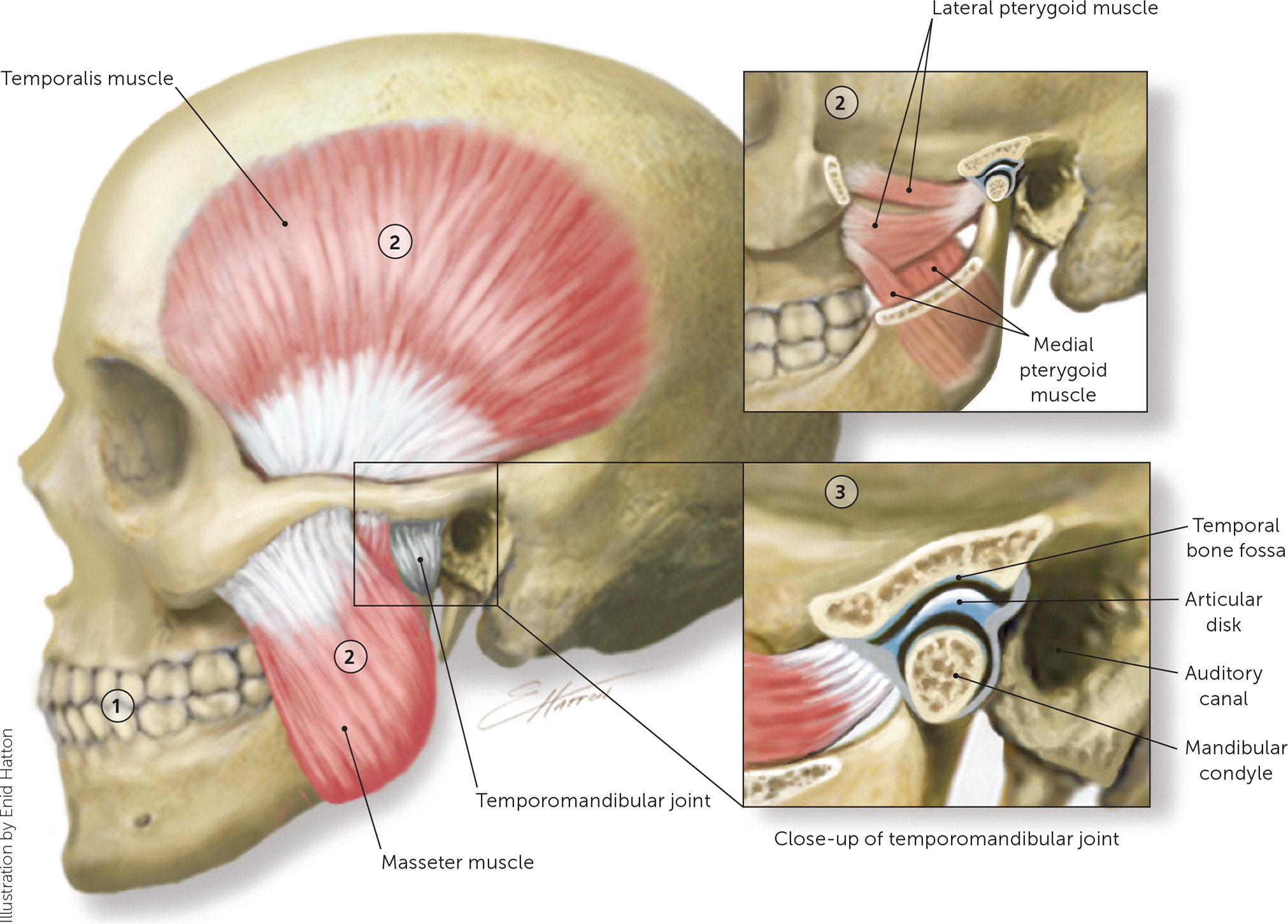

Common signs on palpation include tenderness of the pterygoid muscles, TMJs, temporalis muscles, angle of the mandible, posterior cervical area, and sternocleidomastoid muscle9 (Figure 16).

Other signs include malocclusion with lateral deviations of the jaw on opening and closing, slow or staggered movements of the jaw, inability to open the jaw more than 30 to 35 mm, and worn incisal surfaces of the teeth.9 Clicking, popping, snapping, or locking sensations are common with jaw movement.8 Crepitus is a common finding in patients with degenerative joint disease of the TMJ.5

Consider other diagnoses if there is no pain with jaw movement or the cranial nerve examination is abnormal.5

Validated diagnostic instruments have been published in the past 10 years, such as the Diagnostic Criteria for TMDs, which is divided into Axis 1 (focusing on the TMJ and associated structures) and Axis 2 (assessing for psychosocial comorbidity).5,8

A simple screening method is the TMD Pain Screener tool.11 Although the authors report excellent sensitivity and specificity in a validation study, the design of that study with confirmed cases compared with the healthy pain-free control group inflates the apparent accuracy 8,11 (Table 311).

