Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(4):397-405

Patient information: See related handout on leukemia.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Leukemia is caused by an abnormal proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. The four general subtypes are acute lymphoblastic, acute myelogenous, chronic lymphocytic, and chronic myelogenous. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia primarily occurs in children, whereas the other subtypes are more common in adults. Risk factors include certain chemical and ionizing radiation exposures and genetic disorders. Common symptoms include fever, fatigue, weight loss, joint pain, and easy bruising or bleeding. Diagnosis is confirmed with bone marrow biopsy or peripheral blood smear. Hematology-oncology referral is recommended in patients with suspected leukemia. Chemotherapy, radiation, targeted molecular therapy, monoclonal antibodies, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are common treatments. Complications from treatment include serious infections from immunosuppression, tumor lysis syndrome, cardiovascular events, and hepatotoxicity. Long-term sequelae in leukemia survivors include secondary malignancies, cardiovascular disease, and musculoskeletal and endocrine disorders. Five-year survival rates are highest in younger patients and those diagnosed with chronic myelogenous or chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Leukemia is one of the most common malignancies in childhood, but it also often occurs in adults. It is caused by disruptions in the normal cell regulatory process that leads to uncontrolled proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow. From 2015 to 2019, the age-adjusted incidence of leukemia in the United States was 14.1 per 100,000 people per year.1 In the past decade, the incidence of leukemia has been decreasing while survival rates have been increasing due to advancements in diagnosis and treatment.1 The four general leukemia subtypes are acute lymphoblastic, acute myelogenous, chronic lymphocytic, and chronic myelogenous. Primary care physicians should be familiar with common presentations, initial diagnostic evaluation, principles of therapy, and long-term sequelae in survivors.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not perform baseline or routine surveillance computed tomography in patients with asymptomatic, early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. | American Society of Hematology |

Risk Factors

Many leukemia cases do not have an identifiable cause, but people exposed to ionizing radiation, such as atomic bomb survivors and patients receiving chemoradiation therapy for other cancers, have an increased risk of developing acute and chronic myelogenous leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.2,3 Individuals exposed to Agent Orange are at higher risk of developing chronic lymphocytic leukemia.4 Cumulative exposure to ionizing radiation from computed tomography increases the risk of leukemia, especially in children, although the risk is small.5 In children younger than five years, the incidence of leukemia is 1 in 5,250 head scans, whereas the incidence in children 10 to 14 years of age is 1 in 21,160 head scans.6

Long-term exposure to benzene, a chemical found in tobacco smoke, motor vehicle exhaust, and some pesticides, is a known risk factor for leukemia, especially acute myelogenous leukemia.7 Using hair dye does not appear to increase the risk of leukemia.8 People with genetic disorders, including Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, and Fanconi anemia, are at higher risk of developing acute leukemia.2,3 About 30% of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome will develop a secondary leukemia, most likely acute myelogenous leukemia.2 Patients with hepatitis C virus infection have a higher incidence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.4 Obesity is a risk factor for leukemia and adversely affects overall survival.9,10

Clinical Presentation

ACUTE LEUKEMIA

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia predominately occurs in childhood, with 80% of cases occurring in children younger than five years.3 Common symptoms include fever (49% to 57%), weight loss (26% to 31%), pallor (28% to 46%), fatigue (45% to 64%), and easy bruising or bleeding (10% to 43%).11 Some children present with leg and back pain (21% to 59%).12 Up to 60% of children have palpable hepatosplenomegaly, and 41% have lymphadenopathy.13 Cranial nerve neuropathies and meningeal involvement are less common.3 Approximately 6% of children are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.13

Acute myelogenous leukemia is the most common acute leukemia in adulthood, although 20% of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases are in adults older than 50 years. Common symptoms of acute myelogenous leukemia include fever, fatigue, and unintentional weight loss.2,3 Some patients present with anemia-related symptoms, including shortness of breath and pallor.2,3 If thrombocytopenia is present, patients may exhibit conjunctival or retinal hemorrhage, petechiae, oral bleeding, or easy bruising.2,3 Hepatosplenomegaly occurs in approximately 20% of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia but is rarely seen in acute myelogenous leukemia.2,3 Gum infiltration may occur with acute myelogenous leukemia.2 Meningeal infiltration and cranial neuropathies are uncommon in acute myelogenous leukemia but occur in about 5% to 8% of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.2,3

