Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(5):514-523

Patient information: See related handout on what could be causing dizziness.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Dizziness is a common but often diagnostically difficult condition. Clinicians should focus on the timing of the events and triggers of dizziness to develop a differential diagnosis because it is difficult for patients to provide quality reports of their symptoms. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes peripheral and central causes. Peripheral etiologies can cause significant morbidity but are generally less concerning, whereas central etiologies are more urgent. The physical examination may include orthostatic blood pressure measurement, a full cardiac and neurologic examination, assessment for nystagmus, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (for patients with triggered dizziness), and the HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination when indicated. Laboratory testing and imaging are usually not required but can be helpful. The treatment for dizziness is dependent on the etiology of the symptoms. Canalith repositioning procedures (e.g., Epley maneuver) are the most helpful in treating benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Vestibular rehabilitation is helpful in treating many peripheral and central etiologies. Other etiologies of dizziness require specific treatment to address the cause. Pharmacologic intervention is limited because it often affects the ability of the central nervous system to compensate for dizziness.

Family physicians commonly evaluate dizziness.1 Patients' descriptions of their symptoms are unreliable for establishing a diagnosis.2 The differential diagnosis can range from straightforward and self-limiting conditions to more serious conditions requiring further workup (Table 11,3). Physicians are encouraged to use a systematic approach to dizziness to diagnose and treat patients safely.4

| Cause | Clinical description |

|---|---|

| Peripheral | |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | Disorder of the inner ear characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo1 |

| Vestibular neuritis | Spontaneous episodes of vertigo caused by inflammation of the vestibular nerve or labyrinthine organs, usually from a viral infection |

| Meniere disease | Two or more episodes of vertigo lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours (definite) or up to 24 hours (probable) and fluctuating or nonfluctuating sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, or pressure in the affected ear3 |

| Central | |

| Vestibular migraine | Spontaneous episodes of vertigo associated with migraine headaches |

| Vertebrobasilar ischemia | Continuous spontaneous episodes of vertigo caused by arterial occlusion or insufficiency affecting the vertebrobasilar system |

| Other | |

| Peripheral | Acute coronary syndrome, anemia, aortic dissection, arrhythmia, behavioral health concerns, ectopic pregnancy, hormonal imbalance, infection, metabolic disorders, otosclerosis, pulmonary embolism, thyroid disease, vasovagal reflex |

| Central | Cerebellopontine angle tumors, craniocervical dissection, encephalitis, intracranial hemorrhage, meningitis, multiple sclerosis, seizures |

General Approach

Vertigo is a sensation of distorted self-motion when no self-motion is occurring. Dizziness is a sensation of disturbed or impaired spatial orientation without a false or distorted sense of motion.5 These symptoms are vague, presenting a diagnostic dilemma. Using the TiTrATE (timing of the symptoms, triggers that provoke the symptom, and targeted examination) mnemonic can help focus the assessment.5–7 This approach to the patient helps distinguish between benign and serious causes.

