Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(5):503-512

Patient information: See related handout on shoulder pain.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Acute shoulder pain lasting less than six months is a common presentation to the primary care office. Shoulder injuries can involve any of the four shoulder joints, rotator cuff, neurovascular structures, clavicle or humerus fractures, and contiguous anatomy. Most acute shoulder injuries are the result of a fall or direct trauma in contact and collision sports. The most common shoulder pathologies seen in primary care are acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joint disease and rotator cuff injury. It is important to conduct a comprehensive history and physical examination to identify the mechanism of injury, localize the injury, and determine if surgical intervention is needed. Most patients with acute shoulder injuries can be treated conservatively using a sling for comfort and participating in a targeted musculoskeletal rehabilitation program. Surgery may be considered for treating middle third clavicle fractures and type III acromioclavicular sprains in active individuals, first-time glenohumeral dislocation in young athletes, and those with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Surgery is indicated for types IV, V, and VI acromioclavicular joint injuries or displaced or unstable proximal humerus fractures. Urgent surgical referral is indicated for posterior sternoclavicular dislocations.

The location of the shoulder and its wide range of motion place it at risk for traumatic and nontraumatic injuries to the bony and soft tissue structures. Clavicle and proximal humerus fractures account for 12% and 4% to 6% of fractures in adults, respectively.1 Shoulder pain is common and affects 5% to 47% of adults each year.2 Acute shoulder pain lasting less than six months is a common presentation to primary care. The initial approach to acute shoulder injuries starts with a comprehensive history to understand the mechanism of injury and a complete shoulder examination to localize the injury.3,4

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Use plain radiography as the recommended initial imaging modality for traumatic shoulder injuries to rule out fracture.10 | C | Consistent evidence from cohort studies |

| Consider surgery in active patients younger than 25 years with anterior shoulder dislocation.23–26 | B | Consistent evidence from cohort studies showing a lower rate of recurrence after surgery |

| Encourage nonoperative treatment of proximal humerus fractures in older patients.36 | B | Consistent evidence from cohort studies showing fewer complications and better or equivalent outcomes compared with surgical management |

| Use ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging to detect complete rotator cuff tears. They have similar sensitivity and specificity.37,42,45–47 | C | Limited evidence from randomized controlled trials showing skilled ultrasonography is equivalent to magnetic resonance imaging in detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears but less accurate at identifying damage to deep structures; magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography are less sensitive for partial tears |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Consider evaluating rotator cuff tears with ultrasonography before ordering magnetic resonance imaging. | American Medical Society for Sports Medicine |

| Avoid routine use of opioids for treatment of knee or hip osteoarthritis, low back pain, or rotator cuff injury. | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons |

