Even an old patient can be new.

Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10(8):33-36

New patient visits used to be easy to distinguish from those with established patients. A new patient was someone you had not previously seen or perhaps someone for whom you did not have a current medical record. Today, like so many other aspects of health care delivery, differentiating between new and established patients and coding your services accordingly has become more complex.

By CPT definition, a new patient is “one who has not received any professional services from the physician, or another physician of the same specialty who belongs to the same group practice, within the past three years.” By contrast, an established patient has received professional services from the physician or another physician in the same group and the same specialty within the prior three years.

KEY POINTS

New patient visits require more work than established patient visits at the same level, and this is reflected in the coding requirements as well as the reimbursement for new patient visits.

A key to differentiating between new and established patients is understanding two terms used in CPT’s definition of a new patient: “professional services” and “group practice.”

Medicare’s definition of a new patient is slightly different than CPT’s.

The distinction between new and established patients applies only to the categories of evaluation and management (E/M) services titled “Office or Other Outpatient Services” and “Preventive Medicine Services,” but as a family physician, most of the codes you submit fall into these categories, and the definition is hard to incorporate into your coding habits. This article will explain why the difference matters and describe an approach you can use to make the definition easier to apply.

The key differences

The reason for learning to distinguish new patients from established patients, apart from following coding guidelines, is that it enables you to be reimbursed for the additional work that new patient visits require (see “Documentation requirements”).

DOCUMENTATION REQUIREMENTS FOR NEW- AND ESTABLISHED-PATIENT OFFICE VISITS

| History | Exam | Medical decision making | Typical face-to-face time (minutes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99201 | Problem-focused | Problem-focused | Straightforward | 10 |

| 99202 | Expanded problem-focused | Expanded problem-focused | Straightforward | 20 |

| 99203 | Detailed | Detailed | Low | 30 |

| 99204 | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | Moderate | 45 |

| 99205 | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | High | 60 |

| History | Exam | Medical decision making | Typical face-to-face time (minutes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99211 | Not required | Not required | Not required | 5 |

| 99212 | Problem-focused | Problem-focused | Straightforward | 10 |

| 99213 | Expanded problem-focused | Expanded problem-focused | Low | 15 |

| 99214 | Detailed | Detailed | Moderate | 25 |

| 99215 | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | High | 40 |

For the new patient codes, the required components and the relative value units (RVUs) are greater than for established patient codes at the same level (see “Office visit RVUs”). So in some cases, not distinguishing new patients from established patients amounts to shortchanging yourself. For example, a visit that produces a detailed history, detailed exam and decision making of low complexity qualifies as a level-IV visit if the patient is established and a level-III visit if the patient is new. The established patient visit amounts to 2.17 RVUs ($79.82), while the new patient visit amounts to 2.52 RVUs ($92.69).

| New patients (99201–99205) | Established patients (99211–99215) | |

|---|---|---|

| Level I | .95 | .56 |

| Level II | 1.70 | .99 |

| Level III | 2.52 | 1.39 |

| Level IV | 3.59 | 2.17 |

| Level V | 4.58 | 3.18 |

Source: Medicare resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS).

Another important difference between the codes is that the new patient codes (99201–99205) require that all three key components (history, exam and medical decision making) be satisfied, while the established patient codes (99211–99215) require that only two of the three key components be satisfied. Because the criteria for coding problem-oriented new patient visits are more stringent, there are also cases where the same service components would yield an established patient code with more RVUs than the appropriate new patient code. For example, a visit that includes an expanded problem-focused history, detailed problem-focused exam and moderate complexity decision making would qualify as a level-II new patient visit (1.70 RVUs) but a level-IV established patient visit (2.17 RVUs).

Problem-oriented encounters for both new and established patients can also be coded based on the total time spent with the patient if counseling/coordination of care constitutes more than 50 percent of the total encounter time. The times associated with the new patient services, however, are higher than for the established patient encounters. (See “Time Is of the Essence: Coding on the Basis of Time for Physician Services,” FPM, June 2003, page 27.)

Preventive medicine encounters all require a comprehensive history and exam, and the codes are selected according to the age of the patient. The RVUs vary according to the level of physician work associated with performing comprehensive evaluations for the different age ranges (see “Preventive visit RVUs”).

| New patients (99383–99387) | Established patients (99393–99397) | |

|---|---|---|

| 5–11 years old | 2.90 | 2.30 |

| 12–17 years old | 3.15 | 2.55 |

| 18–39 years old | 3.15 | 2.58 |

| 40–64 years old | 3.70 | 2.85 |

| 65+ years old | 4.01 | 3.14 |

Source: Medicare resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS).

Defining “professional services”

Varying interpretations of what constitutes a “professional service” have been a source of confusion for practices trying to determine which patients qualify as new. CPT 2001 clarified the matter by defining professional services as “those face-to-face services rendered by a physician and reported by a specific CPT code(s).” The key phrases are “face-to-face” and “reported by a specific CPT code(s).”