History

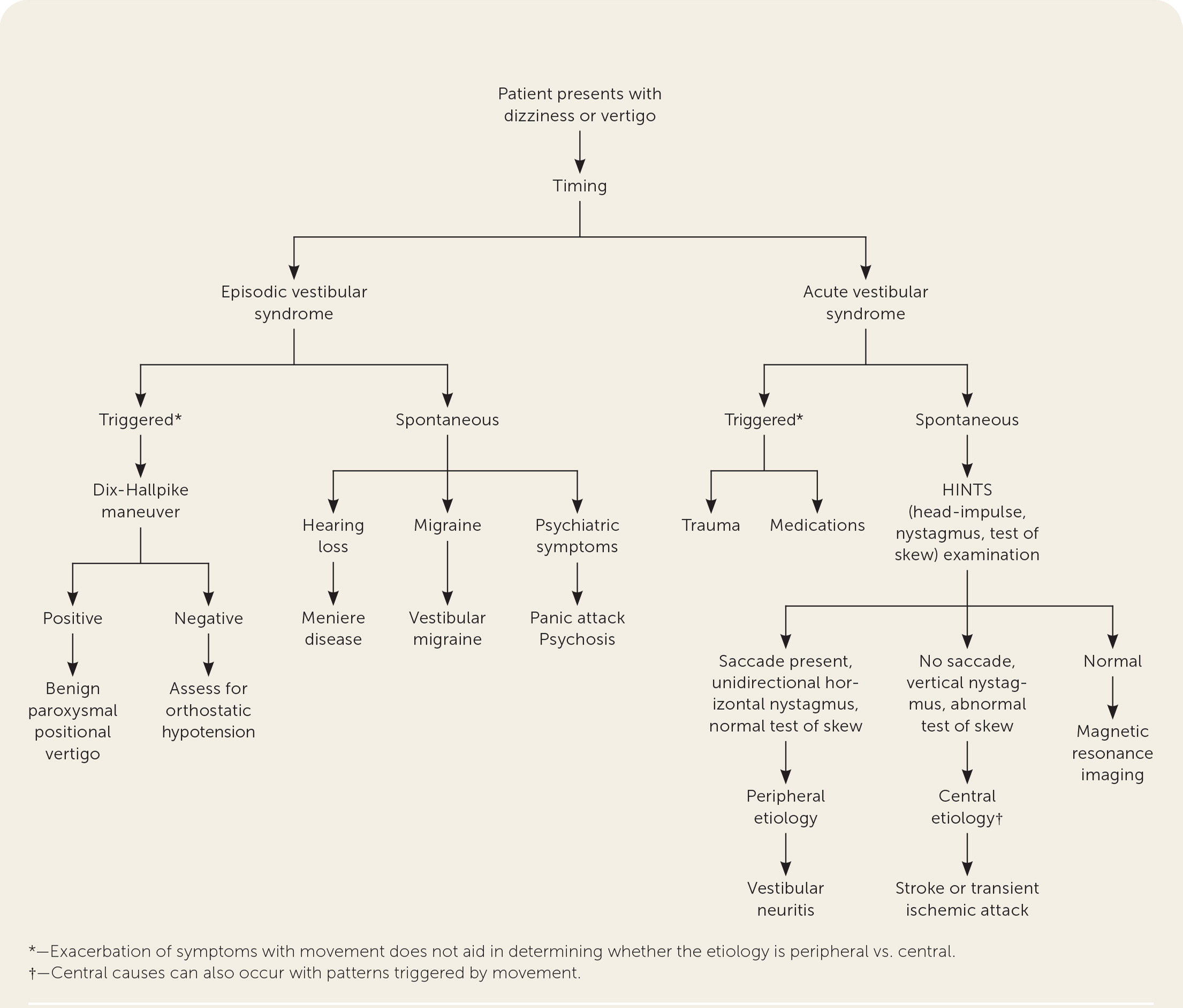

Timing (i.e., onset, duration, and evolution of the dizziness) can help distinguish between episodic and continuous dizziness. Episodic vestibular syndromes are clinical syndromes of transient vertigo, dizziness, or unsteadiness lasting seconds to hours. Acute vestibular syndromes are acute-onset, continuous vertigo, dizziness, or unsteadiness lasting days to weeks. Table 2 describes vestibular presentations of dizziness.5,7 Figure 1 can help in the assessment of dizziness.8

| Syndrome | Duration | Characteristics | Potential etiologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic vestibular syndrome | |||

| Triggered | Seconds to minutes | Asymptomatic at rest Physical examination (Dix-Hallpike) can be helpful in assessment Symptoms triggered by head motion or change in body position | Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo Orthostatic hypotension |

| Spontaneous | Minutes to hours | Head motion may worsen symptoms No obvious triggers Symptoms at rest | Cardiac arrhythmias Hypoglycemia Meniere disease Vertebrobasilar transient ischemic attack Vestibular migraine |

| Acute vestibular syndrome | |||

| Traumatic/toxic | Acute, typically one episode Resolves over days to weeks once exposure is stopped | Onset of symptoms in relation to exposure Physical examination less helpful due to temporal relationship to exposure | Drug intoxication Head trauma Medication adverse effects |

| Spontaneous | Acute, multiple episodes | No obvious traumatic events or toxic exposures Physical examination (HINTS [head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew]) can distinguish between central and peripheral etiologies | Brain stem or cerebellar stroke Listeria encephalitis Thiamine deficiency Vestibular neuritis |

After establishing timing, clinicians should determine if the symptoms are triggered or spontaneous. Triggers are actions, movements, or situations that provoke the onset of dizziness in patients with intermittent symptoms, but they do not differentiate peripheral from central etiologies.6 Episodic vestibular syndromes can be triggered or spontaneous. For example, patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo are often triggered by changes in their position. Patients with orthostatic hypotension may describe symptoms when triggered by moving from a sitting or supine to a standing position. Meniere disease is an example of episodic vestibular syndrome that is spontaneous but not triggered.3 Vestibular migraine is another example of spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome and manifests as vertigo in patients with a history of migraines.7 Panic attacks can present as spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome.