Initial Evaluation

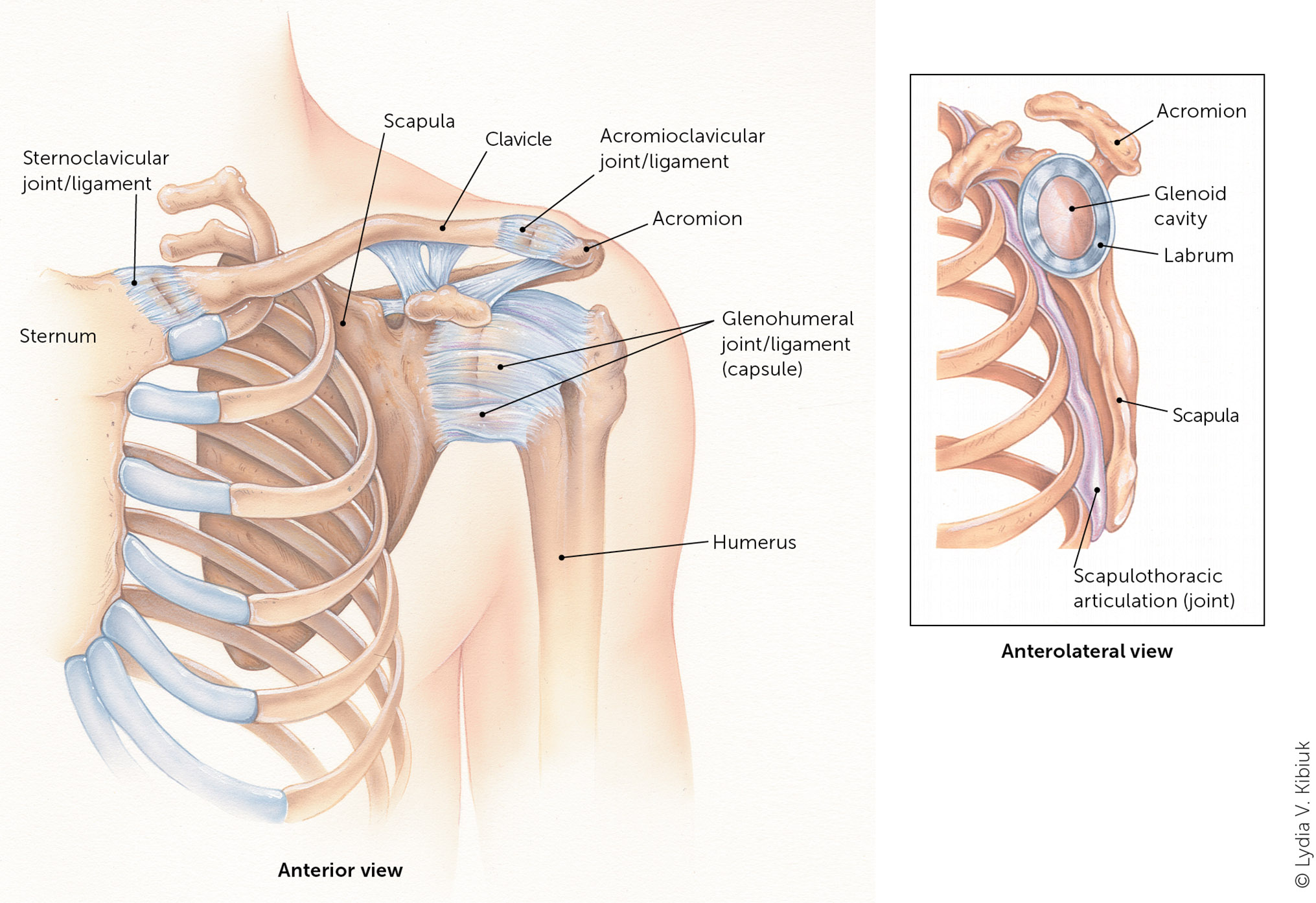

The initial evaluation should include a physical examination of all anatomic aspects of the injured shoulder, including the humerus, clavicle, scapula, soft tissue, and neurovascular structures, and comparison with the uninjured side.5–7 Figure 1 shows the anatomy of the shoulder.8 The acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, and glenohumeral joints articulate with the bony skeleton. The scapulothoracic joint does not articulate directly with the axial skeleton. Shoulder injuries may occur to the rotator cuff, neurovascular structures, and contiguous anatomy, including the glenoid labrum, biceps tendon, and referred pain to the shoulder from the cervical spine. Most of these injuries do not require surgery and can be managed by the family physician. Analgesics, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, may be indicated for initial pain management. Table 1 summarizes the evaluation and management of several acute shoulder injuries.9 After history and physical assessment, plain radiography is the initial imaging modality endorsed by the American College of Radiology.10 Management includes assessing and stabilizing the injury, providing symptom control, allowing time for recovery, and restoring range of motion and function.

| Evaluation and management | Common acute shoulder injuries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acromioclavicular joint injury | Glenohumeral joint injury | Clavicle facture | Proximal humerus fracture | Rotator cuff injury | |

| Diagnostic imaging | Anteroposterior, axillary, and Zanca views | Anteroposterior, scapular Y, and axillary or Velpeau views | Anteroposterior and serendipity views | Anteroposterior glenoid, scapular Y, and axillary views | Consider ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging |

| Indications for referral | Rockwood types IV to VI; consider referral for Rockwood type III | Recurrent dislocation; young athletes with their first dislocation at younger than 25 years | Displaced or group II fractures; immediate referral for posterior dislocation | Displaced and unstable fractures; consider for active patients | Acute injuries, especially full-thickness tears |

| Initial management | Sling for comfort | Sling for two to four weeks | Sling for two to six weeks | Sling for six to eight weeks | Physical therapy for six weeks |

Shoulder Joint Injuries

ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT

The acromioclavicular joint connects the axial skeleton to the shoulder girdle. It provides rotational and translational movement and is important for static and dynamic stabilization of the shoulder. The acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligament complexes and the joint capsule are static stabilizers that aid in scapular protraction and retraction.11

Acromioclavicular joint injuries are common in men 20 to 49 years of age and are seen in contact sports such as football and hockey.12 Mechanisms of injury include direct contact to the lateral shoulder, a fall onto an outstretched arm, or fall onto the acromion with the arm in an adducted position, which may be seen in cycling.

