Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(1):42-51

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

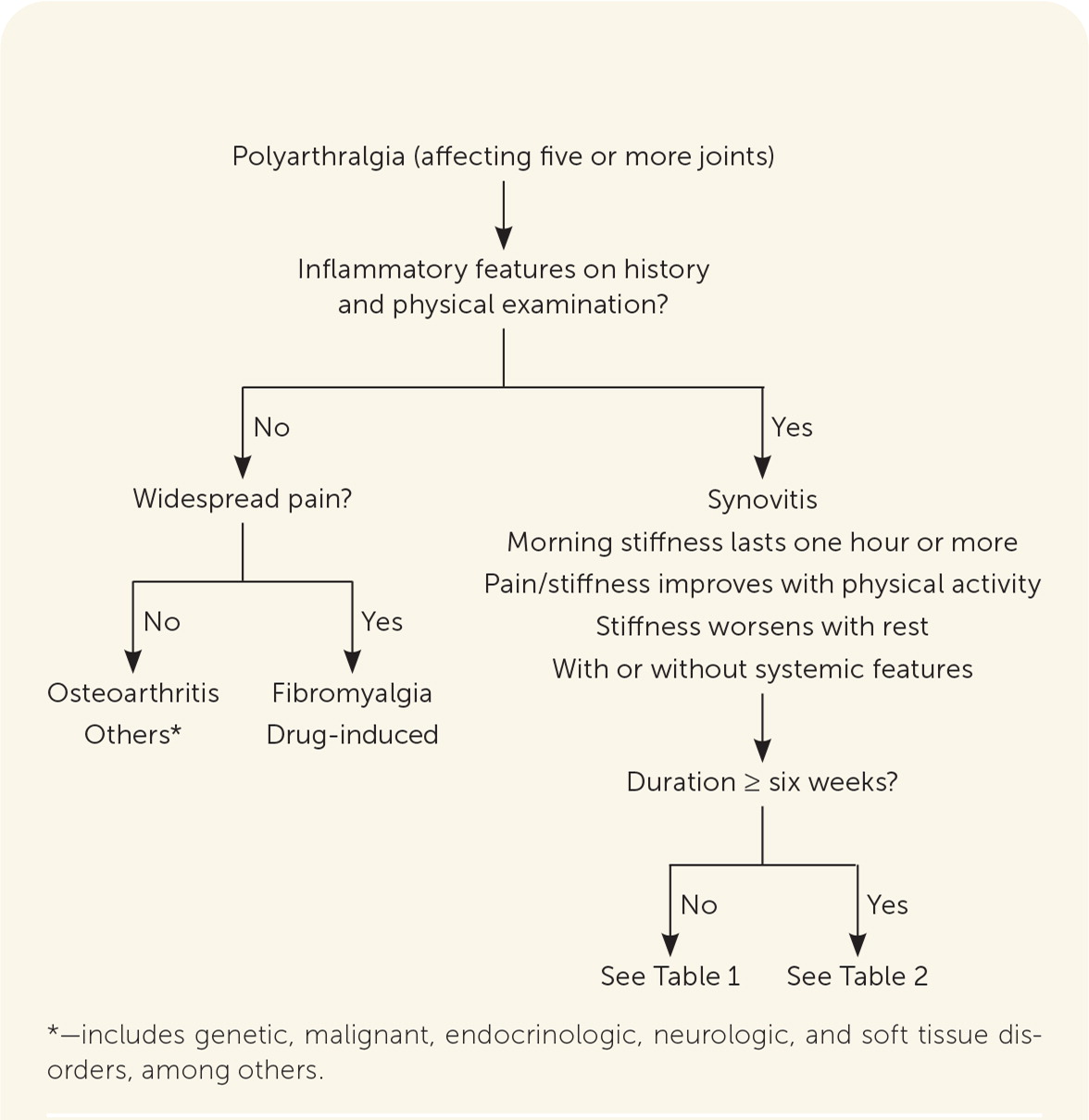

Polyarticular joint pain involves five or more joints and can be inflammatory or noninflammatory. Two of the most common causes of chronic polyarthritis are osteoarthritis, especially in older patients, and rheumatoid arthritis, which affects at least 0.25% of adults worldwide. The initial evaluation should include a detailed history of the patient's symptoms, with a focus on inflammation, location of pain, duration of symptoms, the presence of systemic symptoms, and any exposures to pathogens that could cause arthritis. Redness, warmth, or swelling in a joint is suggestive of synovitis and joint inflammation. A systematic approach to the physical examination that assesses for a pattern of joint involvement and presence of synovitis can help narrow the differential diagnosis. Laboratory tests, joint aspiration, and imaging studies should be used to confirm a suspected diagnosis. Rheumatoid factor and cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody tests are helpful when there is concern for rheumatoid arthritis. Although magnetic resonance imaging is highly sensitive in identifying erosive bony changes and inflammation, conventional radiography remains the standard for the initial imaging evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis. Point-of-care musculoskeletal ultrasonography can also be a useful tool to detect findings that support a diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis.

Arthritis, defined as joint inflammation, affects nearly 1 in 4 adults in the United States.1 Two of the most common causes of chronic polyarthritis are osteoarthritis, especially in older patients, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which affects at least 0.25% of adults worldwide.2 Most people in the United States with arthritis have osteoarthritis, which is a noninflammatory condition. Although inflammatory arthritis is uncommon, studies show that adults presenting to primary care with musculoskeletal symptoms often report joint pain, stiffness, or swelling that could be consistent with inflammatory arthritis.3 The diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis in the primary care setting is challenging. When a patient presents with polyarticular pain (involving five or more joints), a systematic approach to the diagnosis including history, physical examination, laboratory analysis, and imaging is critical because the diagnosis is rarely made by any single measure.4

