Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(4):383-395

Patient information: See related handout on lupus.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that affects the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hematologic, integumentary, musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, pulmonary, renal, and reproductive systems. It is a chronic disease and may cause recurrent flare-ups without adequate treatment. The newest clinical criteria proposed by the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology in 2019 include an obligatory entry criterion of a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1: 80 or greater. Management of SLE is directed at complete remission or low disease activity, minimizing the use of glucocorticoids, preventing flare-ups, and improving quality of life. Hydroxychloroquine is recommended for all patients with SLE to prevent flare-ups, organ damage, and thrombosis and increase long-term survival. Pregnant patients with SLE have an increased risk of spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Preconception counseling regarding risks, planning the timing of pregnancy, and a multidisciplinary approach play a major role in the management of SLE in patients contemplating pregnancy. All patients with SLE should receive ongoing education, counseling, and support. Those with mild SLE can be monitored by a primary care physician in conjunction with rheumatology. Patients with increased disease activity, complications, or adverse effects from treatment should be managed by a rheumatologist.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that affects multiple organ systems. Its course is typically recurrent, with periods of relative remission followed by flare-ups. SLE can affect anyone, but it is more common in women between 15 and 44 years of age. The incidence and prevalence of SLE in North America are 23.2 per 100,000 person-years and 241 per 100,000 people, respectively.1

| The newest clinical criteria proposed by the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology in 2019 include an obligatory entry criterion: a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1: 80 or greater. |

| Patients with chronic kidney disease should receive one dose of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20 or PCV15). When PCV15 is used, it should be followed by a dose of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). |

| Anifrolumab (Saphnelo) and voclosporin (Lupkynis) are new medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. |