The Rockwood classification for acromioclavicular joint injuries correlates with the amount and direction of displacement of the acromioclavicular joint shown on radiography with anteroposterior, axillary, and Zanca views and comparing the injured side with the unaffected side. The six types of acromioclavicular joint injuries are noted in Table 2.8,13 Types I and II are treated nonoperatively. Treatment is controversial for type III injuries. Studies show that up to 80% of patients will have a good outcome without surgery; therefore, for most patients, surgical intervention should be considered only after conservative treatment has failed.14,15 Surgical treatment should be considered immediately for type III injuries in physically active patients, such as athletes, military personnel, or manual laborers.13 Types IV through VI require surgical intervention.

| Rockwood classification | Characteristics | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Partial tear of acromioclavicular ligament without radiographic instability | Nonoperative, sling for comfort | |

| Type II | Complete tear of acromioclavicular ligament and partial tear of coracoclavicular ligament | Nonoperative, sling for comfort | |

| Type III | Compete tear of both acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments; vertical and horizontal instability on clinical examination and radiography shows increased coracoclavicular distance of up to 100% of contralateral acromioclavicular joint | Nonoperative, sling for comfort or consider surgical intervention | |

| Type IV | Complete tear of acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments; distal clavicle posterior displacement with buttonholing through the trapezius | Surgical intervention | |

| Type V | Complete tear of acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments; radiography shows 100% to 300% increase of coracoclavicular distance | Surgical intervention | |

| Type VI | Complete tear of acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments; distal clavicle inferior displacement under the acromion or coracoid; possible damage to the deltotrapezial fascia | Surgical intervention | |

STERNOCLAVICULAR JOINT

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocation can occur when the arm is pulled posteriorly with force. Treatment is nonoperative but may lead to residual prominence of the sternoclavicular joint. Posterior sternoclavicular joint dislocation occurs from a compressive anterior force, usually the result of major trauma to the upper, anterior chest. Posterior sternoclavicular joint dislocation presents with pain, shortness of breath, and hoarseness and can cause compression of the great vessels, trachea, and esophagus. It is considered a medical emergency that requires immediate confirmation with computed tomography (CT) and surgical intervention for joint stabilization.

GLENOHUMERAL JOINT

The glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated joint and usually dislocates anteriorly.16 Glenohumeral joint dislocations are usually caused by trauma, falls, and contact and collision sports and may be associated with glenoid labral tears, cartilage damage, or bony injuries such as bony Bankart (glenoid cavity of anterior/inferior scapula) or Hill-Sachs (proximal humeral head) deformity. Posterior glenohumeral joint dislocation is less common but can occur when a posterior-directed force is applied to a flexed shoulder as seen in seizure and electric shock. The subtle presentation can be easily missed.17 Radiography with an axillary or Velpeau orthogonal view should be obtained to avoid missed injuries in the setting of instability.18

Anterior glenohumeral joint dislocations occur when an arm is forced into abduction, external rotation, and hyper-extension. Immediate reduction can often be performed without analgesia. If needed, intra-articular lidocaine is as effective as systemic analgesia or sedation for reduction.19 Multiple methods have been shown to successfully reduce the anteriorly dislocated shoulder (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HtOnreM7heg), but scapular manipulation has been shown to be superior when systematically compared with other techniques.20

Pre- and postreduction axillary nerve function should be assessed by testing sensation to the lateral shoulder and deltoid muscle strength. Plain radiography should be obtained to confirm positioning. Treatment includes the use of a sling for two to four weeks with a graduated rehabilitation of passive and active range of motion. Athletes can return to play when they are pain free with symmetrical shoulder range of motion and able to perform sport-specific motions. This may be as early as two to three weeks after injury.21

SCAPULOTHORACIC JOINT

The scapulothoracic joint includes the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints, scapulothoracic junction, anterior wall of the scapula, and superolateral surface of the thoracic wall. The scapulothoracic joint is responsible for most of the shoulder's large range of motion.5 Scapulothoracic joint injury is uncommon, but scapular fractures can occur with severe trauma.27 Rarely, patients with osteoporosis can sustain a fracture without trauma. Scapular fractures are treated nonoperatively (if the fracture does not include the glenoid), with a sling or shoulder immobilizer for two to four weeks until the acute pain resolves. CT may be needed to diagnose these types of fractures due to difficulty visualizing them with radiography.