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not test for Lyme disease as a cause of musculoskeletal symptoms without a history of exposure and appropriate examination findings. | American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Pediatrics – Section on Rheumatology |

History

INFLAMMATION

The presence of inflammation in multiple painful joints largely differentiates inflammatory arthritis (common etiologies include RA, gout, and chronic calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease [pseudogout]) from osteoarthritis. Duration of symptoms can help narrow the differential diagnosis (Figure 1, Table 1,5,6 and Table 25,7–10 ). Inflammation can further be assessed by asking the patient about swelling, redness, and warmth.11 Additional evidence of joint inflammation includes prolonged morning stiffness (one hour or more), pain at night, or gelling phenomenon (stiffness after inactivity).11

| Cause | Distinguishing extra-articular and systemic features |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | Gonorrhea – bacteremic spread occurs in 0.5% to 3% of infected patients causing arthritis-dermatitis syndrome or purulent arthritis; rash, if present, is typically short-lived, painless pustules located on the distal extremities, often with only two to 10 lesions present Infectious endocarditis – systemic symptoms including fever/chills and weight loss; heart murmur in 85% of patients Lyme disease – associated with erythema chronicum migrans (bull's eye rash) Meningitis – arthritis is rare in meningitis; flulike symptoms, stiff neck, photophobia, rash Rheumatic fever – arthritis is an early manifestation; arthritis is more common in teens and young adults (80%) than in children (65%) |

| Crystalline arthritis | Gout – rare to have extra-articular manifestations in acute/early disease Pseudogout |

| Early rheumatic disease | Inflammatory bowel disease–associated arthritis Polymyalgia rheumatica Psoriatic arthritis Reactive arthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Sarcoidosis | Cutaneous manifestations (e.g., erythema nodosum) occur in about 25% of patients and are often an early finding; swelling usually occurs in the soft tissue around the joints and not in the joints themselves; hilar lymphadenopathy |

| Virus | HIV – flulike illness, pruritic erythematous rash, mouth ulcers, swollen lymph nodes Parvovirus B19 – slapped cheeks appearance, fever, rhinitis, headache Viral hepatitis – jaundice, abdominal pain, elevated liver function test results |

