Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(5):525-534

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Neonatal jaundice due to hyperbilirubinemia is common, and most cases are benign. The irreversible outcome of brain damage from kernicterus is rare (1 out of 100,000 infants) in high-income countries such as the United States, and there is increasing evidence that kernicterus occurs at much higher bilirubin levels than previously thought. However, newborns who are premature or have hemolytic diseases are at higher risk of kernicterus. It is important to evaluate all newborns for risk factors for bilirubin-related neurotoxicity, and it is reasonable to obtain screening bilirubin levels in newborns with risk factors. All newborns should be examined regularly, and bilirubin levels should be measured in those who appear jaundiced. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) revised its clinical practice guideline in 2022 and reconfirmed its recommendation for universal neonatal hyperbilirubinemia screening in newborns 35 weeks' gestational age or greater. Although universal screening is commonly performed, it increases unnecessary phototherapy use without sufficient evidence that it decreases the incidence of kernicterus. The AAP also released new nomograms for initiating phototherapy based on gestational age at birth and the presence of neurotoxicity risk factors, with higher thresholds than in previous guidelines. Phototherapy decreases the need for an exchange transfusion but has the potential for short- and long-term adverse effects, including diarrhea and increased risk of seizures. Mothers of infants who develop jaundice are also more likely to stop breastfeeding, even though discontinuation is not necessary. Phototherapy should be used only for newborns who exceed thresholds recommended by the current AAP hour-specific phototherapy nomograms.

More than two-thirds of newborns develop jaundice, the clinical manifestation of hyperbilirubinemia, and most cases are physiologic and benign.1 In healthy newborns, unconjugated bilirubin, a lipid-soluble breakdown product of heme, transiently elevates during days 2 to 5 after delivery due to the turnover of fetal erythrocytes.2 The liver conjugates the bilirubin into a water-soluble form that can be excreted via urine and stool. Bilirubin levels usually return to normal over one to three weeks without intervention or adverse effects.2,3

| In 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics released new nomograms for initiating phototherapy, with higher bilirubin thresholds than previous guidelines. |

| Although previous versions of the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline included East Asian race as a risk factor for severe hyperbilirubinemia and Black race as a factor associated with decreased risk, the 2022 update removed these statements. Use of racial categories has not been associated with decreased kernicterus rates and may be associated with harms. |

Several conditions increase bilirubin beyond normal physiologic levels. Pathologic causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia include metabolic conditions (e.g., hypothyroidism), conditions that increase bilirubin production (e.g., cephalohematoma), and conditions that increase enterohepatic circulation (e.g., pyloric stenosis).2 Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is uncommon, occurring in about one in 2,500 infants.4,5 Conjugated or direct bilirubin levels of 5 mg per dL (85.5 μmol per L) or greater are likely due to cholestatic causes including biliary atresia, while lesser elevations are seen in the setting of metabolic causes, hemolysis, and infections.4,6,7

Neurotoxicity

Rarely, bilirubin crosses the blood-brain barrier and can cause serious consequences. One study performed in Canada found that acute bilirubin encephalopathy occurs in approximately 1 out of 10,000 infants.8 Symptoms include lethargy, hypotonia or hypertonia, back and neck arching, irritability, and high-pitched crying.8,9 Acute bilirubin encephalopathy fully resolves in most cases but can progress to kernicterus.4,10

Kernicterus describes the irreversible, chronic effects of bilirubin toxicity.11 It occurs in approximately 1 out of 100,000 infants in high-income countries and presents as cerebral palsy, hearing loss, gaze paralysis, dental dysplasia, and developmental disability.12–14 Because of the serious and irreversible sequelae, it is important to be aware of risk factors for neurotoxicity and routinely examine newborns for jaundice.