Clavicle Fracture

Approximately 2% to 5% of clavicle fractures occur in adults and males younger than 30 years, and people older than 70 years are at highest risk.28 The Allman classification of clavicle fractures divides the clavicle into three groups based on anatomic fracture location (listed in decreasing order of fracture incidence): group I, middle third; group II, lateral third; and group III, medial third of the clavicle.29,30 Most nondisplaced clavicle fractures are treated with a sling for comfort for two to six weeks.31 Although surgery may be considered for middle third clavicle fractures, nonoperative vs. operative management for displaced middle third fractures is controversial.32–34 A previous American Family Physician article provides more information on management of clavicle fractures (https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2008/0101/p65.html).

Humeral Head Fracture

Proximal humerus fractures account for approximately 6% of adult fractures, and they increase in incidence with age and are usually sustained in a fall from standing height.27 Treatment is determined based on the location and degree of displacement of the fracture segments using the Neer classification35 (https://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/images/uploaded/neers_fracture_class.jpg). It is estimated that 85% of all proximal humerus fractures have minimal displacement (i.e., less than 1 cm) and minimal angulation (i.e., less than 45 degrees). These fractures are treated nonoperatively with immobilization or closed reduction followed by physical therapy for recovery of function. Surgical intervention should be considered for displaced or unstable humerus fractures. Consistent evidence from cohort studies shows fewer complications and better or equivalent outcomes with nonoperative vs. surgical management in older patients.36

Rotator Cuff Pathology

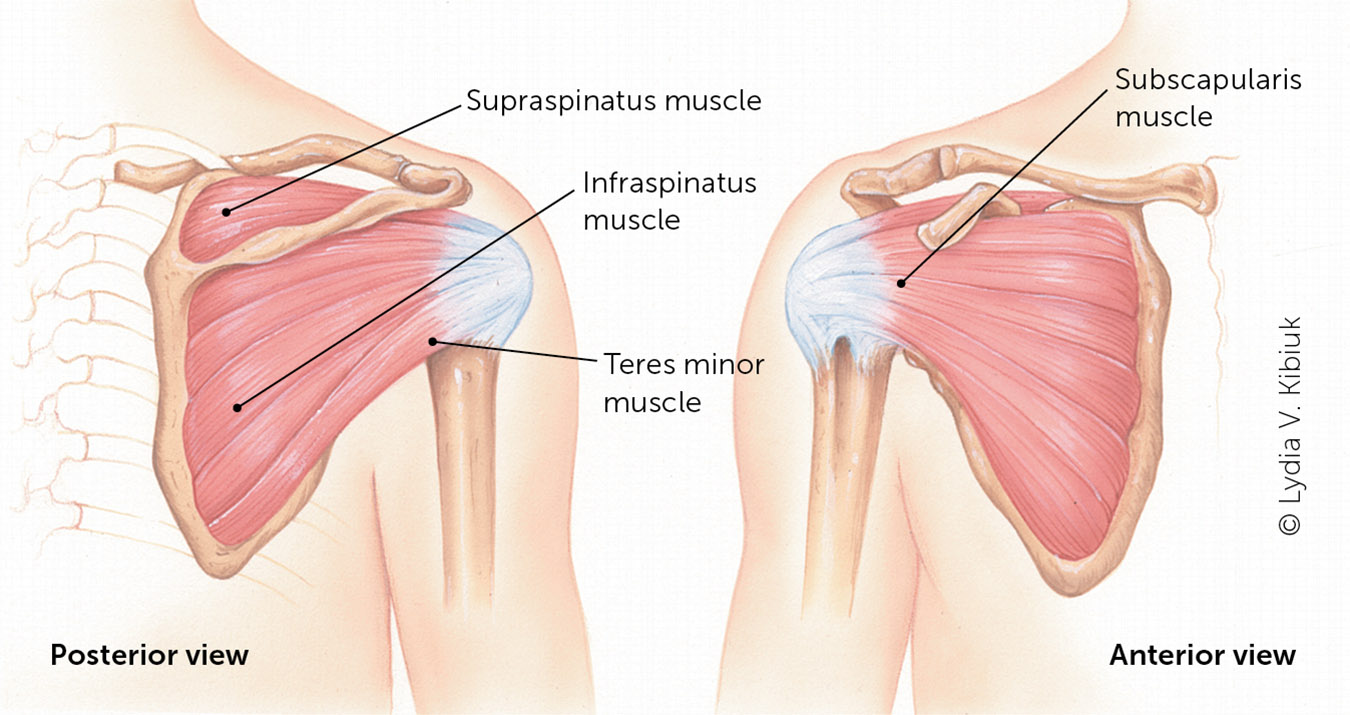

Rotator cuff injury and tendinopathy account for 65% of all shoulder pain visits.37 The rotator cuff is the major stabilizer of the shoulder and includes the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscles. Because of its wide range of motion, it is prone to injury from repetitive use, trauma, fracture, or dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. Subacromial bursitis and impingement syndrome are common sources of anterolateral shoulder pain with shoulder abduction.