CHRONIC LEUKEMIA

Chronic leukemia primarily affects adults, and 70% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia are older than 65 years.4 Approximately one-half of patients are asymptomatic and diagnosed after an incidentally identified leukocytosis.4,14 Constitutional symptoms, including fever, fatigue, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss, are more common in chronic myelogenous leukemia.14 Although hepatosplenomegaly and palpable lymphadenopathy are common in chronic myelogenous and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, splenomegaly is more prevalent in chronic myelogenous leukemia (46% to 76%) and may lead to early satiety, anemia, and platelet dysfunction.4,14 Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of leukemia subtypes.15

| Subtype | Description | Groups affected | Common features | Five-year survival rates by age (years)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | > 20% lymphoblasts on bone marrow aspirate | Children and young adults (60% are diagnosed before 20 years of age) | Symptoms: easy bruising or bleeding, fatigue, fever, joint pain, pallor Signs: hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy | < 20: 87% 50 to 64: 30% ≥ 65: 15% |

| Acute myelogenous leukemia | > 20% myeloblasts on peripheral blood smear or bone marrow aspirate; Auer rods on peripheral smear | Adults (median age of diagnosis is 68 years) | Symptoms: central nervous system palsies, fever, pallor, thrombocytopenia Signs: flow murmur, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy (less common) | < 50: 55% 50 to 64: 30% ≥ 65: 7% |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | ≥ 5,000 per μL (5 × 109 per L) monoclonal B lymphocytes on peripheral blood smear | Older adults (70% of new cases diagnosed after 65 years of age) | Symptoms: asymptomatic (70%) Signs: hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy | < 50: 93% 50 to 64: 91% ≥ 65: 80% |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL1 fusion gene) | Adults | Symptoms: asymptomatic (50%) Signs: Splenomegaly (46% to 76%) | < 50: 86% 50 to 64: 77% ≥ 65: 42% |

Evaluation and Diagnosis

If leukemia is suspected, the initial workup should include a complete blood count with differential. Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia can occur in early stages of acute leukemia.16,17 Other useful laboratory tests include a comprehensive metabolic panel, liver function tests, and coagulation studies. Uric acid, phosphorous, and lactate dehydrogenase levels can be used to assess for tumor lysis syndrome in patients undergoing leukemia treatment.16–21 Radiography should be considered for joint pain. Urinalysis, blood and urine cultures, and chest radiography should be performed to evaluate for infection in patients who are ill-appearing and febrile.