Classification Criteria

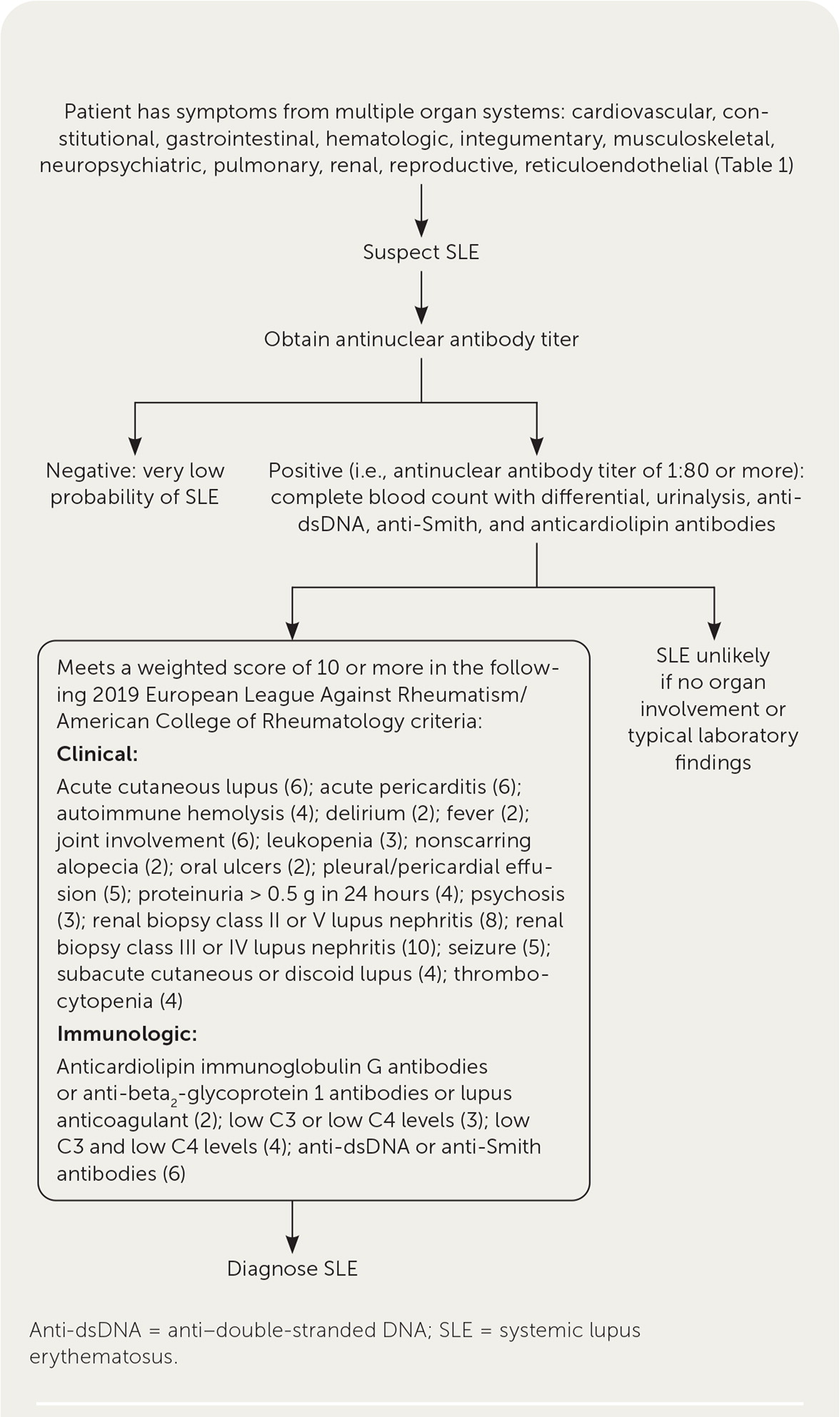

Clinicians should have high suspicion for SLE in patients with symptoms involving multiple organ systems. Three classification approaches have evolved and provide some perspective on features of the disease, but these are not diagnostic criteria. These classification criteria are designed to standardize patients for entry into clinical trials. However, these criteria are often used clinically to evaluate patients.

Based on the 1997 update of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, patients meet criteria for SLE if they have four or more of the 11 symptoms.2,3 However, it was noted that not all patients meeting the criteria will have lupus and not all patients with clinically diagnosed lupus will meet the threshold criteria of four or more of the 11 symptoms.4,5 Because of this, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) proposed new criteria in 2012.6 According to the SLICC criteria, patients must meet at least four criteria, including at least one clinical and one immunologic criterion, or the patient should have a biopsy confirming lupus nephritis and elevated antinuclear antibody (ANA) or anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) levels without any other criteria.6 The SLICC criteria have increased sensitivity (97%) and decreased specificity (84%) compared with the ACR criteria.6

The newest clinical criteria proposed by the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology (EULAR/ACR) in 2019 include an obligatory entry criterion of a positive ANA titer of 1: 80 or greater. The EULAR/ACR criteria have a sensitivity of 96% and an increased specificity of 93%. In these criteria, points are given for each clinical and immunologic criterion met. If the ANA titer is positive, the criteria are additively weighted from 2 to 10, with a score of 10 required for classification. These weighted criteria are clinical (e.g., constitutional, hematologic, neuropsychiatric, muco-cutaneous, serosal, musculoskeletal, renal) and immunologic (i.e., antiphospholipid antibodies, complement proteins, and SLE-specific antibodies).7 A diagnosis of SLE is made in consultation with a rheumatologist. Table 1 summarizes the classification criteria of SLE.3,7,8

| System | ACR criteria (1997)* | SLICC criteria (2012)† | EULAR/ACR (2019)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular/pulmonary | Pleuritis (pleuritic pain or rub or pleural effusion) or pericarditis (documented by electrocardiography, rub, or pericardial effusion) | Serositis (pleurisy for more than one day, pleural effusion, or pleural rub; pericardial pain for more than one day, pericardial effusion, pericardial rub, or pericarditis) | Pleural or pericardial effusion (5); acute pericarditis (6) |

| Constitutional | — | — | Fever > 100.9°F (38.3°C) (2) |

| Hematologic | Hemolytic anemia, leukopenia (< 4,000 cells per mm3), lymphopenia (< 1,500 cells per mm3), or thrombocytopenia (< 100,000 cells per mm3) | Hemolytic anemia; leukopenia (< 4,000 cells per mm3) more than once or lymphopenia (< 1,000 cells per mm3) more than once; thrombocytopenia (< 100,000 cells per mm3) | Leukopenia (3); thrombocytopenia (4); autoimmune hemolysis (4) |

| Immunologic | Positive test result for antinuclear antibodies; elevated anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, or antiphospholipid antibodies; discoid rash; photosensitivity; oral or nasal ulcers | Positive test result for antinuclear antibodies; elevated anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, or antiphospholipid antibodies; low complement (C3, C4, or CH 50) or direct Coombs test (in the absence of hemolytic anemia); chronic cutaneous lupus, nonscarring alopecia, or oral or nasal ulcers | Anticardiolipin immunoglobulin G or anti-beta2-glycoprotein 1 antibodies or lupus anticoagulant (2); low C3 or C4 (3); low C3 and low C4 (4); anti-dsDNA or anti-Smith antibodies (6) |

| Integumentary/mucosal | Malar rash | Acute cutaneous lupus or subacute cutaneous lupus | Nonscarring alopecia (2); oral ulcers (2); subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus (4); acute cutaneous lupus (6) |

| Musculoskeletal | Nonerosive arthritis involving two or more joints | Synovitis involving two or more joints or tenderness at two or more joints and at least 30 minutes of stiffness in the morning | Joint involvement (6) |

| Neuropsychiatric | Seizure or psychosis | Seizure, psychosis, mononeuritis complex, myelitis, or peripheral or cranial neuropathy | Delirium (2); psychosis (3); seizure (5) |

| Renal | Persistent proteinuria (> 0.5 g in 24 hours or > 3+ on urine dipstick testing) or cellular casts | Urinary creatinine (or 24-hour urinary protein) > 500 mg or red blood cell casts | Proteinuria > 0.5 g in 24 hours (4); renal biopsy class II or V lupus nephritis (8); renal biopsy class III or IV lupus nephritis (10) |