| Other | Autoinflammatory disease Inflammatory myositis Other spondyloarthropathies Sjögren syndrome Systemic sclerosis Systemic vasculitis |

| Diagnosis | Distinguishing extra-articular and systemic features | Age and sex predominance |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (pseudogout) | Associated with hemochromatosis, hyperparathyroidism, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia | Older adults, no sex predominance |

| Gout | Subcutaneous tophi possible in joints, ears, olecranon bursae, finger pads, tendons | Men 30 to 60 years of age |

| Inflammatory bowel disease– associated arthritis | History of inflammatory bowel disease, weight loss, fatigue | No specific age or sex |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | Aching and weakness of the shoulder girdle; flulike symptoms | More common in women than men; onset typically between 50 and 70 years of age |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Psoriatic skin lesions (papular erythematous plaques topped with a silvery scale), nail lesions (including pits and onycholysis) | No specific age or sex |

| Reactive arthritis | Often associated with gastrointestinal or genitourinary infections | No specific age or sex |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Can involve dermatologic (nodules, lymphedema); ophthalmologic (uveitis); pulmonary (interstitial lung disease, effusion); cardiovascular (effusion, arrhythmias); gastrointestinal (xerostomia); neurologic (peripheral nerve entrapment); and hematologic (lymphadenopathy, leukopenia) systems | Women 30 to 60 years of age Men older than 60 years |

| Sjögren syndrome | Sicca symptoms | Women 30 to 50 years of age |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Arthritis in proximal interphalangeal joints and knees; variable presentation | Young women of child-bearing age |

| Others (autoinflammatory disease, inflammatory myositis, other spondyloarthropathies, systemic sclerosis, systemic vasculitis) | — | — |

Although inflammation may be localized to the joints, in rheumatic diseases, extra-articular or systemic features are often present. Rashes are a common extra-articular finding that can provide pathognomonic support for a diagnosis such as plaques in psoriasis or erythema chronicum migrans in Lyme disease. Constitutional findings such as fatigue, fever, malaise, or weight loss are also common. Other possible extra-articular features include dry eyes or mouth, dysphagia, gastrointestinal symptoms, interstitial lung disease, lymph-adenopathy, mucosal ulceration, muscle weakness, ocular inflammation, photosensitivity, pleural or pericardial effusions, and Raynaud phenomenon11 (Table 15,6 and Table 25,7–10). Patients with more diffuse pain and muscle rather than joint involvement may have fibromyalgia (Figure 1).

DURATION

The differential diagnosis can vary depending on the duration of symptoms; however, there is no consensus on the time frame for acute vs. chronic arthritis. With that in mind, using a symptom duration of six weeks or more is a reasonable cutoff for defining chronic symptoms because that is used in the classification criteria for RA, which is the most common autoimmune inflammatory arthritis in adults.12–14 However, if the duration of symptoms is less than six weeks but the clinical scenario is suggestive of an early inflammatory polyarthritis, referral to a rheumatologist should not be delayed because early treatment in these cases can affect long-term outcomes.15

EXPOSURES

A detailed history should include questions about any potential exposures as a cause of joint pain.16 Travel history may reveal potential contact with ticks carrying Lyme disease or other regional pathogens.17 Sexual or blood exposure history can identify risk for HIV, hepatitis C infection, or other sexually transmitted infections that could cause arthropathy.16 Review of medication use, such as certain antimicrobials, dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitors, and isotretinoin, can reveal potential causes of vasculitis or drug-induced syndromes.18 Additionally, occupational history may lead to concern for chemical exposures and related conditions such as lead toxicity.19

JOINT INVOLVEMENT

Inflammatory arthritis tends to have specific joint predilection depending on the underlying etiology (Table 36,20). Assessing the pattern of joint involvement, including location, symmetry, and number of joints involved, helps narrow the differential diagnosis.5 This may be complicated by overlap between disease processes; therefore, identifying unique factors is paramount. For instance, RA is typically a symmetrical inflammatory polyarthritis with a predilection toward the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, whereas spondyloarthropathies (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease–associated arthritis) tend to be more asymmetrical and affect only a few joints.