RISK FACTORS

Neurotoxicity risk factors are conditions that increase the ability of bilirubin to cross the blood-brain barrier (Table 1).1,2,4,10 Prematurity, hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency are the most common risk factors.13,14 Newborns who develop neurologic sequelae of hyperbilirubinemia usually have at least two neurotoxicity risk factors.15 There is no clear correlation between bilirubin level alone and the risk of developing neurotoxicity.10,16

| Gestational age < 38 weeks (risk increases with the degree of prematurity) |

| Hemolytic disease of the newborn (positive direct antiglobulin test in setting of blood group, Rh(D), or other minor red cell antigen incompatibility) |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency |

| Other hemolytic conditions: red cell enzyme deficiencies (e.g., pyruvate kinase deficiency), red cell membrane defects (e.g., hereditary spherocytosis) |

| Albumin < 3 g per dL (30 g per L) |

| Sepsis |

| Asphyxia |

| Clinical instability in the past 24 hours |

| Acidosis |

PREVENTION

HDN occurs when maternal antibodies to erythrocyte antigens cross into the fetal bloodstream and attack erythrocytes. HDN most commonly occurs in the setting of blood group or Rh(D) incompatibility and is diagnosed with a positive direct antiglobulin test result.17 Obtaining ABO blood group, Rh(D) status, and anti-erythrocyte antibody screening in all pregnant patients can identify infants at risk of HDN. The incidence of HDN has decreased substantially since the introduction of Rh0(D) immune globulin. All pregnant patients who are Rh(D) negative should receive Rh0(D) immune globulin at 28 weeks' gestation to lower the risk of HDN.4

Identifying G6PD deficiency is a challenge. A family history of G6PD is helpful if present, but many affected infants will not have a family history. Universal screening for G6PD deficiency may be cost-effective in identifying infants at higher risk of bilirubin-induced neurotoxicity.18

Diagnosing Hyperbilirubinemia

EXAMINATION

All newborns should be examined for jaundice and signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy (Table 29) at least every 12 hours from birth until hospital discharge. It is important to recognize that jaundice may not be as apparent in infants with darker skin tones. In addition to examining the skin, the physician should assess for yellowing of mucous membranes (e.g., under the tongue) and scleral icterus.19 Jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is often a sign of hemolysis.4 However, visual assessment alone should not be used to diagnose hyperbilirubinemia. Objective measurements of bilirubin should be obtained in newborns who appear to be jaundiced or have symptoms suggestive of bilirubin toxicity.4,20,21

| Stage | Signs |

|---|---|

| Early | Sleepiness or decreased alertness, poor sucking and feeding, hyperreflexia, hypotonia |

| Intermediate | Stupor, irritability, hypertonia, back and neck arching, high-pitched crying |

| Advanced | Coma, pronator spasm of upper extremities, inability to feed, apnea |

A newborn's racial or ethnic group should not be used to assess the risk of hyperbilirubinemia. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) previously included East Asian race as a risk factor for severe hyperbilirubinemia and Black race as a factor associated with decreased risk, their updated 2022 guideline on neonatal hyperbilirubinemia did not include race. The use of racial categories to assess hyperbilirubinemia risk has not been associated with decreased kernicterus rates and may be associated with harms.22

BILIRUBIN MEASUREMENT

Total serum bilirubin (TSB) and transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) are options for objective bilirubin measurement. TcB correlates with TSB at lower levels across diverse, multi-ethnic populations; however, TcB values of 15 mg per dL (256.6 μmol per L) or greater or within 3 mg per dL (51.3 μmol per L) of the phototherapy threshold should be confirmed with a TSB measurement.3,4,13,23,24 Assessing TcB decreases the need for a blood draw by more than one-third, therefore mitigating the small risks of infection and anemia associated with blood draws and avoiding the costs of serum testing.25,26

CONJUGATED AND DIRECT BILIRUBIN

Many laboratories report conjugated or direct bilirubin levels when performing a TSB measurement. A conjugated or direct (not total) bilirubin level of 5 mg per dL or greater is likely to represent cholestasis, and urgent consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist is recommended.4,6 However, a single mild elevation (less than 2 mg per dL [34.2 μmol per L]) of conjugated or direct bilirubin is unlikely to represent cholestasis from biliary atresia or other causes.6,7 Physicians should instead consider and evaluate for conditions that elevate conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin, notably HDN and sepsis, and repeat testing in several days to two weeks if a cause is not identified. If the conjugated or direct bilirubin level continues to increase, cholestasis is more likely.