Diagnosis

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

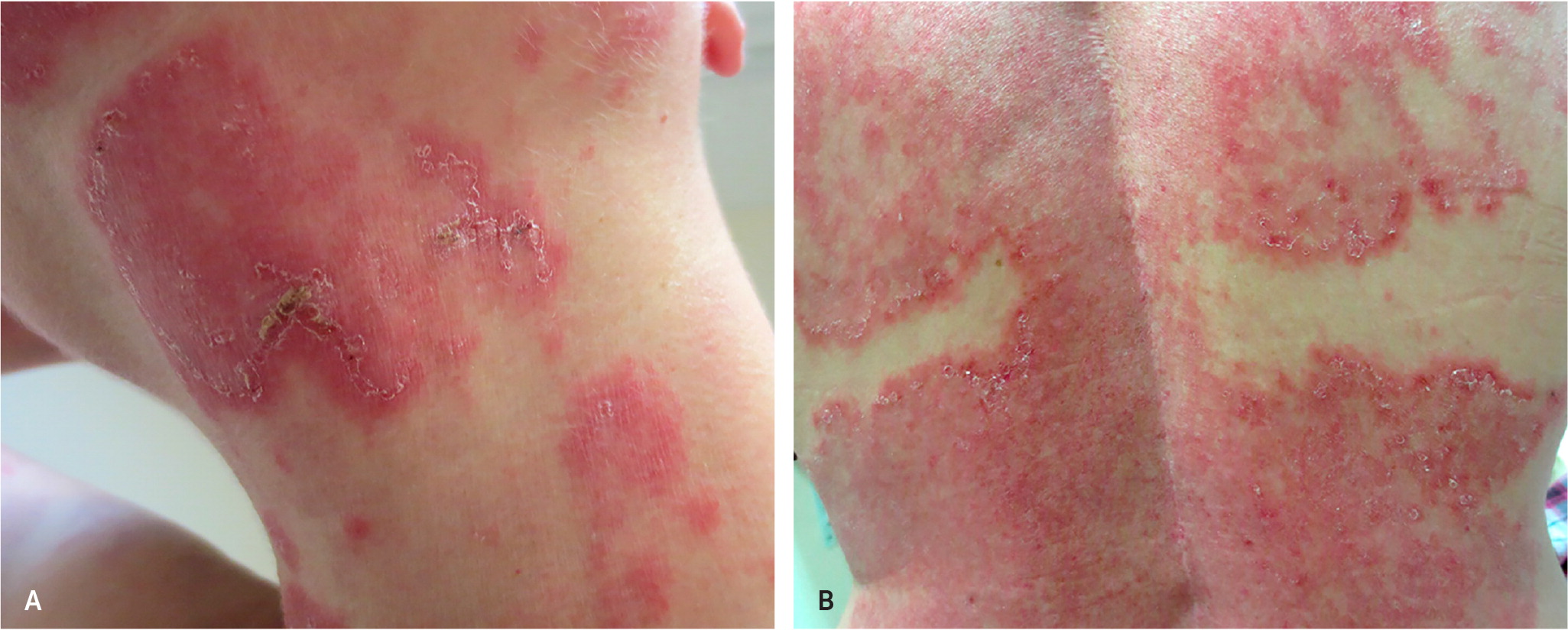

Patients with SLE commonly present to their family physicians with multiple nonspecific symptoms, making it difficult to diagnose. Laboratory testing may be negative early in the onset of SLE. Fatigue is the most prevalent symptom and is nonspecific but may be associated with weight loss, fever without a source of infection, and joint pain.10 Malar rash (31%; Figure 2), photosensitivity with associated acute and subacute cutaneous lupus rash (23%; Figure 39), pleuritic chest pain (16%), Raynaud phenomenon (16%), and mouth sores (12.5%) are less common.11 The differential diagnosis for SLE is summarized in Table 2.12

| Differential diagnosis | Distinguishing features | Diagnostic approach |

|---|---|---|

| Adult-onset Still disease | Arthralgia, fever, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly | Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated ferritin level, leukocytosis, and anemia |

| Behçet syndrome | Aphthous ulcers, arthralgia, uveitis | Recurrent oral ulcers plus two of the following: eye lesions, genital ulcers, skin lesions |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | Persistent and unexplained fatigue that significantly impairs daily activities | Perform the following tests to rule out other diseases: complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level, complete metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, urinalysis |

