Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(5):523-532

Related editorial: Long COVID in Children: What Do We Know?

Patient information: See related handout on long COVID, written by the authors of this article.

Related Letter to the Editor: Acupuncture for the Adjunct Treatment of Long COVID

Author disclosure: Dr. Cheng owns a consulting firm that has contracted with MedIQ, a CME company, for an educational program on “Managing COVID-19–related Care Disruptions.” Drs. Herman and Shih have no relevant financial relationships.

Postacute sequelae of COVID-19, also known as long COVID, affects approximately 10% to 30% of the hundreds of millions of people who have had acute COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines long COVID as the presence of new, returning, or ongoing symptoms associated with acute COVID-19 that persist beyond 28 days. The diagnosis of long COVID can be based on a previous clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 and does not require a prior positive polymerase chain reaction or antigen test result to confirm infection. Patients with long COVID report a broad range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, anosmia, chest pain, cognitive impairment (brain fog), dizziness, dyspnea, fatigue, headache, insomnia, mood changes, palpitations, paresthesias, and postexertional malaise. The presentation is variable, and symptoms can fluctuate or persist and relapse and remit. The diagnostic approach is to differentiate long COVID from acute sequelae of COVID-19, previous comorbidities, unmasking of preexisting health conditions, reinfections, new acute concerns, and complications of prolonged illness, hospitalization, or isolation. Many presenting symptoms of long COVID are commonly seen in a primary care practice, and management can be improved by using established treatment paradigms and supportive care. Although several medications have been suggested for the treatment of fatigue related to long COVID, the evidence for their use is currently lacking. Holistic treatment strategies for long COVID include discussion of pacing and energy conservation; individualized, symptom-guided, phased return to activity programs; maintaining adequate hydration and a healthy diet; and treatment of underlying medical conditions.

This article summarizes the best available evidence for the diagnosis and management of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), also called long COVID, in adults. Proposed etiologies for long COVID include residual damage from acute infection, ongoing viral activity within an intrahost viral reservoir, complications from a hyperinflammatory state, immune dysfunction, and unmasking of preexisting health conditions.1,2

Epidemiology

Data show that long COVID affects approximately 10% to 30% of the hundreds of millions of people who have had acute COVID-19.3,4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 19% of adults who had COVID-19 in the past are still experiencing symptoms.5

Illness from COVID-19 has immediate and long-term consequences that can be conceptualized in three phases. Patients do not routinely develop all three.7

○ Phase 1. An acute illness with varying degrees of severity caused by viral replication and initial immune response lasts days to weeks. Asymptomatic patients can also progress to later phases of the illness.7

○ Phase 2. A rare hyperinflammatory illness known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome may occur two to five weeks after onset of the infection.7–10 Multisystem inflammatory syndrome can affect children and adults and is caused by a dysregulated immune response with signs and symptoms similar to Kawasaki disease.7,8

○ Phase 3. Long COVID may develop and can last for months.1–4

A 2022 study identified type 2 diabetes mellitus, SARS-CoV-2 viremia, Epstein-Barr virus viremia, and specific autoantibodies as risk factors for long COVID.11 Additional risk factors suggested by other studies include age older than 50 years, female sex, more severe acute infection, more than five symptoms in the first week of acute infection, immunosuppressive conditions, underlying health conditions (e.g., hypertension, obesity, psychiatric condition), and partial or no vaccination.12–17

In a large community-based sample, the risk of long COVID in fully vaccinated individuals with breakthrough COVID-19 is less than in partially or unvaccinated individuals.14,18

Patients with long COVID report decreased quality of life on standardized testing.17

Diagnosis

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines long COVID as the presence of new, returning, or ongoing symptoms associated with acute COVID-19 that persist beyond 28 days,18 whereas the World Health Organization defines long COVID as symptoms that last for at least two months.19

The diagnosis of long COVID can be based on a prior clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 with ongoing symptoms. A prior positive polymerase chain reaction or antigen test result to confirm SARS-CoV-2 infection is not required.1 People with COVID-19 may have been asymptomatic or may not have had access to testing, and 10% to 20% do not produce detectable antibodies.1,20,21

The differential diagnosis includes acute sequelae of COVID-19, previous comorbidities, unmasking of preexisting health conditions, reinfection, new acute concerns, and complications of prolonged illness, hospitalization, or isolation.1,15,22

Review of the patient’s medical history should assess for conditions that could impact severity of COVID-19, including asthma, chronic fatigue, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, heart conditions, pulmonary disease, mood disorders, and trauma.1