Patients with jaw trauma or a suspected dental abscess should be sent for dental panoramic tomography and referred to oral and maxillofacial surgery.6

| Idiopathic orofacial pain Burning mouth syndrome Myofascial orofacial pain Primary myofascial pain syndrome Secondary myofascial pain syndrome caused by muscle spasm, myositis, or tendinitis Orofacial pain attributed to disorders of dento-alveolar and anatomically related structures Pain caused by autoimmune disease, cancer, chemotherapy, dental trauma, infection, or radiation therapy Orofacial pain attributed to a lesion or disease of the cranial nerves Glossopharyngeal neuralgia Trigeminal neuralgia | Orofacial pain resembling presentation of primary headache Hemifacial continuous pain with autonomic symptoms Neurovascular orofacial pain Orofacial cluster attacks Orofacial migraine Paroxysmal hemifacial pain Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform facial pain attacks with cranial autonomic symptoms Tension-type orofacial pain Trigeminal autonomic orofacial pain | Temporomandibular joint pain Acute primary Arthritis Chronic primary Degenerative joint disease Disk displacement Primary Secondary Subluxation |

| Disorders | History and examination findings |

|---|---|

| Muscles of mastication (extra-articular) | |

| Muscle spasm Myalgias Myofascial pain Myositis Neoplasm Tendinitis | Neoplasm marked by swelling Pain can refer outside this region Pain with movement and palpation of the muscles of mastication |

| Temporomandibular joint (intra-articular) | |

| Degenerative joint disease (i.e., inflammatory [synovitis, capsulitis] and noninflammatory) | Crepitus with pain on joint palpation |

| Disk derangements (i.e., displacement and perforation | Click, snap, pop with movement Decreased mouth opening Locking sensation |

| Headache due to temporomandibular disorder | Most commonly in temporal region Affected by jaw movement and function |

| Hypermobility | Joint laxity and subluxation |

| Hypomobility (i.e., ankylosis and fibrosis) | Impairment in speech, chewing |

| Infection | Severe fever, chills, pain, and difficulty opening jaw |

| Question | Points |

|---|---|

| In the past 30 days, how long did any pain last in your jaw or temple area on either side? | |

| No pain | 0 |

| Pain comes and goes | 1 |

| Pain is always present | 2 |

| In the past 30 days, have you had pain or stiffness in your jaw on awakening? | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| In the past 30 days, did the following activities change any pain (make it better or worse) in your jaw or temple area on either side? | |

| Chewing hard or tough food | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| Opening your mouth or moving your jaw forward or to the side | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| Jaw habits such as holding teeth together, clenching, grinding, or chewing gum | - |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| Other jaw activities such as talking, kissing, or yawning | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Imaging is indicated when the diagnosis of TMDs is in doubt or if conservative treatment is ineffective. Motor or sensory deficits, suspicion of osteoarthritis, palpable mass, or atypical symptoms indicate prompt imaging.12 It is important to note that not all imaging centers have the necessary equipment and expertise.

The imaging modalities include dental panoramic tomography, cone-beam computed tomography (CT), multidetector CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasonography.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred modality for evaluating soft tissue derangements such as disk displacement at the TMJ.

Cone-beam CT is the preferred imaging modality for assessing bony anomalies at the TMJ due to a lower radiation dose and better spatial resolution than conventional CT.

Plain radiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and CT are appropriate for joint subluxation.12

High-resolution ultrasonography may be useful for evaluating disk displacement and effusion, but it is rarely used because the TMJ is difficult to image.

Blood tests are not routinely recommended.

Treatment

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY AND ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT

Supportive patient education and self-management strategies are beneficial to patients.13 Self-management strategies may include optimal head posture, sleep hygiene, avoidance of triggers (e.g., nail biting, gum chewing, clenching, grinding), heat or ice packs, a soft food diet, and home exercises.14

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychological therapy (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy, behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness) for the treatment of pain or psychological distress associated with TMDs.15

Physical therapy may improve pain and function, but the evidence is unclear.16,17 Components may include electrotherapy, therapeutic exercises, postural awareness, muscular relaxation, and massage. Most studies have used manual therapy in which physical therapists use their hands to decrease pain and joint dysfunction through direct pressure on muscles and joints.

ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES AND SPLINTS

Dry needling and wet needling with substances (e.g., onabotulinumtoxinA, lidocaine, collagen, platelet-rich plasma, morphine) within masticatory muscles decreased pain in one systematic review; however, there is a need for additional high-quality clinical trials using an active control group receiving sham therapy.18

Acupuncture relieved myofascial pain in one retrospective cohort study, but there was no comparison group. Additional studies using an active control group receiving sham therapy are needed before acupuncture can be recommended.19

Low-level laser therapy had positive effects on pain relief in 18 out of 30 studies in one systematic review; however, due to the variability in study protocols, the magnitude of benefit, and inconsistent results, additional trials are needed before low-level laser therapy can be recommended.20

A meta-analysis found that glucosamine was as effective as ibuprofen at 12 weeks for pain control and maximal mouth opening, but only one out of three studies included was high quality, and neither glucosamine nor ibuprofen outperformed placebo.21

A systematic review of 11 studies with between 12 and 96 patients each found that occlusal splints decrease pain and improve mandibular movement in the short to medium term, but long-term studies are needed.22

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

The recommended pharmacologic therapy for TMDs is listed in Table 4.23–28

A systematic review of four randomized controlled trials demonstrated that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) decreased pain; however, due to the variability in study protocols, it concluded with only moderate certainty that this improvement is clinically meaningful.23

Naproxen, 500 mg twice per day, demonstrated significant pain relief and increased range of motion in patients with TMDs compared with placebo (number needed to treat = 2.2 for a 50% or greater pain reduction).24

The overall recommendation for NSAIDs is to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration.

Cyclobenzaprine, 10 mg taken at bedtime for muscle spasms for three weeks, decreased pain vs. placebo based on one network meta-analysis.25

Amitriptyline, 25 mg at bedtime for two weeks, reduced pain by 34% vs. 14% for placebo. Nortriptyline may be substituted if the patient experiences unacceptable anticholinergic adverse effects.27

Gabapentin decreased pain at 12 weeks in a randomized controlled trial vs. placebo, with dosages ranging from 300 to 4,200 mg per day. The reduction was 51% vs. 24% for placebo.28

Propranolol extended release, 60 mg twice daily for nine weeks, decreased TMD-related pain for patients with migraines, but not in patients without migraines (number needed to treat = 6 to decrease facial pain by 50% or greater vs. placebo).29

Diazepam demonstrated effectiveness in one small study but should be avoided because of the risk of addiction and modest improvement vs. placebo.26

Opioids are not recommended due to the high risk of dependence and the availability of other treatment options.6

| Medication/dosage | Outcome | Type of study | Common adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naproxen, 500 mg twice daily | Decreased pain and improved range of motion vs. placebo* | RCT | Dyspepsia, headache, nausea, rash, and dizziness |

| Cyclobenzaprine, 10 mg at bedtime | Decreased pain vs. placebo* | Systematic review of two RCTs | Dizziness, dry mouth, and drowsiness |

| Amitriptyline, 25 mg at bedtime | Decreased pain 34% vs. 14% for placebo* | RCT | Dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, and constipation |

| Gabapentin, 300 to 4,200 mg per day | Decreased pain 51% vs. 24% for placebo* | RCT | Dizziness, drowsiness, and fatigue |

THERAPEUTIC INJECTIONS

Evidence for intra-articular corticosteroid injections is unclear; therefore, they are not recommended because of the potential for destruction of articular cartilage.30

A consistent benefit from intra-articular injections of sodium hyaluronate, corticosteroid, and platelet-rich plasma was not identified over arthrocentesis alone, which suggests additional study is needed to determine if these treatments should be recommended.31–35

One systematic review found intramuscular onabotulinumtoxinA injections decrease myalgias but not arthralgias in TMDs.33

Intra-articular injections with dextrose prolotherapy demonstrated decreased pain in one systematic review with meta-analysis.34

Intra-articular injection of stem cells demonstrated decreased pain and improved maximal mouth opening, but the evidence was weak and at high risk of bias.36

SURGERY

Although most patients with a TMD can be treated satisfactorily without surgery, patients with fracture of the TMJ due to trauma, and those with severe pain or joint dysfunction lasting more than three to six months, should be referred to oral and maxillofacial surgery or a dentist specializing in TMDs.6 However, evidence suggests that surgical correction of a TMD has a high failure rate and should be avoided if possible because it may worsen pain and dysfunction.37

Prognosis

For many patients, TMDs remit over time without treatment.

Chronic TMDs can be challenging to treat. For patients with a chronic TMD, referral to clinicians specializing in treating TMDs is strongly recommended.37

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Buescher38 and Gauer and Semidey.6

Data Sources: A search was completed in Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, and PubMed using the key words temporomandibular joint, temporomandibular disorders, TMJ, TMD, and bruxism. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and systematic reviews. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sources were reviewed for epidemiology data. Search dates: January, March, April, July, August, and November 2022.