| Endocarditis | Arterial emboli, arthralgia, fever, heart murmur, myalgia | Positive echocardiography findings with vegetation on heart valve; positive blood culture |

| Fibromyalgia | Poorly localized musculoskeletal pain with hyperalgesia and allodynia | Digital palpation of soft tissue tender points: gluteal, greater trochanter, knee, lateral epicondyle, low cervical, occiput, second rib, supraspinatus, trapezius |

| HIV infection | Arthralgia, fever, lymphadenopathy, malaise, myalgia, peripheral neuropathy, rash | Western blot assay for detection of HIV antibodies |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Diarrhea, peripheral arthritis, rectal bleeding, tenesmus | Perform colonoscopy to assess disease activity; measure C-reactive protein level, platelets, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate; test for anemia |

| Lyme disease | Arthritis, carditis, erythema migrans, neuritis | Perform serologic testing for Lyme disease |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | Arthralgia, myalgia, puffy fingers, Raynaud phenomenon, sclerodactyly | Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and hypergammaglobulinemia; positive anti-U1RNP antibodies |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Psoriasis before or after joint disease, nail changes in fingers and toes | Inflammatory articular disease and more than three of the following: dactylitis, nail changes, negative rheumatoid factor, psoriasis, radiographic evidence of new bone formation in hand or foot |

| Reactive arthritis | Acute nonpurulent arthritis from infection elsewhere in the body; evaluate for infectious urethritis or colitis | Clinical diagnosis to identify triggers; serologic findings of recent infections may be present |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Morning joint stiffness lasting more than one hour; affected joints are usually symmetrical, tender, and swollen | Positive test results for rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated antibodies; synovial fluid reflects inflammatory state |

| Sarcoidosis | Cough, dyspnea, fatigue, fever, night sweats, rash, uveitis | Perform chest radiography; bilateral adenopathy with biopsy revealing noncaseating granuloma; elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme level |

| Systemic sclerosis | Arthralgia, decreased joint mobility, myalgia, Raynaud phenomenon, skin induration | Perform tests for specific autoantibodies |

| Thyroid disease | Dry skin, fatigue, feeling cold, weakness | Measure thyroid-stimulating hormone |

INITIAL EVALUATION

SLE should be considered in patients who present with symptoms involving multiple organ systems after ruling out infectious causes. In addition to constitutional symptoms, the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hematologic, integumentary, musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, pulmonary, renal, and reproductive systems are most often affected.8 The reticuloendothelial system involving the phagocytic function of macrophages and monocytes also may be affected.

When SLE is clinically suspected, the diagnostic workup should collect information that allows appropriate use of new classification criteria. The EULAR/ACR classification system helps classify SLE based on a combination of physical findings and laboratory criteria. The clinician should obtain an initial ANA titer. ANA is not specific but highly sensitive in about 95% of patients.13 SLE is uncommon in patients with a negative ANA titer. A positive ANA titer may occur in conditions such as systemic sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, viral infections, and autoimmune thyroid disease.14,15

In patients with a positive ANA titer, specific laboratory tests should include anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anticardiolipin, anti-beta2-glycoprotein 1, and lupus anticoagulants, all of which can be applied to the classification system.12 Urinalysis, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and a direct Coombs test should be obtained with the initial evaluation. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are useful in quantifying the disease activity.16

Depending on the results of the initial evaluation, further testing may include skin, kidney, muscle, or nerve biopsy. A kidney biopsy is recommended by the ACR for patients with evidence of active lupus nephritis, helping to classify the disease.17 Use of magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, ultrasonography, or other testing may be indicated. These results help identify existing conditions that may lead to disease flare-ups and complications and influence the treatment plan. For example, individuals with a history of seizures would require magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and electroencephalography for further workup, or patients with cognitive impairment would have a neuropsychological evaluation by a psychologist to establish a baseline.18

Assessment of Severity

A disease flare-up consists of a measurable increase in disease activity, usually leading to a change in treatment.19 Some circumstances that increase disease flare-ups include sunlight exposure, hormonal changes, infection, and medications.

There are multiple tools to assess disease severity, but the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) is the most commonly used. The tool is available online at https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10099/systemic-lupus-erythematosus-disease-activity-index-2000-sledai-2k.