Suppose you provided the interpretation of an ECG for an inpatient you did not actually meet in person. When you see the patient in your office (assuming this occurs within the next three years), you would report the E/M service you provide using a new patient code since there was no face-to-face encounter during the inpatient stay.

Consider the patient who is new to the community and needs a refill of her oral contraceptives. You agree to call in a prescription that will meet her needs until she can be seen in your office the following week. When you see her for her well-woman visit, you report a new patient preventive medicine service code since you did not have a face-to-face encounter with the patient when calling in her prescription.

If you are in solo practice, all you need to remember to differentiate new patients from established ones is whether you provided a face-to-face service within the last three years. The situation is different, however, for group practices.

Defining “group practice”

Although groups with multiple practice sites may operate independently, with each caring for its own patient population and maintaining its own medical records, they are considered a single group if they have the same tax identification number.

In a single-specialty practice, the patient’s encounter should be reported with a code in a new patient category only if no physician or other provider who reports services using CPT codes in that group has seen the patient within the last three years. For example, let’s say your partner saw a patient who is new to your practice in the emergency department (ED) over the weekend. The following week you see the patient in the office. Since someone else in your practice has seen the patient within the last three years, you have to use an established patient code. This is the case even though the patient had not been seen in the office and there was not an established medical record there.

In a multispecialty practice, a patient might be considered new even if he or she has received care from several other physicians in the group and a medical record is available. The distinguishing factor here is the specialty designation of the provider. For example, take a patient who has been seen regularly by the pediatrician in your group. The patient is now 18 years old and wants to transfer care to a family physician in the same group. When she sees the family physician, she’ll qualify as a new patient because the family physician is in a different specialty than her previous physician. This is the case even though the family physician might be treating her for an existing problem and referring to her established medical record.

Medicare has a list of specialty and sub-specialty designations it recognizes for payment purposes. Other payers may use this same list or may recognize more areas of expertise based on credentialing information.

When you change practices

Consider this scenario: Suppose you leave the practice where you have been working for a number of years to join a new group in a nearby community. Some of your patients transfer their care to the new practice and see you within three years of their last visits. You would report these encounters using an established patient code because, although you are practicing in a new group, you have provided professional services to the patient during the last three years. Note that whether the patient has transferred his or her medical records to your office and how long you may have had those records is irrelevant. The amount of time that’s passed since your last encounter with the patient is the determining factor.

Visits with patients who do not transfer care and are seen by another family physician in the original group within the three-year time frame are reported as established patient encounters. In this instance, the patient’s status is determined by the group identification, the time frame since the last encounter and the specialty of the physician providing care.

When one group provides coverage for another physician group, the patient encounter is classified as it would have been by the physician who is not available. For example, let’s say your practice provides coverage for a solo physician in your community. While the physician is out of town, you see one of her patients. As long as the physician who is out of town has seen the patient in the last three years, you have to report the service using an established patient code. This is true even if you are unfamiliar with the patient, clinical information is not available and the office staff does not have basic demographic information.

Special considerations for Medicare patients

A slightly different approach may be taken when Medicare patients are involved. Medicare has stated that a patient is a new patient if no face-to-face service was reported in the last three years. The group practice and specialty distinctions still apply, but “professional service” is limited to face-to-face encounters. Therefore, if you see a Medicare patient whom you have seen within the last three years, you must report the service using an established patient code. On the other hand, if a lab interpretation is billed but no face-to-face encounter took place, the new patient designation might be appropriate.

Consultations vs. new patient visits

If a patient is sent to you for an opinion or advice, the encounter may be a consultation service rather than a new patient encounter. CPT defines a consultation as “a type of service provided by a physician whose opinion or advice regarding evaluation and/or management of a specific problem is requested by another physician or other appropriate source.” For example, if you are asked to see a patient for a pre-operative clearance or for evaluation of a medical problem, the appropriate category might be consultation services. Since the same consultation codes apply to both new and established patients, it is not necessary to apply the new patient definition.

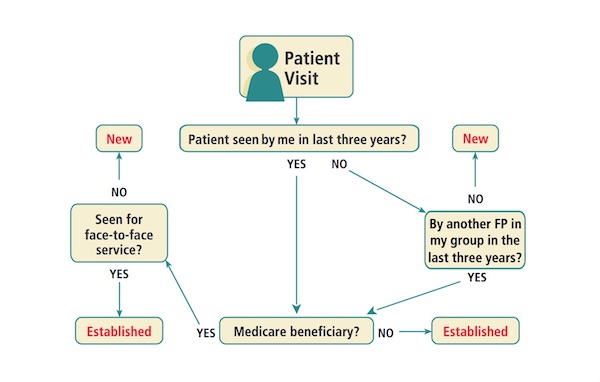

Decision tree for determining if a patient is new or established

Getting it right

The decision tree will prompt you to ask yourself a series of questions that will help you determine whether to code a new or established patient visit.

Getting it right can help ensure that you get paid appropriately for your services and keep your practice audit-proof.