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Psoriatic arthritis | IBD–associated arthritis | Polyarticular gout | CPPD (pseudo gout) | Polymyalgia rheumatica | Reactive arthritis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal inter phalangeal | X | X | |||||

| Proximal interphalangeal | X | X | X | X | |||

| Metacarpophalangeal | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Wrist | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Elbow | X | X | X | X | |||

| Glenohumeral | X | X | X | ||||

| Cervical | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Vertebral | X | X | X | ||||

| Sacroiliac | X | X | X | ||||

| Hip | X | X | X | X | |||

| Knee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ankle | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Midfoot | X | X | |||||

| Metatarsophalangeal | X | X | X | X* | |||

| Toe interphalangeal | X | X | X | ||||

| Pelvic girdle | X† | ||||||

| Shoulder girdle | X† | ||||||

| Enthesitis | X | X | X | ||||

| Dactylitis | X | X | X |

Physical Examination

Assessment for warmth, redness, and swelling in addition to joint pain is important on examination of a joint. Redness is frequently seen with crystalline and infectious arthritis. Patients with arthritis may also have limited range of motion in the joint as well as decreased muscle strength around the joint. Patients with joint inflammation may hold the joint in partial flexion to reduce the joint volume and thus pain in the joint.5

Spondyloarthropathies are more often associated with enthesitis, dactylitis, and inflammatory low back pain compared with RA.7,8 Enthesitis indicates inflammation at the site where a tendon or ligament attaches to bone (an enthesis).21 Swelling, warmth, and pain may be noted on examination. Dactylitis, or sausage digit, refers to diffuse fusiform swelling of a digit.22 In acute cases, there is redness and pain in addition to the swelling. Dactylitis most commonly occurs in the fingers and in the third and fourth toes in psoriatic arthritis.8