Management

GOALS OF TREATMENT

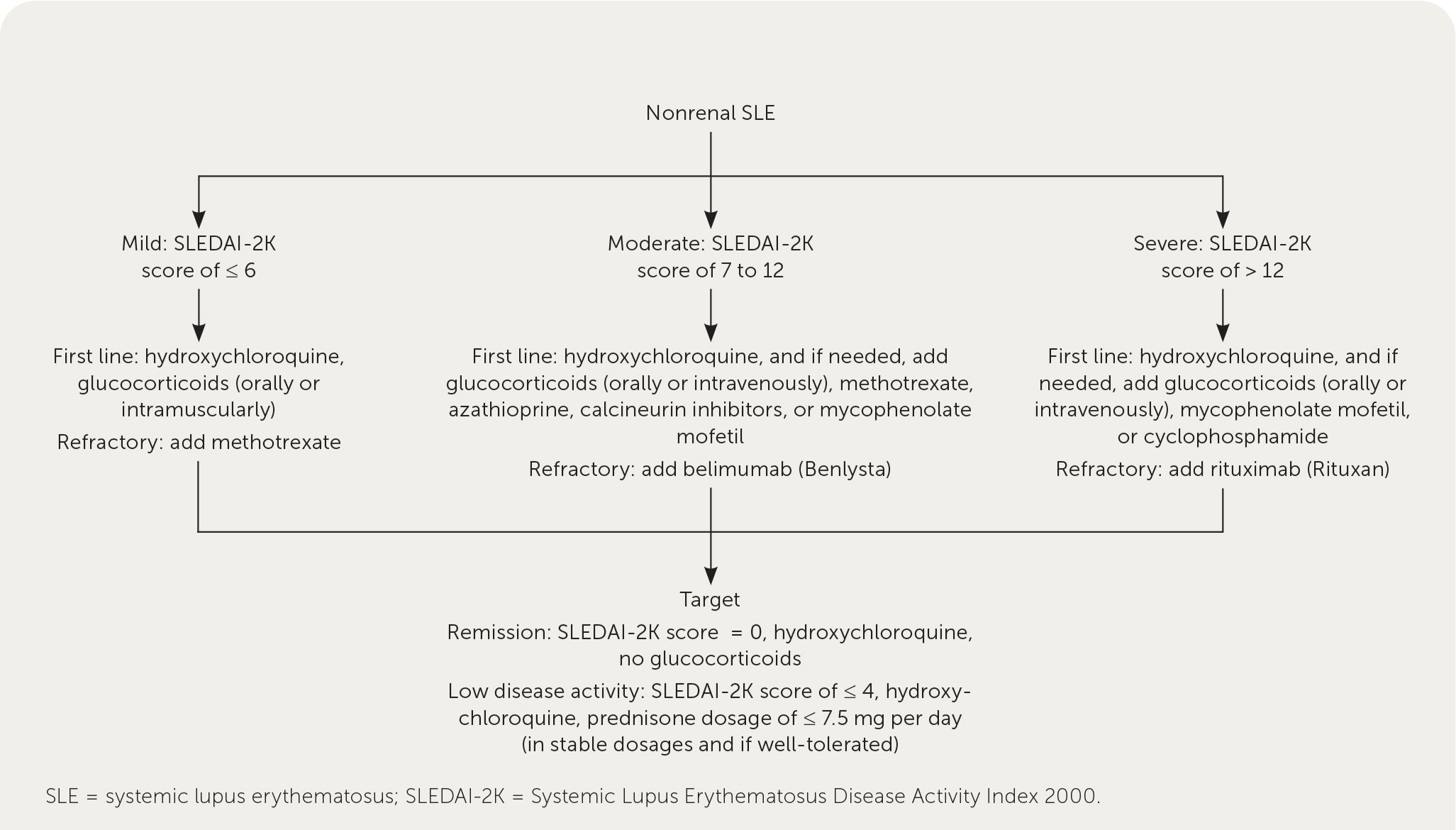

Management of SLE is directed at achieving complete remission or low disease activity, minimizing the use of glucocorticoids, preventing flare-ups, and improving quality of life.19,22,23 Complete remission is defined as the absence of clinical activity (i.e., a SLEDAI-2K score of 0) with no use of glucocorticoid or immunosuppressive therapy.24 Low disease activity is a SLEDAI-2K score of 3 or less while on anti-malarials (e.g., hydroxychloroquine), or a SLEDAI-2K score of 4 or less while taking no more than 7.5 mg per day of prednisone and well-tolerated immunosuppressive agents. 25 Therapies are typically managed by or co-managed with experts in rheumatology. Management in severe disease may require a multidisciplinary approach.19 Table 3 lists medications used to treat SLE.8,17,26–28

| Medication | Indication | Dosage | Monitoring and precautions | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line treatment | ||||