Physicians should advise patients that long COVID is not fully understood and be sensitive to patient concerns that symptoms could be misattributed to psychiatric causes.1

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Patients with long COVID report a broad range of symptoms, most of which are common presentations in primary care.1,23,24

Presentation is variable, and symptoms can fluctuate or persist and relapse and remit.17,20,22,23

Common symptoms include abdominal pain, anosmia, chest pain, cognitive impairment (brain fog), dyspnea, fatigue, headache, insomnia, dizziness, mood changes, palpitations, paresthesias, and postexertional malaise (Table 117,25–27). The severity of these symptoms may not be consistent with objective findings.1

A comprehensive review of symptom prevalence and trajectory found that in patients who recovered within 90 days, symptoms peaked during the second week. In patients who did not recover before 90 days, symptoms peaked at two months.23

The most common symptoms after six months are fatigue, postexertional malaise, and cognitive dysfunction.23

A survey showed that 85.9% of patients with symptoms of long COVID lasting for more than six months experienced relapses, triggered mainly by physical activity, stress, exercise, or mental activity.23

Postexertional malaise, a hallmark of long COVID, is a disabling, often delayed exhaustion disproportionate to the effort exerted. It is characterized by improvement followed by severe exhaustion and worsening of symptoms requiring several days or weeks of recovery.1,20,28 Similar to other relapsing symptoms, postexertional malaise can be triggered by routine physical activities (e.g., bathing), cognitive activities, and emotional stress.1,20,23,28 The onset of symptoms is often delayed (12 to 72 hours after activity) with unpredictable severity.1,28 Postexertional malaise is distinct from fatigue, which is a feeling of weariness, tiredness, or lack of energy.20

The fatigue experienced in long COVID is often multifactorial and may appear similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue syndrome).20 Myalgic encephalomyelitis is a complex, severe, multisystem syndrome characterized by postexertional malaise that often follows a viral illness.20,28,29 Although patients with long COVID can meet criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis, more data are needed to better understand if fatigue related to long COVID represents a distinct process or is a manifestation of myalgic encephalomyelitis.20

Autonomic dysfunction (dysautonomia) such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) commonly occurs in long COVID and may include abdominal pain, bloating, blurry or tunnel vision, constipation or loose stools, dizziness, fatigue, labile blood pressures, light-headedness, orthostatic intolerance, palpitations, peripheral vasoconstriction, nausea, night sweats, tachycardia, and temperature intolerance.2,30,31 See Table 2 for diagnostic criteria of POTS.32

| Cardiac Chest pain (5% to 16%) Palpitations (5% to 14%) Hypertension (1%) Dermatologic Alopecia (7% to 25%) Flushing (5%) Rash, such as urticaria or livedo reticularis (3%) Ear, nose, and throat Ageusia/parageusia (4% to 23%) Anosmia/parosmia (6% to 21%) Voice changes (8%) Nasal congestion (5%) Throat pain (2% to 5%) | Gastrointestinal Appetite changes (6% to 17%) Nausea/vomiting (6% to 8%) Diarrhea (4% to 8%) Abdominal pain (2% to 6%) Neurologic Difficulty concentrating (18% to 27%) Insomnia/sleep disorders (11% to 27%) Cognitive impairments (17% to 26%) Memory deficits (16% to 19%) Headaches (5% to 12%) Dizziness (3% to 4%) Paresthesias, including focal, diffuse, and changing locations (9%) Vision changes (5%) | Psychiatric Anxiety (13% to 30%) Depression (8% to 23%) Posttraumatic stress disorder (1% to 13%) Dyspnea (18% to 30%) Cough, new or progressive (5% to 15%) Systemic Fatigue (28% to 58%) Night sweats (17% to 24%) Weight loss (12% to 21%) Mobility decline (14% to 20%) Decreased exercise tolerance (15%) Fever (0.3% to 11%) Rheumatologic Arthralgia (9% to 14%) Myalgia (8% to 13%) |

| Heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute or more, or more than 120 beats per minute within the first 10 minutes of standing, in the absence of orthostatic hypotension; in children and adolescents, the standard is a heart rate increase of 40 beats per minute or more |

| Symptoms of orthostatic intolerance |

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

A basic laboratory panel, including complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ferritin, thyroid stimulating hormone, vitamin D, and vitamin B12, should be obtained to identify treatable conditions.1

Further diagnostic testing is guided by specific history and physical examination findings, persistence and severity of symptoms, the possibility of other post-COVID complications, and a shared understanding of the risks and benefits.1,3,22,24,33

Targeted evaluation and management for symptom complexes associated with long COVID are summarized in Table 3.1,3,20,24,31,34–42