Acute vestibular syndrome can also be characterized as triggered or spontaneous. Triggered acute vestibular syndrome is usually caused by toxins, such as medications, or trauma. A medication and toxic exposure history can aid in diagnosis. Table 3 lists medications and substances associated with dizziness.8,9 Traumatic brain injury, tympanic membrane rupture, whiplash, skull fracture, vertebral artery dissection, and other trauma can trigger acute vestibular syndrome.10 Etiologies for spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome include vestibular neuritis, transient ischemic attack, or stroke, which can be determined through a physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging.

| Medication | Causal mechanism |

|---|---|

| Antiarrhythmic, class 1a Antidementia agents Antihistamines (sedating) Antihypertensives Antidepressants (e.g., ketamine [Ketalar])9 Anti-infectives: anti-influenza agents, antifungals, quinolones Antiparkinsonian agents Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder agents Digitalis glycosides Dipyridamole Narcotics Nitrates Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors Skeletal muscle relaxants Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors Urinary anticholinergics | Cardiac effects: hypotension, other arrhythmias, postural hypotension, torsades de pointes |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants Urinary anticholinergics and gastrointestinal antispasmodics | Central anticholinergic effects |

| Alcohol Antiseizure medications Benzodiazepines Lithium | Cerebellar toxicity |

| Antidiabetic agents Beta adrenergic blockers | Hypoglycemia |

| Aminoglycosides Antirheumatic agents | Ototoxicity |

| Anticoagulants Antithyroid agents | Bleeding complications (anticoagulants), bone marrow suppression (antithyroid agents) |