Screening Recommendations

The goal of screening for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is to decrease the incidence of bilirubin toxicity while minimizing undue harm.4 However, developing evidence-based screening recommendations for use in high-income countries like the United States has been challenging because of the exceedingly low incidence of kernicterus, the primary patient-oriented outcome. No current screening test reliably identifies all newborns who will develop kernicterus.16

Universal screening for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia decreases emergency department visits for jaundice.27 In 2022, the AAP reconfirmed its recommendation for universal screening of newborns 35 weeks' gestational age or greater using TSB or TcB at 24 to 48 hours of life or before hospital discharge if occurring sooner.4 The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends universal screening during the first 72 hours of life.28

In an archived statement from 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force cites insufficient evidence that universal screening affects rates of kernicterus.16 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends measuring bilirubin only in newborns appearing jaundiced on examination.20 Screening all newborns for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, regardless of risk, increases rates of phototherapy, sometimes inappropriately. One large retrospective cohort study showed that only 56% of newborns who received phototherapy had a bilirubin level exceeding the recommended threshold from the then-current 2004 AAP guideline.29 There are also substantial costs to consider. The number needed to screen to prevent one case of kernicterus is estimated at 128,000 newborns, and the approximate cost to prevent that one case is $5.7 to $9.2 million.30,31

Despite conflicting guidelines on universal screening and limited evidence for patient-oriented outcomes, evaluating all newborns for neurotoxicity risk factors is important. It is reasonable to, at a minimum, obtain bilirubin levels in newborns at risk. Universal screening for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, as recommended by the AAP, is common in the United States and can be considered while acknowledging the risks of overtreatment.

SCREENING IN SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

Jaundice in newborns with HDN often presents earlier, sometimes in the first 24 hours after delivery. Newborns born to mothers who are blood group O, are Rh(D) negative, had a positive anti-erythrocyte antibody screening result during pregnancy, or have unknown results should have ABO blood group, Rh(D) status, and direct antiglobulin tests as soon as possible after birth via cord or peripheral blood. Obtaining TcB measurement six hours after delivery in newborns who have positive results on direct antiglobulin testing helps determine whether they need phototherapy within 24 hours of delivery.32 Infants with a bilirubin level of less than 3 mg per dL at six hours of life are highly unlikely to require phototherapy before 24 hours of life, whereas infants with a bilirubin level of 5.3 mg per dL [90.6 μmol per L] or higher are likely to need phototherapy and require ongoing, frequent bilirubin measurement.32 Newborns who test positive only for anti-Rh(D) antibodies and were born to mothers who received Rh0(D) immune globulin are not considered to have a positive direct antiglobulin test result.4