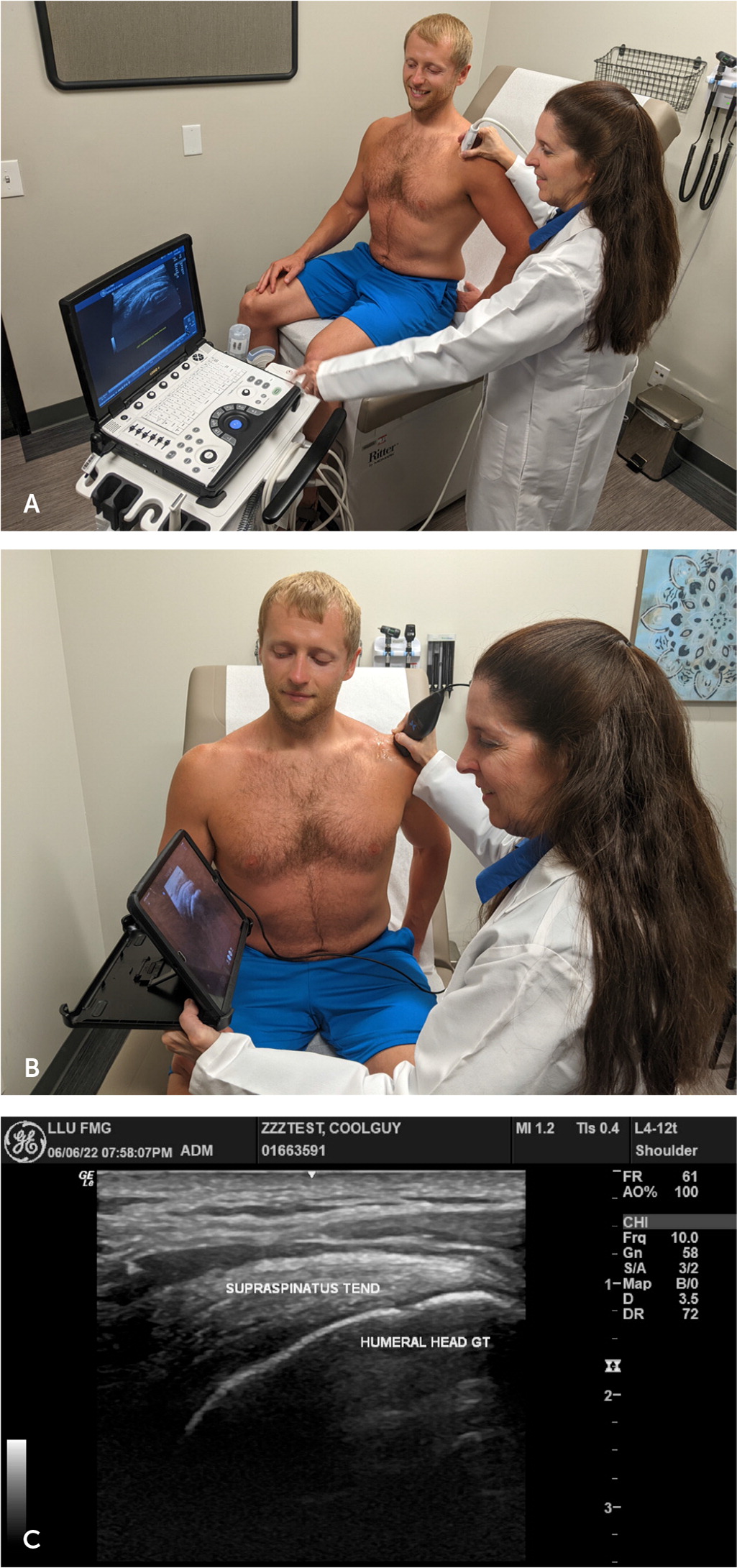

CT, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to assess the rotator cuff.9 CT arthrography is the most sensitive and specific test for evaluating rotator cuff pathology; however, it is rarely used because it is invasive and involves radiation exposure.3,38,39,41–44 Ultrasonography has high sensitivity and specificity for identifying full-thickness tears, is comparable to MRI in the hands of a skilled operator,45–47 and has the advantage of dynamic imaging compared with CT or MRI.10,37,42,47 Formal or point-of-care ultrasonography can be performed to assess the rotator cuff (Figure 4). The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography and MRI are lower with partial rotator cuff tears compared with complete tears.41–44,48 However, MRI is more sensitive (93%) than ultrasonography (52%) in detecting partial tears, if imaging is indicated.49

Young, active patients with acute full-thickness tears have improved outcomes with surgical intervention compared with conservative management.40,45,46 Nonoperative conservative management for partial tears includes analgesia, physical therapy, and shoulder injections.45,50 Corticosteroid injections, prolotherapy, platelet-rich plasma, biologics, and ultrasound-guided barbotage (i.e., needling and lavage) have mixed results.45,46,50 Older patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears may have good clinical outcomes with proper rehabilitation, including anterior deltoid reeducation.51

Neurovascular Pathology

BRACHIAL PLEXUS INJURY

Brachial plexus injuries are a type of cervical neurapraxia that can occur when there is forced compression or stretching of the cervical spine, such as the head rotated and neck side-bent during a football tackle, causing what is commonly known as a burner or stinger. Patients usually present with the affected arm held close to the body or trying to shake out the burning or stinging pain that radiates from the shoulder down the arm in one or more of the C5 through C8 nerve distributions.44,45,52 These symptoms usually resolve spontaneously within a few minutes, with the individual regaining full strength and range of motion. If symptoms persist longer than 24 hours, further cervical assessment is indicated.52

Injuries can occur with traction and compression of the brachial plexus and are seen in hikers and military personnel carrying a heavy pack for hours (backpacker palsy) and pitchers. Symptoms vary based on the location of the brachial plexus injury but are most often associated with motor weakness of the shoulder or upper arm and sometimes with arm or hand paresthesia. Symptoms typically resolve within one year.53 Activity modification and physical therapy can help prevent further compression and accelerate return to function.