Physical Examination

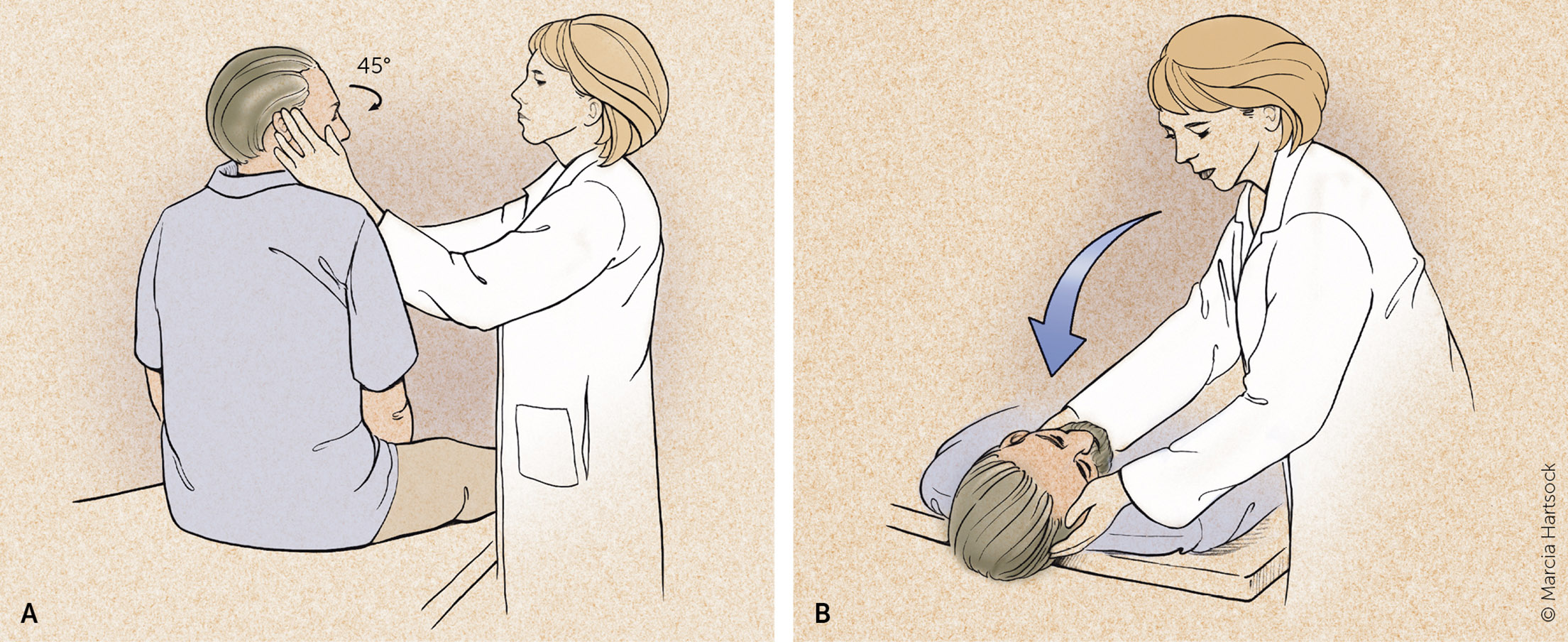

Patients with triggered episodic vestibular syndrome can be further evaluated with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and orthostatic vitals.8,11 Orthostatic hypotension is a sustained reduction in systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure reduction of 10 mm Hg within three minutes of standing from a supine or sitting position.12 The Dix-Hallpike maneuver can diagnose benign paroxysmal positional vertigo1 (Figure 213). Transient upbeat-torsional nystagmus during the maneuver suggests benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, especially in the absence of spontaneous or gaze-evoked nystagmus.2 This examination should be performed only when patients have triggered episodic vestibular syndrome. However, a negative result on the Dix-Hallpike maneuver does not eliminate benign paroxysmal positional vertigo if the timing and triggers are consistent with that diagnosis.14

If there is a concern for spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome due to a central etiology, a full neurologic examination should be completed in an inpatient or emergency department setting.7 The HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can help distinguish central from peripheral causes of vertigo8 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84waYROlI4U). When the HINTS examination is performed by trained clinicians, the sensitivity and specificity to identify central causes of vertigo, such as an acute stroke, are 97% and 96%, respectively.15,16

HEAD-IMPULSE

While the patient is seated, the head is thrust 10 degrees to the right and left while the patient's eyes are fixed on the examiner's nose. If a saccade (rapid movement of both eyes in which the gaze overcorrects to keep focused on the examiner) occurs, the etiology is likely peripheral.11 No eye movement strongly suggests a central etiology.16 This is helpful only if the patient has ongoing symptoms at the time of the examination.

NYSTAGMUS

The examiner should assess for spontaneous nystagmus, the direction of the nystagmus, and the ability of the nystagmus to be suppressed. Nystagmus that is unidirectional (i.e., does not change direction with shifts in gaze) and horizontal suggests a peripheral cause of vertigo. This type of nystagmus tends to increase in velocity as the patient looks in the direction of the nystagmus and decreases when looking in the opposite direction. Alternatively, primarily vertical, torsional, or bidirectional nystagmus suggests a central cause of vertigo.2 Suppression of nystagmus with visual fixation typically suggests peripheral vertigo. Visual fixation is tested by asking the patient to focus on an object in the room and then placing a blank sheet of paper in front of the patient's face. A nystagmus that terminates when focusing on an object but returns after removing the blank sheet of paper is suppressible.11

TEST OF SKEW

Test of skew is assessed by asking the patient to look straight ahead, then covering and uncovering each eye. Vertical deviation of the covered eye after uncovering is an abnormal result suggesting central pathology such as a brainstem stroke.16

Laboratory Testing and Imaging

Most patients presenting with dizziness do not require laboratory testing; however, some differential diagnoses require laboratory tests if there is a high index of suspicion.

Patients with symptoms suggestive of cardiac disease should have electrocardiography, Holter monitoring, 28-day event monitoring, and possibly carotid Doppler ultrasonography. However, routine troponin testing in older patients with weakness, dizziness, and fatigue should be avoided due to the high level of false-positive results and the rare association of these nonspecific symptoms with acute coronary syndrome in this population.17

Although routine imaging is not indicated for peripheral causes, clinicians should consider computed tomography of the temporal bone or magnetic resonance imaging of the head and internal auditory canal for patients with hearing loss or aural fullness. Computed tomography can evaluate the bony labyrinth and detect fractures, bony erosions, and superior semicircular canal dehiscence. If central causes of dizziness are suspected, such as neoplasms, Chiari malformations, or demyelinating lesions, clinicians should consider magnetic resonance imaging of the head and internal auditory canal with and without intravenous contrast media.18