Although laboratory and diagnostic test results are commonly normal in patients with long COVID, clinicians should not disregard the impact of symptoms on a patient’s daily functioning, quality of life, and ability to return to school or work.1,17

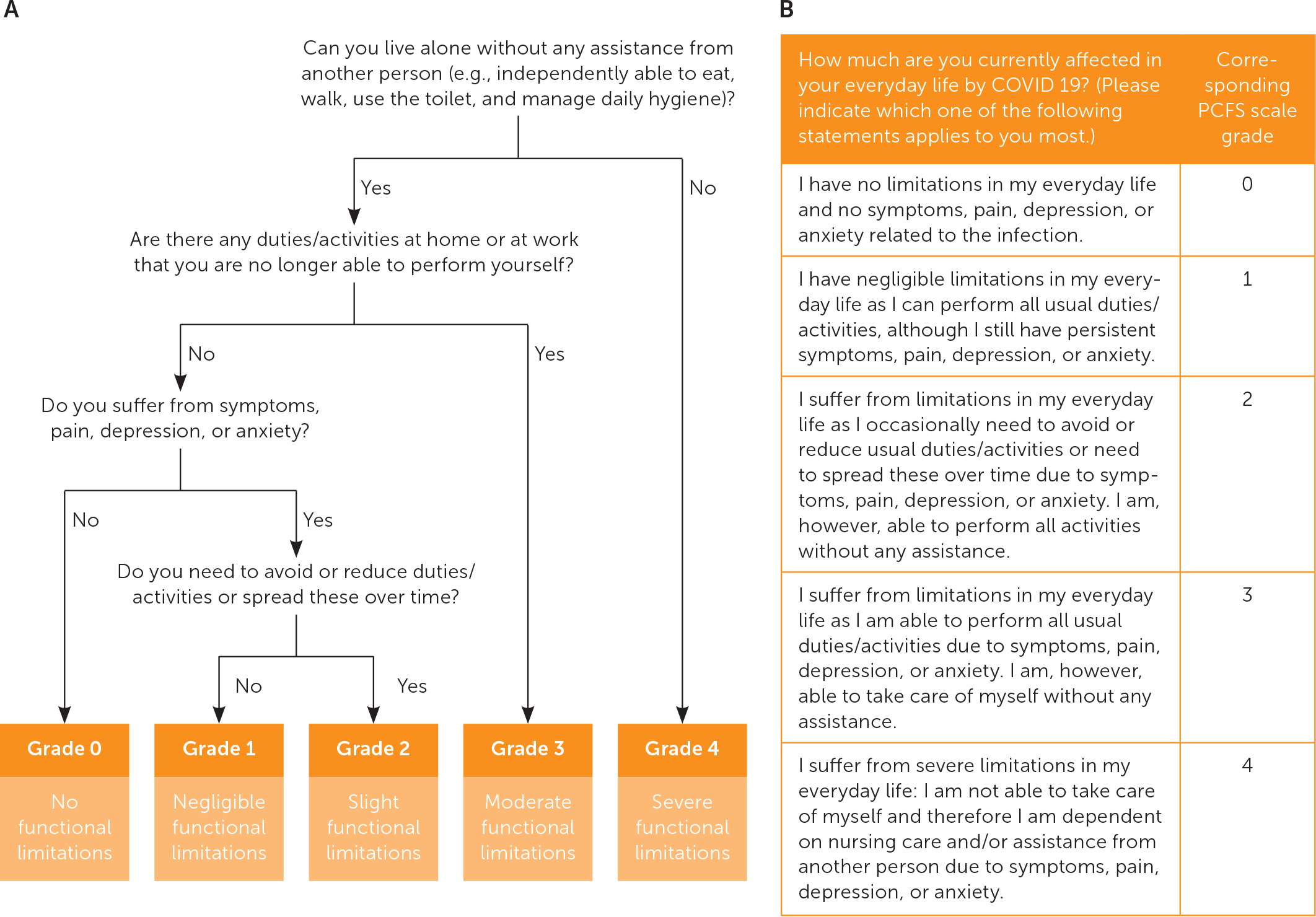

Clinical assessment tools and survey instruments for long COVID are listed in eTable A. These tools can be considered to evaluate a patient’s functional ability and monitor symptoms in various domains. Figure 1 is an algorithm for determining a patient’s self-reported functional status.43

| Symptom complex | Differential diagnosis | Initial evaluation* | Treatment† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anosmia/parosmia24 | Allergies, postnasal drip | Consider allergy testing | Smell training (see patient handout with the online version of this article) Consider intranasal steroids |