Other Pathology

EFFORT THROMBOSIS

Vascular events can present as acute shoulder injuries. Primary effort thrombosis is a deep venous thrombosis of the upper extremity, and the incidence is 1 to 2 in 100,000 people per year. It is usually seen in healthy, young male athletes, such as weightlifters or swimmers, or laborers.54 This injury may present with acute axillary or upper arm swelling or pain after a sudden or recurrent upper arm activity that compromises venous outflow and causes a bluish hue to the arm.55 Diagnosis of effort thrombosis is confirmed with Doppler ultrasonography or venography and necessitates urgent referral for vascular management with catheter-directed thrombolysis or surgery.56

GLENOID LABRUM

Acute labral tears, such as superior labral anterior to posterior lesions, can occur during a fall onto an outstretched arm or with high velocity overhead activities, such as throwing. The O'Brien active compression test (pain against resistance with the shoulder forward flexed 90 degrees, arm adducted 15 degrees, and internally rotated with forearm pronation/thumb down; Figure 5) has a high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing superior labral anterior to posterior lesions.6 Treatment for acute labral tears is physical therapy.

BICEPS TENDON

The long head of the biceps tendon is contiguous to the superior aspect of the glenoid labrum, and injuries commonly occur with tears to the superior labrum or the supraspinatus tendon. Up to 76% of rotator cuff tears are associated with long head of the biceps tendinitis or rupture of the biceps tendon.57 Most long head of the biceps tendon tears and biceps tendinopathy are treated nonoperatively with physical therapy and activity modification. Tendinopathy treatment can also include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections into the biceps tendon sheath. In cases of severe refractory pain, biceps tenodesis or tenotomy may be considered.58

CERVICAL SPINE

Cervical radiculopathy can refer pain to the shoulder. It is typically from C5, C6, or myelopathy from disk or joint disease or fracture. A complete cervical examination should be included in acute shoulder injury evaluations.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Monica, et al.,9 and Quillen, et al.8

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key search terms shoulder injuries, biceps tendon, clavicle fractures, rotator cuff injuries, shoulder imaging, epidemiology of shoulder injuries, and brachial plexopathy. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, randomized clinical trials, and reviews. Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, and DynaMed were also searched. Search dates: May 2022 and March 2023.