Peripheral Etiologies

Dizziness is most commonly caused by a peripheral etiology. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, vestibular neuritis, and Meniere disease are the most common peripheral causes of dizziness.1

BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONAL VERTIGO

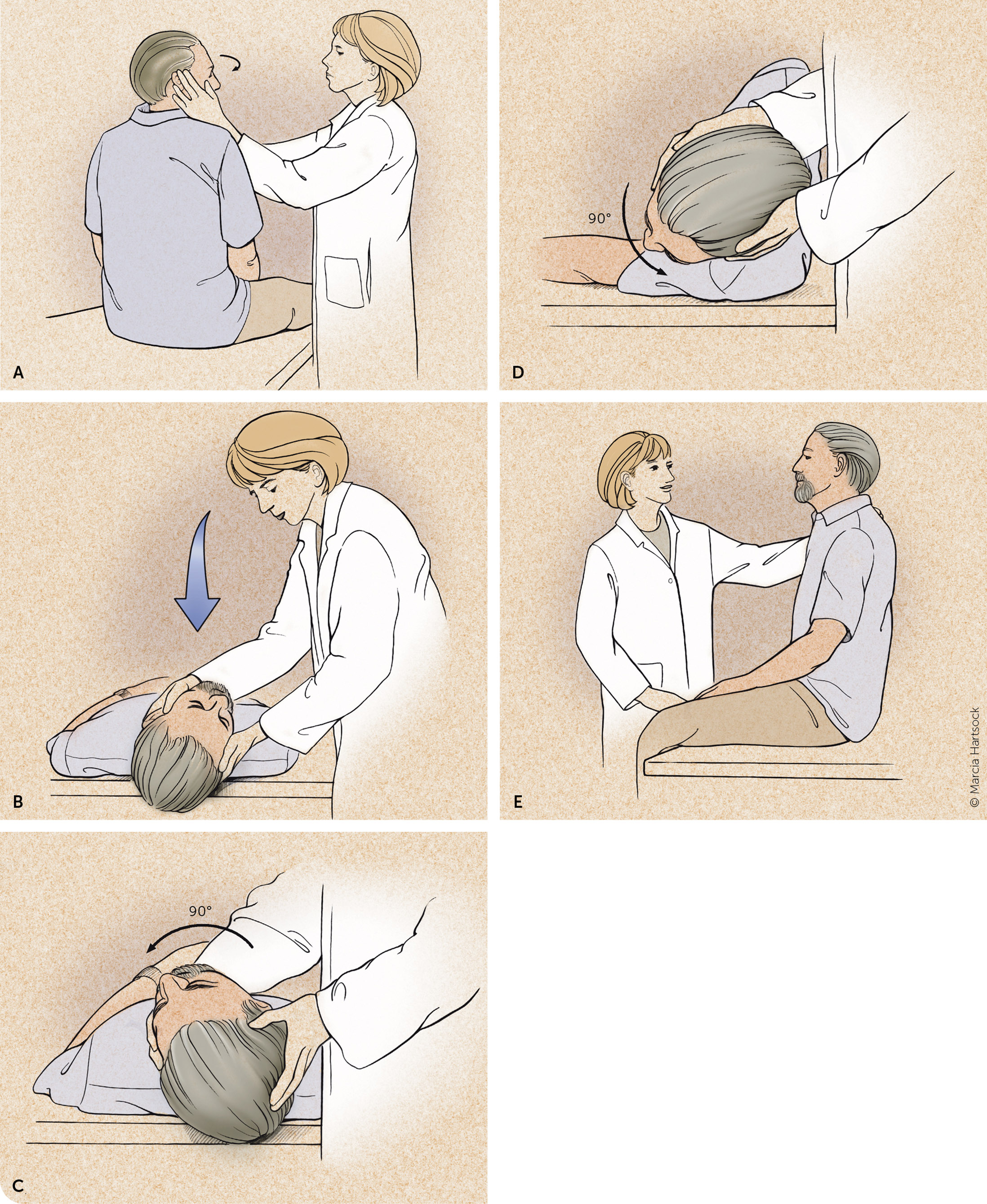

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, the most common peripheral etiology, occurs between 50 and 70 years of age and affects more women than men.14 It results from loose stones, called canaliths, that get stuck in the semicircular canals. In up to 70% of cases in older patients, there is no apparent traumatic, ischemic, infectious, or inflammatory cause; however, young adults present with head trauma as the leading risk factor.19 The most effective treatment for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is repositioning procedures,19,20 such as the Epley maneuver (Figure 313; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9SLm76jQg3g). Repositioning maneuvers are more effective when certain canals are affected. Epley maneuvers are effective for posterior canal canaliths; however, other maneuvers are more effective at repositioning stones in the horizontal canal.14 The success rate for the Epley maneuver is nearly 100%.19 Some patients, especially those with trauma-related benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, require more repetitions of the repositioning maneuvers.21 If there is no improvement with repeated maneuvers, or the patient develops atypical nystagmus or nausea, a different cause should be considered.14

In addition to repositioning, evidence supports vestibular rehabilitation as safe and effective. It includes activities to help patients coordinate their balance, vision, and muscle movements to decrease the impact of dizziness and imbalance. The best long-term outcomes involve a combination of vestibular rehabilitation and repositioning maneuvers.22 Patients refractory to these treatments may need to be evaluated by otolaryngology or neurology. Pharmacologic treatments, including antihistamines and benzodiazepines, are generally not indicated because they interfere with the patient's ability to centrally compensate, which increases the risk of falls.11 One meta-analysis of seven studies found that replacing vitamin D in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and vitamin D deficiency lowered recurrence.23

VESTIBULAR NEURITIS

The second most common peripheral etiology of dizziness is vestibular neuritis, which is often the result of a viral infection and is a clinical diagnosis.24 Vestibular neuritis occurs most often in patients between 30 and 50 years of age. It can cause severe vertigo accompanied by nausea and nystagmus. A physical examination shows fast-paced horizontal nystagmus toward the affected side and an abnormal gait with patients falling to the affected