Next Steps

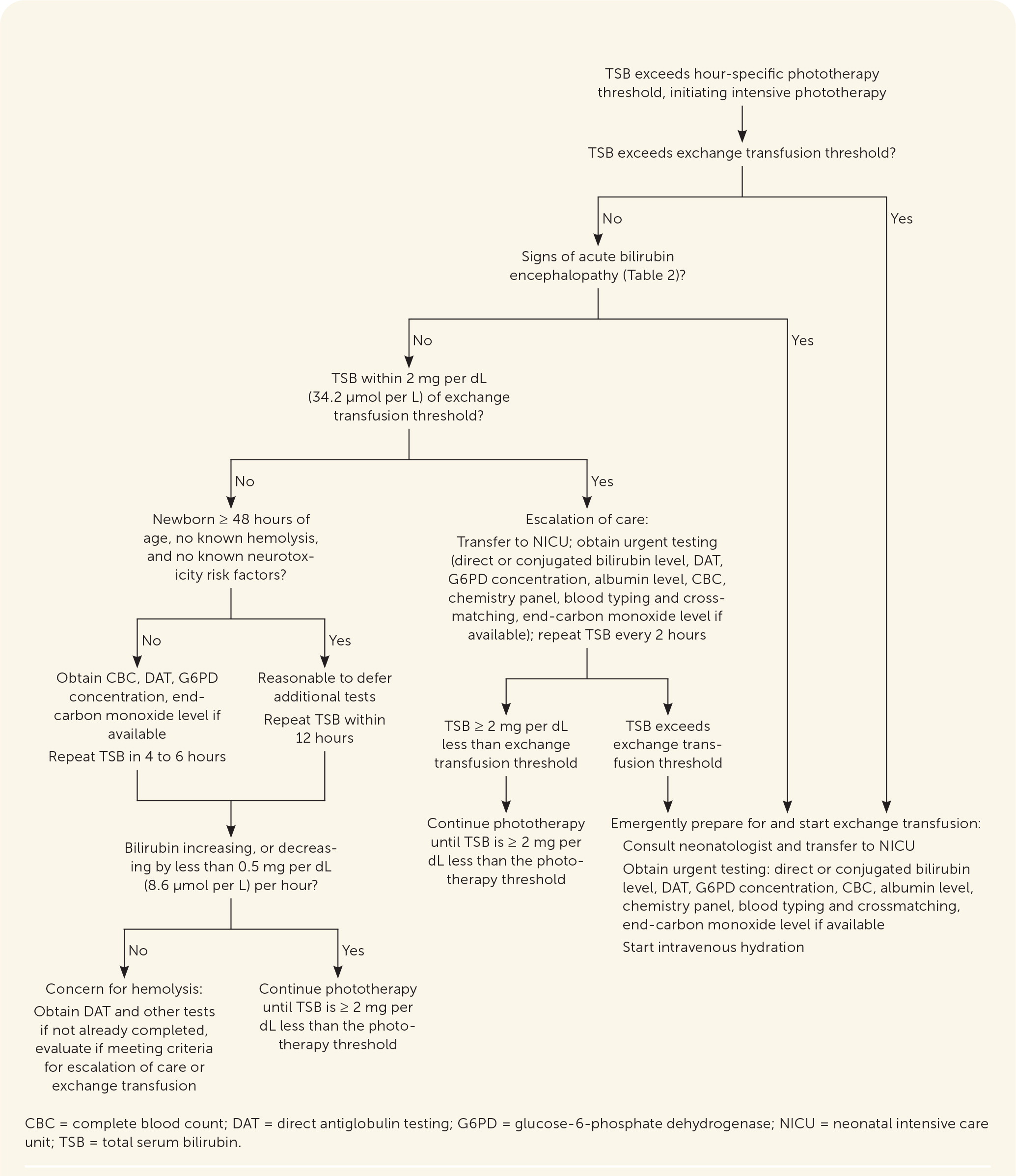

After assessing bilirubin levels, the difference between the measured bilirubin level and the hour-specific phototherapy threshold should be calculated to determine when to reevaluate an infant and repeat bilirubin measurements.4,33 Newborns with a smaller difference between measured bilirubin level and phototherapy threshold require more frequent follow-up. Online tools, including PediTools (https://peditools.org/bili2022) and BiliTool (https://bilitool.org), provide phototherapy thresholds, calculate the difference between measured bilirubin level and phototherapy threshold, and display recommendations. These tools have been updated to reflect the 2022 AAP guideline. Figure 1 summarizes an approach to the care of newborns with hyperbilirubinemia.4,33

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is the first-line treatment for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Absorbed light converts unconjugated bilirubin to lumirubin, one of its structural isomers. Lumirubin is then directly excreted via urine or stool, thereby bypassing the need for conjugation in the liver.34 Guidelines do not recommend direct or indirect sunlight as a reliable or safe treatment option.4,20

INITIATION

The AAP neonatal hyperbilirubinemia guideline provides hour-specific thresholds for initiation of phototherapy based on gestational age and the presence or absence of neurotoxicity risk factors.4 Newborns of younger gestational age and newborns with neurotoxicity risk factors have lower thresholds for initiating phototherapy.4 The phototherapy thresholds in the 2022 AAP guideline are modestly higher than in the 2004 guideline due to evidence that neurotoxicity occurs at bilirubin levels much higher than previously thought.1,4,10,16 The decision to start phototherapy is typically based on the TSB level.

METHODS

Traditional methods for phototherapy, including fluorescent and halogen bulbs, and newer methods, including LED and fiber-optic sources, are equally effective in lowering bilirubin levels, with no difference in the duration of phototherapy required or the need for exchange transfusion.35–37 Treatment is more effective when more skin is exposed and the light source is closer to the newborn.

| ≥ 38 weeks' gestational age |

| ≥ 48 hours of age |

| Newborn is clinically well with appropriate weight loss (no more than 10% of birth weight) and output (number of voids and stools in 24 hours equivalent to age of newborn in days) |

| No known neurotoxicity risk factors |

| No previous phototherapy |

| Total serum bilirubin no more than 1 mg per dL (17.1 μmol per L) greater than the phototherapy threshold for age in hours* |

| LED-based phototherapy device is available to bring home the same day |

| Ability to check total serum bilirubin daily after starting phototherapy |

RISKS

Phototherapy decreases the need for an exchange transfusion but has not been shown to decrease the incidence of kernicterus.16 Short-term risks of phototherapy include temperature instability, diarrhea, and physical separation of the newborn from the parents. Treatment may also prolong hospitalization.38

