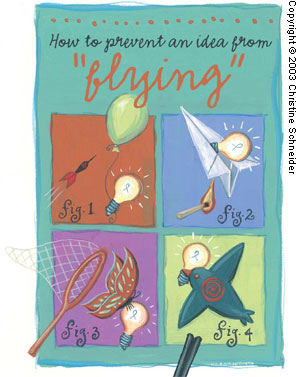

Three common mistakes will ensure your good ideas never fly.

Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10(8):39-42

“It must be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to plan, more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to manage, than the creation of a new system. For the initiator has the enmity of all who would profit by the preservation of the old institutions and merely lukewarm defenders in those who would gain by the new ones.”

– Machiavelli

How many times have you seen what you knew was a great idea fail miserably? Why do some ideas translate into sustainable change while others fall flat? The planning and guidance of change within organizations is called “change management,” and although its concepts are better known in the business community, they offer many useful points for the medical community. In fact, they could have helped our organization implement a diabetes management program, had we known about them at the time. The program was designed to help us meet one of the inspection requirements of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. It was mandated by our hospital CEO, who appointed an interdisciplinary team of 10 people (including myself, the “physician champion”) to sift through and apply national diabetes guidelines at our local level. Our multidisciplinary team spent nine months completing the mandate and, at that point, was ready to implement the program and reap the fruits of our labor. But we didn’t reap much. Here’s why.

KEY POINTS

To implement change in any organization, you must first change individuals’ behavior, not just their level of knowledge, through interpersonal, face-to-face communication and feedback.

When it comes to change management, remember the old saying: “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.”

The change agent plays a crucial role in the change process but must eventually help the organization transition away from reliance on the change agent to institutionalization of the innovation.

Mistake #1: Improve knowledge, but not behavior

The change-management literature emphasizes that changing individuals’ behavior is ultimately more important than changing their level of knowledge or their attitude. In other words, it matters more what people do than what they know. Behavior is best affected by interpersonal, face-to-face communication and feedback. Large group lectures, mass media and computer-based self-training may be adequate to improve knowledge, but they are less helpful in affecting behavior.

One of the key mistakes our diabetes group made was to assume that knowledge transmission alone would be sufficient for success and to focus our energy on traditional didactic lectures. While knowledge transmission is an important part of change management, it’s only the first stage in what Everett Rogers explains is a five-stage process:1

• Stage one: Knowledge transmission. Transmission requires more than simply providing technical information about the innovation; it also consists of communicating the underlying theory behind the innovation. Our diabetes team did a decent job of laying out the rationale for how the guidelines function and why they provide better patient outcomes than the current nonstandardized approach to diabetes management, but that wasn’t enough.

• Stage two: Persuasion. The primary goal of persuasion is to create a tension between the current process and the proposed innovation, between “what is” and “what could be.” Persuasion efforts must clearly lay out the relative advantages of the desired change, explain why the change is needed now, demonstrate that the change has been effective for others who have tried it and address “what’s in it for me.” Persuasion can also be accomplished by allowing individuals to experiment with the change and see for themselves whether it works. Solely bashing the status quo or hyping the preferred reality will not generate enough tension to spark change. Here, our group made critical mistakes, operating under the false assumption that, since our CEO had mandated use of the diabetes guidelines, we did not have to market or persuade anyone of the “rightness” of our cause.

• Stage three: Decision making. The decision-making stage is when the innovation will either be adopted or rejected on two distinct levels: the organizational level and the individual level. If the organization and the individual are discordant, obvious turmoil results. In our situation, the decision to adopt the diabetes guidelines at an organizational level was a predefined outcome because the CEO had mandated it; however, the decision to adopt the guidelines at the individual level was not. This became clear to us when we conducted a chart review in the residency clinic and found the guideline tools absent from the vast majority of charts related to diabetes visits.

• Stage four: Implementation. The implementation stage is when individuals move from decision to action. To keep the momentum of the change as it is being implemented, groups need early and frequent feedback and incentives to continue supporting the change. As is true with many medical therapies, the change period is often worse than the status quo. Only later, once the change becomes more routine, do the real benefits begin to accrue. Our diabetes improvement program never fully made it to the implementation stage due to the mistakes noted previously.

• Stage five: Confirmation. During the confirmation stage, individuals are seeking reinforcement that their decision to implement the change was correct. Their initial decision to either adopt or reject the innovation may be reversed depending on the group’s experience test-driving (or living without) the innovation. The confirmation stage continues for an indefinite period of time.

Mistake #2: Assume a standard response to change

Another key concept of change management is that people do not adopt change at the same rate. They can be categorized into five different groups, or “adopter categories,” based on when they tend to embrace innovation.1

1. The innovators (5 percent). The innovators are the leading-edge adopters. They are venturesome and rarely need much prompting to adopt new ideas and will seem to be your most natural allies. However, the problem with innovators is that they can be perceived as too radical by the rest of the group. Thus, their role in the diffusion of innovation may be limited.

2. The early adopters (10 percent). The early adopters are well read, well connected and respected in the organization. They seek innovations, are open to change and have a “big picture” view of the organization. To successfully promote innovation, you’ll need the help of the early adopters and should take steps to engage them – but the next group is even more important.

3. The early majority (35 percent). The opinion leaders of the organization are typically part of the early majority, whose support is crucial for change to succeed. Opinion leaders are not necessarily in formal positions of power; rather they have authority based on their technical competence, social accessibility or conformity to the organization’s values. Identify who these people are in your organization, and make sure you speak to their needs as you try to implement change.

4. The late majority (35 percent). If you gain the support of the early majority, the late majority (those individuals who prefer the status quo) will usually fall in line. Still, it’s good to keep them informed early in the process and address their barriers to change to secure their eventual buy-in.

5. The laggards (15 percent). This group may never be interested in change. Although your change can reach critical mass even without the support of the laggards, do not ignore them. Instead, keep them well informed from the outset to make buy-in possible down the road.

Our diabetes working group was not cognizant of these adopter categories when designing our program. In hindsight, we could have used adopter categories to identify the key power brokers, build political coalitions with the early adopters and early majority to secure resources, and keep the late majority/laggard power brokers well informed early in the process to promote buy-in. As the old saying goes, “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.”

Mistake #3: Underestimate the power of a change agent

While understanding the stages of change and adopter categories is helpful, another key variable in the change process is the person leading the change effort: the change agent. This person is responsible for communicating the innovation to all constituent groups. The change agent should be a professional who influences the change decision and guides the organization in a direction desirable by the group or person initiating the change. Change agents achieve more success if they cooperate with opinion leaders, have interpersonal relationships with those affected by the change and are perceived as “client-oriented” (e.g., they want what’s best for the patient). The change agent must be able to diagnose the problem with the status quo, help develop a vision of the preferred reality, cultivate tension between “what is” and “what could be,” translate the organization’s intent into action and stabilize the change. Eventually, the change agent must also help the organization transition away from reliance on the change agent to institutionalization of the innovation.

The ultimate goal of the change agent is to implement the innovation to the point where no one can come into the organization and undo the changes made. Looking back, our diabetes working group was vaguely intended to fulfill the change agent role; however, we did not have training in the area, nor did we have the authority to redistribute resources within the organization to meet the perceived resource needs of the individuals working in the clinic.

Lessons learned

In sum, I can look back at my experience working on the diabetes team and regret that I didn’t know then what I know now about change management. Or I can use the experience positively to pass on the lessons learned and help others who will guide change in their organizations. I won’t have to wait long to try these principles myself. Work starts soon on implementing an uncomplicated pregnancy guideline, and guess who the physician champion is?