side.24 The HINTS examination can detect a hypofunctioning vestibular-ocular reflex that can be present in vestibular neuritis. Positioning maneuvers are ineffective, and the Dix-Hallpike maneuver does not usually trigger symptoms. Symptoms resolve after a few days, but some patients experience months of reoccurring symptoms.19 Some patients develop benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.25 Attacks initially last one to two days and progressively get shorter until resolved. If this does not occur, a different diagnosis should be considered.26

The mainstay of treatment for vestibular neuritis is reassurance, explaining the expected disease course and resolution, symptomatic treatment, and vestibular rehabilitation.9,11 Vestibular rehabilitation is time-consuming to perform in the office, but using an interprofessional approach with physical therapy may allow others to do the teaching.27

Antiemetic medications can be used for symptomatic treatment, but it is important to note that they often block central compensation. Antihistamines, antiemetics, and benzodiazepines treat vertigo associated with nausea caused by vestibular neuritis.9 Antiviral medications are not effective.24 Steroids have no proven role and are not recommended.28

MENIERE DISEASE

Meniere disease is an inner ear disorder with multifactorial etiology that presents with recurrent and spontaneous episodes of vertigo, including hearing loss, tinnitus, and unidirectional, horizontal nystagmus.29 Meniere disease has a biphasic occurrence affecting patients in their 20s and 60s.30 The underlying pathology is hypothesized to be pressure from excess endolymphatic fluid, leading to inner ear dysfunction.29 Clinicians should order an audiogram when assessing a patient for Meniere disease.3 Conventionally, treatment includes limiting patients to less than 2,000 mg of salt per day, reducing caffeine intake, and limiting alcohol to one drink per day; however, this guidance is not supported by evidence.31 Evidence is insufficient to recommend treating patients with diuretics or transtympanic injections of gentamicin or glucocorticoids.11,29

Central Etiologies

VESTIBULAR MIGRAINE

Vestibular migraine is the most common type of spontaneous episodic vestibular syndrome.11 It has a prevalence of 2.7% in adults, is more common in females (64.1%), and occurs at a mean age of 40 years.32 Vestibular migraines occur with a headache or history of headaches, and nystagmus may be vertical or horizontal. Diagnostic criteria include recurrent vestibular symptoms (at least five episodes) lasting from five minutes to 72 hours and a previous or current migraine. Diagnostic criteria for evaluation are listed in Table 4.33 Clinicians should perform magnetic resonance imaging to establish the diagnosis when a central etiology is suspected. Patients with hearing loss or tinnitus should have an audiology evaluation.34