| Autonomic dysfunction/dysautonomia24,31,34–37 | POTS, deconditioning, dehydration, mast cell activation syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, paraneoplastic syndrome, arrhythmia due to cardiac or pulmonary disease, thyrotoxicosis, celiac disease | CBC, complete metabolic panel, thyroid stimulating hormone Orthostatic vital signs (Table 2), ECG, autonomic reflex testing Consider vitamin B12, celiac panel, ambulatory heart rate monitoring, echocardiography | Fluid and salt repletion, compression garments Sleeping in the head-up position Isometric exercises Small, more frequent meals Physical reconditioning program (when stable) Avoidance of triggers Medications: propranolol, fludrocortisone, pyridostigmine, midodrine |

| Brain fog (e.g., difficulty concentrating, memory deficits, cognitive impairment)38 | Stroke, progressive neurologic illness (e.g., multiple sclerosis, dementia), sleep disorder, encephalopathy, mood disorders, fatigue, traumatic brain injury, endocrine and autoimmune disorders | Montreal Cognitive Assessment CBC, vitamin B12, vitamin D, thiamine, folate, homocysteine, magnesium, complete metabolic panel, liver function tests, thyroid function tests Consider neuropsychological testing (CT or magnetic resonance imaging of the head) | Referral to specialist with expertise in formal cognitive assessment and remediation Paced return to activity Polypharmacy reduction Discontinuation of medications that may impact cognition, if possible Sleep hygiene |

| Breathing discomfort1,3,24,39 | Anemia, asthma, heart failure, pneumonia, pulmonary fibrosis, myocarditis, coronary artery disease, venous thromboembolism | Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, STOP-BANG questionnaire for obstructive sleep apnea B-type natriuretic peptide, CBC Chest radiography, ECG, functional capacity testing, pulmonary function tests Consider d-dimer, ferritin, chest CT, echocardiography, home pulse oximetry | Breathing exercises Paced return to activity Pulmonary rehabilitation |

| Chronic fatigue (e.g., myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome)20,24 | Autoimmune, cardiovascular, endocrine, mood, pulmonary, and sleep disorders | Fatigue severity scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, STOP-BANG CBC, complete metabolic panel, thyroid stimulating hormone Functional capacity testing Consider antinuclear antibody, B-type natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein, d-dimer, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cortisol, ferritin, chest radiography, ECG, pulmonary function tests, chest CT, echocardiography | Energy conservation strategies Paced return to activity Healthy diet, hydration |

| Mast cell activation syndrome (anxiety, conjunctivitis, hypotension, palpitations, rashes, rhinitis, sore throat, urticaria, and wheezing)37,40–42 | POTS, multisystem inflammatory syndrome, diabetes mellitus, endocrine tumors, porphyria, thyrotoxicosis, parasitic infections, celiac disease, vasculitis | Tryptase (baseline and less than four hours from onset of flare-up), 24-hour urine collection to test for N-methylhistamine and prostaglandin D2 | Medications: cromolyn, H1 and H2 histamine antagonists, mast cell stabilizers |

Treatment

Treatment recommendations for long COVID are based on expert opinion and consensus guidelines in the absence of clinical trials.1,20,22,24,38,44 The goal of treatment is to optimize function and improve quality of life.1

A comprehensive plan of care requires a whole-patient perspective representative of the patient’s presenting symptoms, underlying conditions, psychological well-being, personal and social situations, and treatment goals.1,3

An individualized, symptom-guided, phased return to activity program is recommended for patients with fatigue or postexertional malaise (Table 4).20 This is different from graded exercise therapy, which is controversial in the management of myalgic encephalomyelitis. Before initiating a program, patients should be assessed for fatigue patterns throughout the day and advised to avoid activities that trigger postexertional malaise. The appropriate range of activities used in the program is highly dependent on the patient. Guidelines also recommend assessing a patient’s response to initiating and escalating activities.20

Patients with cognitive impairment as a result of long COVID should be referred to a specialist with expertise in formal cognitive assessment and remediation (e.g., neuropsychologist, speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist).38

Clinicians should address polypharmacy and, if possible, discontinue medications that may impact cognition.38

Patients with ongoing cough and dyspnea may benefit from breathing exercises that focus on optimal body position and posture (see patient handout with the online version of this article), pulmonary rehabilitation for pulmonary disease, and a phased return to activity program.15,22,39

The recommended treatment for dysautonomia (e.g., POTS) includes dietary and behavior modifications such as ensuring fluid and salt repletion; wearing compression garments; performing isometric exercises; eating small, more frequent meals; implementing physical reconditioning programs in nonupright positions (when stable); and avoiding exacerbating factors (e.g., alcohol use, warm environments).30,31,35