Long-term adverse effects include an increased risk of seizures, especially in males, at a rate of 2 to 7 per 1,000 newborns treated.39,40 Although data are conflicting, there may also be a small increased risk of cancers, including leukemia, renal cancer, and hepatic cancer, at a rate of 1 per 10,000 newborns treated.41–44 These risks highlight the importance of initiating phototherapy only in newborns who exceed the 2022 AAP thresholds. Subthreshold phototherapy is not recommended.45

LABORATORY TESTING AT THE INITIATION OF PHOTOTHERAPY

Newborns with a known hemolytic process or other neurotoxicity risk factor and those requiring phototherapy before 48 hours of life should have laboratory testing at the initiation of phototherapy, including a complete blood count, direct antiglobulin test if not already obtained, and a G6PD concentration.4,34,46 End-tidal carbon monoxide level is also helpful, if available, because higher levels can identify newborns with hemolysis due to causes other than HDN.4

Other testing can be deferred when initiating phototherapy in newborns 48 hours or older without known hemolysis. Almost all such newborns have a normal evaluation.46

ONGOING LABORATORY TESTING DURING PHOTOTHERAPY

Ongoing TSB monitoring is indicated during phototherapy. A repeat TSB level should be obtained in most newborns no more than 12 hours after starting phototherapy.4 However, TSB should be obtained four to six hours after initiating phototherapy in newborns with known or suspected hemolysis or other neurotoxicity risk factors.4,20

Bilirubin levels should decrease by 0.5 mg per dL (8.6 μmol per L) per hour in the first hours after initiation of phototherapy.34 If bilirubin is not decreasing as expected or is increasing despite treatment, hemolysis should be suspected and additional laboratory studies obtained if not already done.34,46

FEEDING DURING PHOTOTHERAPY

Newborns should breastfeed at least eight to 12 times per day, and breastfeeding support is important in the care of newborns with jaundice.4 Phototherapy may be interrupted briefly (up to 30 minutes at a time) to promote breastfeeding.47 However, mothers of newborns who develop jaundice are more than twice as likely to stop breastfeeding by one month of age compared with mothers of newborns without jaundice, and positive interaction and encouragement from health care professionals is one of the strongest predictors of ongoing breastfeeding.47,48

Newborns with hyperbilirubinemia due to suboptimal breast milk intake, as evidenced by weight loss of greater than 10% of birthweight or decreased urine and stool output, may benefit from supplementation to promote bilirubin excretion and shorten phototherapy duration. Supplementation with formula or expressed or donor breast milk should be considered using shared decision-making between parents and physicians.4

PHOTOTHERAPY DISCONTINUATION

Expert recommendations differ on when to stop phototherapy, but it is reasonable to discontinue when the TSB is at least 2 mg per dL less than the treatment threshold at phototherapy initiation.4,34 Infants who develop signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy, regardless of bilirubin levels, should continue phototherapy and be referred for exchange transfusion.4

Escalation of Care

Newborns within 2 mg per dL of the exchange transfusion threshold should immediately receive additional evaluation and treatment, including consultation with a neonatologist and transfer to the neonatal intensive care unit.4 Phototherapy should begin before the transfer, if not already initiated, along with intravenous hydration. Urgent laboratory testing should include TSB and direct or conjugated bilirubin level, direct antiglobulin test, complete blood count, albumin level, chemistry panel, blood typing and crossmatching, G6PD concentration, and end-tidal carbon monoxide level if available. The TSB level should be monitored every two hours until the bilirubin decreases to at least 2 mg per dL less than the exchange transfusion threshold or a transfer of care is achieved.4

EXCHANGE TRANSFUSION

Emergent exchange transfusion is recommended for newborns exceeding the exchange transfusion threshold or with signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy.4 Exchange transfusion involves slowly replacing the newborn's blood with donor red blood cells to remove bilirubin and antibodies that may be causing hemolysis.49 Exchange transfusion effectively lowers bilirubin, but it is unclear if it decreases rates of acute bilirubin encephalopathy or kernicterus because they already occur so rarely.4