SMALL JOINTS

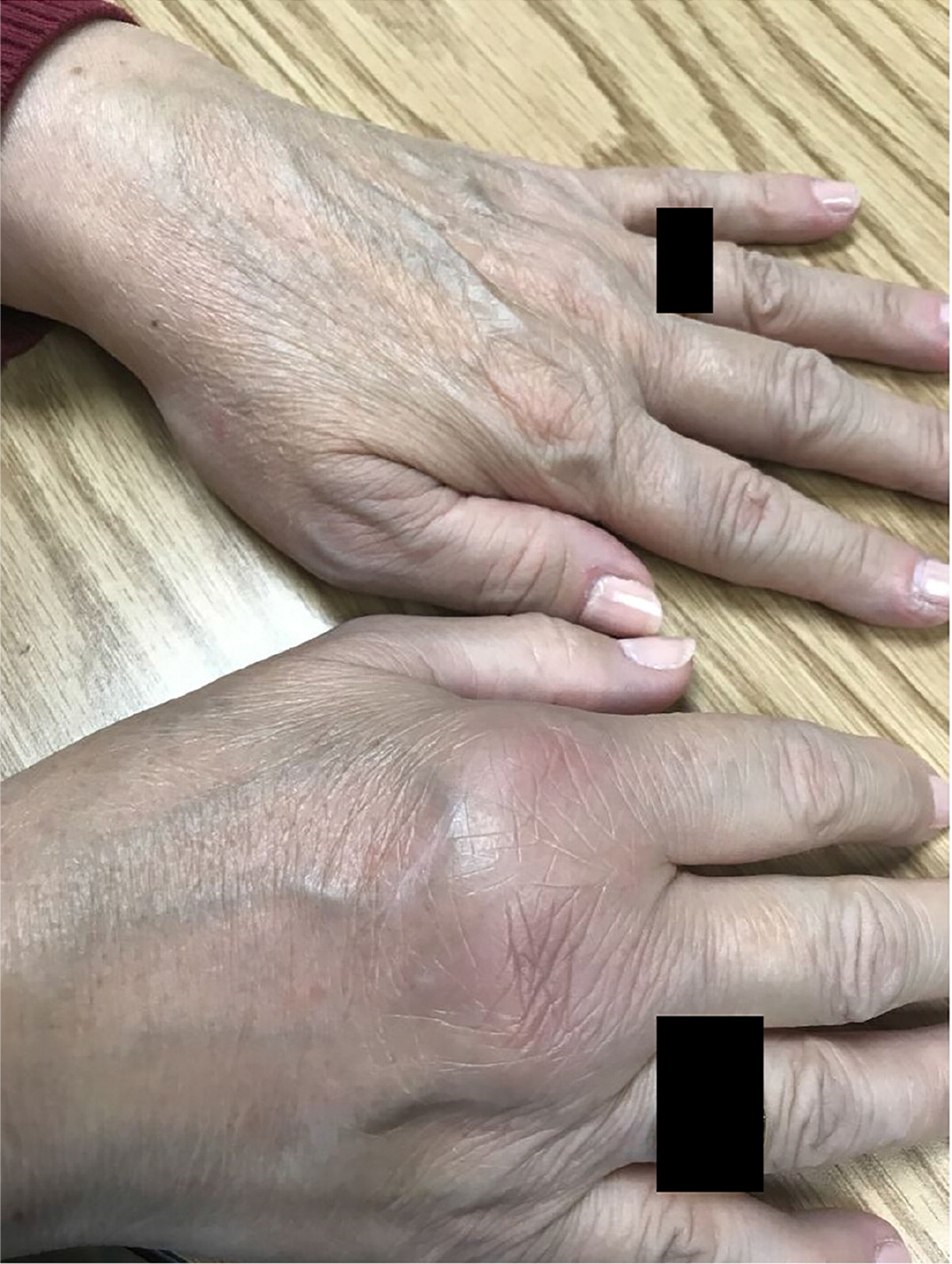

Many polyarticular processes involve small joints (i.e., fingers and toes or wrists in the case of RA), and a systematic approach to their evaluation is prudent. The initial inspection should assess for evidence of swelling, erythema, synovitis, or dactylitis. The presence of skin findings such as psoriatic plaques or dystrophic nails (e.g., nail pitting in psoriatic disease) should be noted. The fingers should be examined for bony enlargement at the proximal interphalangeal joints (Bouchard nodes) and distal interphalangeal joints (Heberden nodes) that indicate osteoarthritis. Rheumatoid nodules are often found where there are pressure points. Tophi are found in the soft tissues, including the helix of the ear and around articular structures. On palpation, synovitis will consist of boggy swelling over the joint23 (Figure 2). Synovitis of the metacarpophalangeal joints can be detected on ballottement with a two-finger approach, which detects a dorsal boggy swelling between the palpating fingers24 (Figure 3). Passive and resisted active range of motion tests can be performed to help localize pathology to intra-articular or extra-articular structures, respectively.11

LARGE JOINTS

The approach to large joints should begin with inspection, assessing for erythema, swelling, skin changes (e.g., overlying cellulitis, which might suggest an underlying septic joint), or obvious deformity.25 Warmth, signs of periarticular involvement, or evidence of effusion or bursitis can be detected with palpation. Warmth in a joint is best assessed using the back of the examining hand. In a patient with no joint concerns, as the hand is moved from the shin to the patella, the examiner will note that the knee joint is cooler than the rest of the leg. Examination of strength and active and passive range of motion can help assess functional impairment. Special tests such as the log roll in the hip examination (passive internal and external rotation of the extended leg in a relaxed, supine patient) can help evaluate hip pathology (e.g., septic arthritis), and the Lachman test in the knee examination can evaluate for anterior cruciate ligament injury, thus narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Workup

LABORATORY TESTING

The diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis is largely based on the history and physical examination, with laboratory findings or biomarkers serving to confirm the clinical impression.5 For example, in patients with musculoskeletal symptoms, Lyme disease testing should be performed only if there is a reported history of exposure or other consistent symptoms are present such as an erythema chronicum migrans (i.e., bull's eye rash).26