| Glucocorticoids | Low dose for treating SLE without major organ damage; high dose for cerebritis, lupus nephritis, refractory conditions, and thrombocytopenia | Low dose: ≤ 7.5 mg of prednisone per day High dose: 40 to 60 mg of prednisone per day | Glucose levels every three to six months and total cholesterol and bone density testing annually; use with caution in patients with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, infection, or osteoporosis | $5 (—) for 30 10-mg prednisone tablets; $7 (—) for 60 20-mg prednisone tablets |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Recommended for all patients with SLE; long-term protective effect on SLE-related organ damage | 5 mg per kg of body weight per day (200 to 400 mg per day) | Baseline funduscopic examination, visual field testing, and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography should be performed at the time of initiation; annual screening is performed in those at high risk but can be deferred to every five years in low-risk patients at the time of initiation, then annually | $6 (—) for 30 200-mg tablets |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Lupus joint pain | Depends on preparation | Complete blood count and renal testing annually; use with caution in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, liver or kidney disease, or hypertension | Depends on preparation |

| Second-line treatment | ||||

| Azathioprine | Lupus nephritis, severe SLE | 1.5 to 2.5 mg per kg per day | Complete blood count and metabolic panel at least every three months to monitor for hepatotoxicity, lymphoproliferative disorders, and myelosuppression | $15 (—) for 60 50-mg tablets |

| Methotrexate | Arthritis, cutaneous lupus, serositis, severe SLE | 7.5 to 25 mg per week | Complete blood count and metabolic panel at least every three months to monitor for hepatic fibrosis or myelosuppression; additional monitoring for fibrosis and pulmonary infiltrates | $3 (—) for 12 2.5-mg tablets |

| Third-line treatment | ||||

| Anifrolumab (Saphnelo) | Moderate and severe SLE, lupus nephritis | 300 mg every four weeks administered via intravenous infusion | Monitor for respiratory tract infections and hypersensitivity | Only administered by a health care professional |

| Belimumab (Benlysta) | SLE | 10 mg per kg per intravenous dose 200 mg subcutaneously once per week | Monitor for serious infection and malignancies | Only available at specialty pharmacies |

| Cyclophosphamide | Lupus nephritis, severe SLE | 500 to 1,000 mg per m2 intravenously once per month | Complete blood count and metabolic panel at least every three months to monitor for hemorrhagic cystitis, immunosuppression, malignancy, and myelosuppression | Only administered by a health care professional |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Lupus nephritis, refractory SLE | 2 to 3 g per day | Complete blood count and metabolic panel at least every three months to monitor for infection and myelosuppression | $30 (—) for 240 250-mg capsules |

| Rituximab (Rituxan) | Refractory severe SLE | One-time administration of two 1-g doses intravenously, two weeks apart | Complete blood count every two to four months; use with caution in patients with a history of infusion reaction | Only available at specialty pharmacies |

| Voclosporin (Lupkynis) | Lupus nephritis | 23.7 mg orally every 12 hours | Establish baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate prior to initiating, then every two weeks for the first month and every four weeks thereafter; monitor blood pressure every two weeks | Only available at specialty pharmacies |

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine is recommended for all patients with SLE because it prevents flare-ups, organ damage, and thrombosis and increases long-term survival.19,29 It has a long half-life and may take two to eight weeks to be effective. Retinal toxicity is the main adverse effect. Based on existing evidence that shows the risk of toxicity is very low for doses below 5 mg per kg of body weight, the daily dosage should not exceed this threshold.19 Risk factors for retinal toxicity include longer duration of use, higher dosage, preexisting retinal or macular disease, older age, concomitant use of tamoxifen, and kidney and liver disease.19,30 Baseline funduscopic examination, visual field testing, and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography should be performed to rule out preexisting maculopathy at the time of initiation. Annual screening should be performed in those at high risk but can be deferred to five years in low-risk patients.29,31

Glucocorticoids. Glucocorticoids provide rapid symptom relief in acute disease and during flare-ups. Prolonged glucocorticoid use can have detrimental effects, including irreversible organ damage. The aim should be to minimize the daily dosage of prednisone to 7.5 mg or less or discontinue glucocorticoids.32 Early initiation of immunosuppressive agents helps patients to taper and eventually discontinue glucocorticoids. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (usually 250 to 1,000 mg per day for three days) may be used in acute, organ-threatening disease or during severe flare-ups.33

Immunosuppressive Therapy. The choice of agent depends on disease manifestations, patient age, childbearing potential, safety concerns, and cost.19 Methotrexate and azathioprine may be considered if a trial of hydroxychloroquine fails to manage the disease or glucocorticoids cannot be tapered off. Mycophenolate mofetil is a potent immunosuppressant with effectiveness in renal and nonrenal lupus.34,35 Cyclophosphamide may be used in organ-threatening disease, especially affecting the renal, cardiopulmonary, or neuropsychiatric systems.