The procedure should be performed in a neonatal intensive care unit because more than 10% of newborns will have a complication, including infection, electrolyte imbalances, transfusion reactions, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, necrotizing enterocolitis, or death.34 The mortality rate in newborns without hemolysis is 3 to 4 per 1,000 newborns treated and may be as high as 1% to 3% in newborns with hemolysis.50,51 Figure 2 summarizes phototherapy, escalation of care, and exchange transfusion.4,34,46

Follow-Up After Discharge

NEWBORNS NOT TREATED WITH PHOTOTHERAPY

All newborns should be discharged with a clear follow-up plan (Table 44). Newborns who have not previously received phototherapy or objective bilirubin assessment can follow up in one or two days.1,20 If a predischarge bilirubin level is available, the difference between the measured bilirubin level and the hour-specific phototherapy threshold is calculated to guide the follow-up plan.4,33

| Phototherapy threshold minus TcB or TSB | Discharge recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 – 1.9 mg/dL | Age < 24 hours | Delay discharge, consider phototherapy, measure TSB in 4 to 8 hours |

| Age ≥ 24 hours | Measure TSB in 4 to 24 hours* Options: Delay discharge and consider phototherapy Discharge with home phototherapy if all considerations in the guideline are met Discharge without phototherapy but with close follow-up | |

| 2.0 – 3.4 mg/dL | Regardless of age or discharge time | TSB or TcB in 4 to 24 hours* |

| 3.5 – 5.4 mg/dL | Regardless of age or discharge time | TSB or TcB in 1 to 2 days |

| 5.5 – 6.9 mg/dL | Discharging < 72 hours | Follow-up within 2 days; TcB or TSB according to clinical judgment† |

| Discharging ≥ 72 hours | Clinical judgment† | |

| ≥ 7.0 mg/dL | Discharging < 72 hours | Follow-up within 3 days; TcB or TSB according to clinical judgment† |

| Discharging ≥ 72 hours | Clinical judgment† | |

At the follow-up visit, assessment should include the newborn's weight (less than 10% weight loss from birth is expected), feeding (goal of eight to 12 feeds per day), urine and stool output (number of voids and stools per day should roughly correlate with newborn's age in days; stools should be transitioning from meconium to yellow and seedy), and screening for symptoms of bilirubin toxicity.4 Repeat bilirubin measurement is not needed at follow-up if the newborn is doing well clinically, has not been treated with phototherapy, and is at low risk of developing hyperbilirubinemia.

NEWBORNS TREATED WITH PHOTOTHERAPY

TSB is typically measured at follow-up in newborns treated with phototherapy who require repeat bilirubin assessment. TcB assessment is also reasonable if it has been at least 24 hours since phototherapy discontinuation.4,52 Table 5 lists follow-up recommendations after phototherapy.4,52,53 Keeping the newborn in the hospital to repeat bilirubin measurement is not necessary.53

| Timing of phototherapy | Discharge recommendations |

|---|---|

| During birth hospitalization | |

| Phototherapy before 48 hours of age or in newborns with a positive direct antiglobulin test result or other cause of hemolysis | Measure TSB in 12 to 24 hours |

| All other newborns requiring phototherapy during birth hospitalization | Measure TSB or TcB in 1 or 2 days |

| After birth hospitalization (all newborns) | Follow up in 1 or 2 days, measure TSB or TcB based on clinical judgment |

PROLONGED JAUNDICE

Further evaluation is needed for breastfed newborns who appear jaundiced at three to four weeks of age and formula-fed newborns who appear jaundiced at two weeks of age. The initial step is measuring direct or conjugated bilirubin level to assess for cholestasis.

Physicians should also review newborn screening results for genetic and metabolic causes of jaundice.4 Breastfed newborns with prolonged jaundice despite appropriate weight gain and stool and urine output likely have an inborn error of metabolism affecting bilirubin conjugation, commonly called breast milk jaundice. These newborns can continue to breastfeed, and families should be educated that this type of jaundice is benign and self-resolving, typically by three months of age.4,54

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Muchowski38; Moerschel, et al.11; and Porter and Dennis.55