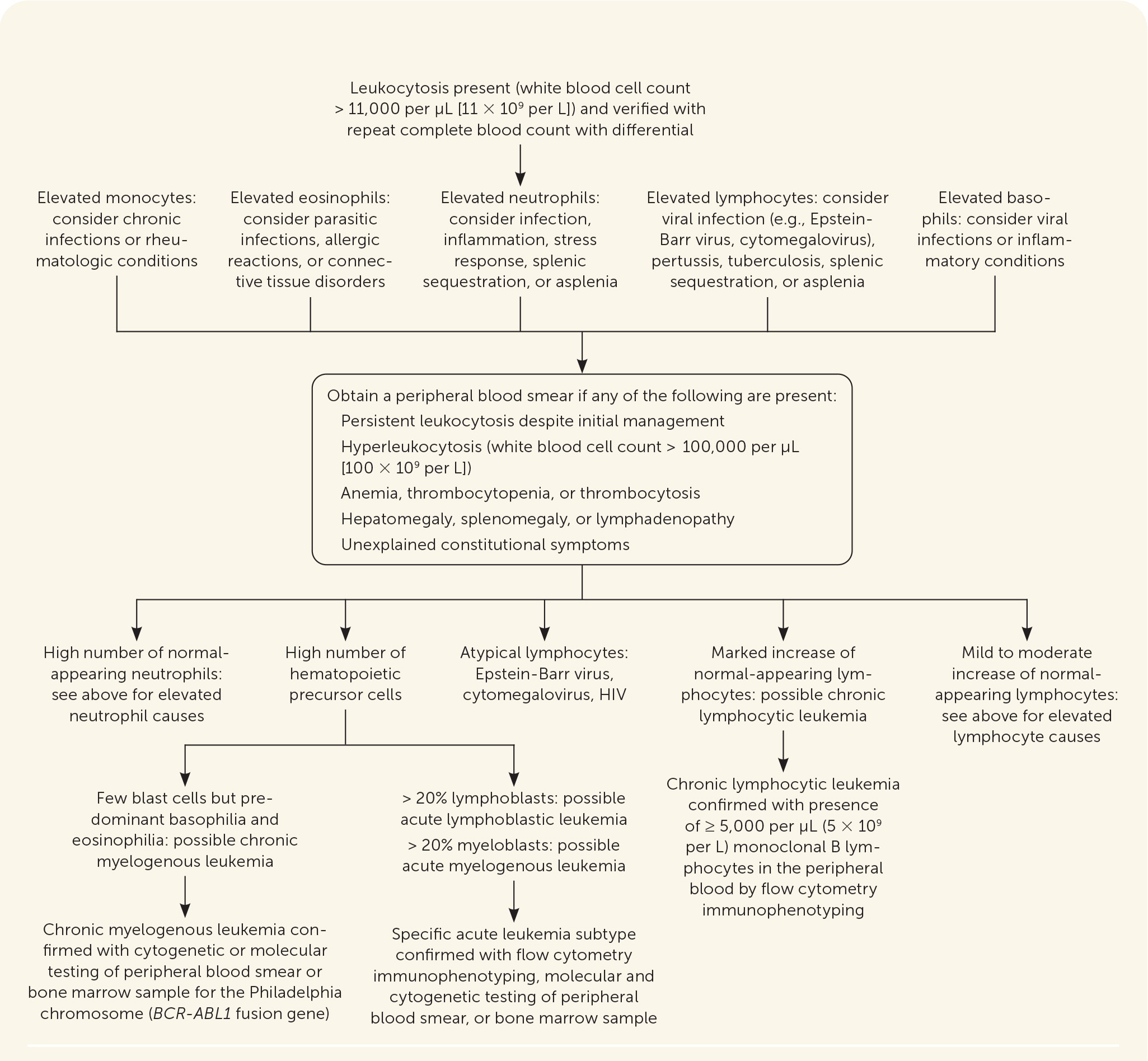

Further diagnostic testing involves peripheral blood smear evaluation and bone marrow aspiration with or without core biopsy. Cerebrospinal fluid collection is recommended for all patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia and for patients with acute myelogenous leukemia who receive intrathecal therapy.20 Figure 1 outlines the initial steps in the evaluation of possible leukemia.15

ACUTE LEUKEMIA

Acute leukemia should be suspected when blast cells are seen on a peripheral blood smear or bone marrow sample. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is diagnosed when more than 20% of cells in a bone marrow sample are lymphoblasts.3,16,22 Acute myelogenous leukemia is diagnosed when more than 20% of the cells in a peripheral blood smear or bone marrow biopsy are myeloblasts.2,17,22 Auer rods on a peripheral blood smear support the diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia.17 The absence of blast cells on a peripheral blood smear does not rule out the diagnosis of acute leukemia. Further diagnostic testing with bone marrow biopsy, flow cytometry immunophenotyping, or molecular and cytogenetic testing help distinguish between acute leukemia subtypes.20,22 Table 2 summarizes common diagnostic tests for the evaluation of leukemia.15

| Test | Description | Clinical applications |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral blood smear | Examination of whole blood specimen under the microscope | Identification of Auer rods in acute myelogenous leukemia, smudge cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and blast cells in acute myelogenous and acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Bone marrow aspirate or biopsy | Examination of hematopoietic cell lines | Identification of blast cells in acute leukemia Extent of marrow involvement correlates with prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| Cytogenetic testing | Chromosome examination through karyotyping or fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis | Detection of Philadelphia chromosome (BCR-ABL1 fusion gene) for the diagnosis of chronic myelogenous leukemia Identifying chromosomal abnormalities to diagnose leukemia subtypes Increased use of fluorescence in situ hybridization testing to guide treatment and determine prognosis, especially in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| Flow cytometry with immunophenotyping | Sorting and counting cells from peripheral blood or bone marrow sample by specific cell surface markers | Counting cloned cells of lymphoid lineage for the diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia Identifying certain cell surface markers to diagnose leukemia subtypes |

| Molecular testing with next generation sequencing | Testing for DNA mutations through polymerase chain reaction testing | Detection of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene for diagnosis of chronic myelogenous leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome–like acute lymphoblastic leukemia Aids in the diagnosis of leukemia subtypes; guides targeted treatment and risk stratification and determines prognosis |