Although elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level are not diagnostically specific, they can be helpful to suggest inflammatory arthritis in the correct clinical context, for example, when synovitis and erythema are present on physical examination.11 Conversely, even in septic arthritis, the lack of elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level is not sufficient to rule out infection if there is clinical concern.27

Rheumatoid factor is not specific for RA and is present in other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.28 Approximately 30% of people with established RA test negative for rheumatoid factor,7 and rheumatoid factor is present in more than 25% of healthy people older than 85 years.28 Cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody testing has a higher positive predictive value for RA than rheumatoid factor.29 When suspicion is high for RA, rheumatoid factor, cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody,7 erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein tests should be ordered.

Likewise, antinuclear antibodies are a hallmark of many rheumatic conditions, including Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, and systemic sclerosis, but they may also be present in many nonrheumatic diseases, such as HIV and hepatitis C infection, autoimmune thyroid diseases, and autoimmune liver diseases.30 Low titer antinuclear antibodies (1:40) are present in approximately 30% of healthy people.31 Presence of antinuclear antibodies itself, regardless of titer, does not necessarily indicate that an autoimmune disease is present.

Although psoriatic arthritis develops in about 24% of people with psoriasis, there are no specific validated tests for psoriatic arthritis.32

JOINT ASPIRATION

In septic arthritis, which more often affects only one joint, Gram stain with culture of synovial fluid is the standard method for diagnosis although cultures may only be positive in up to 82% of cases.33 A higher white blood cell count in synovial fluid increases the likelihood ratio of septic arthritis; patients with a synovial white blood cell count 25,000 per μL (25 × 109 per L) or greater have a likelihood ratio of 2.9, compared with a likelihood ratio of 28.0 for those with a synovial white blood cell count greater than 100,000 per μL (100 × 109 per L).33 In cases of noninflammatory arthritis, the white blood cell count typically ranges from 200 to 2,000 per μL (0.2 to 2 × 109 per L). Reactive arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis that typically occurs within one month of an infection (often genitourinary or gastrointestinal).9 However, unlike septic arthritis, the synovial fluid in reactive arthritis is sterile.

Polyarticular gout can present a diagnostic dilemma, especially when involving atypical joints.34 It is often associated with comorbidities and untreated disease.35 Careful attention to a history of intermittent arthritis and a physical examination for tophi are imperative.36 In gout and pseudogout, the presence of crystals in synovial fluid is considered the diagnostic standard. Therefore, effort should be made to obtain a synovial fluid specimen for analysis. Absence of crystals on analysis does not rule out gout or pseudogout if there is high clinical suspicion. In classic monoarticular gout, a clinical prediction rule can be used for diagnosis when aspiration is not possible37,38 (https://www.mdcalc.com/acute-gout-diagnosis-rule).