For symptoms of dysautonomia that persist despite conservative measures, first-line pharmacologic agents include propranolol, fludrocortisone, pyridostigmine, and midodrine.31,34 Patients with POTS are highly sensitive to the effects of medical management, and the lowest dose should be used first.45

Recommended initial treatments for symptoms suggestive of mast cell activation syndrome (anxiety, conjunctivitis, hypotension, palpitations, rashes, rhinitis, sore throat, urticaria, and wheezing) include H1 and H2 histamine antagonists, cromolyn, and leukotriene inhibitors.40,42

Many presenting symptoms and conditions associated with long COVID are commonly seen in primary care practice and can be managed using established treatment paradigms and supportive care.1,22,24 Examples include renal disease, chronic pain, hyperglycemia, insomnia, mood disorders, paresthesias, pulmonary infections, small fiber neuropathy, and thromboembolism.

Several medications commonly used to treat fatigue in other conditions (e.g., myalgic encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, cancer) have been suggested for the treatment of fatigue related to COVID-19, including modafinil (Provigil), methylphenidate (Ritalin), and amantadine.20,24 However, evidence for this use is insufficient.20

Follow-up visits are patient-specific but can be considered every two to three months.1

Although an in-person visit may have advantages for physiologic evaluation and other assessments, telemedicine approaches with phone calls or virtual visits can be helpful for follow-up and lessen the burden on patients.20,44

| The goal is to restore previous levels of activity and improve quality of life. |

| If the program is advanced too quickly, it can worsen symptoms and trigger postexertional malaise. |

| Patients are directed to perform activities at submaximal levels. |

| Activities are adjusted in response to symptoms that develop during and after activity. |

| Patients are educated on how to recognize perceived exertion and use other metrics such as heart rate or validated exertion scales. |

| Activity recommendations depend on level of symptom severity and progress according to symptom tolerance. |

| Until goals are achieved, patients should not initiate high-intensity aerobic exercises or heavy weight training. |

| An example of program progression could be bedside mobilization, range of motion exercises, tolerated household activities, stretching of extremities, limited community activities, submaximal exercise, and eventual higher-intensity activities. |

| Consider referral to a physiatrist or physical therapist who is knowledgeable in caring for patients with long COVID and can monitor the course of the program. |

LIFESTYLE AND BEHAVIOR INTERVENTIONS

Energy conservation strategies such as the four P’s framework (planning, pacing, prioritizing, positioning) and the stop, rest, pace strategy, and avoiding relapsing triggers may help patients mitigate fatigue.3,15,20,24,28,38

Patients should be supported in maintaining adequate hydration and a healthy diet.1,3,20

Information on peer support resources should be provided (see patient handout with the online version of this article).1

REFERRAL, CONSULTATION, AND HOSPITALIZATION

Structured coordination of care and connection to social services can benefit vulnerable populations with long COVID.20

Primary care clinicians can manage most patients with long COVID, but almost every state has specialized clinics that can be used for more complex cases. Physicians can find post-COVID care centers in their state at https://www.survivorcorps.com/pccc.

Specialty referral should be considered if initial treatment is unsuccessful, for complex or severe presentations, or for new concerning findings on imaging or other studies.3,24,39

Prognosis

Most patients can expect gradual improvement in functional status with a relapsing and remitting course, aided by careful pacing, prioritization, and goal setting.3,24

Although many individuals may experience resolution of some or all symptoms over time, the ultimate long-term prognosis of long COVID is unclear.24,46

Clinicians should set expectations for patients, advising that there are varying outcomes and rates of recovery.1

One study found a progressive decline in the average number of symptoms after seven months; however, 65.2% of patients still had symptoms after six months. Those with continued postexertional malaise experienced a higher number of average symptoms.23

Most individuals with long-term breathing difficulties do not develop permanent or chronic lung injury.15

Most people will gradually recover from cognitive impairment after a severe illness.15

Long COVID is now a recognized disability under the Americans With Disabilities Act, sections 504 and 1557.47

Data Sources: A search of PubMed was completed using the key terms long COVID and post-acute symptoms of COVID-19. The search included government and professional organization websites such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Essential Evidence Plus library was also searched. A reference library was curated by the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine COVID-19 Inquiry Group and through professional collaborative networks. Search dates: August 2021 through August 2022.

The authors thank the Oregon Health and Science University Long COVID-19 Clinical Guidelines Team and the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine COVID-19 Inquiry Group.