CHRONIC LEUKEMIA

Hyperleukocytosis (more than 100,000 per μL [100 × 109 per L] white blood cells) is a hallmark of chronic myelogenous and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.4,14 A peripheral blood smear should be obtained if hyperleukocytosis is present on complete blood count, especially when associated with anemia, thrombocytopenia, thrombocytosis, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, or unexplained constitutional symptoms. The diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia requires at least 5,000 per μL (5 × 109 per L) monoclonal B lymphocytes on a peripheral blood smear and should be confirmed with flow cytometry.4 Bone marrow biopsy may be performed for treatment and prognostic purposes but is not required for the diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.19 Chronic myelogenous leukemia is characterized by identification of the Philadelphia chromosome through cytogenic or molecular testing of bone marrow or peripheral blood smear.14 The Philadelphia chromosome results from reciprocal translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22 and leads to the formation of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene.14,18 The Philadelphia chromosome is found in 90% to 95% of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia and in about 2% to 4% of children and 20% to 40% of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3,14

Treatment

Referral to a hematologist-oncologist for diagnosis confirmation and treatment is strongly recommended when leukemia is suspected. Acute leukemia treatment may include chemotherapy, radiation, targeted molecular therapy, monoclonal antibodies, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Treatment depends on patient age, comorbidities, leukemia subtype, and cytogenetic and molecular findings. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is usually reserved for patients who are younger, who have advanced disease, or whose symptoms do not respond to targeted therapies.2–4,14

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children has a 90% cure rate with standard chemotherapy regimens; the cure rate in adults is 40% to 50%.3 The survival rate in adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia has improved with the recent incorporation of targeted cancer therapies.3 Targeted cancer therapies, such as small-molecule inhibitors that target protein kinases exploited by cancer cells, monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and immunotherapy, are chemotherapeutic agents that target cancer-related mutations, genetic events, and surface proteins.23,24 Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an immunotherapy agent for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in patients 25 years and younger.2

Asymptomatic, early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (i.e., absence of anemia and thrombocytopenia and less than three areas of lymph node involvement) may be monitored without treatment.4,19 Progression to active-stage disease is defined by worsening constitutional symptoms, lymphocytosis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, progressive lymphadenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly and requires treatment.4

Patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with imatinib (Gleevec), a BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, have shown consistent long-term improvement with minimal adverse effects.25 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors combined with standard chemotherapy are used to treat Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 Other small-molecule inhibitors, including venetoclax (Venclexta), are used in the treatment of acute myelogenous and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4,17,19

TREATMENT COMPLICATIONS

Tumor lysis syndrome is caused by the release of intracellular metabolites into the bloodstream and can occur spontaneously or after the initiation of cytotoxic treatments. It occurs more frequently in acute leukemia and may cause uremia, hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and possible renal failure.21,26 Aggressive intravenous fluid hydration and administration of allopurinol or rasburicase (Elitek), a recombinant urate oxidase, are the mainstays of treatment.21,26

Immunosuppression secondary to chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation, or leukemia increases the risk of serious infections. Neutropenic fever (i.e., less than 500 neutrophils per μL [0.5 × 109 per L]) should prompt immediate evaluation for an infectious cause. Treatment should include empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.27 Empiric antifungal therapy may be initiated in patients who have persistent fever or are clinically unstable.27

Serious adverse effects of targeted cancer therapies include cardiovascular disease, arrhythmias, QT prolongation, pleural effusions, and hepatotoxicity.16–19,24 Imatinib should not be used during pregnancy due to the risk of fetal abnormalities.18 Because of the potential for possible interactions between small-molecule inhibitors and medications commonly prescribed by primary care physicians (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, macrolide antibiotics), a detailed medication review for drug-drug interactions is recommended.24

Graft-versus-host disease presents as a maculopapular rash, diarrhea, and abdominal pain and may occur with stem cell transplantation.28 Prophylactic techniques, such as irradiation of blood products or pretransplant chemotherapy and radiation, have reduced the incidence of this complication.2,19,28

Prognosis and Long-term Sequelae

Prognostic factors include patient age, comorbidities, leukemia subtype, clinical presentation at the time of diagnosis, and cytogenetic and molecular findings.1–4,11–14,29 Patients with minimal residual disease, which occurs when a small number of cancer cells are detected through flow cytometry despite clinical remission after treatment, have a poor prognosis.3

Leukemia survivors have an increased risk of developing secondary cancers, endocrine and musculoskeletal disorders, and cardiovascular disease.30 Reductions in chemoradiation doses for childhood leukemia have decreased the incidence of secondary cancers from 2.9% in the 1970s to 1.5% in the 1990s.31 The most common nonmalignant tumors in childhood leukemia survivors are meningioma and basal cell carcinoma, whereas the most common malignant tumors are breast and thyroid.30,31 In adults, up to 23% of patients with past or current chronic lymphocytic leukemia may develop an aggressive lymphoma two to six years after diagnosis.4