Biologic Agents. Belimumab (Benlysta), a B lymphocyte stimulating factor, is used in SLE and lupus nephritis when first-line treatments provide inadequate control. Patients more likely to respond are those with high disease activity, who are taking a prednisone dosage of more than 7.5 mg per day, and with serologic activity (low C3/C4, high anti-dsDNA antibody titers).36,37

Several open-label trials and registry studies have found that rituximab (Rituxan) is effective in SLE that is resistant to standard treatment. Because of insufficient evidence from randomized controlled trials, rituximab is currently used off-label in patients with severe renal, hematologic, and neuropsychiatric disease; in patients with SLE that has been resistant to other immunosuppressive agents and/or belimumab; or in patients for whom other therapeutic options are contraindicated. More than one immunosuppressive drug needs to have been ineffective before administering rituximab.38,39

Voclosporin (Lupkynis) is an oral calcineurin inhibitor immunosuppressant approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for the treatment of lupus nephritis in combination with mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticoids. 27 Anifrolumab (Saphnelo) is an immunoglobulin gamma 1 kappa monoclonal antibody antagonist of the type 1 interferon receptor and was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for the treatment of moderate and severe SLE.28

SPECIFIC ORGAN SYSTEM COMPLICATIONS

Screening for nephritis with urinalysis and serum creatinine levels should be done at three- to six-month intervals in all patients with SLE. For patients with features suggesting nephritis, a 24-hour urine test for protein or a spot urine protein/creatinine ratio should be obtained.17 Referral for renal biopsy should be considered in patients with proteinuria of at least 1 g in 24 hours or at least 0.5 g in 24 hours with hematuria or cellular casts. Mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide are the immunosuppressive agents of choice for induction therapy for lupus nephritis. Mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine may be used for maintenance therapy. Management of specific organ systems in patients with SLE is summarized in Table 4.19,40–45 Figure 4 outlines the management of nonrenal SLE.19,46

| Organ system | Lifetime prevalence | Treatment | Prevention and screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 28% to 40% | Antihypertensive agents, cholesterol-lowering agents | Treat risk factors aggressively |

| Hematologic | Most patients | Thrombocytopenia: First line: glucocorticoids plus immunosuppressive therapy (i.e., azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclosporine); intravenous methylprednisolone with or without intravenous immunoglobulins Refractory: rituximab Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: glucocorticoids plus immunosuppressive therapy | Monitor and treat infection, especially in patients with leukopenia |

| Integumentary | 70% to 80% | First line: topical agents (e.g., glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors) and hydroxychloroquine with or without systemic glucocorticoids. Refractory: methotrexate; other agents include retinoids, dapsone (Aczone), and mycophenolate mofetil | Use sunscreen and wear protective clothing |

| Musculoskeletal | 95% | First line: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine, glucocorticoids Refractory: immunosuppressive therapy such as methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil | — |

| Neuropsychiatric | 12% to 23% | Based on etiology: Inflammatory: glucocorticoids with or without immunosuppressive therapy Embolic/thrombotic/ischemic: anticoagulant | Control aggravating factors and symptoms |

| Pulmonary | 16% | Depends on type of involvement and severity; glucocorticoids, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or mycophenolate mofetil; plasmapheresis | — |

| Renal | 50% | Induction: mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide Maintenance: mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine | Urinalysis and serum creatinine test every one to three months |

PREGNANCY COMPLICATIONS

Active disease six months before pregnancy, lupus nephritis, and discontinuation of antimalarial agents are risk factors for adverse maternal outcomes.29 Preconception counseling regarding risks, planning the timing of pregnancy, and using a multidisciplinary approach play a major role in the management of SLE in patients contemplating pregnancy.

Hydroxychloroquine should be continued during pregnancy because it has been shown to control disease activity. It may reduce pregnancy complications, including preeclampsia and cardiac neonatal lupus.47–50 Prednisone, azathioprine, and tacrolimus may be used in pregnancy if benefits outweigh risks, whereas methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, and leflunomide are contraindicated in pregnancy. Mycophenolate mofetil is highly teratogenic and should be discontinued at least six weeks before conceiving. These patients can be switched to azathioprine and/or tacrolimus at least three months before conception to help decrease disease activity. According to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, low-dose aspirin should be initiated in pregnant patients with an increased risk of preeclampsia after 12 weeks of gestation.51

Patients should be closely monitored throughout pregnancy to detect and manage complications or flare-ups. Patients with SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome may need additional anticoagulant agents throughout pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

Other than a consultation with a physician specializing in maternal-fetal medicine and a rheumatologist, the evaluation should include an assessment of antiphospholipid antibodies and anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B antibodies. Anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies may be present in patients with SLE and can be cardiotoxic to the fetus. Varying degrees of congenital heart block can be seen in 1% to 3% of children born to patients who are seropositive.52 Heart block can be incomplete or complete, leading to heart failure in utero and hydrops fetalis. For patients with anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, fetal echocardiography should be performed multiple times from 16 through 26 weeks of gestation; this period is when the fetus has the highest risk for onset of congenital heart block.29 There is no known effective therapy for complete heart block, but incomplete heart block is often treated with dexamethasone because it can cross the placenta. Hydroxychloroquine use during pregnancy is associated with a reduced risk of fetal development of cardiac neonatal lupus.49