IMAGING

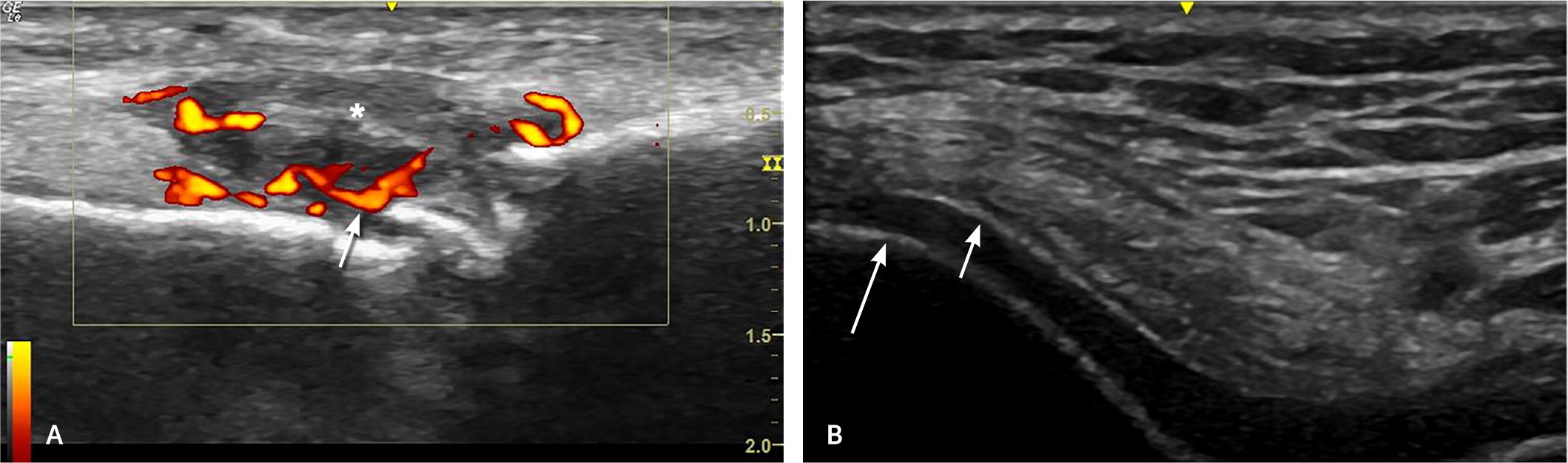

Imaging for polyarticular pain can be helpful in supporting a diagnosis. It is important to view imaging as an extension of the history and physical examination, not a replacement for it. Classically, radiography has been the preferred standard for imaging and can show erosive changes from RA39 (Figure 4). It is commonly used because it is cost-effective and widely available. Whereas radiography is not as sensitive to the early stages of rheumatologic disease,40 ultrasonography can detect early changes and assess the surrounding synovium and soft tissue structures41 (Figure 5). Other benefits of ultrasonography are cost-effectiveness and lack of radiation.41 Magnetic resonance imaging is less commonly used but is highly sensitive for erosive changes and inflammation, in addition to being able to evaluate surrounding tissue,42 but its use is limited by availability and cost.

Radiographic findings suggestive of osteoarthritis include marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cysts, and joint space narrowing (often asymmetrical in primary osteoarthritis).43 Early changes of RA include soft tissue swelling and juxta-articular osteopenia. The earliest erosions in the metacarpophalangeal joints occur where the joint capsule synovium directly contacts the bone, often referred to as a marginal erosion44 (Figure 4). Late changes include diffuse osteoporosis, large subchondral erosions, uniform joint space loss, and joint subluxation.45

Although the clinical findings of psoriatic arthritis can be similar to RA, some findings on radiography are distinct. Marginal erosions can be seen initially but may progress to also involve the central portion of the joint,46 leading to a pencil-in-cup erosion (erosion/osteolysis causing a pointed phalanx that articulates with a cup- or saucer-shaped erosion on an adjacent phalanx). In addition to destructive changes, bone proliferation can also occur, which may be juxta-articular or along the shaft of the bone.46,47

For patients with tophaceous or polyarticular gout, well-defined (rat bite) erosions with sclerotic margins and overhanging edges may be visible on radiography, although findings in early disease are often minimal or absent.10 Gout findings on ultrasonography include an abnormal hyperechoic band overlying the superficial margin of hyaline cartilage (double contour sign; Figure 5), as well as tophi, monosodium urate aggregates, and erosions.48

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Pujalte and Albano-Aluquin49 and Richie and Francis.50

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the key terms polyarticular arthritis, differential diagnosis, clinical laboratory techniques, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, septic arthritis, reactive arthritis, lupus, pseudogout, psoriasis, gonorrhea, and Lyme disease. ClinicalKey was searched using the term osteoarthritis. Essential Evidence Plus was searched using the terms osteoarthritis, septic or pyogenic, and polyarthritis. Search dates: July 2021, January 2022, and September 22, 2022.

The authors thank Karen McMullen of the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Library for her assistance with the literature search and in procuring articles. The authors also thank Dr. James Fant and Dr. Mark Greenberg from Prisma Health Rheumatology for their review and edits to the manuscript.