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that childhood leukemia survivors who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (e.g., daunorubicin, doxorubicin) have echocardiography performed six to 12 months after completing treatment.30 Osteonecrosis of the hips, knees, or shoulders may develop up to 13 years after treatment in childhood leukemia survivors.30 The risk of infertility, metabolic syndrome, hypogonadism, and hypothyroidism is also increased in leukemia survivors.30 Guidelines recommend fertility counseling and preservation discussions before treatment initiation, periodic screening for endocrinopathies and psychosocial outcomes, and routine age- and sex-specific preventive health screenings and counseling.16–19,24,27,30,32,33 Monitoring and surveillance guidelines are summarized in Table 3.15

| Leukemia subtype | Examinations | Laboratory testing | Vaccinations | Cancer screenings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Annual physical examination, including growth assessment, skin examination, and testicular examination Annual eye and dental examinations Chest radiography, pulmonary function testing, and audiometry as needed based on symptoms Baseline ECG every two to five years if treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (e.g., daunorubicin, doxorubicin) Patients treated with HSCT: One year post-HSCT: bone density testing, eye examination, pulmonary function test After one year: annual physical examination, including growth assessment and full body skin examination; annual audiology; eye and dental examinations Patients with cranial or craniospinal radiation: Low threshold for neuroimaging for neurologic symptoms | Patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Annual CBC with differential up to 10 years after last treatment Annual comprehensive metabolic panel, liver and thyroid function testing, magnesium and phosphorous levels Urinalysis if presenting with hematuria, frequency, or urgency If treated before 1972, one-time hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody and hepatitis C antibody testing If treated before 1993, one-time hepatitis C antibody testing If treated between 1977 and 1985, one-time HIV testing Patients treated with HSCT: CBC every one to two months for the first year, every three to six months for the second year, and every six to 12 months after two years One year post-HSCT: Comprehensive metabolic panel (including magnesium, calcium, and phosphorous levels), urinalysis, liver function tests, ferritin level After one year: annual comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, magnesium and phosphorous levels | Age-appropriate immunizations Live vaccines should not be administered during chemotherapy Live vaccines may be administered 24 months post-HSCT Inactivated vaccines may be administered six to 12 months post-HSCT | Age- and sex-specific cancer screening |

| Acute myelogenous leukemia | Patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Annual physical examination Baseline ECG every two to five years if treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (e.g., daunorubicin, doxorubicin) Patients treated with HSCT: One year post-HSCT: bone density testing, eye examination, pulmonary function test After one year: annual physical examination, including growth assessment and full body skin examination; annual audiology; eye and dental examinations | Patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: CBC every one to two months for two years, then every three to six months for up to five years Patients treated with HSCT: CBC every one to two months for the first year, every three to six months for the second year, and every six to 12 months thereafter One year post-HSCT: Comprehensive metabolic panel (including magnesium, calcium, and phosphorous levels), urinalysis, liver function tests, ferritin level After one year: annual comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, magnesium and phosphorous levels | Age-appropriate immunizations Live vaccines should not be administered during chemotherapy Live vaccines may be administered 24 months post-HSCT Inactivated vaccines may be administered six to 12 months post-HSCT | Age- and sex-specific cancer screening |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Patients being monitored without treatment: History and physical examination every six to 12 months assessing for progressive symptoms (e.g., fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, fever); examination should include evaluation for hepatosplenomegaly and skin examination to assess for skin cancer Patients receiving treatment: Baseline ECG with referral to cardiologist depending on findings or if signs or symptoms of heart failure develop | CBC every six to 12 months; if progressive anemia or thrombocytopenia develop, refer to hematologist | Avoid live vaccination for patients being monitored without treatment COVID-19 vaccination Pneumococcal vaccination every five years Annual influenza vaccine | Age and sex-specific cancer screening |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | Patients being treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor: Annual physical examination with monitoring for adverse effects, including arteriothrombotic events, cardiovascular complications, diarrhea, edema, gastrointestinal upset, headache, and muscle cramps | Patients being treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor: CBC every three months; if leukopenia or thrombocytopenia develop, refer to hematologist | Age-specific immunizations | Age- and sex-specific cancer screenings |

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Davis, et al.15

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key words leukemia, acute leukemia, and chronic leukemia. An Essential Evidence Plus search was completed using the key words leukemia, acute leukemia, and acute lymphocytic leukemia. We accessed the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results Program online database of cancer statistics and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network database. Search dates: May through July 2022, and February 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.