CONTRACEPTION

Patients with SLE can use most contraceptive methods, preferably long-acting reversible contraception such as intrauterine devices. Those with antiphospholipid syndrome should not use estrogen-containing contraceptives because of increased risk of thrombosis.53

Monitoring

SLE has wide-ranging effects on physical, psychological, and social well-being that impact quality of life. All patients with SLE should receive ongoing education, counseling, and support. Those with mild SLE can be monitored by primary care physicians in conjunction with rheumatology.8 Patients with increased disease activity, complications, or adverse effects from treatment should be managed by a rheumatologist.8 Family physicians can assist the rheumatologist in monitoring disease activity and providing pharmacotherapy in patients with moderate to severe SLE. Those with active disease should be evaluated at least every one to three months, and measurements of blood pressure, anti-dsDNA antibodies, complement and C-reactive protein levels; urinalysis; complete blood count; and kidney and liver function tests should be performed. Patients with stable low disease activity or who are in remission can be evaluated less often.46

Patients with chronic kidney disease should receive one dose of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20 or PCV15). When PCV15 is used, it should be followed by a dose of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).54 Live vaccines should not be given to patients with SLE when they are receiving immunosuppressive therapy and should be delayed for at least one month after completion of therapy.

Management of modifiable risk factors, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, high body mass index, and smoking, should be reviewed at baseline and at least annually. Immunosuppressive therapy may lead to toxicities. Close monitoring of medications by regular laboratory testing and clinical assessment should be performed in accordance with drug monitoring guidelines.46

| Complications | Frequency of follow-up | Prevention, monitoring, and management |

|---|---|---|

| None; mild, stable systemic lupus erythematosus | Every three to six months | History for features of systemic lupus erythematosus, physical examination, complete blood count, creatinine level, urinalysis, anti– double-stranded DNA antibodies, complement levels; keep all health maintenance screenings and vaccinations up to date |

| Moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus with complications | Frequent | Monitor as recommended by rheumatologist and lupus care specialists |

| Systems monitoring | ||

| Cardiovascular abnormalities | Every visit | Optimal lupus control with minimal glucocorticoid use; judicious use of antimalarial and other immunosuppressive agents; smoking cessation, adequate exercise, low-cholesterol diet, lipid-lowering therapy, blood pressure control, screening for diabetes mellitus |

| Hematology: severe hemolytic anemia | Weekly | Hematocrit and reticulocyte count; may require transfusion |

| Hematology: severe thrombocytopenia (< 50,000 cells per mm3) | Weekly | Platelet count weekly initially; may require transfusion |

| Infection | Every visit | Ensure that vaccinations are up to date; judicious use of immunosuppressive agents |

| Malignancy | Yearly | Ensure that routine cancer screenings are up to date; screen for high-risk cancers as indicated (e.g., hematologic, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lung, cervical) |

| Renal abnormalities | Every three months or more frequently, depending on disease state | Regular screening for proteinuria and hematuria; regular serum creatinine level; patients with chronic kidney disease should receive pneumococcal vaccination; new-onset nephritis needs more frequent monitoring |

| Medication monitoring | ||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Annual vision screening is performed in those at high risk but can be deferred to five years in low-risk patients at the time of initiation, then annually | Baseline funduscopic examination, visual field testing, and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography should be performed at the time of initiation |

| Low-dose glucocorticoids | Every visit to every one to two years | Keep dosage as low as possible; healthy diet with adequate physical activity; smoking cessation; annual cholesterol and glucose testing; consider dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry every one to two years for patients receiving long-term therapy |

| High-dose glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone, > 30 mg per day) | Every visit | Pursue steroid-sparing agent; use lowest dose possible to achieve optimum disease control; glucose testing every three to six months; cholesterol testing annually; dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry every one to two years; maintain high index of suspicion for avascular necrosis if patient has acute joint pain |

| Immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents | Every one to two weeks initially, then every one to three months | Complete blood count and liver function testing at baseline, then every one to two weeks at initiation of therapy, then one to three months; judicious use of immunosuppressive agents, vigilance for signs and symptoms of infection; routine cancer screening; avoidance of live vaccines; if live vaccines are needed, administer one month after completion of therapy |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Lam, et al.9; Gill, et al.58; and Petri.59

Data Sources: Dynamed, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential Evidence Plus, including POEMs, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine guidelines were searched using key words systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, SLE diagnosis, and SLICC. The American College of Rheumatology, the British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice guidelines were also searched. We used references from the previous AFP articles on this topic. Search dates: April and May 2022, and January 2023.