Vestibular migraine

|

Probable vestibular migraine

|

No consensus exists on treatment or preventive therapies. Lifestyle modifications to avoid migraine triggers include adequate rest, physical exercise, dietary modifications, and stress management. Abortive agents like triptans, analgesics, and antiemetics can be helpful in treatment. Preventive medications for migraines, such as topiramate, amitriptyline, and propranolol, may also reduce occurrence.34

VERTEBROBASILAR ISCHEMIA

| Misleading assumptions | Pearl |

|---|---|

| True vertigo implies an inner ear disorder. | Do not rely on quality of symptoms; focus on timing and triggers. |

| Vertigo worsening with head movements implies a peripheral cause. | Differentiate triggers from exacerbating factors because head movement could exacerbate central and peripheral causes. |

| Hearing loss or tinnitus implies a peripheral cause. | With these auditory symptoms present, rule out a central cause before assuming a peripheral cause. |

| Headache accompanying dizziness implies vestibular migraine. | Be aware that not every headache presenting with dizziness is a vestibular migraine and could indicate vascular pathologies such as an aneurysm. |

| Strokes causing dizziness or vertigo must also present with limb ataxia or other focal signs. | Findings on the HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination are more specific and sensitive to rule in stroke than presence of limb ataxia or other focal signs. |

| Young patients have migraine rather than stroke. | Do not overfocus on age and vascular risk factors; consider vertebral artery dissection in young patients. |

| CT is needed to rule out cerebellar hemorrhage in patients with isolated acute dizziness or vertigo. | Intracerebral hemorrhage rarely manifests as benign dizziness or vertigo. |

| CT is useful to search for acute posterior fossa stroke. | Recognize the limitations of imaging, especially CT. |

| A negative diffusion-weighted MRI rules out posterior fossa stroke. | Recognize the limitations of imaging, even diffusion-weighted MRI; consider repeat testing in 48 hours if negative. |

Vertebrobasilar ischemia usually presents as spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome but should be considered in the differential for all types of vertigo. Because approximately 10% to 20% of patients with spontaneous acute vestibular syndrome have cerebellar or brainstem ischemia,5 clinicians should be confident in their ability to perform an accurate HINTS examination or should refer the patient promptly to the appropriate expert.36 The HINTS examination can identify patients in whom there is a concern for vertebrobasilar ischemia. The evidence does not support using neuroimaging as the only tool for ruling out stroke and other causes of dizziness.37

Other Etiologies

Other etiologies include peripheral etiologies such as otosclerosis, acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, arrhythmia, pulmonary embolism, vasovagal reflex, ectopic pregnancy, infection, anemia, hormonal imbalance, thyroid disease, metabolic disorders, and behavioral health concerns,10 which can cause dizziness and should be considered in addition to the conditions in Figure 1.8 Other central etiologies of dizziness include craniocervical dissection, intracranial hemorrhage, multiple sclerosis, cerebellopontine angle tumors, seizure, encephalitis, meningitis, and seizures.10

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Muncie, et al.8; and Post and Dickerson.1

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms dizziness, vertigo, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, and vestibular. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched, including the Essential Evidence Plus Summary provided by Mark Ebell, deputy editor. Search dates: May 5, 2022 and April 5, 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Editor's Note: After this article went to print, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine published a guideline, GRACE 3-Acute Dizziness and Vertigo in the Emergency Department. The recommendations are summarized in an accessible infographic.

Although most dizzy patients have a benign cause, a small proportion will have a stroke or other more dangerous central lesion. An appropriate physical examination can distinguish benign from potentially urgent causes when performed accurately. The guideline highlights two important physical examination maneuvers and raises an important question about training.

- Finger rub: For patients presenting with continuous vertigo, the finger rub is a useful addition to the HINTS exam ("HINTS plus"). New hearing asymmetry on finger rub—even if the other three components of HINTS are consistent with peripheral vertigo—is suggestive of central stroke and the patient should be referred for MRI/MRA.

- Gait assessment: The review reminds us that gait assessment is an important part of the neurologic examination both for patients with continuous vertigo and for those with spontaneous episodic vertigo. With either presentation, significant gait ataxia raises the probability of a central lesion.

The guideline stresses that physical examination maneuvers to diagnose dizziness are inaccurate when performed incorrectly or without appropriate training. It acknowledges, however, that there is no consensus on what type of training ensures competence.—Laura Blinkorn, MD, Medical Editing Fellow